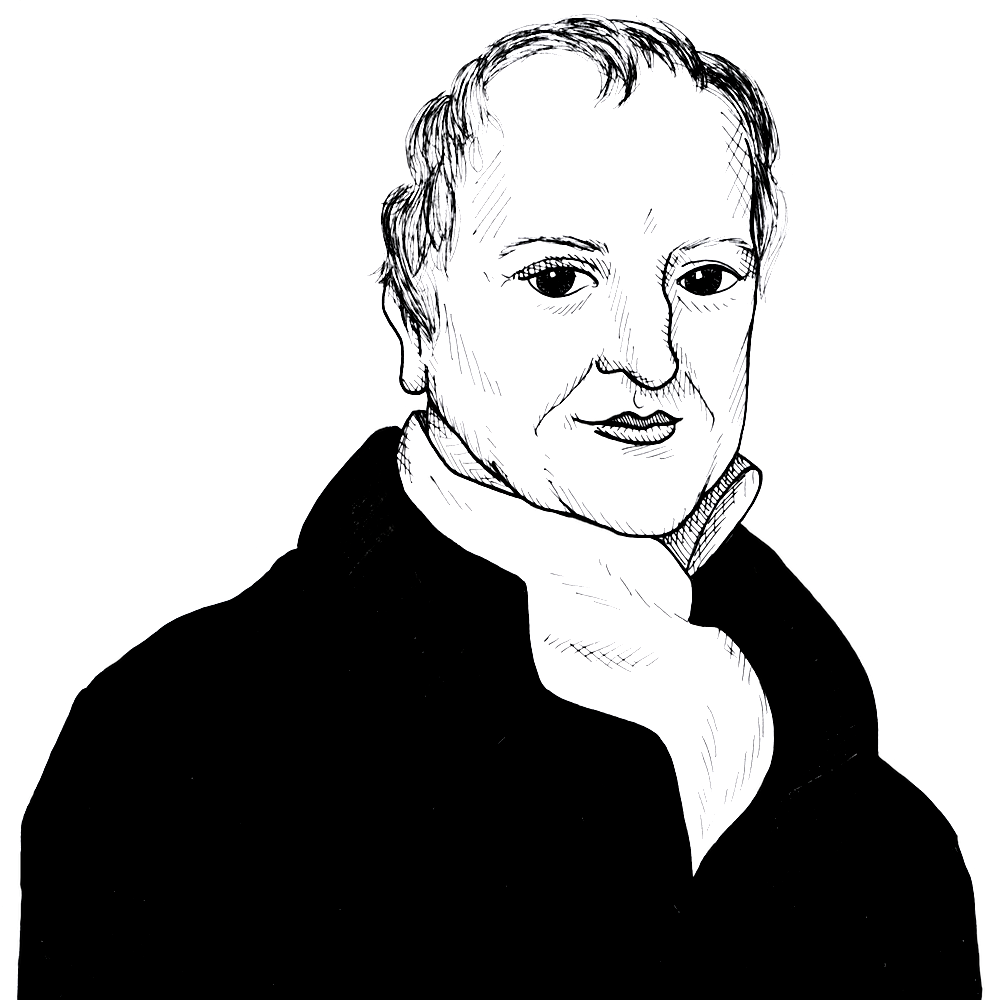

David Ricardo on Wages and the Deflation of Currency

Found in: The Works of David Ricardo (McCulloch ed. 1846, 1888)

Two years after their victory at Waterloo, when David Ricardo wrote “The Iron Laws of Wages,” in 1817, the British had already won the Napoleonic Wars, but the suspension decreed in 1794 of redemption in gold of the banknotes issued in profusion by the Bank of England (BoE) to finance that war was still four years in the future.

There were much more paper money in circulation than what would be possible to redeem with the paltry reserves of gold in the coffers of all the banks in the empire if the pre-war parity were to be respected.

Because the honor of the Crown demanded the public debt to be repaid at the parity in which it was contracted, a long and painful deflationary process was initiated as the troops were demobilized, military costs slashed, and gold gradually accumulated again in the vaults of the BoE.

Therefore, nominal wages needed to be reduced substantially if the deflation of the currency was to be successful and redemption at the pre-war parity resumed.

Economics

These, then, are the laws by which wages are regulated, and by which the happiness of far the greatest part of every community is governed. Like all other contracts, wages should be left to the fair and free competition of the market, and should never be controlled by the interference of the legislature. (FROM CHAPTER V.: ON WAGES)