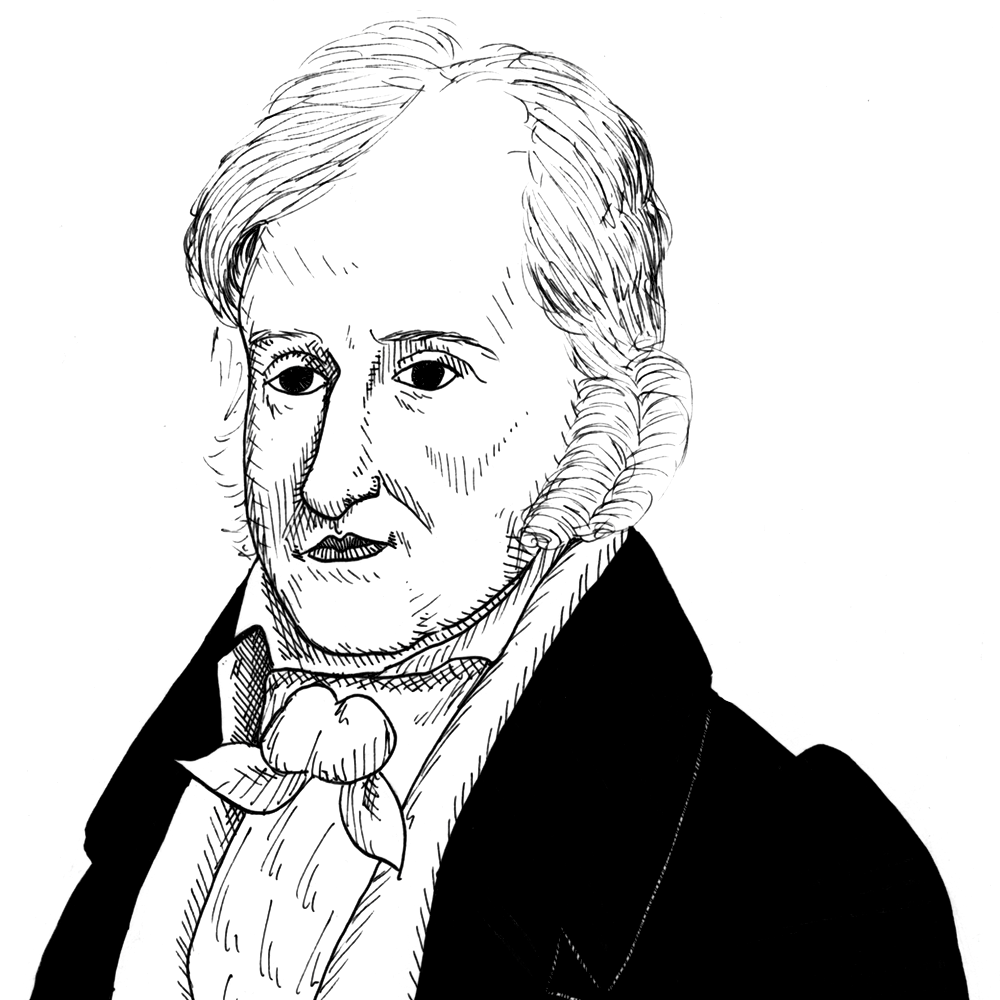

Benjamin Constant distinguished between the Liberty of the Ancients (“the complete subjection of the individual to the authority of the community”) and that of the Moderns (“where individual rights and commerce are respected”) (1816)

Found in: The Liberty of Ancients Compared with that of Moderns (1819)

In this section of his essay Constant argues that the right to engage in commerce and the protection of property rights which makes this possible is one of the key factors which distinguished modern liberty from ancient liberty:

Politics & Liberty

The effects of commerce extend even further: not only does it emancipate individuals, but, by creating credit, it places authority itself in a position of dependence. Money, says a French writer, ‘is the most dangerous weapon of despotism; yet it is at the same time its most powerful restraint; credit is subject to opinion; force is useless; money hides itself or flees; all the operations of the state are suspended’. Credit did not have the same influence amongst the ancients; their governments were stronger than individuals, while in our time individuals are stronger than the political powers. Wealth is a power which is more readily available in all circumstances, more readily applicable to all interests, and consequently more real and better obeyed. Power threatens; wealth rewards: one eludes power by deceiving it; to obtain the favors of wealth one must serve it: the latter is therefore bound to win.