Works of Lysander Spooner vol. 4

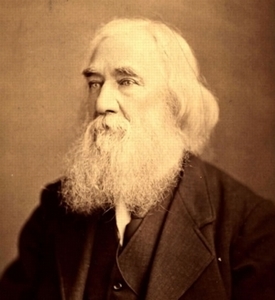

The Works of Lysander Spooner (1808-1887): Vol. 4 (1863-1873)

|

Lysander Spooner (1808-1887) was a legal theorist, abolitionist, and radical individualist who started his own mail company in order to challenge the monopoly held by the US government. He wrote on the constitutionality of slavery, natural law, trial by jury, how binding was the authority of the US Constitution over individuals, intellectual property, paper currency, and banking.

A full list of his Collected Works in both chronological

order of date of publication (useful for seeing how his interests and

ideas changed over time) and a thematic list by topic can be found here.

The numbers refer to the work’s place in the chronological order.

More information about Spooner and his work:

- Spooner's main bio page: </people/4664>.

- School of Thought: Abolition of Slavery </collections/33>.

- School of Thought: 19th Century Natural Rights Theorists </collections/38>.

The Second Edition

We began (2009-10) putting Spooner's works online book by book and pamphlet by pamphlet over a period of several years. The second edition of his Works will be 5 volumes in chronological order by date of publication. The works will be available temporarily here in HTML. They can be ound in facsimile PDFhere as well:

The Collected Works of Lysander Spooner (1834-1886), in 5 volumes (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2015).

- Vol. 1 (1834-1850) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner1> or PDF </titles/2294>.

- Vol. 2 (1853-1855) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner2> or PDF </titles/2295>.

- Vol. 3 (1858-1862) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner3> or PDF </titles/2296>.

- Vol. 4 (1863-1873) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner4> or PDF </titles/2297>.

- Vol. 5 (1875-1886) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner5> or PDF </titles/2298>.

The entire works of Spooner are searchable from the main bio page </people/4664>.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

The texts are in the public domain.

This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Table of Contents

Vol. 4 (1863-1873):

- T.19 Articles of Association of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts (1863).

- T.20 Considerations for Bankers, and Holders of United States Bonds (1864).

- T.21 A Letter to Charles Sumner (1864).

- T.22 No Treason, No. 1 (1867).

- T.23 No Treason. No II.The Constitution (1867).

- T.24 Senate-No. 824. Thomas Drew vs. John M. Clark (1869).

- T.25 No Treason. No VI. The Constitution of No Authority (1870).

- T.26 A New Banking System: The Needful Capital for Rebuilding the Burnt District (1873).

The Works↩

T.19 Articles of Association of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts (1863).↩

[19.] Articles of Association of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts (n.p., 1863).

- also online Shorter Works, vol. 2: </titles/2292#lf1531-02_head_004>

ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION OF THE SPOONER COPYRIGHT COMPANY FOR MASSACHUSETTS.

ARTICLE I.

This Association shall be called the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts.

ARTICLE II.

The Trustees of the Capital of this Association shall be Robert E. Apthorp, and Charles Hale Browne, both of Boston, and Jacob B. Harris, of Abington, all in the State of Massachusetts, the survivors and survivor of them, and their successors appointed as hereinafter prescribed.

ARTICLE III.

The Capital of said Company shall consist of all the rights conveyed to said Trustees, by Lysander Spooner, by a trust deed, of this date, of which the following is a copy, to wit:

Trust Deed.

Know all men by these presents, that I, Lysander Spooner, of Boston, in the County of Suffolk, and Commonwealth of Massachusetts, in consideration of one dollar to me paid by Edition: current; Page: [2] Robert E. Apthorp, of Boston, Esquire, Charles Hale Browne, of Boston, Physician, and Jacob B. Harris, of Abington, Esquire, all in the State of Massachusetts, Trustees of the Capital of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, the receipt of which I hereby acknowledge, and in further consideration of the promises made and entered into, by said Trustees, in the Articles of Association of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, (which Articles bear even date herewith,) have given, granted, and conveyed, and do hereby give, grant, and convey, to said Apthorp, Browne, and Harris, and to the survivors and survivor of them, and to their successors duly appointed, in their capacity of Trustees as aforesaid, and not otherwise, all my right, title, and interest, for and within said Commonwealth of Massachusetts, (except as is hereinafter excepted,) in and to the “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” for which a copyright was granted, under that title, to me, by the United States of America, in the year 1860.

I also, for the considerations aforesaid, hereby give, grant, and convey unto said Apthorp, Browne, and Harris, and to the survivors and survivor of them, and their successors in said trust, in their capacity as Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and not otherwise, all my right, title, and interest, for and within said Commonwealth of Massachusetts, (except as is hereinafter excepted,) in and to eleven other copyrighted papers, which are included in said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” but for which separate copyrights were also granted to me by the United States of America, in the year 1860. Said papers are respectively entitled as follows, to wit: 1. Stock Mortgage. 2. Mortgage Stock Currency. 3. Transfer of Productive Stock in Redemption of Circulating Stock. 4. Re-conveyance of Productive Stock from a Secondary to a Primary Stockholder. 5. Primary Stockholder’s Certificate of Productive Stock of the following named Mortgage Stock Banking Company. 6. Primary Stockholder’s Edition: current; Page: [3] Sale of Productive Stock of the following named Mortgage Stock Banking Company. 7. Secondary Stockholder’s Certificate of Productive Stock of the following named Mortgage Stock Banking Company. 8. Secondary Stockholder’s Sale of Productive Stock of the following named Mortgage Stock Banking Company. 9. Sale, by a Primary Stockholder, of his right to Productive Stock in the hands of a Secondary Stockholder. 10. Trustee’s Bond. 11. Trust Deed. And were copyrighted under those titles respectively.

I also, for the considerations aforesaid, hereby give, grant, and convey to said Apthorp, Browne, and Harris, and to the survivors and survivor of them, and to their successors in said trust, in their capacity as Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and not otherwise, all right, property, interest, and claim, of every name and nature whatsoever, which, as the inventor thereof, I have, or can have, (for and within the State of Massachusetts only,) either in law, equity, or natural right, in and to the banking system, or Currency system, (as an invention,) and every part thereof, which is embodied or described in the said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and in the other copyrighted papers hereinbefore mentioned, whether such right, property, interest, and claim now are, or ever hereafter may be, secured to me, my heirs, or assigns, by said copyrighted Articles and papers, or by patent, or by statute, or by common, or constitutional, or natural law—subject only to the exceptions and reservations hereinafter made in behalf of banking companies, whose capitals shall consist either of rail-roads and their appurtenances, or of mortgages or liens upon rail-roads and their appurtenances, (situated within the State of Massachusetts and elsewhere,) or of lands or other property situated outside of the State of Massachusetts.

It being my intention hereby to convey, and I do hereby convey, to said Apthorp, Browne, and Harris, and to the survivors and survivor of them, and to their successors in said trust, in their capacity as Trustees as aforesaid, and not otherwise, all my Edition: current; Page: [4] right, title, and interest, of every name and nature whatsoever, either in law, equity, or natural right, (except as is hereinafter excepted,) in and to said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and in and to all the other beforementioned copyrighted papers, and in and to the invention embodied or described in said Articles and papers, so far as, and no farther than, the same may or can be used by Banking Companies, whose banking capital shall consist of lands, or other real property, (except rail-roads and their appurtenances,) or of mortgages or liens upon lands, or other real property, (except rail-roads and their appurtenances,) situate wholly within said Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and not elsewhere.

And I also, for the considerations aforesaid, hereby give, grant, and convey to said Apthorp, Browne, and Harris, and to the survivors and survivor of them, and to their successors in said trust, in their capacity as Trustees of the capital of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and not otherwise, full power and authority to grant to any and all Banking Companies that may hereafter be lawfully licensed by said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and organized under said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” or any modification thereof, within said Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and upon capital consisting of lands or other real property, (except rail-roads and their appurtenances,) or of mortgage or liens upon lands, or other real property, (except rail-roads and their appurtenances,) situate exclusively within said State of Massachusetts, the right and liberty to establish and maintain offices at pleasure in any and all other States and places within the United States of America, or any Territories or Districts thereto belonging, or supposed or believed to belong thereto, for the sale, loan, and redemption both of their Productive and Circulating Stock, without any charge, let, or hindrance by or from me, the said Spooner, or my heirs or assigns.

And I hereby expressly reserve to myself, my heirs and assigns, the full and exclusive right to grant to any and all Edition: current; Page: [5] Banking Companies, that may be organized under said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” or any modification thereof, and whose capitals shall consist wholly of lands, or other property, or of mortgages upon lands, or other property, situate wholly outside of the State of Massachusetts, the right to establish and maintain at pleasure, within the State of Massachusetts, offices for the sale, loan, and redemption both of their Productive and Circulating Stock, without any charge, let, or hindrance by or from said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, or the Trustees thereof.

And I do also hereby expressly reserve to myself, my heirs, and assigns, the full and exclusive right to the sale and use of said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” or any parts or modification thereof, so far as the same may or can be used by Banking Companies, whose capitals shall consist exclusively of rail-roads and their appurtenances, or of mortgages or liens upon rail-roads and their appurtenances, situate either within the State of Massachusetts, or elsewhere.

The rights hereby conveyed are to constitute, and are hereby conveyed solely that they may constitute, the capital, or capital stock, of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and are to be held, used, employed, managed, and disposed of by the Trustees of said Company in accordance, and only in accordance, with the Articles of Association of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts; which Articles have been agreed to by said Apthorp, Browne, and Harris, and me, the said Spooner, and bear even date herewith.

To have and to hold to said Apthorp, Browne, and Harris, and to the survivors and survivor of them, and to their successors in said trust, in their capacity as Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and not otherwise, all the rights hereinbefore described to be conveyed to them, to be held, used, employed, managed, and disposed of, in accordance, and only in accordance, with said Articles of Association of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, forever.

Edition: current; Page: [6]And I do hereby covenant and agree to and with said Apthorp, Browne, and Harris, the survivors and survivor of them, and their successors in said trust, in their capacity as Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and not otherwise, that I am the true, sole, and lawful owner of all the rights hereinbefore mentioned as intended to be hereby conveyed; that they are free of all incumbrances; that I have good right to sell and convey the same as aforesaid; and that I will, and my heirs, executors, and administrators shall, forever warrant and defend the same to the said Apthorp, Browne, and Harris, and to the survivors and survivor of them, and to their successors in said trust, in their capacity as Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and not otherwise, against the lawful claims and demands of all persons.

In witness whereof, I, the said Lysander Spooner, have set my hand and seal to three copies of this deed, on this twentieth day of March, in the year eighteen hundred and sixty three.

| Signed, sealed, and delivered in presence of | ||

| BELA MARSH, } | LYSANDER SPOONER. | [SEAL.] |

| THOMAS MARSH. } |

Then Lysander Spooner personally acknowledged the above instrument to be his free act and deed.

Before me Geo. W. Searle, Justice of the Peace.

ARTICLE IV.

1. The aforesaid capital shall be held in joint stock by the Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, at the nominal value of one million dollars, and divided into two thousand shares, of the nominal value of five hundred dollars each.

2. Said shares shall be numbered consecutively from one to two thousand inclusive.

Edition: current; Page: [7]3. They are all hereby declared to be the property of said Lysander Spooner, and shall be entered as such upon the books of the Trustees.

ARTICLE V.

Whenever any of the before-named shares of Stock shall be conveyed, the particular numbers borne by the shares conveyed shall be specified, both in the instrument of conveyance, (where that shall be reasonably practicable,) and on the books of the Trustees.

ARTICLE VI.

1. Any person, who shall, at any time, be a holder of fifty shares of the Stock of said Copyright Company, may, for the time being, either be a Director, or appoint one in his stead, at his election. And for every additional fifty shares, so owned by him, he may appoint an additional Director. Or he may, by himself or by proxy, give one vote, as Director, for each and every fifty shares of Stock of which he may, at the time, be the owner. Provided that no person, by purchasing Stock, shall have the right to be, or appoint, a Director for the same, so long as there shall be in office a Director previously appointed for the same Stock.

2. Any two or more persons, holders respectively of less than fifty shares, but holding collectively fifty or more shares, may, at any time, unite to appoint one Director for every fifty shares of their Stock. Provided, however, that no persons, purchasing Stock, shall have the right to appoint a Director on account of such Stock, so long as there shall be in office a Director previously appointed for the same Stock.

3. All appointments of Directors shall be made by certificates addressed to, and deposited with, the Trustees, and stating specifically the shares for which the Directors are appointed respectively. And such appointments shall continue until the first day of January Edition: current; Page: [8] next after they are made, unless they shall be, before that time, rescinded (as they may be), by those making them.

4. The Board of Directors may, by ballot, choose their President, who shall hold his office during the pleasure of the Board. Whenever there shall be no President in office, by election, the largest Stockholder who shall be, in person, a member of the Board, shall be the President.

5. The Directors, by a majority vote of their whole number, may fix their regular times of meeting, and the number that shall constitute a quorum for business.

6. The Directors shall exercise a general supervision, and so far as they may see fit, a general control, over the expenditures and all other business affairs of the Company. They may appoint a Treasurer, Attorney, and other clerks and servants of the Company; and take bonds, running to the Trustees, for the faithful performance of their duties.

7. The Directors shall keep a record of all their proceedings; and shall furnish to the Trustees written copies of all orders, rules, and regulations which may be adopted by the Directors, for the guidance of the Trustees.

8. The Directors shall receive no compensation for the performance of their ordinary duties. But they may vote a reasonable compensation to the President. And for any extraordinary services, performed by individual Directors, reasonable compensation may be paid.

ARTICLE VII.

1. With the consent of the Directors, the Trustees may grant to Banking Companies, whose capitals shall consist wholly of mortgages upon lands situated within the State of Massachusetts, and to none others, the right to use the aforesaid “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and all the other before-mentioned copyrighted papers, (that are included in said Articles of Association,) so far as it may be convenient Edition: current; Page: [9] and proper for such Banking Companies to use said Articles and other copyrighted papers in carrying on the business of said Companies as bankers, and not otherwise.

2. The license granted to said Banking Companies to use said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and other copyrighted papers, shall be granted by an instrument in the following form, (names, dates, and numbers being changed to conform to the facts in each case,) to wit:

License to a Mortgage Stock Banking Company.

Be it known that we, A——— A———, B——— B———, and C——— C———, all of ———, in the State of Massachusetts, Trustees of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, by virtue of the power and authority in us vested by the Articles of Association of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and having the consent of the Directors of said Company hereto, in consideration of one thousand dollars, to us paid by D——— D———, E——— E———, and F——— F———, all of Princeton, in the County of Worcester, and Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Trustees of the Princeton Banking Company,—a Mortgage Stock Banking Company, located in said town of Princeton, and having its capital of one hundred thousand dollars, made up of mortgages upon lands and buildings in said town of Princeton, and this day organized under the “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” for which a copyright was granted, by the United States of America, to Lysander Spooner, in the year 1860,—the receipt of which sum of one thousand dollars is hereby acknowledged, do hereby give, grant, and convey unto said Princeton Banking Company, and to said Trustees of said Princeton Banking Company, and to the survivors and survivor of them, and to their successors in said trust, in their capacity as trustees of said Princeton Banking Company, and not otherwise, the right, privilege, and license to Edition: current; Page: [10] use one set (a copy of which is hereto annexed) of said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and of eleven other papers, that were copyrighted by said Spooner, in 1860, and are included in said Articles, and are respectively entitled as follows, to wit: 1. Stock Mortgage. 2. Mortgage Stock Currency. 3. Transfer of Productive Stock in Redemption of Circulating Stock. 4. Re-conveyance of Productive Stock from a Secondary to a Primary Stockholder. 5. Primary Stockholder’s Certificate of Productive Stock of the following named Mortgage Stock Banking Company. 6. Primary Stockholder’s Sale of Productive Stock of the following named Mortgage Stock Banking Company. 7. Secondary Stockholder’s Certificate of Productive Stock of the following named Mortgage Stock Banking Company. 8. Secondary Stockholder’s Sale of Productive Stock of the following named Mortgage Stock Banking Company. 9. Sale, by a Primary Stockholder, of his right to Productive Stock in the hands of a Secondary Stockholder. 10. Trustee’s Bond. 11. Trust Deed.

Said Princeton Banking Company, and the Trustees thereof, are hereby authorized to use said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and all the other copyrighted papers before mentioned, so far as the same may or can be legitimately used in doing the banking business of said Princeton Banking Company, and not otherwise; and to continue such use of them during pleasure.

The right, privilege, and license hereby granted, are granted subject to these express conditions, viz: that all copies of said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and of all the other before mentioned copyrighted papers, which may ever hereafter be printed or used by said Princeton Banking Company, or the Trustees thereof, shall be respectively exact and literal copies of those hereto annexed; and shall have the name of said Princeton Banking Company (and of no other Banking Company) printed in them; and shall also, each and all of them, bear the proper certificate of copyright in these Edition: current; Page: [11] words and figures, to wit: “Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1860, by Lysander Spooner, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States, for the District of Massachusetts.” Said certificate to be printed immediately under, and next to, the titles of the articles and papers copyrighted, in the same manner as in the copies hereto annexed. Subject to these conditions, said Princeton Banking Company, and the Trustees thereof, are to have the right of printing so many copies of each and all the before mentioned papers, as they may find necessary or convenient in carrying on the business of said Company as bankers, under their present name and organization, and not otherwise.

And furthermore, for the consideration aforesaid, we, the aforesaid Trustees of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, hereby give, grant, and convey to said Princeton Banking Company, and to the Trustees thereof, in their capacity as such Trustees, and not otherwise, the right, liberty, and privilege to establish at pleasure offices in any and all other towns and places, other than said Princeton, not only in said State of Massachusetts, but in any and all other States of the United States, and in any and all Territories, Districts, or other places, belonging, or supposed to belong, to the United States, for the sale, loan, and redemption both of their Circulating and Productive Stock, free of all charge, let, or hindrance by or from the said Lysander Spooner, or any other persons claiming by, through, or under him.

In Witness Whereof, we, the said A——— A———, B——— B———, and C——— C———, Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, have set our hands and the seal of said Copyright Company to ——— copies of this License, this ——— day of ———, in the year eighteen hundred and ———.

| SEAL. | A——— | A———, } | Trustees of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts. |

| B——— | B———, } | ||

| C——— | C———, } |

Signed, sealed and delivered in presence of

Edition: current; Page: [12]3. The signatures of two of the Trustees (and of one, if at the time there shall be but one Trustee), to any license, shall be sufficient in law.

4. To every copy of the License granted as aforesaid shall be attached one complete set of the papers licensed by it to be used, to wit: one copy of the “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and separate copies of each of the other eleven copyrighted papers hereinbefore described, and included in said Articles.

ARTICLE VIII.

1. Whenever the Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, shall grant to any Banking Company the right to use said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and the other copyrighted papers included therein, they (the said Trustees), shall superintend the printing of said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers, (as well those that shall be printed together, as those that shall be printed separately,) and shall see that they are all correct in form, following strictly the copies of the same which are hereto annexed, (changing only dates, numbers, names of persons and places, &c., to make them correspond with the facts in each case,) and shall see that they all have printed in them the name of the particular Banking Company for whose use they are designed, and of no other; and shall also see that they each and all have the proper certificate of copyright printed on said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers, immediately under, and next to, the titles thereof respectively, in the following words and figures, to wit: “Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1860, by Lysander Spooner, in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the District of Massachusetts.”

2. And said Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts shall retain at least five copies (one for each of themselves, one for the Directors of said Copyright Company, and Edition: current; Page: [13] one for said Lysander Spooner, his heirs, executors, administrators, or assigns, if demanded by him or them), of every set of said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers, the use of which may be granted to any Banking Company, or Banking Companies; said copies to be verified by the certificate and signatures both of said Trustees themselves, and of the Trustees of the Banking Companies to whom the right of using said “Articles,” and other copyrighted papers, shall be granted.

3. And the copies so retained by the Trustees and Directors of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, (except those retained for said Spooner, his heirs, executors, administrators, and assigns, which shall be delivered to him or them on demand,) shall be forever preserved for the benefit, and as the property, of said Copyright Company; each Trustee retaining the custody of one copy; and all copies in the possession of any one Trustee being transferred to his immediate successor forever, and receipts taken therefor.

ARTICLE IX.

1. Previous to granting to any Banking Company the right to use said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and other copyrighted papers before mentioned, the Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, and also the Directors of said last named Company, or a committee or agent thereof, (if the Directors shall see fit either to investigate the matter for themselves, or to appoint a committee or agent to act for them,) shall carefully and faithfully examine all the mortgages which shall be proposed as the capital of such Banking Company, and all certificates and other evidences that may be offered to prove the sufficiency of the mortgaged property, the validity of the mortgages themselves, and the freedom of the mortgaged premises from all incumbrances of every name and nature whatsoever, unless it be the liens of Mutual Insurance Companies for assessments on account of insurance of the premises.

Edition: current; Page: [14]2. And the right to use said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and other copyrighted papers shall not be granted to any Banking Company, unless two at least of the Trustees of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts (and also the Directors, or a committee or agent thereof, if the Directors, or a committee or agent thereof, shall act on the subject), shall be reasonably satisfied that each and every piece of mortgaged property is worth, at a fair and just valuation, double the amount for which it is mortgaged to the Trustees of the Banking Company, and that it is free of all prior incumbrance of every name and nature whatsoever, (except for insurance as aforesaid,) and that the title of the mortgagor is absolute and perfect.

3. The Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts (and also the Directors, or a committee or agent thereof, if they shall see fit to act on the subject), shall require each and every mortgagor to give to the Trustees of the Banking Company a good and ample policy of insurance against fire upon the buildings upon any and all property mortgaged as aforesaid, unless they shall be satisfied that the mortgaged property is worth, independently of the buildings, double the amount of the mortgage.

ARTICLE X.

1. The price or premium demanded or received, by said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, for the use of said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and the other copyrighted papers before mentioned, by any one Banking Company, shall not (except as hereinafter provided), exceed one per centum upon the capital of the Banking Company licensed to use said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers. By this is meant, not one per centum per annum, but one per centum outright; the Banking Company being then free to continue the use of said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers during pleasure.

Edition: current; Page: [15]2. In addition to the one per centum before mentioned, and as a preliminary to either granting or refusing to any proposed Banking Company the right to use said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers, said Copyright Company may, by vote of the Directors, demand and receive a sum not exceeding one tenth of one per centum on the capital of such proposed Banking Company, as compensation for the labor of the Trustees, and Directors, and their committee or agent, in examining the mortgages and other papers of such Banking Company.

3. The Copyright Company aforesaid may also, by vote of the Directors, charge an additional sum, not exceeding one tenth of one per centum on the capital of any Banking Company, as a compensation for the labor of the Trustees of the former Company, (and of the Directors, or any committee, or agent thereof, if they shall act on the matter,) in superintending the printing, stereotyping, or engraving of said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers to be used by such Banking Company.

4. If said Copyright Company shall ever themselves (as they are hereby authorized to do), undertake the business of printing, stereotyping, or engraving the “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and other before mentioned copyrighted papers, for the use of the Banking Companies that may be licensed to use said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers, said Copyright Company may demand and receive for such printing, stereotyping, and engraving, and for the paper consumed in so doing, and for any stereotype or engraved plates made by them, and sold to said Banking Companies, any sum not exceeding double the necessary and proper amount actually paid, by said Copyright Company, for the labor employed, and materials consumed, in printing, stereotyping, and engraving said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers, and in making such stereotype and engraved plates; but in ascertaining that amount, no account shall be taken of the rent of buildings owned or leased by said Copyright Company, and occupied in said printing, stereotyping, or engraving; nor of the wear or destruction of Edition: current; Page: [16] any of said Copyright Company’s type, printing presses, or other material or machinery employed in the process of such printing, stereotyping, or engraving; nor of the labor of superintending such processes either by the Trustees, Directors, or agents of said Copyright Company (except as is provided for in the third clause of this Article).

5. Except as is provided for and authorized by the preceding clauses of this Article, said Copyright Company shall not, in any case whatever, neither directly nor indirectly, nor by any evasion, nor on any pretence, whatever, make any charge or demand upon any Banking Company, nor any addition to the before mentioned charges or prices, for the right to use said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and other copyrighted papers, nor for any printed, stereotyped, or engraved copies of said “Articles,” or other copyrighted papers; nor for any stereotyped or engraved plates of said “Articles,” or other copyrighted papers; nor shall said Copyright Company ever hereafter attempt, in any mode, or by any means, either directly or indirectly, to increase the receipts or profits of said Copyright Company, (beyond the amounts hereinbefore specified,) neither from the licenses granted to Banking Companies to use said “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and other copyrighted papers; nor by furnishing to Banking Companies printed or engraved copies of said “Articles,” or other copyrighted papers, or stereotyped or engraved plates of said “Articles,” or other copyrighted papers, unless under the following circumstances and conditions, to wit: During the life-time of said Lysander Spooner, and with his formal and written consent, or after his death, without his consent having ever been given, the prices of all kinds before mentioned may be increased at discretion by written and recorded resolutions or orders that shall have been personally signed both by Directors representing in the aggregate not less than three-fourths of the capital stock of said Copyright Company and also by Stockholders owning in the aggregate not less than three-fourths of all Edition: current; Page: [17] the capital stock of said Copyright Company. Provided, however, that, after the death of said Spooner, no such increase of prices or income shall be attempted or adopted, in the manner mentioned, by the votes of Directors and Stockholders, unless a similar increase shall have been first agreed upon to be adopted by similar votes of the Directors and Stockholders of a majority of all similar Copyright Companies that may then be in existence in all the States of the United States.

6. All the before mentioned prices may be reduced at discretion, from the highest amounts named, by votes of the Directors, or of the holders of a majority of the stock.

ARTICLE XI.

With the consent of the Directors, said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts may hold so much real and personal estate as may be needful or convenient for the proper uses and business of said Company, and especially for carrying on the business of printing, stereotyping, and engraving the before mentioned “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and other copyrighted papers, for the use of Banking Companies, that may be licensed, by said Copyright Company, to use said “Articles” and other copyrighted papers.

ARTICLE XII.

Neither said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, nor the Trustees, nor Directors, nor any agent or officer of said Company, shall have power to contract any debt that shall be binding upon the private property of any Stockholder, or compel the sale of his stock. But said Company, through the Trustees, and with the consent of the Directors, may, for legitimate and proper objects, pertaining directly to the proper business of said Company, contract debts that shall pledge, and be binding upon, and operate as a lien upon, all the receipts and revenues of Edition: current; Page: [18] the Company, and all the real and personal estate of the Company, other than the copyright property which constitutes the capital stock of the Company.

ARTICLE XIII.

Each one of the Trustees of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts shall receive, in each year, as compensation for his services as Trustee, five per centum of all the net income of the Company for the year, payable semi-annually, or oftener, at the discretion of the Directors.

ARTICLE XIV.

No dividend shall ever be paid to any Stockholder in said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, except from net income actually accumulated.

ARTICLE XV.

In granting to Banking Companies the right to use the aforementioned “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” and the other copyrighted papers before mentioned, no change shall ever be made from the copies of said “Articles” and other papers hereto annexed, (except the changes of names, dates, numbers, &c., to correspond to the facts in each case,) during the life time of said Lysander Spooner, unless with his formal consent given in writing, and particularly specifying the changes to which he consents. Nor shall any such changes be made, either before or after the death of said Spooner, unless in accordance with a written and recorded vote resolution, or order, signed by a Stockholder or Stockholders personally, (and not by any agent or attorney,) owning, in the aggregate, at least three-fourths of all the capital stock of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts. Nor shall any such changes be made, after the death of said Spooner, unless the same changes Edition: current; Page: [19] shall have been first agreed upon, (in the same manner,) to be adopted by a majority of all the similar Copyright Companies that may then be in existence in all the States of the United States.

ARTICLE XVI.

Any Trustee of said Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, may be removed from his office of Trustee, by the vote or votes of any Stockholder or Stockholders owning, at the time, not less than three-fourths of all the stock of the Company. Said vote or votes shall be expressed by two records, one to be kept by the Trustees, the other by the Directors, and both subscribed by the Stockholder or Stockholders personally, (and not by any agent or attorney,) declaring his or their wish or determination that the Trustee be removed. And such records shall, from the moment of their being so subscribed, and the other Trustees or Trustee notified thereof, operate to cancel all his rights and powers as a Trustee, and vacate his place as Trustee, and make it liable to be filled by another. In subscribing such vote, each Stockholder shall affix to his signature the number of shares of which he shall be, at the time, the holder, and also the particular numbers borne by such shares.

ARTICLE XVII.

Whenever a vacancy shall occur in the office of a Trustee, it may be filled by the vote or votes of any Stockholder or Stockholders owning, at the time, not less than three-fourths of all the stock of the Company. Such vote shall be expressed by two records, one to be kept by the Directors, the other by the Trustees, and both subscribed by the Stockholder or Stockholders personally, and not by any agent or attorney, declaring his or their wish and choice that the individual named shall be the Trustee. And such records, on being deposited with the Directors and Trustees respectively, shall entitle the individual so Edition: current; Page: [20] elected to demand that his appropriate interest, as Trustee, in the capital stock of the Company, be at once conveyed to him by the other Trustees, or Trustee. And upon such interest being conveyed to him, he shall be, to all intents and purposes, a Trustee, equally with the other Trustees, or Trustee. And the instrument conveying to him his interest, as Trustee, in the capital stock of the Company, shall be acknowledged and recorded in accordance with the laws of the United States for the conveyances of copyrights, or any interest therein.

ARTICLE XVIII.

The signatures of any two of the Trustees (or of one, if at the time there shall be but one Trustee) to certificates of the Stock of the Company, shall be sufficient in law.

ARTICLE XIX.

If required by the Directors, the Trustees shall give reasonable bonds for the faithful performance of their duties. Said bonds shall run to the Directors, for and on behalf of the Stockholders collectively and individually.

ARTICLE XX.

The Trustees shall have a seal with which to seal certificates of stock, licenses, and any other papers, to which it may be proper to affix their seal.

ARTICLE XXI.

Transfers of the stock of the Company, not made originally in the books of the Company, shall not be valid, against innocent purchasers for value, until recorded on the books of the Company.

ARTICLE XXII.

The Trustees shall keep books fully showing, at all times, their proceedings, and the affairs of the Company. And these books shall, at all reasonable times, be open to the inspection both of the Directors, and of Stockholders.

ARTICLE XXIII.

Every Stockholder shall be entitled, of right, to one copy of the Articles of Association of the Company.

ARTICLE XXIV.

These Articles of Association of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts, may be altered by the vote or votes of any Stockholder or Stockholders owning, at the time, not less than four fifths of the stock of the Company. Such vote or votes shall be expressed by two records, one to be kept by the Trustees, the other by the Directors, and both subscribed by the Stockholder or Stockholders personally, (and not by any agent or attorney,) declaring in precise terms the alterations to be made. But no alteration shall ever be made, injuriously affecting the previous rights of any Stockholder relatively to any or all other Stockholders. Nor shall any change ever be made affecting the provisions of Articles X and XV. Nor shall any change ever be made in Article XII, without the vote of every Stockholder expressed in the manner aforesaid.

In Witness Whereof, I, the said Lysander Spooner, and we, the sai d Robert E. Apthorp, Charles Hale Browne, and Jacob B. Harris, Trustees as aforesaid, in token of our acceptance of said trust, and of our promise to fulfil the same faithfully and honestly, have set our hands and seals to six copies of these Articles of Association, consisting of twenty-two printed Edition: current; Page: [22] pages, and have also set our names upon each leaf of said Articles, this twentieth day of March, in the year eighteen hundred and sixty-three. We have also, on the same day, set our names upon each leaf of six copies of the “Articles of Association of a Mortgage Stock Banking Company,” hereinbefore mentioned, one copy of which is hereto annexed, consisting of fifty-nine printed pages.

Signed, sealed, and delivered in presence of

T.20 Considerations for Bankers, and Holders of United States Bonds (1864).↩

[20.] Considerations for Bankers, and Holders of United States Bonds (Boston: A. Williams & Co., 1864).

- also online Shorter Works, vol. 2: </titles/2292#lf1531-02_head_008>

CONSIDERATIONS FOR BANKERS.

CONSIDERATIONS

FOR

BANKERS,

and

HOLDERS OF UNITED STATES BONDS.

BY LYSANDER SPOONER.

BOSTON:

A. WILLIAMS & CO., 100 WASHINGTON STREET.

NEW-YORK: American News Company, 121 Nassau Street.

1864.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1864,

By LYSANDER SPOONER

in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the District of Massachusetts.

CONTENTS.

- Chapter I.—Explanation of the Author’s New System of Paper Currency, . . . . . 5

- Chap. II.—The Author’s System Cannot be Prohibited by the States, . . . . . 15

- Chap. III.—The Author’s System Cannot be Taxed, either by the United States, or the States, . 27

- Chap. IV.—The State Governments Cannot Control, nor in any Manner Interfere with, the Author’s System, . . . . . 33

- Chap. V.—Unconstitutionality of the Legal Tender Acts of Congress, . . . . . 37

- Chap. VI.—Unconstitutionality of the United States Banking Act, . . . . . 71

- Chap. VII.—Exchanges under the Author’s System, . 85

- APPENDIX

- The Author’s Copyright, . . . . . . 89

CHAPTER I.: EXPLANATION OF THE AUTHOR’S NEW SYSTEM OF PAPER CURRENCY.

The principle of the system is, that the currency shall represent an invested dollar, instead of a specie dollar.

The currency will, therefore, be redeemable, in the first instance, by an invested dollar, unless the bankers choose to redeem it with specie.

The capital is made up of a given amount of property deposited with trustees.

This capital is never diminished; but is liable to pass into the hands of new holders, in redemption of the currency, if the trustees fail to redeem the currency with specie.

The amount of currency is precisely equal to the nominal amount of capital.

When the currency is returned for redemption, (otherwise than in payment of debts due the bank,) and the trustees are not able, or do not choose, to redeem it with specie, they redeem it by a conditional transfer of a corresponding portion of the capital. And the conditional holder of the capital thus transferred, holds Edition: current; Page: [6] it, and draws interest upon it, until the trustees redeem it, by paying him its nominal value in specie.

Under certain exceptional and extraordinary circumstances, this conditional transfer of a portion of the capital, becomes an absolute transfer; and the conditional holder of the capital transferred, becomes an absolute holder of it—that is, an absolute stockholder in the bank.

In such cases, therefore, the final redemption of the currency consists in making the holders of the currency bona fide stockholders in the bank itself.

To repeat, in part, what has now been said:

The currency, besides being receivable for debts due the bank, is redeemable, first, with specie, if the bankers so choose; or, secondly, by a conditional transfer of a part of the capital.

The capital, thus conditionally transferred, may be itself redeemed, by the bank, on paying its nominal value in specie, with interest from the time of the transfer.

Or, this conditional transfer, of a portion of the capital, may, under certain circumstances, become an absolute transfer.

A holder of currency, therefore, is sure to get for it, either specie on demand; or specie, with interest, from the time of demand; or an amount of the capital stock of the bank, corresponding to the nominal value of his currency.

In judging of the value of the currency, therefore, he judges of the value of the capital; because, in certain contingencies, he is liable to get nothing but the capital for his currency. But if the capital be worth par of specie, or more than par of specie, he infers that his currency will be redeemed, either in specie on demand, or by a temporary transfer of capital; which capital will afterwards be itself redeemed with specie.

All that is necessary to make a bank, under this system, a sound one, is, that its capital shall consist of productive property—its actual value fully equal to, or a little exceeding, its nominal value—and of a kind not perishable, or likely to depreciate in value.

Edition: current; Page: [7]Mortgages, rail-roads, and public stocks will probably be the best capital; and most likely they are the only capital which it will ever be expedient to use.

If further explanation of the nature of the system be needed, at this point, it can be given—more easily, perhaps, than in any other way—by supposing the capital to consist of land—as follows:

Suppose that A is the owner of one hundred, B of two hundred, C of three hundred, and D of four hundred, acres of land; that all these lands are of uniform value, to wit, one hundred dollars per acre; that they will always retain this value; and that they are all under perpetual leases at an annual rent of six dollars per acre.

A, B, C, and D, put all these lands into the hands of trustees, to be held as banking capital; making an aggregate capital of one hundred thousand dollars. Their rights, as lessors, going with the lands into the hands of the trustees—that is, the trustees being authorized to receive the rents, and apply them to the uses of the bank, if they should be needed.

A, B, C, and D, then, are the bankers, doing business through the trustees.

Their dividends, as bankers, it is important to be noticed, will consist both of the rents of the lands, and the profits of the banking; making dividends of twelve per cent. per annum, if the banking profits should be six per cent.

The banking will be done in this way—

The trustees will make certificates for one, two, three, five, ten dollars, and so on, to the aggregate amount of one hundred thousand dollars; corresponding to the whole value of the lands.

These certificates will be issued for circulation as currency, by discounting notes, &c.

Each certificate will be, in law, a lien upon the lands for one dollar, or for the number of dollars expressed in the certificate.

The conditions of this lien will be these—

1. That these certificates shall be a legal tender in payment of all debts due the bank.

Edition: current; Page: [8]2. That when one hundred dollars of these certificates shall be presented for redemption, the trustees, unless they shall redeem them with specie, shall give the holder a conditional title to one acre of land. This conditional title will empower the holder to demand of the trustees rent for that acre, at the rate of six dollars per annum, until they redeem the acre itself, by paying him an hundred dollars in specie for it. And no dividends shall be made by the trustees, to the bankers, (A, B, C, and D,) either from the rents of any of the other lands, or from the profits of banking, until this conditional title to the one acre, given to the holder of currency, shall have been cancelled, by the payment of the hundred dollars in specie, with interest, or rent, for the time the conditional title shall have been in his hands.

3. That when certificates are presented for redemption, in sums less than one hundred dollars, the trustees, unless they redeem them with specie on demand, shall redeem them with specie, (adding interest, except on small sums,) before making any dividends, either of rents, or banking profits, to the bankers (A, B, C, and D).

4. Whenever an acre of land shall have been conditionally transferred in redemption of currency, a corresponding amount of currency (one hundred dollars) must be reserved from circulation, until that acre shall have been redeemed by the bank; to the end that there may never be in circulation a larger amount of currency, than there is of land, in the hands of the bankers, with which to redeem it.

5. So long as any of the lands shall remain the property of the original bankers, (A, B, C, and D,)—free of any conditional title, as before mentioned—the trustees will have the right, as their agents, to cancel all conditional titles, by paying an hundred dollars in specie for each acre, with interest, (or rent,) at the rate of six per cent. per annum, during the time the conditional title shall have been outstanding. And the trustees must do this, before they make any dividends, either of rents, or banking profits, to the bankers themselves.

Edition: current; Page: [9]But if, at any time, the banking shall be so badly managed, as that it shall become necessary for the trustees to give conditional titles to the whole thousand acres, (constituting the entire capital of the bank), the rights of the original bankers (A, B, C, and D) in the lands, shall then be absolutely forfeited into the hands of those holding the conditional titles; who will then become absolute owners of them (as banking capital, in the hands of the same trustees)—in the same manner as A, B, C, and D had been before; and will go on banking with them in the same way as A, B, C, and D had done, and through the agency of the same trustees.

This currency, it will be seen, must necessarily be forever solvent—supposing, as we have done, that the lands retain their original value. It will be absolutely incapable of insolvency; for there can never be a dollar of currency in circulation, without there being a dollar of land, in the hands of the bankers, (or their trustees,) which must be transferred (one acre of land for a hundred dollars of currency) in redemption of it, unless redemption be made in specie. All losses, therefore, fall upon the bankers, (in the loss of their lands,) and not upon the bill holders. If the bankers should fail—that is to say, if they should be compelled to transfer all their lands in redemption of their circulation—the result would simply be, that the lands would pass, unincumbered, into the hands of a new set of holders—to wit, the conditional holders—who would have received them in redemption of the currency—and who would proceed to bank upon them, (reissue the certificates, and redeem them, if necessary, by the transfer of the lands,) in the same way that their predecessors had done. And if they too, should lose all the lands, by the transfer of them in redemption of the currency, the lands would pass, unincumbered, into the hands of still another set of holders, (the second body of conditional holders, who will now become absolute holders,) who would bank upon them, as the others had done before them. And this process would go on indefinitely, as often as one set of bankers should Edition: current; Page: [10] fail (lose all their lands). Whenever one set of bankers should have made such losses as to compel the conditional transfer of all their lands, the conditional transfers would become absolute transfers, and the lands would pass absolutely into the hands of a new set of holders (the conditional holders); and the bank, as a corporation, would be just as solvent as at first. So that, however badly the banking business should be conducted, and however frequently the bankers might fail, (if transferring all their capital (lands), in redemption of their circulation, may be called failing,) the bank itself, as a corporation, could not fail. That is to say, its circulation could never fail of redemption. The lands (the capital) would forever remain intact; forever equivolent to the circulation; and forever subject to a compulsory demand in redemption of the circulation. In this way all losses necessarily fall upon the bankers, (in the loss of their capital, the lands,) and not upon the bill holders, who are sure to get the capital (lands), dollar for dollar, for their currency, if they do not get specie.

From the preceding explanation it will be seen that, if all lands were of an uniform value, and were to retain that value in perpetuity, it would be perfectly easy to use them as banking capital, under the author’s system, and thus create the most abundant and solvent currency that could be desired.

But all lands are not of a uniform value; and, therefore, they cannot be used, acre by acre, as banking capital, under this system. Nevertheless, by means of mortgages, lands may be used as banking capital; since mortgages upon lands can be made to any desirable extent, and all of a uniform value; or at least nearly enough so for all practical purposes. And this value they will retain in perpetuity.

The real estate of this country amounts to some ten thousand millions of dollars. Mortgaged for only half its real value, it would furnish banking capital to the amount of five thousand millions of dollars.

The rail-roads that we now have, and those that we shall have, Edition: current; Page: [11] taken at only half their value, would furnish several hundred millions more of good banking capital.

There will probably also be two thousand millions, or more, of United States Stocks, which, if they should stand permanently at par, or thereabouts, will make good banking capital.

There is, therefore, no more occasion for a scarcity of currency, than for a scarcity of air.

And this currency would all be solvent, stable, and furnished at the lowest rate of interest at which the business of banking could be done.

Under such a system there could never be another crisis; the prices of property would be stable; the rate of interest would always be moderate; industry would be uninterrupted, and much more diversified than it ever hitherto has been; and prosperity would necessarily be universal.

No evils could result from the great amount of currency furnished by this system; for no more would remain in circulation than would be wanted for use. By returning it to the bank for redemption, the holder would either get specie for it, or have it redeemed by the conditional transfer to him of a part of the capital, on which he would draw interest, until the capital so transferred to him, should either be itself redeemed with specie, or made an absolute property in his hands. Currency, therefore, returned for redemption, and not redeemed with specie, is really put on interest, by being redeemed by the conditional transfer of interest-bearing capital. Whenever, therefore, if ever, the prices of property should become so high as not to yield as good an income as money at interest (the interest being paid in specie), the holders of currency would return it to the banks for redemption, beyond the ability of the banks to pay specie. The banks would be compelled to redeem it by the conditional transfer of interest-bearing capital; and thus take it out of circulation.

In short, the currency represents a dollar at interest, instead of a dollar in specie; and whenever it will not buy, in the market, property that is worth as much as money at interest, Edition: current; Page: [12] (the interest payable in specie,) it will be returned to the bank, and put on interest, (by being redeemed in interest-bearing capital,) and thus taken out of circulation. No more currency, therefore, would remain in circulation, than would be wanted for use, the prices of property being measured by the value of an interest-bearing dollar, instead of a specie dollar, if there should be a difference between the two.

Such is, perhaps, as good a view of the general principles of the system, as can be given in the space that can be spared for that purpose. For a more full description, reference must be had to the pamphlet containing the system itself, with the Articles of Association, that will be needed by the banking companies. In the Articles of Association, the system is more fully developed, and the practical details more fully given, than they can be in any general description of the system.*

The recent experience of this country, under a currency redeemable only by being received for taxes, and made convertible at pleasure into interest-bearing bonds (U. S.), is sufficient to demonstrate practically—what is so nearly self-evident in theory as scarcely to need any practical demonstration—that under a system like the author’s, where the currency (when not redeemed in specie on demand) is convertible at pleasure into solvent interest-bearing stocks, there could never be a redundant currency in actual circulation, nor any undue inflation in the prices of property. That experience proves that currency issued, and not needed for actual commerce, at legitimate prices, will be converted into the interest-bearing stocks which it represents, and thus taken out of circulation, rather than used to inflate prices beyond their legitimate standard.†

Edition: current; Page: [13]This experience of the United States, with a currency convertible into interest-bearing bonds, ought, therefore, to extinguish forever all the hard money theories as to the indefinite inflation of prices by any possible amount of solvent paper currency. It ought also to extinguish forever all pretence that a paper currency should always be redeemable in specie on demand; a pretence that is merely a branch of the hard money theory. This experience ought to be taken as proving that other values than those existing in gold and silver coins—values, for example, existing in lands, rail-roads, and public stocks—can be represented by a paper currency, that shall be adequate to all the ordinary necessities of domestic commerce; and consequently that we can have, at all times, as much paper currency as our domestic industry and commerce can possibly call for; and that the frequent revulsions we have hitherto had—owing to our dependence upon a currency legally payable in specie on demand, and therefore liable to contraction whenever specie leaves the country—are wholly unnecessary. This experience ought, therefore, to serve as a practical condemnation of all restraints upon the most unlimited paper currency, provided only that such currency be solvent, and actually redeemable, at the pleasure of the holder, in the property which it purports to represent.

Substantially the same things are proved by the experience of England. The immense amount of surplus money in that country is not used to inflate prices at home; but seeks investment abroad. It is sent all over the world, either in loans to Edition: current; Page: [14] governments, or as investments in private enterprises, rather than used to inflate prices at home beyond their true standard.

The experiences of the two countries, therefore, demonstrate that there is no such thing possible as an undue inflation of prices, by a solvent paper currency — that is, a currency always redeemable in the specific property it purports to represent. And such a currency is that which would be furnished by the author’s system; for the property represented by it is always deliverable, dollar for dollar, in redemption of the currency itself.

CHAPTER II.: THE AUTHOR’S SYSTEM CANNOT BE PROHIBITED BY THE STATES.

The author holds his system by a copyright on the Articles of Association, that will be needed by the banking companies. His system, therefore, stands on the same principle with patents and copyrights. And the use of it can no more be prohibited by the State governments, than can the use of a patented machine, or the publication of a copyrighted book.

The Constitution of the United States expressly gives to Congress “power to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing, for limited times, to authors and inventors, the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” And the laws passed by Congress, in pursuance of this power, are “the supreme law of the land, * * * any thing in the laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.”

If the State governments could prohibit the use of an invention, or the publication of a book, which the United States patent or copyright laws have secured to an inventor or author, the whole “power of Congress to promote the progress of science and useful arts,” by patent and copyright laws, could be defeated by the States.

Some persons may imagine that, whatever may be the right secured to inventors, by patents, the right secured to authors, by copyrights, is only a right to publish their ideas; leaving the State governments still free to prohibit the practical use of the ideas themselves. But this is a mistake. Of what avail would be the publication of ideas, if they could not be used? How utterly ridiculous and futile would be the idea of securing to the people a mere knowledge of “science and useful arts,” with no Edition: current; Page: [16] right, on their part, to apply them to the purposes of life. How could Congress “promote the progress of science and useful arts,” if the people were forbidden to practise them? The right secured, therefore, is not a mere right of publication, but also a right of use.

The objects of patents and copyrights are identical, viz.: to secure to inventors and authors, and through them to the people — against all adverse legislation by the States — the practical enjoyment and use of the ideas patented and copyrighted.

Copyrights, it must be observed, are not granted, as some may suppose, for mere words — for the words of all books were the common property of mankind before the books were copyrighted; and they remain common property afterwards. The copyright, therefore, is for the ideas, and only for the ideas, which the words are used to convey, or describe.

In copyrights, therefore, equally as in patents, the right secured is the right to ideas; that is, to those ideas that are original with the authors of the books copyrighted. And the right thus secured to ideas, is the right, on the part of the author, not only to reduce those ideas to practical use himself, but also to sell them to others for practical use.

If the right, secured to authors by copyrights, were simply a right to publish their ideas, but not to use them, nor sell them to others to be used, the most important knowledge, conveyed by books, might remain practically forbidden treasures, if the State governments should choose to forbid their use.

These conclusions are natural and obvious enough; but as the point is one of great importance, it may be excusable to enforce it still further.

The ground here taken, then, is, that a State government has no more constitutional power to prohibit the practical use of any knowledge conveyed by a copyrighted book, than it has to prohibit the publication or sale of the book itself.

The sole object of the copyright laws are to encourage the production of ideas for the enjoyment and use of the people; to Edition: current; Page: [17] secure to the people the right to enjoy and use those ideas; and to secure to authors compensation for their ideas. All these objects would be defeated, if the States could interfere to prevent the use of the ideas thus produced; because if the ideas could not be used, there would be no sale for the books; and consequently authors would get no pay for writing them; and would have no sufficient motive to write or print them.

It is an axiom in law, that where the means are secured, the end is secured; that the means are secured solely for the sake of the end. It would be as great an absurdity in law, as in business, to secure the means, and not the end; to plant the seed, and abandon the crop; to incur the expense, and neglect the profits. What an absurdity, for example, would it be for the law to secure a man in the possession of his farm, but not in his right to cultivate it, and enjoy the fruits. What an absurdity would it be for the law to secure men in the possession of steam engines, but not in the right to use them. But these would be no greater absurdities than it would be for the law to secure to the people a knowledge of “science and useful arts,” but not the right to use them.

The sole object of the law in securing to all men the possession of their property of all kinds, is simply that they may use it, and have the benefit of it. And the sole object of the laws, that secure to the people knowledge — which is but a species of property, and a most valuable kind of property — is that they may use it, and promote their happiness and welfare by using it.

An illustration of the principle, that where the means are secured, the end is secured, is seen in the constitutional provision that “the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” This provision does not secure to the people a mere naked “right to keep and bear arms” — for that right would be of no practical value to them. But it secures the right also to use them in any and every way that is naturally and intrinsically just and lawful; for that is the only end the people can have in view in “keeping and bearing arms.”

Edition: current; Page: [18]On the same principle, too, if the Constitution had declared that “the right of the people to buy and keep food should not be infringed,” it would thus have guaranteed to them, not merely “the right to buy and keep food,” but also the right to eat the food thus bought and kept; because the eating would be the only end that could be had in view in buying and keeping food.

Another illustration of the same principle is found in the constitutional provision that “Congress shall have power to coin money, and fix the standard of weights and measures.” Have the States any power to forbid the people to buy and sell the money coined by the United States? Or to forbid the people to use the standard weights and measures fixed by the United States? Certainly not. Although the Constitution does not say it in express words, it does say, by necessary implication, that the money, coined by the United States, may be freely bought and sold by the people (because that is one of the ends for which the money is coined); and that the standard weights and measures, fixed by the United States, may be freely used by the people (for that is one of the ends for which the standard of weights and measures was fixed); and that the States can neither forbid the use of the weights and measures, nor the buying or selling of the coin.

The sole object of books is to convey knowledge. If the knowledge cannot be used, of what use are the books themselves?

If a State government can prohibit the use of the knowledge conveyed in a copyrighted book, it might just as well prohibit the buying or reading of the book. The object of the book would be no more defeated in one case than in the other.

This power of “promoting the progress of science and useful arts,” by means of patent and copyright laws, was given to Congress principally, if not solely, because it was feared that the State governments might, in some cases, be unfavorable to that end. But if the States can now prohibit the use of the knowledge conveyed by books, they have that very power of obstructing Edition: current; Page: [19] “the progress of science and useful arts,” which the Constitution intended to take from them.

Furthermore, it is the theory of the courts that the nation purchases the ideas of authors and inventors; that it purchases them solely for the use of the people; and that it pays authors and inventors for their ideas, by giving them certain exclusive rights over them for a term of years.* By this theory, the ideas themselves are supposed to become the property of the nation, from the times when the patents or copyrights are granted; or from the times when the ideas are put upon the government records, in the patent office, or elsewhere. Now, suppose the United States government had been authorized, by the Constitution, to purchase the same ideas, and pay the money for them, instead of paying for them by giving the authors and inventors certain monoplies in the use of them. Could a State, in that case, have prohibited the practical use of the ideas, which the government had thus bought, and paid the nation’s money for, solely for the use of the people? Clearly not. Suppose the United States government had been authorized (by the Constitution) to buy, and pay the money for, Morse’s invention of the telegraph, for the use of the people. Could a State have prohibited Edition: current; Page: [20] the use of the invention, which the nation had thus bought for the use of the people, and paid the people’s money for? Certainly not.

Suppose the United States government (being authorized by the Constitution), had bought books on agriculture, for the use of the people, and paid the nation’s money for them—(instead of paying for them by copyrights, as it does now)—books on the chemical nature and treatment of soils, books on the various plants which the people wish to cultivate, and the various animals which the people wish to rear. Could a State have forbidden the people to read those books? Or to practically apply the knowledge conveyed by them? Clearly not. The idea would be preposterous. The principle that the United States Constitution, in securing to the people those means of agricultural progress, had, by necessary implication, secured to them the right to use those means against all interference by the States, would have been a complete answer to any such pretence on the part of the States.

We might as well say that a State has a right to forbid the people to use the post office, which the United States government has provided for their benefit, as to say that a State has a right to forbid the people to use any “science or useful art,” which the United States government has bought for their benefit.

Any other principle than this would authorize the States to prohibit the practical use of all ideas patented and copyrighted by the United States; and thus utterly defeat the power given to Congress “to promote the progress of science and useful arts,” by means of patents and copyright laws.

It is to be borne in mind that the people of a single State are not the only ones interested in the practical use of patented and copyrighted ideas within that State.

If, for example, the cotton growing States were to prohibit the use of Whitney’s patented cotton gin within those States, the people of all the other States, that manufacture or wear cotton goods, would be made the poorer by the act. If Louisiana were Edition: current; Page: [21] to prohibit the use of Fulton’s patented steamboat within her limits, a great blow would be struck at the commerce and industry of the whole Mississippi valley. If Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin, were to prohibit the use of McCormick’s patented reaper within those States, the price of grain would be affected throughout the whole country. If Massachusetts were to prohibit the use of patented sewing machines, the prices of boots, shoes, and all other clothing, manufactured within the State, for the people of other States, would be enhanced. If New York were to prohibit the use of Hoe’s patented printing press within that State, all the commercial intelligence that radiates from the city of New York, would be delayed, and made more expensive; and the commerce of the whole country would be injured. For these reasons no State can be permitted to prohibit, within her limits, the use of any of the “sciences and useful arts,” which may be patented or copyrighted by the United States.

The same reasons apply to currency. If New York, for example, were to prohibit all but a metallic currency within her limits, the commerce of the whole country, so far as it is carried on within the city or State of New York, would be disturbed, obstructed, and injured. The industry of the whole country would be discouraged to a corresponding degree; and the whole country would be made the poorer. On the other hand, if the best systems of credit and currency, that can be invented, are allowed free course in the city and State of New York, that city and State can do very much, by the use of such credit and currency, to facilitate the commerce, and consequently to develop the industry, of every State in the Union. Even, therefore, if it were admitted that the State of New York might deprive her own citizens of useful inventions in currency and credit, it cannot be permitted to her to dictate in regard to the currency and credit used in the commerce of the whole country within her limits. She is not an independent nation in regard to commerce; and consequently not in regard to credit or currency.

Edition: current; Page: [22]The principle of the United States Constitution, in regard to ideas patented and copyrighted, or in regard to “the progress of science and useful arts,” is, that authors, inventors, and people, shall have the free right to experiment with, and practically test, all ideas for themselves, without asking permission of the several State legislatures. It presumes that they (authors, inventors, and people) are competent to determine, after experiment, what inventions are practically valuable to them, and what worthless.

How preposterous would be the principle—as a political or economical one—that all the ideas, which authors and inventors may originate, in “science and useful arts,” must be submitted to, and approved by, the several State legislatures, (who are utterly incompetent to judge of either their truth or utility,) before the authors and inventors can be permitted to demonstrate their truth or utility to the people, or the people be permitted to adopt them. Such a principle would be manifestly absurd, ridiculous, destructive of men’s natural rights, and destructive of all “progress in science and useful arts.” It would be a tyranny that no people on earth could endure. On such a principle, not even an almanac could be published, or a new rat trap used, within any State, until the legislature of the State should have solemnly sat upon it, and given it the sanction of their profound wisdom, or profound ignorance. If any thing of this nature were to be tolerated in this country, it would plainly be most proper and expedient that Congress, as the legislature for the whole country, should take the matter in hand, and decide, for the whole country, upon the truth and utility of all new ideas offered for public adoption; instead of referring them to the several State legislatures. But Congress knows that they are utterly incompetent to any such task; and, therefore, they leave the whole matter—as the Constitution intended they should—to be determined by the authors, inventors, and people interested. And if this is the principle of the Constitution in regard to all other ideas in “science and useful arts,” it is equally the principle of the Constitution in regard to currency (other than legal Edition: current; Page: [23] tender) and credit; for the Constitution makes no discrimination between inventions and ideas on these latter subjects, and those in relation to other matters (as we shall more fully see in subsequent chapters). The Constitution knows but one law for all new ideas in “science and useful arts.” And that law is that authors and inventors may come freely face to face with the people, and test all ideas to their mutual satisfaction; leaving the people free to adopt or reject at their own discretion.