Adam Smith on Good Wine and Free Trade

Found in: An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Cannan ed.), vol. 2

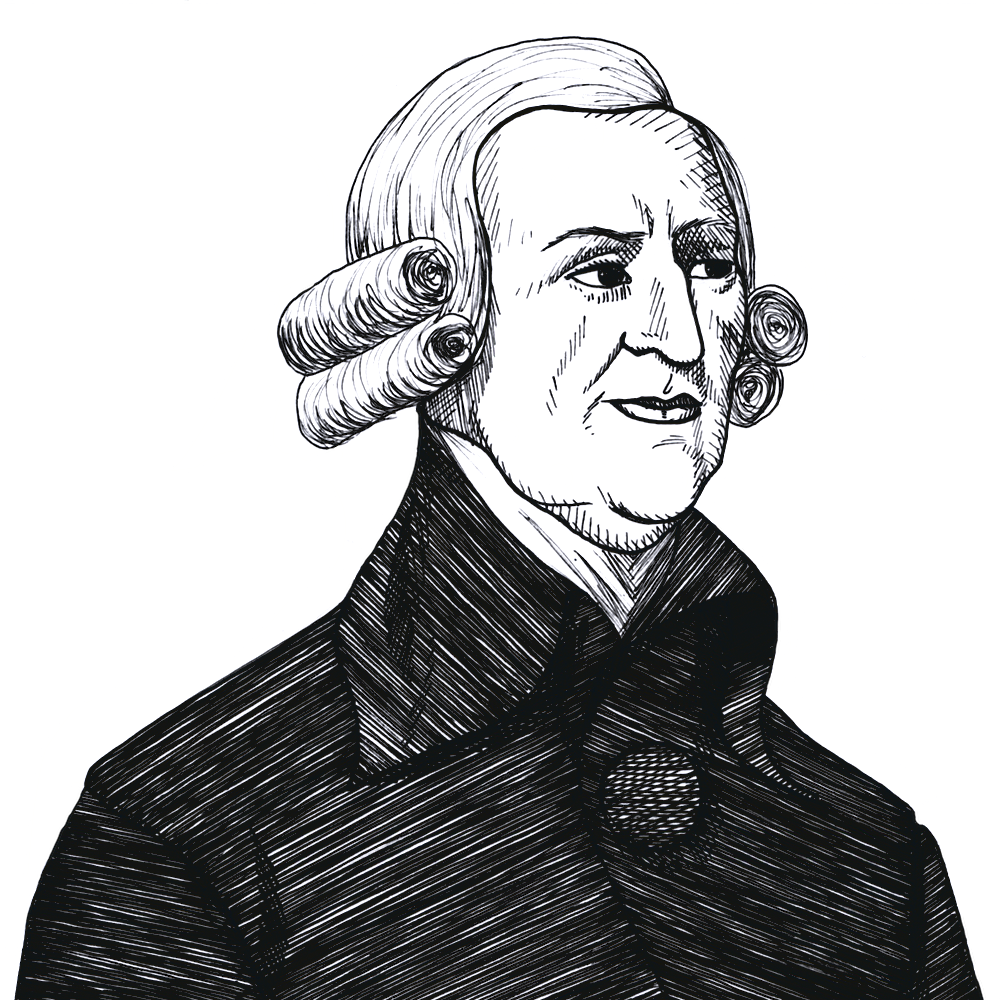

The Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith (1723–1790) was the author of two books, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776).

He is best known today for his economic arguments, especially arguments in favour of free trade between nations. In Book IV, Chapter 2 of Wealth of Nations, Smith writes:

Economics

By means of glasses, hotbeds, and hotwalls, very good grapes can be raised in Scotland, and very good wine too can be made of them at about thirty times the expense for which at least equally good can be brought from foreign countries. Would it be a reasonable law to prohibit the importation of all foreign wines, merely to encourage the making of claret and burgundy in Scotland?