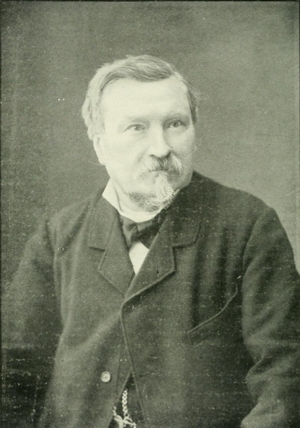

Gustave de Molinari, “On Socialism and Property Rights” (1849)

Note: This extract is part of The OLL Reader: An Anthology of the Best of the OLL, the table of contents of which can be found here. It is from "Part X: The Critique of Socialism and Interventionism".

For more information on socialism see:

- Socialism: A Study Guide and Reader

- Topic: Socialism and the Classical Liberal Critique

- People: School of Thought: Socialism

- Debate: Fabian Socialism vs. Radical Liberalism

|

Source

Gustave de Molinari, Les Soirées de la Rue Saint-Lazare: Entretiens sur les lois économiques et défense de la propriété (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849). </titles/1344#Molinari_0383_186>.

- Soirée 11. Draft Engish trans. </pages/gdm-soirees>.

Copyright

The copyright to this edition, in both print and electronic forms, is held by Liberty Fund, Inc.

The Text

Evenings on Saint Lazarus Street: The First Evening

4. Evenings 26 on Saint Lazarus Street 27 : The First Evening

[p. 5]

SUMMARY : Attitudes to the problem of society. – That society is governed by natural, immutable and absolute laws. – That property is the foundation of the natural organization of society. – Property defined. – Listing the attacks mounted today on the principle of property.[SPEAKERS: 28 A conservative.- A socialist.- An economist. 29 ]

THE CONSERVATIVE.Let us debate among ourselves, calmly, the formidable problems thrown up in these last few years. You [the Socialist], who wage a bitter war against present institutions, and you [the Economist], who defend them with certain reservations , what are you actually seeking?

THE SOCIALIST.We want to reconstruct society.

THE ECONOMIST.We want to reform it.

THE CONSERVATIVE.Oh you dreamers, my good friends, I would ask for nothing better [p. 6] myself, were it possible. But you are chasing chimeras.

THE SOCIALIST.What? To want the reign of force and fraud 30 to yield to that of justice; to wish that the poor were no longer exploited by the rich; to want everyone rewarded according to his labor – is all this to pursue a chimera, then?

THE CONSERVATIVE.This ideal, which all the Utopians 31 have put forward since the world began, unfortunately cannot be realized on this earth. It is not given to men to attain it.

THE SOCIALIST.I believe quite the opposite. We have lived till now in a corrupt and imperfect society. Why should we not be permitted to change it? As Louis Blanc said, 32 if society is badly constructed, can we not rebuild it? Are the laws on which this society rests, a society gangrenous to the very marrow of its bones, eternal and unchangeable? We have endured them thus far. Are we condemned to do so forever?

THE CONSERVATIVE.God has willed it thus.

THE ECONOMIST.Beware of taking God's name in vain. 33 Are you sure that the ills of society really stem from the laws on which society is based? [p. 7]

THE SOCIALIST.Where then do they come from?

THE ECONOMIST.Could it not be that these ills have their origin in the attacks made on the fundamental laws of society?

THE SOCIALIST.A likely story that such laws exist!

THE ECONOMIST.There are economic laws which govern society just as there are physical laws which govern the material world. Utility and Justice are the essence of these laws. This means that by observing them absolutely, we are sure to act usefully and fairly for ourselves and for others.

THE CONSERVATIVE.Are you not exaggerating a little? Are there really principles at work in the economic and moral sciences, ones absolutely applicable in all ages and places? I have never believed, I am bound to say, in absolute principles . 34

THE ECONOMIST.What principles do you believe in, then?

THE CONSERVATIVE.My goodness, I believe, along with all the other men who have looked closely at the things of this world, that the laws of justice and the rules of utility are essentially shifting and variable. I believe, accordingly, that we cannot base any universal and absolute system on these laws. M. Joseph de Maistre 35 was wont to say: everywhere I have seen men , but nowhere have I seen Man. 36 Well, I believe that one can say likewise, that there are societies, having particular laws, appropriate to [p. 8] their nature, but that there is no Society governed by general laws.

THE SOCIALIST.Perhaps so, but we want to establish this unitary and universal society.

THE CONSERVATIVE.I still believe with M. de Maistre that the laws spring from circumstances, and have nothing fixed about them…Do you not know that a law considered just in one society, is often regard as iniquitous in another? Theft was permitted in certain conditions in Sparta; polygamy is allowed in the Orient and castration tolerated too. Would you say, therefore, that the Spartans were shameless thieves and that Asians are despicable debaucherers? No! If you consider things rationally, you will conclude that the Spartans in permitting theft, were obeying particular exigencies of their situation, while Asians, in authorizing polygamy and tolerating castration, are subject to the influence of their climate. Read Montesquieu again! 37 This will persuade you that moral law does not take the same form in all places and at all times. You will agree with him that justice has nothing absolute about it. Truth this side of the Pyrenees, error the other side, said Pascal. Read Pascal again! 38

What is true of the just is no less true of the useful. You speak of the laws of utility as if they were universal and permanent. Your error is truly profound! Do you not know that economic laws have varied, and vary still, endlessly, as do moral laws?...Will your counter-argument be that nations fail to recognize their [p. 9] true interests when they adopt diverse and flexible economic legislation? You have against you, however, centuries of experience. Is it not proven, for example, that England owed her wealth to protectionism? Was it not Cromwell's famous Navigation Act 39 which was the starting point for her maritime and colonial greatness? She has recently abandoned this protectionism, however. 40Why? Because it has ceased to be useful to her, because it would spell her ruin after having made her rich. A century ago free trade would have been fatal to England; today it gives a new lease of life to English commerce. That is how much circumstances have changed!

In the domain of the Just and the Useful, all is mobility and diversity. To believe as you seem to do, in the existence of absolute principles , is to go astray lamentably, to misunderstand the very conditions for the existence of societies.

THE ECONOMIST.So you think that there are no absolute principles, either in morality or in political economy; you think everything is shifting, variable and diverse in the sphere of the Just and in the sphere of the Useful; you think that Justice and Utility depend on place, time and circumstance. Well, the Socialists have the same opinion as you. What do they say? They say that new laws are needed for new times. That the time has come to change the old moral and economic laws which govern human societies.

THE CONSERVATIVE.Criminal folly! [p. 10]

THE SOCIALIST.Why? Until now you have governed the world. Why should it not be our turn to govern it? Are you made of superior stuff to us? Or can you really affirm that no one is more fit than you to govern men? We put it to the vote of everyone. Ask the opinion of the wretched souls who languish at the bottom of society, ask whether they are satisfied with the fate which your lawmakers have left them. Ask them if they think they have obtained a fair share of the world's goods. As to your laws, if you had not framed them according to the selfish interests of your class, would your class be the only one to prosper? So, what would be criminal about our establishing laws which advantaged everybody equally?

You accuse us of attacking the eternal and unchanging principles on which society rests: religion, family and property. On your own admission, however, there are no eternal and unchanging principles.

Perhaps you might cite property, but in the eyes of your jurists, what is property in fact? It is a purely human institution which men have founded and decreed and which they are consequently in a position to abolish. Have they not, moreover, incessantly recast it? Does property today resemble ancient Egyptian or Roman property or even that of the Middle Ages? The appropriation and exploitation of man by man used to be accepted. You no longer accept this today, or anyway not in law. In most ancient societies the ownership of land was reserved to the State; you have rendered landed property accessible to everyone. [p. 11] You have, on the other hand, refused to give full recognition to certain kinds of property; you have denied the inventor the absolute title to his invention, and to the man of letters the absolute ownership of his writings. 41 You also came to understand that society had to be protected against the excesses of individual ownership of property and for the general good you passed the law of expropriation. 42

Well, what are we doing now? We are limiting property a bit more; we are subjecting it to more numerous restrictions, and to heavier burdens, in the public interest. So are we so guilty? Was it not you who marked out the direction we now follow?

As to the family, you admit that it has legitimately been able to assume in other eras and other countries, a different organization from that which prevails today with us. Why then, should we be forbidden to modify it again? Cannot man unmake everything he has made?

Then there is religion! Have not your lawmakers, however, always arranged it as they saw fit? Did they not begin by authorizing the Catholic religion to the exclusion of the others? Did they not finish by permitting all faiths and by funding some of them? 43 If they were able to regulate the manifestation of religious feeling, why should it be forbidden to us to regulate it in our turn?

Property, family, religion – you are soft wax which so many lawmakers have marked with their successive imprints – why should we not mark you also with ours? Why should we abstain from touching things which others have so often touched? Why should we respect relics [p. 12] whose guardians themselves have felt no scruple in profaning?

THE ECONOMIST.The lecture is deserved. You Conservatives, who admit no absolute, pre-existing and eternal principle in morality, any more than in political economy, no principle equally applicable to all eras and places, look where your doctrines lead! People throw them back at you. After having heard your moralists and your jurists deny the eternal laws of the just and the useful, only to put in their place this or that fleeting expedient, adventurous and committed minds, substituting their ideas for yours, wish to rule the world after you and differently from you. And if you conservatives are right, when you insist that no fixed and absolute rule governs the moral and material arrangement of human affairs, can one condemn these reorganizers of society? 44 The human mind is not infallible. Your lawmakers were perhaps wrong. Why should it not be given to other lawmakers to do better?

When Fourier, 45 drunk with pride, said: All the legislators before me were wrong, and their books are fit only to be burned, might he not, according to your own judgment, have been right? If the laws of the Just and the Useful come from men, and if it falls to men to modify them according to time, place and circumstance, was not Fourier justified in saying, with his eyes on history, that long martyrology of the nations, that the social legislation of the Ancients had been conceived within a false system and that the organization of a new social state was called for? In your insistence that no absolute and superhuman principle governs [p. 13] societies, have you not opened the floodgates to the Utopian torrent? Have you not authorized the first comer to refashion these societies you claim to have made? Does not socialism flow from your own doctrines?

THE CONSERVATIVE.What can we do about it? We are well aware, please believe me, of the chink in our armor. Therefore we have never denied socialism absolutely. What words do we use, for the most part, for socialists? We tell them: between you and us the difference is only a matter of time. You are wrong today, but perhaps in three hundred years, you will be right. Just wait!

THE SOCIALIST.And if we do not want to wait?

THE CONSERVATIVE.In that case, so much the worse for you! Since without prejudice to the future of your theories, we regard them as immoral and subversive for the present, we will hound them to our utmost ability. We will cut them down as the scythe cuts down tares 46 …We will dispatch you to our prisons and to penal servitude, there to attack the present institutions of religion, family and property. 47

THE SOCIALIST.So much the better. We rely on persecution to advance our doctrines. The finest platform one can give to an idea is the scaffold or the stake. Fine us, imprison us, deport us… we ask nothing better. If you could reestablish the Inquisition against socialists we would be assured of the triumph of our cause. [p. 14]

THE CONSERVATIVE.We are still in a position not to need this extreme remedy. The Majority and Power are on our side.

THE SOCIALIST.Until the Majority and Power turn in our direction.

THE CONSERVATIVE.Oh I am quite aware that the danger is immense; still we will resist until the end.

THE ECONOMIST.And you will lose the contest. You conservatives are powerless to conserve society.

THE CONSERVATIVE.That is a very categorical statement.

THE ECONOMIST.We will see if it is well-founded or not. If you do not believe in absolute principles, you must – is it not the case? – consider nations as artificial aggregations, successively constituted and perfected by the hand of man. These aggregations may have similar principles and interests, but they can also have opposing principles and interests. That which is just for one, may not be just for the other. What is useful for this one, may be harmful to that one. What is the necessary result, however, of this antagonism in principles and interests? War. If it be true that the world is not governed by universal and permanent laws, if it is true that each nation has principles and interests which are special to it, interests and principles essentially variable according to circumstances and the [p. 15] times, is war not in the nature of things?

THE CONSERVATIVE.Obviously we have never dreamed the dream of perpetual peace like the noble Abbé de Saint-Pierre. 48M. Joseph de Maistre has anyway shown beyond doubt that war is inevitable and necessary .

THE ECONOMIST.You admit then, and in effect you cannot not admit, that the world is eternally condemned to war?

THE CONSERVATIVE.War occurred in the past, we have it in the present, so why should it cease to be in the future?

THE ECONOMIST.Yes, but in the past in all societies the vast majority of the population were slaves or serfs. 49 Well, slaves and serfs did not read newspapers or frequent political clubs 50 and knew nothing of socialism. Take the serfs of Russia! Are they not such stuff as despotism can mould at will? Does it not make of them, just as it pleases, mere drudges or cannon-fodder?

THE CONSERVATIVE.Yet it is clear that there was good in serfdom.

THE ECONOMIST.Unfortunately, there is no longer any way of reestablishing it among us. There are no longer slaves nor serfs. There are the needy masses to whom you cannot deny the free communication of ideas, to whom indeed you are constantly requested all the time to make [p. 16] the realm of general knowledge more accessible. Would you prevent these masses, who are today sovereign, from drinking from the poisoned well of socialist writings? Would you prevent their listening to the dreamers who tell them that a society where the masses work hard and earn little, while above them lives a class of men who earn a lot while working very little, is a flawed society and one in need of change? No! You can proscribe socialist theories as much as you like, but you will not stop their being produced and propagating themselves. The press will defy your prohibitions.

THE CONSERVATIVE.Ah, the press, that monumental poisoner. 51

THE ECONOMIST.You can muzzle it and proscribe it for all you are worth. You will never be done with slaying it. It is a Hydra whose millions of heads would defeat even the strength of Hercules.

THE CONSERVATIVE.If we had a decent absolute monarchy…

THE ECONOMIST.The press would kill an absolute monarchy just as it killed the constitutional monarchy, and failing the press, books, pamphlets and conversation would do the trick.

Today, to speak only of the press, that powerful catapult is no longer directed solely against the government, but against society too.

THE SOCIALIST.Yes, for some years the press has been on the march, thank God!

THE ECONOMIST.Once it stirred up revolutions in order to change [p. 17] the type of government; it stirs them up today to change society itself. Why should it not succeed with this plan as it did with the other? If nations were fully guaranteed against foreign conflicts, perhaps we could succeed in bringing to heel for good the violent and anarchic factions which operate domestically. You yourself agree, however, that foreign war is inevitable, since principles and interests are changeable and diverse and no one can claim in response that war, harmful today to certain countries, will not be useful to them tomorrow. Well, if you have no faith in anything save sheer Force to put socialism down, how are you going to succeed in containing it, when you are obliged to concentrate that Force, your final resort, on the foreign enemy? If war is inevitable, is not the coming of revolutionary socialism inevitable too?

THE CONSERVATIVE.That, alas, is what I am truly afraid of. This is why I have always thought of society as marching briskly towards its ruin. We are the Byzantine Greeks and the barbarians are at the gates.

THE ECONOMIST.Is that the position you have reached? You despair of the fate of civilization and you watch the rise of barbarism, waiting for that final moment when it comes pouring over your battlements. You really are so many Byzantine Greeks... Well if that is how it is, let the barbarians in. Better still, go out to meet them and hand the keys to the sacred city over to them, humbly. Perhaps you will succeed in assuaging their fury. [p. 18] Beware, however, of redoubling and pointlessly prolonging your resistance. Does not history record that Constantinople was sacked and that the Bosphorus was full of blood and corpses for four days? 52 You Greeks of the new Byzantium, be fearful of the fate of your ancestors and please spare us the agony of a hopeless resistance and the horrors of being taken by storm. If Byzantium cannot be saved, make speed to hand it over.

THE SOCIALIST.So are you acknowledging that the future belongs to us?

THE ECONOMIST.God forbid! I do think, however, that your enemies are wrong to resist you if they have despaired of defeating you, and I imagine that in not attaching themselves to any fixed and immutable principle, they have ceased to expect to be victorious. Conservatives are powerless to conserve society, that is all I wanted to demonstrate. Now, however, I will tell you other organizers, that you too would be powerless to organize it. You could take Byzantium and sack it; but you would not be able to govern it.

THE SOCIALIST.What do you know about it? Have we not ten organizations for your one? 53

THE ECONOMIST.You have just put your finger on it. Which socialist sect do you belong to? Please tell me. Are you a Saint-Simonian? 54

THE SOCIALIST.No? Saint-Simonianism is old hat. To begin with, it was an aspiration rather than a program… And the disciples have ruined the aspiration without finding the program. [p. 19]

THE ECONOMIST.Are you a Phalansterian? 55

THE SOCIALIST.It's an attractive idea but the morality of Fourierism is quite risqué. 56

THE ECONOMIST.Are you a Cabetist?

THE SOCIALIST.Cabet is a brilliant mind but uncultured. 57 He understands nothing, for example, about art. Imagine if you will, the people in Icaria painting statues. The faces of Curtius - that is the ideal of Icarian art. What a barbarian! 58

THE ECONOMIST.Are you a follower of Proudhon? 59

THE SOCIALIST.Proudhon, is he not a fine destroyer for you? How well he demolishes things! Up to now however all he has managed to set up is his exchange bank and that is not enough. 60

THE ECONOMIST.So, not Saint-Simon, not Fouriér, nor Cabét, nor Proudhon. So what are you then?

THE SOCIALIST.I am a socialist.

THE ECONOMIST.Tell us more though. To what type of socialism do you subscribe? 61

THE SOCIALIST.To my own. I am convinced that the great problem of the organization of labour has not yet been resolved. We have cleared the ground, we have laid the foundations, but we have not built the structure. Why should I not seek like [p. 20] anyone else to build it? Am I not driven by the pure love of humanity? Have I not studied science and meditated for a long time on the problem? And I think I can say that…well not yet actually…there are certain points which are not completely clear ( pointing to his forehead) but the idea is there…and you will see it later on.

THE ECONOMIST.This is to say that you too are looking for your version of the organization of labor. You are an independent socialist. You have your own particular bible. In fact, why not? Why should you not receive like anyone else the spirit of the Lord? Then again, why should it not come to others as much as to you? So we have lots of different approaches to the organization of labor.

THE SOCIALIST.So much the better. The people will be able to choose.

THE ECONOMIST.Right by a majority vote. But what will the minority do?

THE SOCIALIST.It will give in to the majority.

THE ECONOMIST.And if it resists? I admit of course that it will submit willingly or by force. I admit that the organization favored by the majority of voters will be installed. What will happen if someone – you, me or someone else- discovers a superior arrangement?

THE SOCIALIST.That is not likely.

THE ECONOMIST.On the contrary, it is very likely. Do you not believe in the dogma of indefinite perfectibility? [p. 21]

THE SOCIALIST.Most certainly. I believe that humanity will cease to progress only if it ceases to exist.

THE ECONOMIST.Well, whence comes the progress of humanity in the main? If one is to believe your learned men, it is society which makes man. When social organization is bad, man either stagnates or retrogresses. When it is good, man grows and progresses…

THE SOCIALIST.What could be more true?

THE ECONOMIST.Could there be anything more desirable in the world, then, than securing the progress of our organization of society? If this is to happen, what will the constant preoccupation of the friends of humanity have to be? Will it not be to invent and plan more and more perfect organizations?

THE SOCIALIST.Yes, probably. What do you see as wrong about that?

THE ECONOMIST.In my view this means permanent anarchy. A way of organizing society has just been set up and it functions, more or less well or badly, because it is not perfect…

THE SOCIALIST.Why not?

THE ECONOMIST.Does not the doctrine of indefinite perfectibility exclude perfection? What is more I have just cited you half a dozen versions of socialism and you were not satisfied with any of them. [p. 22]

THE SOCIALIST.That proves nothing against the ones which will appear later. And so I have the strong conviction that the one I favor…

THE ECONOMIST.Fourier worked out his perfect arrangements and yet you do not want them. Likewise you will run up against people who do not like yours. Some sort of system is in operation, whether good or bad. Most people like it, but a minority do not. From this springs conflict and struggle. Take note, moreover, that future arrangements possess an enormous advantage over present ones. People have not yet noticed their shortcomings. In all probability the new system will carry the day… until such time as it too is replaced by a third system. But do you really believe that a society can change its arrangements on a daily basis, without danger? Look what an appalling crisis a simple change of government has entailed for us. 62 What would it be like with a with a change in the whole of society?

THE CONSERVATIVE.The mere thought of it makes me shiver. What a frightful mess! Well, is that not the spirit of innovation for you?

THE ECONOMIST.Try as you might, you will not stop it. The spirit of innovation is a fact...

THE CONSERVATIVE.To the world's misfortune.

THE ECONOMIST.Not so. Without the spirit of innovation, men would still be eating acorns or [p. 23] nibbling grass. Without the spirit of innovation, you would be an uncouth savage, dwelling under the trees, rather than a worthy man of property with a dwelling place in town and another in the country, well fed, well-clad and well-housed.

THE CONSERVATIVE.Why has not the spirit of innovation stayed within its proper limits?

THE SOCIALIST.Selfish fellow!

THE ECONOMIST.The spirit of innovation in man has no limits and will perish only when man himself perishes. It will modify perpetually everything men have set up, and if, as you assert, the laws which regulate human societies are of human origin, the spirit of innovation will not be checked in the face of these laws. It will modify them, change them and overthrow them for as long as the human sojourn on earth continues. The world is given to incessant revolutions, to endless strife, unless…

THE CONSERVATIVE.Unless…

THE ECONOMIST.Unless, in fact, there are absolute principles , unless the laws which govern the moral and economic world, are pre-established laws like those which govern the physical world. If it were thus, if societies had been set up by the hand of Providence, would one not have to take pity on the pygmy, swollen with pride, who tried to substitute his work for that of the Creator? Would it not be just as puerile [p. 24] to want to change the foundations on which society rests as to change the orbit of the earth? 63

THE SOCIALIST.Without any doubt. Do they exist, though, these providential laws, and even supposing they do, are Justice and Utility among their key features?

THE CONSERVATIVE.That is grossly impious. If God has organized the various societies Himself, if He made the laws which regulate them, it is obvious that these laws are in their essence just and useful and that the sufferings of mankind flow from our not observing them.

THE ECONOMIST.Well said, but are you not in your turn obliged to admit that these laws are irreversible and unchangeable?

THE SOCIALIST.Well, why do you not reply then? Are you unaware, therefore, that nature proceeds only by universal and unchangeable laws? I also ask whether nature could proceed otherwise. If natural laws were partial, would they not come into conflict with each other constantly? If they were variable, would they not leave the world exposed to endless disruption? I can no more conceive that a natural law might not be universal and unchanging than you can conceive that a law emanating from God might not have Justice and Utility at its core. The only thing is, I doubt whether God was involved in the organization of human societies. Do you know why I am skeptical about this? Because your societies have detestable arrangements, because the history of humanity until now has been no more [p. 25] than a deplorable, hideous tale of crime and poverty. To attribute to God Himself the arrangements of these societies, vile and poverty-stricken as they are – would this not be to hold Him responsible for evil? Would this not be to justify the reproaches of those who accuse Him of injustice and cruelty?

THE ECONOMIST.May I be permitted to suggest that from the fact that these providential laws exist, it does not necessarily follow that mankind must prosper? Men are not mere bodies, lacking life and will, like the spheres one sees moving in an eternal order under the governance of physical laws. Men are active and free beings; they can obey or not obey the laws that God has given them. The only thing is, when they do not follow them they are rendered criminal and wretched. 64

THE SOCIALIST.If it were indeed thus, they would always obey them.

THE ECONOMIST.Yes, if they were familiar with them, and being thus familiar, knew that non-compliance with these laws must inevitably do them harm. That, however, is precisely what they do not know.

THE SOCIALIST.So are you asserting that all the ills of humanity have their origin in the non-observation of the moral and economic laws which govern society?

THE ECONOMIST.I am saying that if humanity had always obeyed these laws, the sum total of our ills would likewise always have been the smallest conceivable. Does that answer you sufficiently? [p. 26]

THE SOCIALIST.Absolutely. I would very much like to know, however, precisely what these miraculous laws are.

THE ECONOMIST.The fundamental law on which rests all social organization, and from which flow all the other laws, is PROPERTY. 65

THE SOCIALIST.Property? Come off it! Surely it is precisely property from which flow all the evils of humankind.

THE ECONOMIST.I assert the contrary. I assert that the wretchedness and the iniquities from which men have never ceased to suffer, do not come from property. I maintain that they come from transgressions, by individuals or society itself, temporary or permanent ones, legal or illegal, committed against the principle of property. I am saying that had property been faithfully respected from the beginning of the world, humanity would continually have enjoyed, in every era, the maximum welfare consistent with the degree of advancement of the arts and sciences, along with complete justice.

THE SOCIALIST.What a lot of assertions! And it would seem that you are in a position to substantiate your claims.

THE ECONOMIST.I would think so.

THE SOCIALIST.All right, so substantiate them then!

THE ECONOMIST.I ask nothing better. [p. 27]

THE SOCIALIST.First of all, please be so good as to define "property".

THE ECONOMIST.I will do better than that; I will start by defining man himself, at least from the economic point of view.

Man is a combination of physical, moral and intellectual powers. These various powers need to be constantly exercised, constantly restored by the acquisition of other similar powers. When they are not so restored, they perish. This is as true of intellectual and moral powers as it is of physical ones.

Man is thus perpetually obliged to assimilate new powers. How is he made aware of this need? By pain and sorrow. Any loss of powers is painful. Any acquisition of powers, any achievement is accompanied, on the other hand, by enjoyment. Driven by this double spur, man takes care endlessly to exercise or augment the set of physical, intellectual and moral powers which constitute his being. This is the reason for his activity.

When this activity occurs, when man acts 66 with a view to repairing or increasing his powers, we say that he is working. If the elements from which man extracts the potential advantages he assimilates, were always within his reach, and nature had prepared them for his use, his work would be reduced to a negligible level. That, however, [p. 28] is not how things are. Nature has not done everything for man; she has left him much to do. She supplies him liberally with the raw material for all the things he needs to perfect himself, but she obliges him to give a host of diverse forms to this raw material in order to make it usable for him.

The preparation of things necessary to consumption is called production.

How is production effected? By the action of the powers or faculties of man on the elements with which nature supplies him.

Before he can consume, man is therefore obliged to produce. All production implying some expenditure of powers, also implies pain and effort. One undergoes this effort and suffers this pain with a view to gaining some enjoyment, or, and this comes to the same thing, sparing oneself some worse suffering. One gains this pleasure or avoids this suffering by means of consumption. To produce and consume, to endure and enjoy, that is human life in a nutshell.

THE CONSERVATIVE.Are you so bold as to say that in your view Pleasure ought to be the sole purpose man should aim at on this earth?

THE ECONOMIST.Do not forget that this involves moral and intellectual enjoyment as well as the physical kind. Do not forget that man is a physical, moral and intellectual being. The whole question is: will he develop in these three respects or will he degenerate? If he neglects his moral and intellectual needs entirely, in favor of his physical appetites, he will degenerate morally and [p. 29] intellectually. If he neglects his physical needs so as to increase his intellectual and moral ones, he will degenerate physically. In both eventualities he will suffer in the one direction, while enjoying himself to excess in the other. Wisdom consists in maintaining the balance between the faculties with which one has been endowed, or in producing such a balance when it does not exist. Political economy, however, does not have to concern itself, or not directly anyway, with this inner ordering of our human faculties. Political economy is concerned only with the general laws governing the production and consumption of wealth. The way in which each individual should deploy the restorative powers of his being, concerns morality .

To suffer as little as possible, physically, morally and intellectually, and to enjoy as much as possible, from this triple point of view – this is what constitutes, in the final analysis, the great motivating principle in human life, the pivot around which all our lives move. This motive or pivot is known as self-interest .

THE SOCIALIST.You regard self-interest as the sole motive of human action and you say that it consists in sparing oneself pain and obtaining gratification. But is there not any more noble motive to which one might appeal? Might one not find the more elevated stimulus of the love of humanity more exciting than the ignoble lure of personal pleasure? Instead of yielding to self-interest, might one not obey the imperative of devotion to others? [p. 30]

THE ECONOMIST.Devotion to others is no more than one of the constituent parts of self-interest.

THE CONSERVATIVE.What does that mean? Are you forgetting that devotion implies sacrifice and that sacrifice involves suffering?

THE ECONOMIST.Yes, sacrifice and suffering on one side, but satisfaction and enjoyment on another. When one sacrifices oneself for one's neighbor, one condemns oneself, usually at least, to some material privation, but one experiences in exchange, moral satisfaction. If the effort involved outweighed the satisfaction derived from it, one would not sacrifice oneself for someone else.

THE CONSERVATIVE.What about the martyrs?

THE ECONOMIST.The martyrs themselves could supply me with witnesses in support of my case. In them, the moral sentiments of religion outweighed the physical instinct of self-preservation. In exchange for their bodily suffering they experienced moral pleasure of a more intense kind. When one is not armed to a high degree with religious feeling, one does not expose oneself, at least not willingly, to martyrdom. Why is this? It is because the moral satisfaction derived is weak and one finds it too dearly purchased in terms of the physical suffering.

THE CONSERVATIVE.But if that is the way of it, the men in whom physical appetite predominates, will always sacrifice the satisfaction of their more lofty aspirations, to that of their [p. 31] lower ones. Their interest will always be to wallow in the gutter…

THE ECONOMIST.This would be so if human existence were limited to this earth. The individuals in whom physical appetites predominate would, in such a case, have no interest in repressing them. Man is not, however, or does not believe himself to be, a creature of a mere day. He has faith in a future life and strives to perfect himself, in order to ascend to a better world rather than descend to a worse one. If he foregoes certain pleasures in this life, it is in order to acquire superior ones in another life.

If he has no faith in these future satisfactions, or reckons them inferior to those present satisfactions which religion and morality command him to give up in order to obtain them, he will not agree to this sacrifice.

Whether the satisfaction is present or future, however, whether it is located in this world or another, it is always the end which man selects for himself, the constant and unchanging motive behind his actions.

THE SOCIALIST.When it is elaborated like this, one can, I think, accept self-interest as the sole motive of man's actions.

THE ECONOMIST.Driven by his own self-interest, as he sees it, man acts and works. It is the role of religion and morality to teach him how best to invest his effort…

Man therefore strives incessantly to reduce the sum of his sorrows and increase that of his joys. How can he achieve this double outcome? By [p. 32] obtaining, in exchange for less work, more things suitable for consumption, or, which comes to the same thing, by perfecting his labor.

How can man perfect his labor? How can he obtain a maximum of satisfaction in exchange for a minimum of effort?

He can do it by managing efficiently the powers he possesses, by carrying out the work which best suits his abilities and by accomplishing the task in the best possible way.

Now experience proves that this result can be secured only through the most perfect division of labor.

Men's best interests naturally lie therefore in the division of labor. The division of labor, however, implies a bringing-together of individuals, societies and exchanges.

If men remain isolated, if they satisfy all their needs individually, they will expend the maximum effort to obtain a minimum of satisfaction. 67

Even so, this interest which men have in uniting, with a view to reducing their labor and increasing their economic satisfaction, would perhaps not have been sufficient to bring them together, had they not been first of all drawn to each other by the natural stimulus of certain needs which cannot be met in isolation, plus the need to defend – what shall we call it? – their property.

THE CONSERVATIVE.What? Are you saying property exists in isolation? According to those learned in law, it is society which creates it. [p. 33]

THE ECONOMIST.If society creates it, then society can abolish it too, a consideration which would make the Socialists who demand its abolition less egregiously guilty. Society did not, however, create property, it being rather the case that property created society.

What is property? 68

Property derives from a natural instinct with which the whole human species is endowed. This instinct reveals to man, prior to any reflection, that he is master of his own person and may use as he chooses all the potential attributes constituting his person, whether they remain part of him, or he has in fact separated himself from them. 69

THE SOCIALIST.Separated? What does this mean?

THE ECONOMIST.Man has to produce if he wants to consume. In producing he expends, separates from himself, a certain part of his physical, moral and intellectual powers. Products contain the effort expended by those who made them. Man does not cease to own, however, these efforts he has alienated from himself under the pressure of necessity. Human understanding is not deceived and will condemn, without distinction, attacks made on internal and external property. 70

When man is denied the right to own the [p. 34] part of his powers which he separates from himself when he is working, when the right to dispose of it is allocated to others, what happens? That separation, that using up of his powers, implies some degree of pain, and the man thus ceases working unless someone forces him to.

To abolish the rights of man to the ownership of the fruits of his labor, is to prevent the creation of the products concerned.

To seize control of a part of these products is likewise to discourage their creation; it is to slow down man's activity by weakening the motive impelling him to act.

In the same way, to threaten internal property ; to oblige an active and free being to undertake work he would not personally undertake, or to bar him from [p. 35] certain branches of work, that is to deflect his faculties away from the use he would naturally select, is to diminish that man's productive power.

Any assault on property, internal or external, alienated or not, is contrary to Utility as well as to Justice.

How comes it, then, that assaults have been made against property, in every period of history?

Given that any work entails an expenditure of effort, and any expenditure of effort a degree of pain, some men have wished to spare themselves the latter, whilst claiming for themselves the satisfaction it procures. They have consequently made a speciality of stealing the fruits of other men's labor, either by [p. 36] depriving them of their external property, or reducing them to slavery. They have gone on to construct societies organized to protect them and the fruits of their pillaging against their slaves or against other predators. This lies at the origin of most societies.

This quite unwarranted usurpation by the strong of the property of the weak, however, has been successively repeated. From the very beginnings of society an endless struggle has obtained between the oppressors and the oppressed, the plunderers and the plundered; from the very beginning of societies, the human race has constantly sought the emancipation of property. History abounds with this struggle. On the one hand you see the oppressors defending the privileges [p. 37] they have allotted themselves on the basis of the property of others; on the other we see the oppressed, demanding the abolition of these iniquitous and odious privileges. 71

The struggle goes on and will not cease until property is fully emancipated.

THE CONSERVATIVE.But there are no more privileges!

THE SOCIALIST.But property has all too many privileges!

THE ECONOMIST.Property is scarcely freer today than it was before 1789. It may even be less free. Only, there is a difference: before 1789, the restrictions placed on property rights were advantageous to some people: today, for the most part, no one benefits, without these restrictions being any the less harmful, however, to all of us. 72

THE CONSERVATIVE.Where, though, do you see these pernicious restrictions?

THE ECONOMIST.I am going to enumerate the main ones…

THE SOCIALIST.One further observation. I readily accept property as supremely equitable and useful in the state of isolation. A man lives and works alone. It is entirely fair that this man should have sole enjoyment of the fruits of his labor. It is equally useful that he be assured of holding on to his property. Can this regime of individual property be maintained fairly and usefully, however, in the social state? [p. 38]

I am also happy to admit that Justice and Utility prescribe, in this common state as much as in the other, that the entire property of each individual and that portion of his powers that he has alienated from his person by working, be recognized as his. Would individuals really, however, be able to enjoy these two forms of property, if society were not organized in such a way as to guarantee them this satisfaction? If this indispensable organization did not exist; if by some mechanism or other, society did not distribute to each person the equivalent of his labor, would not the weak man find himself at the mercy of the strong, would not some people's property be perpetually intruded on by the property of others? And if we were so imprudent as to emancipate property fully, before society was fully empowered with this distributive mechanism, would we not be witness to increasing encroachments of the strong on the property of the weak? Would not the complete emancipation of property 73 aggravate the ill rather than correcting it? 74

THE ECONOMIST.If the objection were sound, if it were necessary to construct a mechanism for the distribution to each person of the equivalent of his labor, then clearly socialism would clearly have its raison d'être and I like you would be a socialist. In fact, this mechanism you wish to establish artificially, exists naturallyand it works. Society has been organized: the evil which you attribute to its lack of organization, derives from obstacles preventing the free play of that organization.

THE SOCIALIST.Are you so bold as to claim that, by allowing all men to manage their property as they see fit, in the social circumstances [p. .39] we live in, we would find things working out by themselves in such a way as to render each man's labor as productive as possible, and the distribution of the fruits of the labor of all, fully equitable? …

THE ECONOMIST.I am bold enough to claim this.

THE SOCIALIST.So you think it would become unnecessary, leaving aside production, to plan at least distribution and exchange, to free up circulation...

THE ECONOMIST.I am sure of it. Let property owners freely go about their business. Let property circulate and everything will work out for the best. 75

In fact, property owners have never been left to go freely about their business and property has never been allowed to circulate freely.

Judge for yourself.

Is it a matter of the property rights of the individual man; of the right he has to use his abilities freely, insofar as he causes no damage to the property of others? In the present society, the highest posts and the most lucrative professions are not open; one cannot practice freely as a solicitor, a priest, a judge, bailiff, money-changer, broker, doctor, lawyer or professor. Nor can one straightforwardly be a printer, a butcher, baker or entrepreneur in the funeral business. 76 We are not free to set up a commercial organization, a bank, an insurance company, 77 or a large transport company, nor free to build a road or establish a charity, nor to sell tobacco or gunpowder, or saltpeter, nor to carry [p. .40] mail, or print money, 78 nor to meet freely with other workers to establish the price of labor. 79 The property a man holds in himself, his internal property , is in every detail shackled.

Man's ownership of the fruits of his labor, his external property , is equally impeded. Literary and artistic property and the ownership of inventions are recognized and guaranteed only for a short period. Material property is generally recognized in perpetuity, but it is subject to a multitude of restrictions and charges. Gifts, inheritance and loans are restricted too. Trade is heavily encumbered as much by capital transfer taxes, registration charges and stamp duty, by licensing and by customs duties, as by the privileges granted to agents working as intermediaries in certain markets. Sometimes, in addition, trade is completely prohibited outside certain limits. Finally, the law of expropriation on grounds of public utility, endlessly threatens such weak remnants of Property as the other restrictions have spared.

THE CONSERVATIVE.All the restrictions you have just listed were established in the interests of society.

THE ECONOMIST.That may be true. Those who brought them in, however, brought about a pernicious result, for all these restrictions act, in different degrees, and some with considerable impact, as causes of injustice and harm to society.

THE CONSERVATIVE.So that by destroying them we would come to enjoy a veritable paradise on earth. [p. .41]

THE ECONOMIST.I do not say that. What I do say is that society would find itself in the best possible situation, in terms of the present state of development in the arts and science.

THE SOCIALIST.And you are setting out to prove it?

THE ECONOMIST.Yes.

THE CONSERVATIVE. AND THE SOCIALIST.Now there is a utopian for you! 80

Molinari's Long Footnote about External propertyOne of our most distinguished economists, M. L. Leclerc, 81 has recently put forward a theory on the origin of external property, very like the one above. The differences are in form rather than in substance. Instead of an alienation of internal powers, M. Leclerc sees in external property a consumption of life and bodily organs. I quote:

The phenomenon of the gradual consumption and of the extinction, not of the individual self, which is immortal, but of life; this unthinkable breakdown of the faculties and organs, when it takes place as a result of the useful effort called work, seems to me very worthy of attention; for although this outcome [this breakdown] is unavoidable, either to maintain the productive effort itself, or to supplement what may still be in working order or perhaps replace what can no longer work, it is quite clear that such an outcome is painfully achieved. Its real costs include the amount of time it took, and if we may put it thus, the call it made on the faculties and bodily organs irrevocably used up to obtain it. This part of my life and my strength is gone forever. I can never recover it. Here it is, invested as it were, in the result of my efforts. It alone represents what I used legitimately to possess and no longer have. I did not use only my natural right in practising this substitution. I followed my conservative instinct; I submitted myself to the most imperious of necessities. My property rights are there! Work is therefore the certain foundation, the pure source, the holy origin of the rights of property. Otherwise the self is not primordial and original property, and the faculties, an expansion of the self and the organs put to its service, do not belong to it, which would be intolerable.

"To make use of one's time", "to waste it", "to use it well or badly"; "to work oneself to death in order to live"; "to devote an hour or a day": these are familiar phrases used for centuries, integral parts of any human language, which itself is thought made manifest. The self is therefore perfectly aware of foolish or wise, useful or unproductive deployment of its powers, and as it also knows that these powers belong to it, it readily infers from this a potential and exclusive claim on the useful outcomes of this inevitable extinction, when it has been laboriously and fruitfully achieved. Public awareness upholds, directly and spontaneously, these serious principles, these strikingly obvious truths, apparently without engaging in the long disquisitions which we intellectuals regard as obligatory.

Yes, my life belongs to me, as does the right to make of it, freely, a generous sacrifice to humankind, to my country, to my fellow-man, to my friend, my wife, my child. My life is mine, I devote a part of it to what may serve to prolong it. What I have obtained is therefore mine and I can also devote it entirely to those who are dear to my affections. If the effort is successful, religion explains this in terms of divine favor; if it is skillful, the Economist can attribute it to the improved operation of my faculties; if by chance the output exceeds my needs, it is quite obvious that the surplus [p. 36] again belongs to me. I therefore have a right to use it to add other satisfactions to that of living. I have a right to keep it aside for the child whom I might father, or against that terrible time of powerlessness, old age. Whether or not I convert the surplus, or trade it, utility for utility, value for value, it is still mine, since, as cannot be emphasised too much, it remains always the clear representation of a part of my life, of my faculties and my bodily parts, expended in work, which produces this surplus. Have I not committed part of the time given to me to live on Earth, so as to possess, honorably and legitimately, something which, when I close my eyes for the last time, I bequeath to those I love – clothes, furniture, goods, a house, land, contracts, money, and so on. Am I not, in reality, leaving my life and my faculties to those whom I love? I might have spared myself some effort or rendered that effort less painful, or increased my personal consumption. How much sweeter it is, however, to me, to transfer to my loved ones what was mine by right! This is a warm and consoling thought, which bolsters up courage, charms the heart, inspires and safeguards virtue, inclines us to noble commitments, holds different generations together and results in an improvement of our human lot, by the gradual growth of wealth.

Leclerc. – "Some Simple Observations on the Rights of Property" – Journal des Économistes , issue of 15 October, 1848. 82

Endnotes for Soirée 1

26 "Soirées" might be translated as “evenings,” “conversations,” or “dialogues”. It suggests a meeting of people with different viewpoints who gather for conversation and discussion on various topics. The reviewer of the book in the JDÉ (a journal very sympathetic to Molinari’s free market views) was puzzled by the title and suggested that “entretiens” (or “discussions”) would have been a better description of the book’s contents. Towards the end of the book Molinari himself describes the “Soirées as "causeries” (discussions). [See the glossary entry on “Soirées.” ]

27 Saint Lazarus Street in Paris got its name from the religious order of Saint Lazarus which ran a leprosy hospital before the Revolution. It later became the site for one of the major railway stations in Paris. The home of the young liberal journalist Hippolyte Castille (1820-1886) was on the rue Saint-Lazare. It had been at one stage the official residence of Cardinal Fesch (1763-1839) but was now the meeting place for a small group of liberals which included Frédéric Bastiat, Gustave de Molinari, Joseph Garnier, Alcide Fonteyraud, and Charles Coquelin who met regularly between 1844 and early 1848 to discuss political and economic matters. It was thus Castille's home which supplied the name for Molinari's book, Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare (1849). See Gérard Minart, Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912), pour un gouvernement à bon marché dans un milieu libre (Paris: Institut Charles Coquelin, 2012), p. 80.[See the glossary entry on "Rue Saint-Lazare" and "Castille." ' Fonteyraud"]

28 Molinari uses the word "interlocuteurs" which might be translated as "interlocutors" (which has an archaic sense to it), "discussants" , "speakers" , or "debaters". We have chosen "speakers" .

29 Molinari was criticized by the reviewer of his book in the JDE for misrepresenting the views of the mainstream Economists by using the name "The Economist" to express views which were those of Molinari alone, especially his ideas on the private "production of security" in S11 and his opposition to the compulsory acquisition of property by the state in S3, although this may well have been the young and radical Molinari's provocative implication (he was 30 when the book was published). Yet, it can be seen here that Molinari lists the speakers as "a" conservative, "a" socialist, and "an" economist" and thus it might be argued that he did not necessarily mean "all" socialists or "all" economists.

30 Molinari uses the term "la ruse" here which was a key term used by Bastiat in his theory of "sophisms". Bastiat thought that vested interests who wished to get privileges from the state cloaked their naked self interest by using deception, trickery, or fraud ("la ruse") in order to confuse and distract the people at whose expence these privileges were granted.

31 By "Utopian" Molinari hand in mind socialist utopian thinkers such as Fourier or Cabet. Ironically, Molinari was also accused by his economist colleagues of "utopianism" especially over his ideas of the private "production of security" which he advocated in an article in the JDE and in the "11th Soirée" of this book. He seems to anticipate this in his remarks in the preface. Also note that he referred to himself as "le rêveur" (the dreamer) in an anonymous article published in the JDE on the eve of the June Days uprising in Paris in 1848 in which he appealed to socialists to support each other since they shared some ideas on exploitation and injustice. See footnote below, p. ??? [See glossary entry on "Utopia" .]

32 Louis Blanc was a journalist and historian who was active in the socialist movement. During the 1848 Revolution he became a member of the Provisional Government, promoted the National Workshops, and supported "right to work" legislation. [See glossary entry on "Blanc" .]

33 Unlike the Conservative, Molinari was probably not a practicing Catholic. He uses the word "Dieu" (God) 28 times in the book but most of these are exclamations like "God forbid!" or similar; the word "Providence" 10 times, and the word "Créateur" (Creator) 8 times. Since he does not mention the sacraments or any doctrinal matter it is most likely that he was a deist of some kind who believed that an "ordonnateur des choses" (the organizer of things) created the world and the laws which governed its operation (see note 305, p. 269 in Soirée 10). However, Molinari also believed in the afterlife and thought it was an essential incentive to forgo immediate pleasures in this life in order to achieve "superior" pleasures in the next. This was especially important when it came to the issue of controlling the size of one's family. Molinari thought the solution to the Malthusian population growth problem was the voluntary exercise of "moral restraint" (he uses the English phrase) in a society where complete "liberty of reproduction" existed. What made moral restraint possible was a moral code where religious values played a key role. In the Introduction to the Cours d'économie politique (2nd ed. 1864), vol. 1 Molinari states that "Therefore, political economy is an essentially religious science in that it shows more than any other the intelligence and the goodness of Providence at work in the superior government of human affairs. Political economy is an essentially moral science in that it shows that what is useful is always in accord in fact with what is just. Political economy is an essentially conservative science in that it exposes the inanity and folly of those theories which tend to overturn social organization in order to create an imaginary one. But the beneficial influence of political economy doesn't stop there. Political economy does not only come to the aid of the religion, the morality, or the political conservation of societies, but it acts even more directly to improve the situation of the human race." [Gustave de Molinari, Cours d'Economie Politique (Paris: Guillaumin, 1863). 2 vols. 2nd revised edition. Vol. 1. Chapter: INTRODUCTION. </titles/818#Molinari_0253-01_54>.] Nevertheless, Molinari was very critical of organized religion, especially the monopoly of religion which had emerged in Europe, the political privileges of religious corporations, and any form of compulsory religion. He shared the views of his friend and colleague Frédéric Bastiat who argued that "theocratic plunder" was one of the main forms of political and economic injustice before the Revolution. [See, Frédéric Bastiat, Economic Sophisms , trans. Arthur Goddard, introduction by Henry Hazlitt (Irvington-on-Hudson: Foundation for Economic Education, 1996). Second Series, Chapter 1: The Physiology of Plunder. < /titles/276#lf0182_head_056 >. Or, Bastiat's Collected Works (Liberty Fund),pp. ??? forthcoming.] Molinari returned to the issue of religion 40 years later in a book length historical and sociological analysis of the overall benefits of religion to human progress. [See, Molinari, Religion (Paris: Guillaumin, 1892) which was translated into English by Walter K. Firminger (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1894). Two years later he wrote another on Science et religion (Paris: Guillaumin, 1894).]

34 Molinari's close friend and colleague Frédéric Bastiat regarded the argument that free market ideas were correct in theory but impractical to apply, and that there were no "absolute principles" which should guide government policies, as one of the major fallacies he had to refute in his collection of Economic Sophisms which he wrote between 1845 and 1850. See in particular "There are no Absolute Principles" in Series I (1846), in Bastiat's Collected Works , vol. 3 (Liberty Fund, forthcoming).

35 Joseph de Maistre (1753-1821) was a conservative political thinker who supported the Old Regime notion of "throne and altar". [See the glossary entry on "Maistre." ]

36 "The Constitution of 1795, like all the previous ones, was made for man . Now, there (is) no man in the world. In my lifetime I have seen Frenchmen, Italians, Russians, and so on; I even know, thanks to Montesquieu, that one can be Persian . But as for man , I declare not to have met one in my life. If he exists, it is certainly unknown to me." In Oeuvres du comte J. de Maistre. Tome Premier: Considérations sue la France, Essais sue le Principe générateur des Constitutions politiques (Lyon: J.-B. Pelagaud, 1851). Nouvelles Édition, p. 88.

37 See Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, The Complete Works of M. de Montesquieu(London: T. Evans, 1777), 4 vols. Vol. 1. BOOK XIV.: OF LAWS AS RELATIVE TO THE NATURE OF THE CLIMATE. < /titles/837#lf0171-01_label_1040 >.

38 "That is droll justice which is bounded by a stream! Truth on this side of the Pyrenees, error on that." "Of Justice, Customs and Prejudices" in The Thoughts of Blaise Pascal , translated from the text of M. Auguste Molinier by C. Kegan Paul (London: George Bell and Sons, 1901). < /titles/2407#Pascal_1409_371 >.

39 The Navigation Acts were a lynch pin of the British policy of mercantilism from its introduction in 1651 to its abolition in 1849. They were designed to protect British merchant shipping from competition by third parties, in particular the Dutch and the French. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 and the Navigation Acts in 1849 were vital for the development of a policy of free trade in Britain. See the glossary entries on "The Navigation Acts" and "The Anti-Corn Law League."

40 Richard Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League were successful in getting the British Parliament to repeal the protectionist Corn Laws in January 1846.

41 Molinari discusses intellectual property at greater length in Soirée no. 2 below.

42 The right to a legally determined, prior compensation for property confiscated by the state was enshrined in the Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen in June 1791 (Article 19) and in the Civil Code of 1804 (articles 544 and 545). The Law of 8 March 1810 established tribunals for the purpose of determining the amount of compensation payments. The Law of 7 July 1833 (and amended by the Law of 6 May 1841) created special juries of local landowners which would determine the level of compensation for confiscated land. [See, A. Legoyt, "Expropriation pour cause d'utilité publique," DEP , vol. 1, pp. 751-53.]

43 In the 1848 Budget a total of fr. 39.6 million was set aside for expenditure by the state on religion. Of this 38 million went to the Catholic Church, 1.3 million went to Protestant churches, and 122,883 went to Jewish groups. See the Appendix on French Government Finances 1848-49.

44 Molinari uses the phrase "réorganisateurs de la société" and has in mind the arguments of the socialists Louis Blanc, Charles Fourier, and their followers.

45 Charles Fourier (1772-1837) was a utopian socialist thinker who founded a school of thought which advocated the idea that people should live together as one family and hold property in common. [See glossary entries on "Fourier" and "Phalanstery " .]

46 A biblical word used for weeds. See "the parable of the tares of the field" in Matthew 13: 36.

47 The Conservative is referring to the declaration of a state of siege (martial law) on 24 June 1848 under General Cavaignac following the attempted coup on 15 May by Louis Blanc and other left wing Deputies and the rioting of protesters during the June Days in protest at the closure of the National Workshops. Many hundreds of rioters were killed by the troops and some 15,000 were arrested, of which about 4,000 were transported to Algeria. The Political Clubs of Paris and the radical press were also shut down.

48 But Molinari had. He wrote an article on "Saint-Pierre" and "Peace" for the DEP, vol. 2, pp. 565-66, pp. 307-14, and a book on Saint-Pierre's ideas during the Crimean War, Gustave de Molinari, L'abbé de Saint-Pierre, membre exclu de l'Académie française, sa vie et ses oeuvres (Paris: Guillaumin, 1857). Charles Irénée Castel, Abbé de Saint-Pierre (1658-1743) was a French cleric and reformer who advocated a plan to create a pan-European tribunal to adjudicate international disputes instead of waging war: Projet pour render la paid perpétuelle en Europe (1713-17). His writings influenced Rousseau and predated Kant's thinking on perpetual peace. [See glossary entry on "Saint-Pierre." ]

49 See Molinari's impassioned plea for liberty in the closing paragraphs of S12 where he contrasts liberty and the oppressed such as the slaves of Spartacus. The issue of slavery and serfdom was one to which Molinari gave considerable attention in the 1840s. He published on the abolition of slavery in the French colonies in 1846, he wrote the long bibliographic article on slavery in the DEP , "Esclavage," vol. 1, pp. 712-31 as well as a shorter article on serfdom, "Servage" , DEP , vol. 2, pp. 610-13. In the latter he concluded that serfdom was "a vestige of a barbarous epoch" and that it would inevitably disappear. [See Études économiques. L'Organisation de la liberté industrielle et l'abolition de l'esclavage (1846).] Given his deep interest in slavery and serfdom Molinari leapt at the chance to visit Russia at the invitation of Alexander II to give some lectures on political economy. Molinari spent 4 months traveling in Russia from February to July 1860, on the eve of the emancipation of the serfs in February 1861. [See, Molinari, Lettres sur la Russie (Bruxelles: A. Lacroix, Verboeckhoven et Cie, 1861. Second edition Paris: E. Dentu, 1877).]

50 The socialists were not the only ones to have set up political clubs during the Revolution to discuss radical ideas. The classical liberal economists also had a Club, "le club de la liberté du travail" , which was set up by Charles Coquelin on 31 March 1848 specifically to combat socialist ideas about the "right to work." One of its best public speakers was Alcide Fonteyraud (1822-1849) who died in the cholera epidemic which swept France in 1849. Molinari visited many of the political clubs with Coquelin to hear first hand what was being discussed and possibly also to engage the speakers in open debate. He did exactly the same thing during the Revolution of 1870 which resulted in a vivid account of "les Clubs rouges" (the socialist Clubs). Molinari's account of the 1848 Revolution and the coming to power of Napoleon can be found in Les Révolutions et le despotisme envisagés au point de vue des intérêts matériel . (Brussels: Meline, 1852). See also Molinari, Les Clubs rouges pendant le siège de Paris(Paris: Garnier Freres, 1871) and, Le Mouvement socialiste et les réunions publiques avant la révolution du 4 septembre 1870 (Paris: Garnier Freres, 1872). See Minart, p. 74.

51 [See the glossary entries for "Press (Conservative)," "Press (Liberal)," and "Press (Socialist)" .]

52 The capital of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople, was besieged for 4 days as part of the 4th Crusade in 1204. After the city fell it was looted by the Christian Crusaders. Among many other things, the great Imperial Library was destroyed.

53 The Socialist is making fun of the fact that the Economists had only the Political Economy Society, the Journal des Économistes , and the Guillaumin publishing firm which were all organized by the same small number of individuals. Whereas the socialists had many organisations and journals which had emerged during the 1830s and 1840s. [See the glossary entries on these organizations.]

54 Henri Saint-Simon developed a theory of social and economic organization in the late 1810s and 1820s which advocated rule by a technocratic elite of "industrialists" and managers. This differed from similar liberal ideas about "industry" which emerged at the same time by Thierry and Dunoyer in that the liberals advocated no government regulation, whereas the Saint-Simonian view verged on being a form of state directed socialism. [See the glossary entry on "Saint-Simon," "Industry vs.Plunder" , and "Thierry" .]

55 The socialist Charles Fourier (1772-1837) believed that a more just and productive society would be one which was based on the common ownership of property and the communal organization of all productive activity. The organization base of his new society was the "Phalanstery" which was the name of the specially designed building which would house 1,600 people. Some utopian communities based on his idea were established in North America. [See the glossary entries on "Fourier" and "Phalanstery." ]

56 The socialist probably has in mind Fourier's views on marriage. Charles Fourier believed that marriage was a form of oppression for women and advocated an end to "le mariage exclusif" (marriage to one person) and "le mariage permanent" (indissoluble marriage) in favour of either no marriage at all or what he referred to as "la corporation amoureux" which today might mean something like an open marriage. See Oeuvres complètes de Charles Fourier, tome 1. Théorie des quatres mouvements , 3rd ed. (Paris: La Librairie Sociétaire, 1846), p. 89..

57 Étienne Cabet was a lawyer and utopian socialist who coined the word "communism." He advocated a society in which the elected representatives controlled all property that was owned in common by the community. In 1848 Cabet left France in order to create such a community (called "Icarie") in Texas and then at Nauvoo, Illinois, but these efforts ended in failure. [See the glossary entry on "Cabet." ]

58 Philippe Mathé-Curtz ("Curtius") (1737-1794) was a Swiss doctor and sculptor who created wax figures for anatomical study. He later began creating portraits of famous people after he moved to Paris in 1765, when his figure of Madame du Barry (the mistress of King Louis XV) caused a sensation. Curtius opened a museum to the public in 1770 which was moved to the Palais-Royal in 1776. In the late 1770s he made figures of people like Voltaire, Rousseau, and Benjamin Franklin. In 1794 he bequeathed his collection of wax figures to the daughter of his housekeeper, Marie, who in 1795 married M. Tussaud.

59 Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was a political theorist considered to be the father of anarchism. He is best known for writing Qu'est-ce que la propriété? (1841) (his answer was that "property is theft"). He engaged in a spirited debate with Bastiat on the justice of credit and charging interest. The liberal publishing firm Guillaumin published two books by Proudhon which seems a little odd given the fact that he was a left-anarchist. A two volume work appeared in 1846 called Système des contradictions économiques, ou, Philosophie de la misère , 2 vols. (System of economic contradictions, or the philosophy of misery), which Molinari reviewed in the JDE T. 18, N° 72, Novembre 1847, and another in 1850 (which is more understandable as Bastiat was one of the authors) Gratuité du crédit, discussion entre M. Fr. Bastiat et M. Proudhon (Free Credit: A discussion between Bastiat and Proudhon). [See the glossary entry on "Proudhon." ]

60 Proudhon opposed the charging of interest and advocated a system of Exchange Banks (Banques d'échange) or People's Banks which would offer low interest rate loans to workers. After the February Revolution of 1848 broke out Proudhon attempted to set up such a bank. He applied for an act of incorporation in January 1849 but was not able to raise the capital of fr. 50,000 it needed. Proudhon and Bastiat had a famous debate on "Free Credit" in October 1849 to March 1850. See Bastiat, Collected Works , vol. 4 (Liberty Fund, forthcoming) and Gratuité du crédit. Discussion entre M. Fr. Bastiat et M. Proudhon [Free Credit. A Discussion between M. Fr. Bastiat and M. Proudhon] (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850). [See the glossary entry on "Proudhon" and "Money and Banking." ]

61 See the long and very detailed entry by Louis Reybaud, "Socialistes, Socialisme," in DEP , vol. 2, pp. 629-41. He provides a comprehensive examination of the different schools of French socialist thought and an excellent bibliography of their writings. Reybaud also wrote a 2 volume work on modern socialism which first appeared in 1840 and was in its 6th edition by 1849. [See, Louis Reybaud, Études sur les réformateurs ou socialistes modernes. 6e édition, précédée du rapport de M. Jay et de celui de M. Villemain, (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849). Glossary entry "Press (Socialist)" .]

62 Molinari is referring to the February Revolution of 1848 which overthrew the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe and introduced the Second Republic. [See the glossary entry on the "Revolution of 1848." ]

63 On Molinari's view of the natural laws which govern economics, see note 3 of the preface.

64 The issue of whether or not men are "free and active beings" or more like reactive "plants and animals" was debated vigorously when it came to the question of population growth and Malthusian limits to such growth. [See, Soirée 10, footnote 311, p. 274.]

65 One of the key beliefs which distinguishes the French school of political economy from the English school is the grounds they had for believing in property. The English were strongly utilitarian in that they thought the institution of property was generally beneficial to human progress and prosperity but that the government might be justified in sometimes limiting property "rights" of individuals for the benefit of the broader society. The French Economists believed in property rights on the grounds of natural law and were more doctrinaire in defending individual property rights against encroachments by the state. [See, Léon Faucher, "Propriété," DEP , vol. 2, pp. 460-73 for an overview of the thinking of the Economists on property; and Charles Comte's Traité de la propriété (1834) which was very influential on their thinking.] Molinari wrote a much longer treatment of his ideas on property in Lesson 4 "Value and Property" in the second and revised edition of the Cours d'économie politique(1863), pp. 107-31. Here he categorizes property into 6 major types, each of which has its own corresponding kind of liberty. [See, the Appendix on Molinari and the Different Types of Liberty.]

66 Several times in this section Molinari describes man as an "active and free being", a person who "acts" in order to achieve the goals he sets himself. It seems Molinari is trying to generalize about economic behaviour and is toying with what in the 20th century would become known as the Austrian theory of "human action" which was developed by the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973) in Human Action (1949). Bastiat was doing something very similar in his innovative use of "Crusoe economics" to discuss the economic choices faced by an individual like Robinson Crusoe on the Island of Despair. [See, Ludwig von Mises, Human Action: A Treatise on Economics , in 4 vols., ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2007).</titles/1892>. See also some of Bastiat's later Economic Sophisms and Economic Harmonies where he develops his ideas on Crusoe economics in some detail.

67 In early 1847 Frédéric Bastiat used the character of Robinson Crusoe marooned on his island as part of a thought experiment to explore in a very abstract way how individuals went about making their economic plans and choices in the face of scarcity. In a couple of essays in Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848) and in his unfinished magnum opus Economic Harmonies (1850) Bastiat became the first economist to do this kind of quite modern economic analysis. Molinari was no doubt aware of this new approach to thinking about economics and hints about it here and uses it explicitly a bit later in a chapter on "L'Échange et la valeur" (Exchange and Value) in the 1st edition of Cours d'économie politique (1855), vol. 1, pp. 89-92. He also repeats the example in the expanded chapter "La Valeur et le prix" in the 2nd edition of Cours d'économie politique (1863). [See, Frédéric Bastiat, Economic Sophisms , trans. Arthur Goddard, introduction by Henry Hazlitt (Irvington-on-Hudson: Foundation for Economic Education, 1996). Second Series, Chapter 14: Something Else. < /titles/276#lf0182_head_082 > also in Collected Works , vol. 3 (Liberty Fund, forthcoming); and Gustave de Molinari, Cours d'Economie Politique (Paris: Guillaumin, 1863). 2 vols. 2nd revised edition. Vol. 1. TROISIÈME LEÇON: la valeur et le prix. < /titles/818#lf0253-01_head_010 >, pp. 86-88 in the printed edition.]

68 In the original French Molinari uses exactly the same phrasing as the title to Proudhon's book, Qu'est-ce que la propriété? (What is Property?) (1841), but of course comes to the opposite position in his answer.

69 Molinari uses the word "séparé" (separated from one's self) which might be translated as "alienated" but as this has a strong Marxist connotation we have avoided using it in this context.

70 See Molinari's long extract by Leclerc on external property in the Addenda [from Journal des Économistes , 15 October, 1848]. Molinari makes a distinction between two different kinds of property here - "la propriété intérieure" (internal or personal property, or "self-ownership") and "la propriété extérieure" (external property, i.e. property which lies outside or is external to one's body): "The first consists in the right every man has to dispose of his physical, moral and intellectual faculties, as well as of the body which both houses those faculties and serves them as a tool. The second inheres in the right every man has over that portion of his faculties which he has deemed fit to separate from himself and to apply to external objects." [ Les Soirées , p. ???, Economist's opening remark at the beginning of Soirée 2].