The Collected Works of Lysander Spooner (1808-1887)

|

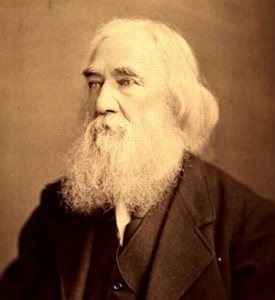

Lysander Spooner (1808-1887) was a legal theorist, abolitionist, and radical individualist who started his own mail company in order to challenge the monopoly held by the US government. He wrote on the constitutionality of slavery, natural law, trial by jury, how binding was the authority of the US Constitution over individuals, intellectual property, paper currency, and banking.

A full list of his Collected Works in both chronological order of date of publication (useful for seeing how his interests and ideas changed over time) and a thematic list by topic can be found here. The numbers refer to the work’s place in the chronological order.

More information about Spooner and his work:

- Spooner's main bio page: </people/4664>.

- School of Thought: Abolition of Slavery </collections/33>.

- School of Thought: 19th Century Natural Rights Theorists </collections/38>.

The Second Edition

We began (2009-10) putting Spooner's works online book by book and pamphlet by pamphlet over a period of several years. The second edition of his Works will be 5 volumes in chronological order by date of publication. The works will be available temporarily here in HTML. They can be found in facsimile PDF here as well:

The Collected Works of Lysander Spooner (1834-1886), in 5 volumes (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2015).

- Vol. 1 (1834-1850) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner-1> or PDF </titles/2294>.

- Vol. 2 (1853-1855) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner-2> or PDF </titles/2295>.

- Vol. 3 (1858-1862) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner-3> or PDF </titles/2296>.

- Vol. 4 (1863-1873) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner-4> or PDF </titles/2297>.

- Vol. 5 (1875-1886) - HTML </pages/works-of-spooner-5> or PDF </titles/2298>.

The entire works of Spooner are searchable from the main bio page </people/4664>.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

The texts are in the public domain.

This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Table of Contents

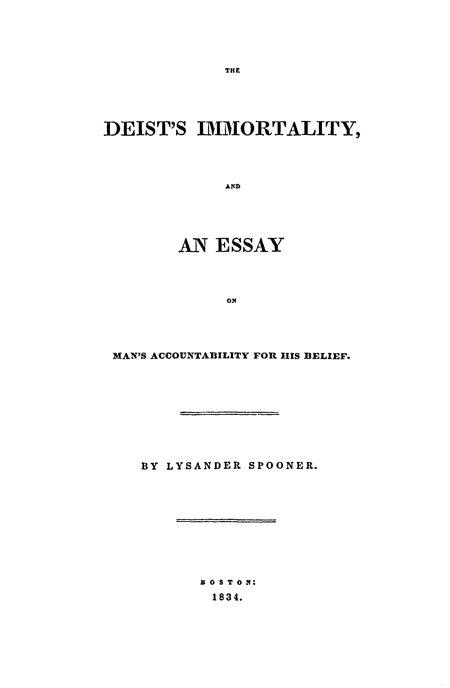

- T.1 The Deist's Immortality, and an Essay on Man's Accountability for his Belief (1834).

- T.2 "To the Members of the Legislature of Massachusetts" (August 26, 1835).

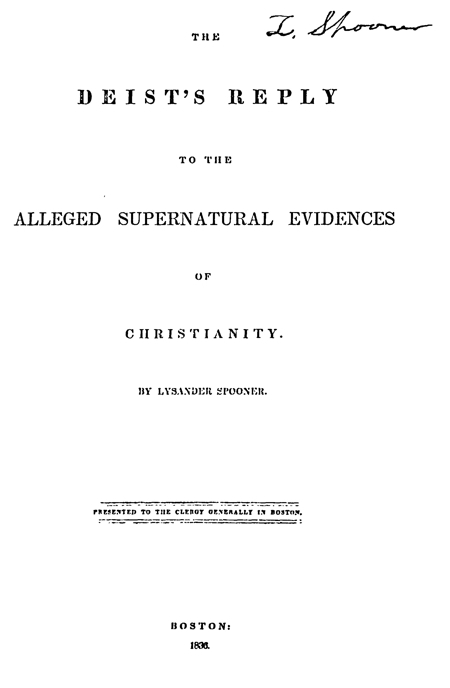

- T.3 The Deist's Reply to the Alleged Supernatural Evidences of Christianity (1836).

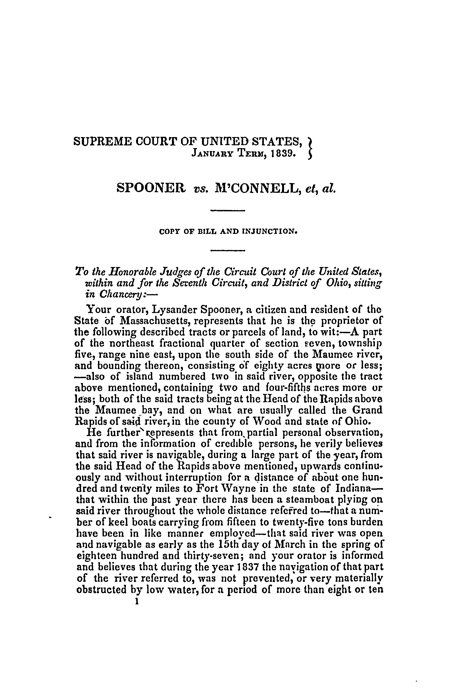

- T.4 Supreme Court of United States, January Term, 1839. Spooner vs. M'Connell, et al. 1839).

- T.5 Constitutional Law, relative to Credit, Currency, and Banking ( 1843).

- T.6 The Unconstitutionality of the Laws of Congress, Prohibiting Private Mails ( 1844).

- T.7 Poverty: its Illegal Causes and Legal Cure. Part First. (1846).

- T.8 Who caused the Reduction of Postage? Ought he to be Paid? (1850).

- T.9 Illegality of the Trial of John W. Webster 1850).

- T.10 A Defence for Fugitive Slaves, against the Acts of Congress (1850).

- T.11 An Essay on the Trial by Jury (1852).

- T.12 The Law of Intellectual Property; or An Essay on the Right of Authors and Inventors to a Perpetual Property in their Ideas (1855).

- T.13 A Plan for the Abolition of Slavery, and To the Non-Slaveholders of the South (1858).

- T.14 Address of the Free Constitutionalists to the People of the United States (1860).

- T.15 The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1860).

- T.16 The Unconstitutionality of Slavery: Part Second 1860).

- T.17 A New System of Paper Currency (1861).

- T.18 Our Mechanical Industry, as Affected by our Present Currency System: An Argument for the Author’s “New System of Paper Currency” (1862).

- T.19 Articles of Association of the Spooner Copyright Company for Massachusetts (1863).

- T.20 Considerations for Bankers, and Holders of United States Bonds (1864).

- T.21 A Letter to Charles Sumner (1864).

- T.22 No Treason, No. 1 (1867).

- T.23 No Treason. No II.The Constitution (1867).

- T.24 Senate-No. 824. Thomas Drew vs. John M. Clark (1869).

- T.25 No Treason. No VI. The Constitution of No Authority (1870).

- T.26 A New Banking System: The Needful Capital for Rebuilding the Burnt District (1873).

- T.27 Vices are Not Crimes: A Vindication of Moral Liberty (1875).

- T.28 Our Financiers: Their Ignorance, Usurpations, and Frauds (1877).

- T.29 The Law of Prices: A Demonstration of the Necessity for an Indefinite Increase of Money (1877).

- T.30 Gold and Silver as Standards of Value: The Flagrant Cheat in Regard to Them (1878).

- T.31 Universal Wealth shown to be Easily Attainable. Part First (1879).

- T.32 No. 1. Revolution: The only Remedy for the Oppressed Classes of Ireland, England, and Other Parts of the British Empire (1880).

- T.33 Natural Law; or the Science of Justice (1882).

- T.34 A Letter to Thomas F. Bayard: Challenging his Right - and that of all the Other Socalled Senators and Representatives in Congress - to Exercise any Legislative Power whatever over the People of the United States (1882).

- T.35 A Letter to Scientists and Inventors, on the Science of Justice, and their Right of Perpetual Property in their Discoveries and Inventions (1884).

- T.36 A Letter to Grover Cleveland, on his False Inaugural Address, the Usurpations and Crimes of Lawmakers and Judges, and the Consequent Poverty, Ignorance, and Servitude of the People (1886).

T.1.The Deist's Immortality, and an Essay on Man's Accountability for his Belief (1834).↩

Title

[1.] The Deist's Immortality, and an Essay on Man's Accountability for his Belief (Boston, 1834).

- also online Shorter Works, vol. 1: </titles/2290#lf1531-01_head_002>

Text

the DEIST’S IMMORTALITY, and AN onMAN’S ACCOUNTABILITY FOR HIS BELIEF.

THE DEIST’S IMMORTALITY.

Deists are led to believe in a future existence, by the consideration, that, without it, our present one would seem to be without aim, end or purpose. As a work of Deity it would appear contemptible. Whereas, by supposing a future life, we can imagine, in our creation, a design worthy of Deity, viz. to make us finally elevated intellectual and moral beings.

They are led to this belief by the further facts, that our natures appear to have been specially filted for an eternal intellectual and moral advancement; that we are here surrounded by means promotive of that end; and that the principal tendency of the education and impressions, which our minds here receive from the observation and experience of what exists and takes place in this world, is to carry them forward in that progress.

Again,—we are gifted with a desire of knowledge, which is stimulated, rather than satisfied, by acquisition. We are here placed in the midst of objects of inquiry, which meet that desire; and there is still an unexplored physical, mental and moral creation around us. Here then are supplied the means of our further intellectual growth. We are also the constant witnesses of actions, objects and occurrences, which call into exercise our moral feelings, and thus tend to to improve our moral susceptibilities and characters. Analogy, and all we know of nature, support the supposition, that, if we were to continue our existence in the universe, of which this world is a part, we should always be witnesses of more or fewer actions, objects and occurrences similar to these in kind. Here too then we may see evidence of means and measures provided and adopted for our future moral culture. Our natures therefore are capable of being eternally carried nearer and nearer to perfection solely by the power of causes, which we see to be already in operation. The inquiry therefore is a natural one—what means this seeming arrangement? Does it all mean nothing? Is a scheme capable of such an issue as our creation appears to be, and for the prosecution of which every thing seems prepared and designed, likely to be abandoned, by its author, at its commencement? If not, then is the evidence reasonable, that man lives hereafter.

This evidence too is direct; it applies clearly to the case; it is based on unequivocal facts, such as have been named; it is not secondary; it does not, like that on which Christians rely, depend upon the truth of something else which is doubtful.

An argument against the probability that this theory of Gods intention to carry men on in an intellectual and moral progress, will be executed in relation to all mankind, [4] has been drawn from the fact that many appear to have chosen, in this world, a path opposite to “this bright one towards perfection;” and it is said to be reasonable to suppose that they will always continue in that opposite course. Answer—There is, in every rational being, a moral sense, or reveerence for right. This seminal principle of an exalted character never, in this world, becomes extinct; it survives through vice, degradation and crime: it sometimes seems almost to have been conquered, but it never dies; and often, even in this world, like a phenix from her ashes, it lifts itself from the degradation of sensual pollution under which it was buried, and assumes a beauty and a power before unknown. How many, whose virtuous principles had been apparently subdued by temptation, appetite and passion, have suddenly risen with an energy worthy an immortal spirit, shaken off the influences that were degrading them, resisted and overcome the power that was prostrating them, become more resolutely virtuous than ever, and had their determination made strong by a recurrence to the scenes they had passed. This has happened in multitudes of instances in this world.

It should be remembered that nearly or entirely all our errors and wanderings from virtue here, proceed from the temptations offered to our appetites and passions by the things and circumstances of this world. The sensual indulgences, which follow these temptations, at length acquire over many a power, which, while exposed to those temptations, they would probably never shake off. But here we see the beneficent interference of our Creator, for when we are removed from this world, we are removed also from the influence of those particular temptations, which have here mastered us. We have then (without supposing any thing unnatural or improbable) apparently an opportunity to set out on a new existence—released from those seductions, which had before proved too strong for our principles—having also the benefit of past experience to warn us against the temptations which may then be around us, and inspired by a more clear developement of the glorious destiny ordained to us.

If many have chosen and resolutely entered upon a course of virtue while in this world, and while exposed to all the temptations which had once acquired a power over them, is it not natural to suppose that the opportunity offered to men by an exchange of worlds, will be embraced by all whose experience shall have shewn them the weakness, unhappiness and degradation of a course opposite to that of virtue?

But since many are removed from this life before their moral purposes are decided by their observation and experience of evil, may we not suppose, that, to effect that object in such, and to strengthen those purposes in all, enticements and temptations will be around us in the next stage of our existence? And who knows whether, if those temptations should ever become too strong for our virtue, the same [5] measure of removal may not be repeated again and again in our progress—at each advance, a new and wider horizon of God’s works, and a more extensive developement of his plans, opening before, and corresponding to, our enlarged and growing faculties—our intellectual and moral powers nourished and expanded by such new exhibitions of his wisdom, benevolence and power, as shall excite new inquiries into the principles, measures and objects of his moral government, and call forth higher admiration, and purer adoration, of his greatness and goodness? Was ever a thought more full of sublimity? A thought representing all rational beings as possessing the elements of great and noble natures, capable of being, and destined to be, developed without limit—a thought representing Deity, in the far future, as presiding over, not merely an universe of matter, or such limited intellects as ours are at their departure from this world; but as ruling over, occupying the thoughts, and inspiring the homage, of a universe of intelligences intellectually and morally exalted, and constantly being exalted, towards a state high and perfect beyond our present powers of conception.

Compared with these views and prospects, how puerile is the heaven of Christians—how enervating to the mind their languishing and dreamy longings after a monotonous and unnatural bliss. Many of them do indeed believe in the eternal progress of the soul—but they obtain not this belief from the Bible. It was the much scoffed at theology of reason and nature, that taught to them this doctrine, which is, above all others connected with the future, valuable to man while here, and honorable to Deity.

The impression, made by the representations of the Bible, is, that men are removed from this world to a state, in which their intellectual faculties will always remain the same as they were immediately after their entrance thither. They are there represented as eternally praising Deity for a single act, viz. their redemption—an act, which, if it could be real, could have been performed only in favor of a part of the human race, and which could, neither from any extraordinary condescension, benevolence or greatness in the act, entitle Deity to an homage in any degree proportionate to what he would be entitled to, if the theology of reason, on this point, instead of the theology of Christianity, be true.

How absurd too is it to suppose that Deity, who must be supposed to have willed the existence of our homage towards him, should will only that which should spring from so scanty a knowledge of his designs, and which should be offered by intellects so incapable of appreciating his character, as Christianity contemplates.

Finally the Christian’s heaven is an impracticable one, unless God shall perform an eternal miracle to make it otherwise. The nature of our minds is such that they cannot always dwell upon, and take pleasure in, the same thought or object, however glorious or delightful it may be in itself.—There [6] is in them an ever-restless desire of change, and of new objects of investigation and contemplation, and it is by the operation of this principle that our eternal intellectual advancement is to be carried on. But Christianity offers to us, in its promised heaven, one prominent subject only of reflection and interest—a subject, which, if it were real, although calculated perhaps to excite gratitude for a time, could never, without the aid of a miracle, operate upon our present natures so as to produce an eternal delight.

But it will probably be said that our natures will be so changed, as to be fitted to forever receive pleasure from the same source. Answer 1st. Such a change would be a degradation of our present natures, and that we cannot believe that Deity would ever cause. Answer 2d. If our natures are to be so essentially changed as always to rest satisfied with one subject of contemplation, to always receive their highest and constant pleasure from one fountain, and to have their intellectual thirst forever quenched, we should not then be the same beings that we were. Answer 3d. Such a change in, or rather annihilation of, our mental appetites, is inconsistent with our further progress, because the principle, which is to urge us on, will then be removed—therefore a belief in the Christian’s heaven is inconsistent with a belief in the eternal progress of the soul.

The theory of successive existences is rendered probable, by the obvious necessity of having our situations, and the objects of investigation and reflection, by which we are to be surrounded, correspond to the state of our capacities. The same condition, which, like this world, is suited to the infancy of our being, would not be best adapted to the improvement of one who had existed for a series of ages.

Further—it is difficult to account for the temporary character of our present existence, otherwise than by supposing it the first of a series of existences. The idea that it was intended as a state of probation is one of the most absurd that ever entered the brains of men. It is absurd, in the first place, because the fact, that so large a portion of mankind are removed from it before their characters have been determined by influences calculated to try them, is direct evidence from Deity himself that he did not intend it for that purpose; and, in the second place, it is absurd, because the utility of a state of probation is not the most obvious thing in the world, when it is considered that the consequence of one is admitted to be, that a part of mankind become eternally miserable and wicked, whereas, without one, it must be admitted that all might become such beings as I have previously supposed them designed to be.

AN ESSAY, ON MAN’S

The Bible threatens everlasting punishment to such as do not believe it to be true—or to such as do not believe that a certain man, who grew up in the town of Nazareth, was a Son of the Almighty! Is it just to punish men for not thinking that true, which is improbable almost beyond a parallel? If not, the Bible defames the character of Deity by charging him with such conduct.

Is our belief an act of the will? If it were, the threat might operate as a motive to induce us to believe, or to persuade us to make up our minds that we would believe. But no one pretends that a man can believe and disbelieve a doctrine, or think it true and false, whenever occasion seems to require.

Our minds are so constituted that they are convinced by evidence. Sometimes too they believe a thing, and in perfect sincerity too, without being acquainted with any real evidence in favor of its truth. Such a belief comes naturally of the impressions, which the minds of some persons receive from the circumstance that the thing is generally believed by others with whom they are acquainted, or from the fact that it has long been believed by others. These circumstances, although they can hardly be considered as evidence, yet have the effect of evidence in satisfying many. There is a fashion in religion, by which men’s minds are carried away. We may see it every where. Such, it will by admitted on all hands, is the case in Pagan countries, and it is also more or less the case in civilized and enlightened nations. Although the evidence of Mahomet’s having been a Prophet of God, is probably insufficient to convince any enlightened, impartial mind, possessed of common strength, still, it entirely satisfies the mind of a Turk of the strongest intellect. The reason is, that the little real evidence is aided in its influences by the associations and impressions of his whole life.

When the mind is thus completely satisfied of the truth of a thing, is there any obligation of morality, which requires a man to look farther? If it were so, men could never safely come to a conclusion on any subject; it would be their duty never to consider any thing to be settled as true. But God has so constituted our minds that when they are convinced, they rest satisfied until their doubts are excited by opposite evidence or impressions. Until then it is not in the power of man to doubt. If therefore there be any moral wrong in resting satisfied in a belief, of which the mind is convinced, there is no alternative but to say that God, by having so constituted our minds, has made himself the author of that wrong.

One, who is entirely satisfied of the truth of a matter, although he be in reality mistaken, feels no moral obligation [8] to inquire further into its evidences, and, of course, violates no moral obligation by not inquiring—therefore he cannot be morally guilty. In such an instance, if there were any wrong on the part of any one, it could be only on the part of God for having so constituted the individual, as that, in such a case, he would have no moral sense to direct him aright.

It is only when a man’s doubts are excited, that his moral sense directs him to investigate. Supposing then a Pagan or Mahometan were to feel entirely satisfied that his system were true, is there any moral obligation resting upon him to spend his time in inquiring into other systems? Is he not acting uprightly in considering his faith as certain until his doubts are excited? Is it then just to punish him? If not, then Jesus could never have been authorized by Deity, in the manner he imagined, to threaten punishment to such an one on account of his belief.

It is so likewise, when men are entirely convinced that a narrative, for example, is untrue—they have then no moral sense that commands them to inquire into its evidences, and, of course, do not violate their moral sense in not inquiring. Christians feel no moral obligation to investigate the evidences of Mahometanism, because, without any investigation, they are convinced that it is untrue. Mahometans are in the like condition in respect to Christianity; and whether Christianity, or Mahometanism, or neither, be true, the Mahometan is as innocent on this point as the Christian.

If a man read the narratives of the miracles said to have been performed by Jesus, and his mind be perfectly convinced that the evidence is insufficient to sustain the truth of such incredible facts, his moral sense does not require him to go farther—it acquits him in refusing his assent. So if he be not entirely satisfied, and his moral sense dictate further investigation, and he then make all which he thinks affords any reasonable prospect of enlightening him, and his mind then become entirely convinced of the same fact as before, his conscience is satisfied, and he is innocent.

How many have done this, and have become Deists. We have the strongest evidence too, that, in their investigations, no unreasonable prejudice against Christianity has operated upon their minds. Vast numbers of men, living in Christian countries, where it was esteemed opprobious to disbelieve Christianity—men, whose parents, friends and countrymen were generally Christians, and whose worldly interest, love of reputation, love of influence, and even the desire of having bare justice done to their characters, must all have naturally and strongly urged them to be Christians; and whose early religious associations were all connected with the Bible—men, too, of honest, strong and sober minds, of pure lives and religious habits of thought, have read the Bible, have read it carefully and coolly, have patiently examined its collateral evidence, and have declared that they were entirely convinced that it was not what it pretended to be—that [9] the evidence against it appeared to them irresistible, and that by it the faintest shadows of doubt were driven from their minds. Their consciences rest satisfied with this conclusion—their moral perceptions tell them that their conduct in this matter has been upright—they know, as absolutely as men can know any thing of the kind, that if they are in an error, it is an error, not of intention, but of judgment, not of the heart, but the head; and yet the sentence of the Bible against such men is, “the smoke of your torments shall ascend up forever and ever!” The enormity of the punishment, and the monstrousness of the doctrine, are paralleled by each other, but are paralleled by no doctrine out of the Bible, in which enlightened Christians believe. Men can hardly be guilty of greater blasphemy than to say that this doctrine is true. And yet the Bible employs these unrighteous and fiend-like threats, to drive men to believe, or to close their minds against evidence lest they should disbelieve, narratives and doctrines as independent of, and as unimportant to, religion and morality, as are the histories of Cæsar and Napoleon—narratives, which set probability at defiance, and doctrines, which do injustice to the characters of God and men.

Many Christians say the reason, why men do not believe the Bible, is, that they do not examine it with an humble mind—and an humble mind, as they understand it, is one which has prepared itself, as far as it is able, by prayers, and fears, and a distrust of its own ability to judge of the truth of what it ought to believe, to surrender its judgment, to suppress its reasonings, to banish its doubts, and then believe the Bible on mere assumption, in spite of the incredibility of its narratives, the enormity, impiety and absurdity of its doctrines, and the contemptible character of its evidences.

They are accustomed to say that the doctrines of the Bible are too humiliating for the pride of men to acknowledge. But Deists acknowledge as strong religious obligations, and as pure moral ones, as Christians. As for the humiliation of believing Christianity, there certainly is nothing more humiliating in believing that Jesus performed miracles, or that he was prophesied of before his coming, than there is in believing any other fact whatever. If it be humiliating to believe one’s self that wicked animal, which the Bible represents man to be, it is because it is contrary to nature and reason to be willing to consider ourselves wretches worthy of all detestation, especially when our own knowledge of the moral character of our intentions gives the lie direct to any such supposition. Every human being knows, or may know, if he will but reflect upon the motives which have governed him, that he never in his life performed a wrong act simply from a desire to do wrong. No man loves vice, because it is vice, although many strongly love the pleasure which it sometimes affords. Men are induced to wrong actions by a variety of motives, and desires, but the simple desire to do [10] wrong never inhabited the breast, or controlled the conduct, of any individual. Yet in order to prove that men’s natures are in the slightest degree intrinsically and positively wicked, it is necessary to prove that individuals are, at least, sometimes, influenced by a special desire of doing wrong. To prove that men are led, by any other desires, to commit wrong actions, only proves the natural strength of those desires, and the comparative weakness of their virtuous principles, or, in other words, it proves the imperfect balance of their propensities and principles—an imperfection, which, of course, ought to be guarded against, because it often leads men to do wrong, and which may need, though not deserve, the admonitory chastisement which God applies to men—but it does not prove any positive wickedness of the heart. So that, even if a man were (as no man ever was) entirely destitute of all regard to right, still, if he had not any special desire of doing wrong, whatever other desires he might have, and to whatever wrong conduct they might lead him, he would nevertheless be intrinsically only a sort of moral negative—he would not be at heart positively wicked.

But the very reverse of the doctrine of intrinsic wickedness is true of every man living, for every man’s character is more or less positively good—that is, he has some regard to right—and that regard is as inconsistent with wickedness of heart, or a desire to do wrong, as love is with dislike.—In a large portion of mankind, this regard to right is one of their cardinal principles of action, and shows itself to be too strong to be overcome by any but an unusual impulse or temptation. Now is a man, who, as far as he knows, and as far as he thinks, means to do right, whose general intentions are good, and who is generally on his guard lest he should do wrong, to stultify his intellect, and discredit the experience of his whole life, in order to believe a book, written two thousand years ago, in scraps by various individuals, and whose parts were collected and put together like patchwork, when it tells him that he is a “desperately wicked,” depraved and corrupt villain? A man might as well tell me that I do not know the colour of my own skin, or the features of my own face, as that I do not know the moral character of my own intentions, or, (if theologians like the term better,) of my heart—and he might as well tell me that my skin is black, or my eyes green, as that my inclination is to do wrong, or that my heart is bad. He would not, in the former case, contradict my most positive knowledge any more directly than in the latter.

Were I to say that all men’s bodies were corrupt and loathsome, every one would call me a person who had been in some way so far deluded (and what greater delusion can there be?) as that I would not believe the evidence of my own senses. Yet, had I always been told by my parents, my friends, and by every one about me, and had I read in a book, which I believed to be the word of God, from my earliest [11] years, that such was the fact, and that corporal substances were above all things deceitful, there can be no doubt that I should have partially believed it now, or, at least, during my childhood and youth. Still, my senses, and my experience do not more clearly disprove that fact, than they do that men’s hearts or intentions are intrinsically wicked. But Christians believe the contrary, and simply because it has been dinging in their ears from their childhood; because they have habitually read it in what they supposed the word of God, from a period prior to the time when they were capable of judging of men’s characters; because they have thus been taught to attribute every wrong action of men to the deplorable wickedness of their hearts; and because they have been taught to consider it a virtue to look upon their own and others’ characters, through the dingy medium of the Bible.

The humiliation therefore of believing the Bible, is principally the humiliation of believing a detestable falsehood for the sake of holding one’s self in abhorrence—an humiliation calculated to destroy that self respect, which is one of the strongest safeguards of virtuous principles—an humiliation, to which no person ought to submit, but into which many of the young, the amiable and the innocent have been literally driven.

Again. The facts, that many honest, enlightened and religious men have disbelieved Christianity; that many, who saw the supposed miracles, disbelieved it;* that the inconsistencies of the Bible have given rise to hundreds of different systems of religion; that every sect of the present day, in order to support its creed, is obliged to deny the plain and obvious meaning of portions of the Bible; and that the truth or importance of almost every theological doctrine contained in it is denied by one sect or another, which professes to believe in the inspiration of the book itself, if they are not proof that this pretended light from God is but the lurid lamp of superstition, are, at least, sufficient evidences that a man may reasonably disbelieve it to be what it pretends to be, viz. a special revelation of luminous truth. But is it credible that Deity has made to men a communication, on a belief or disbelief in which, he has made their eternal happiness or misery to depend, and yet that he has made such an one, and has made it in such a manner, that men may reasonably disbelieve it to be genuine?

Even if we attribute men’s unbelief to the perverseness of their dispositions, still, the greatest of sinners are the very ones whom this system professes to be more especially intended to save—and would these then be left unconvinced? How absurd is it to suppose that Deity would go so far as to violate the order of nature in order to save men of perverse minds by bringing them to a knowledge of the truth, and [12] that he should then fail of doing it by reason of the very obstacle, which he had undertaken to remove. To say that he has done all in his power to convince men, is to say, that, in a comparatively momentary period from their birth, minds of his creation have become too powerful for him to control. To say that he has not done all in his power, is to attribute to him the absurdity of adopting means for the purpose of accomplishing the greatest object (in relation to this world) of his moral government, when he must have been perfectly aware that those means would be insufficient.

Is it credible that, if God have made to men a communication, on a belief in which depends all their future welfare, he would have interlarded it with so much that is disgusting and improbable, as that the whole would be disbelieved, rejected and trodden underfoot, by well-meaning men? On the contrary, would he not have made is so probable as to have carried conviction to every mind that could be benefitted by it? Was he not bound by every principle of parental obligation to have made it self evidently true? Ought he not, when such tremendous consequences were at stake, and if need there were, to have written this communication over the whole heavens, in letters of light, and in language that could not be misinterpreted, that man of every age, nation and colour, might rend and never err? Would he not have completely established, in the mind of every accountable being, by a sufficient and immoveable proof, the truth of every syllable essential to their salvation? If he would not, then, according to the best judgment, which the perceptions he has given us will enable us to form, he must be what I will not name.

But this is not all. The Bible requires of a certain portion of mankind, not only, that they believe it a revelution from God, but that they violate their consciences in order to to believe it. For example, by requiring all men, without exception, to believe it or be damned, it requires the believers in the Koran and the Shaster to renounce those books as false. This it is impossible for them to do, unless they first investigate the evidences against their truth. Now, I think no candid man will pretend, either that those believers would not feel as much horror at the supposed impiety of disbelieving those books, as a Christian does at that of disbelieving the Bible, or that it would not require on their part as great a struggle with their consciences to go into the investigation of the evidences against the truth of those books, as it would on the part of the Christian to go into the investigation of the evidences against the truth of the Bible. Yet the Bible, by demanding of them that they believe it, virtually demands that they thus violate their consciences in order to go into such an investigation as is necessary to lead them to disbelieve those systems, which they now revere as too sacred to be doubted; and it demands this of them too on the threatened penalty of eternal damnation.

[13]If there be any conduct more wicked than any other which can be conceived of, that, which is here ascribed to Deity, must, it appears to me, exceed in wickedness any other that the human mind ever contemplated. Its wickedness is, in fact, no less than that of hereafter punishing men through eternity, for not having done in this world that which they most religiously believed to be wrong.

And what is it to believe the Bible, that men should merit the everlasting vengeance of the Almighty for not believing it? Why, setting aside its secondary absurdities and enormities, it is to believe in these giant ones, viz. that when Deity created an universe, in pursuance of a design worthy of himself, he created in that universe a Hell—a Hell for a portion of the beings to whom he was about to give life—a Hell for his children—a Hell that should witness the eternal reign of iniquity, misery and despair—a Hell that should endlessly perpetuate the wickedness and the wo of those who might otherwise have become virtuous and happy; that he then, after having created men, and given them a nature capable of infinite progress in knowledge and virtue, by placing them in a world full of enticement and seduction, deliberately laid the snare, made the occasion, fed the desire, and instigated, invited and seduced to the conduct, which he knew certainly would issue in the moral ruin of that nature, and the endless wretchedness of the individuals: and, finally, that all this was right, that such a Being is a good Being, and that he merits from us no other sentiment than the highest and purest degree of filial and religious emotion.

And what is the evidence, on which we are called upon to believe all this? Why, it is this. Some eighteen hundred years ago, a few simple individuals, from among the most ignorant class, in a most unenlightened, superstitious and deluded community, where a supposed miracle was but an ordinary matter, where miracle-working seems often to have been taken up as a trade, and where a pretended Messiah was to be met, as it were, at every corner, said that they had this story from one of the wandering miracle-working Messiahs of the day, who performed many things, which appeared to them very wonderful; although they admit that these same things, as far as they were seen by others, (and nearly all the important ones, except such as were studiously concealed, were seen by others,) did not, to those others, appear very wonderful or unusual. They also expressly admit that, of those who had once been induced to follow him, nearly all very soon changed their minds in relation to him, and deserted him. They also, by themselves deserting him when he was apprehended, virtually acknowledge that their own confidence in him had then gone to the winds, and would never have returned, had it not been, that, after having submitted to a part of the usual forms of an execution, and being taken down for dead, (at three o’clock or later in the afternoon,) he, as soon, at the farthest, as the next night [14] but one, (not “three days” after, be it remarked) and how much sooner we know not, returned to life, (as men are very apt to do who have been but partially executed,) and had the extraordinary courage to lurk about for several days, and shew himself, not openly to the world, but in the evening, and within closed doors, to some dozen who had before been his very particular friends. This is altogether the strongest and most material part of the evidence in the case,* and the question, which arises in relation to it, is, whether it be sufficient to sustain such an impeachment, as has been alluded to, of the character of the Almighty?—A question, which, if the march of mind continue, men will sometime be competent to settle.

John 12-37—“But though he had done so many miracles before them, yet they believed not on him.”

It will be recollected that no one of the twelve ever speak of having witnessed, or heard of, any ascent into heaven.

T.2 "To the Members of the Legislature of Massachusetts" (August 26, 1835).↩

Title

[2.] "To the Members of the Legislature of Massachusetts." Worcester Republican. - Extra. August 26, 1835.

- also online Shorter Works, vol. 1: </titles/2290#lf1531-01_head_005>

Text

WORCESTER REPUBLICAN.—EXTRA.

WORCESTER, WEDNESDAY AUGUST 26, 1835.

TO THE MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATURE OF MASSACHUSETTS.

Gentlemen, I feel personally interested to procure a change in the laws relating to the admission of Attorneys to the Bar; and since no one, unless he be thus personally interested, will be likely ever to take the trouble thoroughly to inquire into, or fully to expose the injustice and absurdity of the restraints now in force, I take the liberty of addressing and sending to you this letter, and respectfully asking your consideration of the subject.

By the Statute of 1792 Ch. 4, establishing the Supreme Judicial Court, it is provided (See. 4) that said Court “shall and may, from time to time, make, record and establish all such rules and regulations with respect to the admission of Attorneys ordinarily practising in the said Court, and the creating of barristers at law, as the discretion of the same Court shall dictate—provided that such rules and regulations be not repugnant to the laws of the Commonwealth.”

Pursuant to this authority, the Supreme Judicial Court have established such rules (see Bigelow’s Digest—Title, Counsellors and Attorneys,) that it is now necessary for a graduate to spend three years, and a non-graduate five years, in the study of the law, before he can be admitted to practise in the Common Pleas, and then to practise four years in the Common Pleas before he can be admitted a Counsellor of the Supreme Court.

These rules, as to the time of study, are peremptory—and the custom is, (whether the rules contemplated it or not,) after this time has been nominally passed in study, whether it really have been passed in study or in idleness, to admit the applicant as a matter of course, without any further inquiry as to his attainments. It is true that the persons, with whom he has studied, certify that he has been “diligent” in the pursuit of the education proper for his profession—but this certificate is no evidence that such has been the fact, and is not so considered by the Bar, because it is given, and is understood to be given, indiscriminately as well to those who have been grossly and notoriously negligent, as to those who have been diligent. So that, in fact, the time and money, expended in nominally preparing for the profession, and not the acquirements or capacity of the candidate, constitute the real criterion, by which he is tried when he applies for admission.

The Bar in this (Worcester) County, and I suppose also in the other Counties, have improved, in letter if not in spirit, upon the unjust and arbitrary character of the rules of the Court. The 12th of the Rules of the Bar in this County is in these words. “No Student shall commence, or defend any action, or do any other professional business on his own account; and no Student shall be employed for pay, in any business for himself.” And the Bar have substantially the power to prevent the admission of any one, who shall infringe this rule; because the Court will not take upon itself to admit any one, who is not recommended by the Bar, unless the Bar shall “unreasonably refuse to recommend” him, (Rule 7th of S. J. C. See Bigelow’s Digest, as before—also Rule 6th C. P. See Howe’s Practice—appendix,) and it probably would not consider the conduct of the Bar, in refusing to recommend one, who had spent a part of his noviciate in earning his subsistence, unreasonable. The Court would undoubtedly say that the spirit of their own rule required that the Student’s exclusive business, during his noviciate, should be the acquisition of the necessary qualification, for his profession.

Although we have the evidence of experience, yet we need it not, in order to demonstrate that it must be a necessary operation of these rules, to exclude from the profession a class of young men, who, as a general rule, would be more likely to excel in it than any other—I mean the well-educated poor. I say this class would be more likely to excel in it than any other, because they generally do excel all others in whatever they undertake, that requires energy and perseverance. The access of this class to the profession, and their success in it, are made, by these rules, actually impracticable. In the first place, if they have the perseverance to go through the extreme and long continued toil and exertion, that must be gone through, if they would defray, as fast as they accrue, the expenses of so long a course of preparatory studies as are now required, they must, of necessity, by that time have exhausted, in a great degree, the energies, that are indispensable to success in the laborious profession of the law; because it is not in human nature that a man should acquire, and at the same time earn the money to pay for, so expensive and long a course of education, and retain his energy fresh and unbroken. He must also, even after he has made all this effort, be so far advanced in life, that he must enter the profession under great disadvantages on account of his age, and must be little short of insane to imagine that, with his wasted powers, he can then set out and compete with those who commenced fresh and young.

Take another case—that of a poor young man, who may be (what few can ever hope to be) fortunate enough to obtain credit and assistance, while getting his education, on the condition that he shall repay after he shall have engaged in his profession—so long is the term of study required, and such is the prohibition upon his attempts to earn any thing in the mean time for his support, that he must then come into practice with such an accumulation of debt upon him as the professional prospects of few or none can justify. Experience has shown the result to be what any one might have foreseen that it would be. The class of young men, before mentioned, the well-educated poor, have been, almost without a solitary exception, excluded from the profession, which many of them would have chosen and adorned, had it been open to them, and have been actually driven into other pursuits—and the profession is now filled, with few exceptions, by men, who were educated in comparative ease and plenty; who have neither the capacity nor the energy necessary to success; who chose this profession, not because their minds were adapted to it, but because, having received a liberal education, it was necessary that they should choose some profession, whether they were fitted for it, or not.—You, Gentlemen, as well as I, must be aware that as often as one, with the requisite talents for a lawyer and advocate, can be found in the profession, five, if not ten, others can be found in it, who have not these talents—who are in fact palpably incompetent to anything but the minor and almost formal parts of professional business. I think you must also be aware that the present lack of able lawyers is not owing to any scarcity of talent among the people—but is to be attributed solely to the fact, that the laws of the State, and the rules of Courts and Bars are such as operate to admit many, who are unfit for the profession, and to exclude many who are especially fitted to excel in it.

Among the well-educated poor there are many, who have a passion for the profession, who have also an equal talent for it, and at least equal, if not more than equal perseverance, with those few, who now stand at the head of the Bar—and were the access to the profession made as easy as it might be, there cannot be a doubt that in a little time the wants of the whole community would be supplied with lawyers of a grade equal to that of the few able ones, who are now to be found but here and there.

If Attorneys were permitted to practise, and thus to do something for their support as soon as they could qualify themselves for doing the minor business of the profession, few young men of character and talents are so destitute of resources as to be unable to obtain the necessary education—and why is it not as much a man’s right, to avail himself of his earliest ability to earn his living by this employment, as by any other?

I am aware that there is a statute, (1790 Ch. 58,) that provides that any person of decent and good moral character, who shall produce in Court a power of Attorney for that purpose, shall have the power to do whatever an Attorney regularly admitted may do, in the prosecution and management of suits. But if he once commence in this way, he must always continue in it, for the Bar or Court will never admit him afterwards on the strength of any qualifications that he may acquire by practising in this way. (This fact shows how utterly arbitrary and reckless of right are the rules that are made to govern in this matter, and how inveterate is the determination, on the part of this mercenary and aristocratic combination, to exclude, from competition with them, all who are unable to comply with certain conditions, which have no necessary, or (as experience has proved) even general connexion with an individual’s real fitness for the profession.)

It is imposing upon an Attorney, who has any considerable business, a great and unnecessary inconvenience to oblige him always to take from his client, and carry with him a power of Attorney. There is also another objection—the people are unaccustomed to give powers of Attorney in [15a] such cases, and if a practitioner inform them that he must have one, before he proceeds in his cause, they do not exactly understand why it should be necessary—they are afraid there is something in the matter more than they know—the circumstance creates a distrust against the counsel, and is therefore injurious to him.

The change I would propose is this—that a law he passed that any person, above the age of twenty-one years, of decent and good moral character, on making application either to the Common Pleas or Supreme Court for admission as an Attorney, and paying to the Clerk his recording fees be admitted, without further ceremony or expense, to practice in every Court, and before every magistrate in the State, and that he then have the same right, that an admitted Attorney now has, of appearing in actions without a power of Attorney.

I would, however, have in the law a provision of this kind—which nearly resembles the provision now contained in the 27th rule of the Court of Common Pleas, (see Howe’s Practice, Page 572)—that “the right of an Attorney to appear for any party, shall not be questioned by the opposite party, unless the exception be taken at the first term,” (or, I would add, at the second term, when the opposite party lives without the Commonwealth,) “and when the authority of an attorney to appear for any party shall be demanded,” such attorney shall be sworn or affirmed to speak the truth, and if he “declare that he has been duly authorized to appear, by application made directly to him by such party, or by some person whom he believes has been authorized to employ him, it shall be deemed and taken to be evidence of an authority to appear and prosecute or defend, in any action or petition”—reserving however to the opposite party, on his or his counsel’s making oath or affirmation that he has, in his judgment, reasonable grounds for supposing that such Attorney has not been duly authorized, the right to continue his action, and at the term to which it is continued, to contest, by evidence, the right of such Attorney to appear in the action—provided he give to the attorney reasonable notice that his right to appear will be contested—the party making the objection, being held liable for the costs that may arise in consequence of his objection, if he fail to sustain it.

The principle argument,—and it is of itself, as I think, a sufficient and invincible one—on which I would insist in support of such a law as I have suggested, is that of strict right. If the admission be to any one a privilege, all, who desire that privilege, have as good a right to it as any one can have. None of us are entitled to exclusive privileges; and therefore, if this privilege be granted to one, the obligations of equity are imperative that it be also granted to each and every other one, who may desire it. Even the ability, learning, or other peculiar qualifications of an individual for the practice of the law, cannot with justice, be made a matter of inquiry by the Courts or the Legislature, as a condition of his being permitted this privilege—because those are matters, with which neither the Courts nor the public have any concern—they concern solely the lawyer himself and his clients. Any man, who is allowed to have the management of his own affairs, has the right to decide for himself whom he will employ as counsel—and if he choose to employ one, whom the public at large would not think the best or ablest that could he found, it is the right of the person so employed to have the same facilities afforded to him for discharging his service as counsel, that are afforded to others, whom the public may think much better or abler lawyers.

It may be proper however that a decent moral character be made a requisite for admission, and for this reason solely, as far as I can see, that otherwise individuals might sometimes put themselves there, from whom the Court would be in danger of insult.

Another ground, on which I would advocate a change in the law, is, that the present rules operate as a protective system in favor of the rich, or those who have at least a competency, against the competition of the poor. Some people have thought that a protective system in favor of the poor, against the competition of the rich, was a wise policy—but no one has yet ever dared advocate, in direct terms, so monstrous a principle as that the rich ought to be protected by law from the competition of the poor. And if such a principle is to be sustained by the laws of this Commonwealth, it would justify an open rebellion to put down the Government.

My own doctrine also is, and I have no doubt it is also that of the most of your number, that the professional man, who, from want of intellect or capacity for his profession, is unable to sustain himself against the free competition of his neighbors without the aid of a protective system, has mistaken his calling—and the public ought not, looking solely to their own interest and rights, to tolerate laws, that shall place them under any necessity whatever of employing such incompetent men, when abler once can be procured.—They (the public) ought, on the contrary, to have the most full and unqualified liberty of employing in their service, without let, hinderance, or any invidious distinction or disadvantage whatever, the best talent they can command. The present laws and rules, considering them as the acts of the community, are in fact specimens of the most wretched and self-cheating policy—for while they probably have the effect to invite into the profession few or no able men, who would not otherwise enter it, they exclude many able ones, who, but for them, would enter it. The community therefore take the trouble to make laws, whose natural and necessary operation is to produce a scarcity, where there would otherwise be an abundance of the very services, which they want—they actually go out of their way to do themselves an injury.

Another consideration entitled to weight in favor of the change, is, that if the profession were made accessible by the poor, the practice of the Bar would be likely to be more uniformly humane (I mean no imputation upon the profession at large) than it now is. Who are the Attorneys, whose rapacity has heretofore filled our jails with honest debtors? Who are they, that have ever been ready to extort, in the shape of bills of costs, poverty’s last shilling, and to feed and clothe, if not to pamper and bedeck, their own families, with food and dresses snatched and stripped from the mouths and bodies of the poor man’s children? I think they will rarely, if ever, be found to have been those, who had been reared in poverty themselves; who had known by experience the difficulties of that condition, and who had witnessed and participated in the disheartening embarrassments, occasioned to the poor man’s family, by the deduction of the lawyer’s bill from their scanty earnings. The poor, and those who have been poor, have too much fellow-feeling to get wealth, or even their subsistence, by grinding each other’s faces.

The present rules ought to be abolished for the further reason that a compliance with them, by those who can make good lawyers at all, is not necessary. I have heard, from men of great experience at the Bar, sentiments equivalent to this, that as an almost universal rule, it is not until after a person has entered the profession, and has a character to maintain, and business of his own to attend to, that he studies the law with any considerable intentness or effect. Now it this be so, much of the time, that is now spent in preparation, is little better than wasted.

But further—in a considerable portion of the cases, the compliance with the rules, when it is observed, is more nominal than real. The time, designed by the rules to be devoted, to study, instead of being thus devoted, is, probably by a majority of students, given much more to amusements than to books. Indeed a really industrious law student would generally be considered, by other students, a great curiosity. But even if all did study diligently and zealously, that fact would be no evidence that they were suitable persons to be admitted, in preference to others; because, to excel in the profession of the law, abilities are required, as peculiar almost, as those that are necessary to enable one to excel in painting, music or mechanics; and if a man have not these peculiar abilities, they cannot be acquired by three years study, if indeed they can be by the studies of a whole life. On the other hand, if a man have them, he will succeed, even though he should commence practice before he has studied half the time that our laws require—as is proved by the cases of some of the most eminent lawyers and advocates, that the country has ever produced. According to the criterion in Massachusetts, Henry Clay, Patrick Henry, William Pinkney and Chief Justice Marshall, when they commenced their career, must have been pronounced unqualified for a place, which the next moment would have been given perhaps to some stupid fop, whose only recommendation was, that he had spent three years, not in attending to his brains or his books, but in twirling his cane and brushing his whiskers. Indeed I think experience has proved that the direct tendency of our present rules, is to introduce into the profession more fops and fools than lawyers. The lawyers would enter it, without the rules—but the fops and fools would not find it profitable to do so. These facts illustrate the miserable policy of prohibiting one set of individuals from the pursuit of that art or profession, for which nature and inclination fit them, and of attempting to supply their place by offering to others, who have naturally neither the capacity nor inclination to fill it, exclusive privileges, as an inducement to make the trial. These restrictive and protective rules effect the double evil of shutting out some individuals from their natural and appropriate sphere, where they would be useful to themselves and the community, and of enticing others into what is to them an unnatural one, where they can do little for themselves, and little or nothing for the public. It would hardly be possible to devise rules, that should more uniformly prevent nothing but good, and accomplish nothing but evil, than these which are authorized and upheld by the Legislature.

I will now answer some of the objections, which I suppose will be made, to the passage of such a law as I have proposed.

One is, that there would he too many lawyers.—I might, in answer to this objection, ask how can there be too many lawyers, when the number of practising ones must, of necessity, be limited by the business and conventence of those, who have occasion to employ them?

But I think there is another answer—and that is, that, although there might be more than there are now, (which is very doubtful,) who would become nominally attorneys, and would occasionally fill writs in cases of necessity, there would yet not be so many, who would devote themselves steadily to the profession as their regular business. The reason why there would not be so many of this class, is, that there would be more men of talents in the profession, and they would of course receive all, or nearly all, the patronage. It would be of no use for an incapable man to attempt to establish himself as an attorney at all—because the people would give him no business—and no more able ones would enter the profession than could get a good living from the business, which the community would afford, because it is not characteristic of capable men to engage in any business, from which they cannot derive a good support. Whereas we know multitudes of weak men now enter the profession, and make it their regular business, although they derive only such a pittance from it as no spirited and able man would be content with.

Another objection, which I have heard made, is that if every man were allowed to commence actions, it would give rise to barratry. But how would it give rise to barratry? None, but men of decent and good moral characters, could commence actions—and is not the good moral character of one man as good a security that he will not commit barratry, as is the good moral charracter of any other man? Does loitering about a lawyer’s office three or four years, raise a man’s moral character so high above that of ordinary men, as to afford the community any security for his good behaviour, which they have not in the case of other men? Besides, barratry is a crime—an indictable offence—punishable by fine and imprisonment—and is it necessary, in addition to this, to go so far as to deprive certain men “of decent and good moral character,” of privileges, which—on certain conditions, that have in them no tendency whatever to prevent barratry—are granted to others to an indefinite extent, and have been granted to them until the country is overrun with lawyers so poor that, if poverty could induce men to commit barratry, we should have had enough of it long ere this?

But further—all that is necessary to enable a man now to commit barratry, and to have the profits of managing the suits, is for him just to take a power of attorney—yet we have no barratry, unless it be in the ranks of the profession.

And I think it may here be a very pertinent inquiry—whether the present rules do not favor, rather than obstruct, the commission and concealment of barratry by the members of the Bar? The members of the Bar have become an organized, associated body—the society, in the mass, exercising a discipline over the members, and professing to the public that they tolerate among their number none unworthy of the public confidence. The members of the association have thus taken to themselves, in some degree, a common character. In the preservation of this common character from suspicion, all are interested. And I think all will admit that the experience of the world has been, that such associnations, in guarding their associated character, uniformly pursue the policy of not being the first to expose the faults or crimes of their associates to the world, and generally of hushing suspicion if possible. It is natural that they should, for they have a strong personal interest to do so. But after public suspicion has once become so strong against an individual member that the character of the whole body is in danger—or when a case of criminality has become too notorious to be concealed, then the association become suddenly virtuous—affect a great deal of astonishment—probe the matter terribly—and if they find it necessary, expel the offender, and would then make the public believe that they have purified the association as with fire. Now is not all this farce? a mere humbugging of the community?

What then is the remedy? It is this. If the profession were thrown open to all, this combination of lawyers would doubtless be broken up—they, like other men, would hold themselves severally responsible for their own characters alone—they would have no inducement to wink at orattempt to hide the mal-practices of others—individuals, who should suppose themselves injured by the practice of an attorney, instead of laying his complaints before the Bar, would lay them before the grand jury, or some other tribunal—and it is no uncharitableness, it is only supposing lawyers to be like other men, to say, that it is probable the community would sometimes fare the better for it.

Another objection, which I suppose may be made by some, is that if the profession were thrown open to all, young men would be likely to enter it before they should be so qualified that they could he safely entrusted with the transaction of business—and that therefore those who should employ them, would be imposed upon.—And I suppose the present rules were established on the ground, that some rules, coming from the Court, were necessary in order to prevent men from being imposed upon by those, whom they might otherwise see fit to employ to do their business. Now it was really very kind, no doubt, on the part of the Court, thus to take the people’s business out of their hands, and assume so fatherly a control of it themselves, in order to avert from the people the natural consequences of their incapacity to judge of these things for themselves; yet, however benevolent their intentions undoubtedly were, I seriously suspect that their rules actually cause twice as much imposition as they provent; because, one, admitted under them, is ostensibly admitted on the ground of his being qualified for practice—whereas, in reality, his qualifications have nothing to do with his admission. After the candidate has been nominally a student the requisite time, he is admitted without inquiry, as a matter of course. Yet the forms of admission are such that his admission amounts to an indorsment and certificate, by the Bar, of his capacity and fitness to be entrusted with business. The Bar, in fact, actually recommend him to the confidence of the public, wherever he may go. Many, who are ignorant of the deceptive and fallacious character of this proceeding, repose confidence in the man on account of this indorsement and recommend then, and, in consequence, they too often find themselves to have been imposed upon with a vengeance. In short, this whole affair of rules, recommendations, admissions &c., although observed professedly to prevent imposition, is yet, in practice, little less than an organized system of imposition.

Let us now look on the other hand. If men were admitted, without regard to their qualifications, their admission would be no recommendation to the confidence of the public, and the client would ascertain for himself what a lawyer was made of, before he would entrust him with business at all. Every lawyer would then of necessity stand on his own merits and resources—he would have no recommendation from his brethren of the Bar to prop him up, or to shield him from his just responsibility for his errors. Young men, under these circumstance, would commence and proceed in their practice with much greater caution then they now do, and far this plain reason, that it would be necessary, both for their reputation and their interests, that they should do so.

But supposing that incompetent men should attempt to get professional business, and should succeed, and that those, who employed them, should suffer in consequence—on what principle must the Legislature proceed in sustaining laws to prevent such occurrences? Why, they must proceed on this principle—that the people are not to be allowed the management of their own affairs—that they are not to he trusted with the selection of agents to do their own business—but that if they want the services of a lawyer, for instance, the Legislature and the Courts will so far look after their interests as just to prescribe to them whom they must employ, if they wish to have their lawyer enjoy the ordinary facilities for doing their business. A fine doctrine this to preach to the people of Massachusetts.

I have another objection to a law or rule of Court, that shall make it necessary that the qualifications of a candidate, other than his moral character, be in any way whatever inquired into, as a preliminary to admission. It is that if the inquiry be made at all, it must be made by a board of lawyers, who are interested to keep him out, and who also, in some cases, may have special objects to accomplish by frustrating the success of particular individuals—in which contingencies they would be very likely to abuse their power to effect their purpose. Suppose, for example, that an individual, before applying for admission, should have avowed a determination, that, if admitted, he would not enter the combination of the members of the Bar, to keep up the prices, and throw obstacles in the way of competitors, in the profession—can there be a doubt that such an individual, on an examination as to his attainments, would be in much more than ordinary danger of being found to be not qualified for admission? I therefore object to having my rights, or my interests, or my feelings, or any other man’s rights, interests or feelings thus unnecessarily placed in the keeping of interested men, who have no claim to the guardianship of them.

If a young man should find that, in order to obtain the confidence and patronage of the community, he needs a certificate from the members of the Bar, of his qualifications, he would perhaps think it worth his while to go to some of them, and ask of them, as a favor, to examine and recommend him; but if he should be able to get [15b] along as well without their assistance, he has a perfect right, and, in some cases perhaps, would much prefer to do so. He ought therefore to be left at perfect liberty on this point, without having any other of his privileges affected by the course he may choose.

Another objection, which may be made to the law I propose, is, that the Courts might be incommoded and delayed by the arguments of ignorant men. I have already indirectly, given one answer to this objection, in showing (if I have shown it) that the active part of the profession would probably be more, rather than less, intellectual than it now is. Another answer is, that the people will of course, then as now, (because it will be for their interest to do so) employ the ablest lawyers that can be obtained—and if those, who spend four years in college, three years in an office, and £2500 in money, in fitting themselves for the Bar, are more intellectual than those can be, who may spend less time and money, or spend them in a different way, for that purpose, the presumption is that the people will find it out without the aid of the Legislature, and that, in consequence of it, the former class of practitioners will still have all, or nearly all the business, and young men, who are fitting themselves for the Bar, will still find it for their interest to pursue the same course of education as that now required—and the result will be that the Courts will have the pleasure of listening only to the same kind of arguments as those now addressed to them. But a better, and more conclusive answer to the objection, is that the Courts were made for and by the people, and not the people for or by the Courts. Suitors, when in Court, are the people, and it is their right to present their causes to their own Courts, by whatever counsel they may think it for their interest to present them, (provided it he done with civility,) and the Court must hear them without murmuring, or resign their seats.

I ought here to say, that I do not suppose that these arguments, to which I have alluded, will be put forward in purely good faith. They are too shallow to be honestly relied on by men capable of just and liberal views of the subject. They will be used, if used at all, by those, who dare not avow their real objections to the change. The true source of the opposition, if any should be made, will be, that there are those, who, either for themselves, or for some dear Son Johnny or Josey, want the aid of a protective system to give them a living, or make them respectable.

Having thus attempted to answer the objections, that occurred to me as the most likely to be brought against the law, which I have suggested, I wish now to state some further objections of my own to other portions of the existing laws. I object to the oath, that is required of attorneys, in all its particulars. (See St. 1785 Ch. 23)

In the first place, I object to the oath to bear true allegiance to the Commonwealth, and to support the Constitution. The right of rebelling against what I may think a bad government, is as much my right as it is of the other citizens of the Commonwealth, and there is no reason why lawyers should be singled out and deprived of this right. My being a friend or an avowed enemy of the constitution has nothing to do with the argument of a cause for a client, or with any other of my professional labors, and therefore it is nothing but tyranny to require of me an oath to support the constitution, as a condition of my being allowed the ordinary privileges for getting my living in the way I choose. It will be soon enough, after I shall have been convicted of treason, to refuse me the common privileges, or take from me the common rights of a citizen. It is the right of the citizen to decry and expose the character of the constitution, and if possible to bring it into contempt and abhorrence in the minds of the people, without forfeiting any of the ordinary privileges of citizens—and the recognition of this right constitutes one of the greatest safeguards of the public liberty. And if any one class of men, the moment they attempt to prove that our constitution is not a good one, and ought to be abolished, are to be denied any of the ordinary rights and privileges of citizens, then has that class been singled out for the especial tyranny of the government. There would be just as much propriety in requiring a farmer to take an oath to support the constitution, as a condition of his being allowed the privilege of entering his deed of record in a public recording office, as there is in requiring it of me, as a condition of my being allowed the privileges of an attorney. There would also be the same propriety in requiring this oath of the members of a manufacturing corporation, as a condition procedent to their receiving an act of incorporation, as there is in requiring it of me.

I object, in the next place, to the oath, which the attorney is required to take, that “if he know of an intention to commit any falsehood in Court, he will give knowledge thereof to the Justices of the Court, or some of them, that it may be provented.” I do not choose to be made an informer in this manner, against men with whose matters I have nothing to do. That is not what a lawyer goes into Court for—he goes there to defend the rights and interests of his clients, and for nothing else—and he has a right so to do, and to have all the ordinary facilities for doing it afforded to him, without this odious service being exacted of him. There would be just as much reason in requiring of the members of a manufacturing corporation, as the price of their charter, an oath that they will act as informers against all their neighbors, whom they may suppose to be dishonest in their dealings, and that “if they know of an intention,” on the part of one man, to cheat another in the price of a horse or a cow, “they will give notice thereof that it may be prevented.” I object to being made in any way an officer or servant of the Court, as a condition of my being allowed the ordinary privileges in doing the business of my clients. Any other service, such as taking charge of a Jury, ringing the bell or sweeping the court-room, (which, by the way, would be services a thousand times more honorable) might be required of me on the same ground as is this of an informer.

I object, in the last place, to the oath of the attorney, that he “will do no falsehood, nor consent to the doing of any in Court, that he will not wittingly or willingly promote or sue any false, groundless or unlawful suit, nor give aid or consent to the same; that he will delay no man for lucre or malice; but will conduct, in the office of an attorney within the Courts, according to the best of his knowledge and discretion, and with all good fidelity, as well to the Courts as to his clients.” I object to the whole of this oath for several reasons. First, it singles out lawyers as men worthy of especial suspicion—as men of doubtful honesty. If a lawyer is guilty of mal-practice, he is amenable to the laws; or if he is unfaithful to his clients, he is answerable in damages, in spite of his oath—and, if he is not guilty of mal-practice or unfaithfulness, he ought not to have the invidious suspicion, implied by this oath, fastened upon him. Without this oath, the community have the same security for the honesty of lawyers, that they have for the honesty of other men, and what more have they a right to demand? Clients also have the same security for the fidelity of their attorneys, that other men have for the fidelity of their agents, and what more have the laws a right to require that they shall have? If any individual client want the oath of his lawyer, is a security for his fidelity, let him make to him the insulting proposal, and persuade or purchase a compliance with it, if he can. But if he is satisfied to trust him without the oath, it is base business for the Legislature to interfere and say that the man ought not to be trusted except he be sworn.

Why should not physicians, before they are permitted to practice, he required to take an oath that they will always practice in good faith, and knowingly injure none of their patients? Why are not the members of manufacturing corporations, before they are allowed a charter, required to take an oath that they will defraud no man in the quality of the goods, that they may manufacture under that charter? Why is not the farmer, before he is allowed the privilege of securing to himself his property in his farm, by entering his dead in the public recording office, required to swear that he will never defraud any man in the price or quality of the produce of that farm? There would be as much reason in it as there is in requiring of a lawyer an oath that “he will not wittingly or willingly promote or sue any false, groundless or unlawful suit.”

The truth is that legislatures and Courts have made lawyers a privileged class, and have thus given them facilities, of which they have availed themselves, for entering into combinations hostile, at least to the interests, if not to the rights, of the community—such as to keep up prices, and shut out competitors. The natural result of such combinations also is, that the mass of the members will do more or less to screen individuals from suspicion. The consequence is, that the people have imbibed an extreme jealousy towards them, and exact from them oaths, containing such divers significant specifications, that, were he not kept in countenance by others, a man would consider them too humiliating to be taken. Now if the profession were throw open to all, lawyers would be no longer a privileged class—they probably could no longer enter into combinations that would be of any avail to them, and the jealousy of the people towards them would be at an end.