Locke on Toleration by Eric Mack

Eric Mack, "Locke on Toleration: Locke’s A Letter Concerning Toleration"

Source: This essay was written by Dr. Eric Mack, Professor of Philosophy, Tulane University.

Copyright: The electronic rights to the essay are held by Liberty Fund, Inc.

Fair Use: This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

See also:

- Reading List: Eric Mack's "Introduction to the Political Thought of John Locke"

- John Locke's main page in the OLL

- Two Treatise of Government

- Locke, Four Letters concerning Toleration

- LF's edition of A Letter concerning Toleration (2010)

Introduction

The two most famous and widely read books in political philosophy by the great English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) are his Two Treatises on Government and his A Letter Concerning Toleration. Both were published in 1689 in the wake of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 which brought William, Prince of Orange and his wife Mary to the English throne in place of skedaddling James II. (The Letter was composed around 1685 while Locke was in exile in Holland.)

In the second book of the Two Treatises, Locke lays out his strongly individualist form of liberalism. He argues for the natural rights of life, liberty, and property and for the legitimacy of government which is more or less limited in its function to the protection of these natural rights. He defends forcible resistance against political rulers who violate these rights or seek to undermine the governmental structures which has been established to better protect these rights.

Although freedom of religious practice fits very comfortably within Locke's capacious conception of liberty, it is not mentioned at all within Locke's general statement of his pro-liberty doctrine. No doubt one reason for the omission of the case for religious toleration from the general treatise was that there was a long tradition of people writing separate essays either in support of governmental enforcement of religious conformity or in support of religious toleration. Locke is very much a part of that tradition.

In addition, however, Locke had a particular goal in writing the Two Treatises of Government, viz., to garner support for resistance to Charles II and his bother James (the future James II). If Locke had made explicit the link between the cause of toleration and the cause of resistance to these monarchs, individuals who were not friends of toleration would not be drawn to the cause of resistance. It was better strategy to defend toleration in a separate work -- even if Locke did not publically attach his name to either work.

A Letter Concerning Toleration

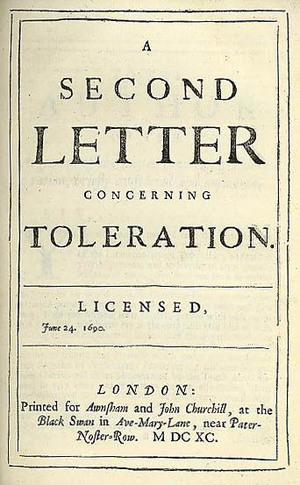

IntroductionJonas Proast wrote an interesting and challenging response to Locke's first letter concerning toleration. This initiated an intriguing but almost interminable exchange between Locke and Proast. Eventually each wrote three increasing lengthy letters -- Locke's third "letter" runs for 405 pages in his collected works -- and Locke was busy on his fourth letter when he died in 1704. This brief look at Locke on toleration attends only to the first and most famous of Locke's letters on toleration.

[To read all of Locke's letters on toleration see John Locke, The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes, (London: Rivington, 1824 12th ed.). Vol. 5.]

Crucial Arguments and Passages from Locke’s A Letter Concerning TolerationThe initial framework for Locke’s defense of religious toleration is the general political doctrine which he develops and defends in his Second Treatise of Government. Governments exist to defend the rights which individuals have over their persons, lives, liberties, and estates. The legitimate use of force – by individuals or government – is limited to the function of protecting and enforcing these rights. As long as someone’s religious beliefs and practices do not trespass upon the rights of others, the magistrate has no authority to suppressing or punish those beliefs or practices.

It is the duty of the civil magistrate, by the impartial execution of equal laws, to secure unto all the people in general, and to every one of his subjects in particular, the just possession of these things belonging to this life… But seeing no man does willingly suffer himself to be punished by the deprivation of any part of his goods, and much less of his liberty or life, therefore is the magistrate armed with the force and strength of all his subjects, in order to the punishment of those that violate any other man’s rights.

…the pravity of mankind being such, that they had rather injuriously prey upon the fruits of other men’s labours, than take pains to provide for themselves; the necessity of preserving men in the possession of what honest industry has already acquired, and also of preserving their liberty and strength, whereby they may acquire what they farther want, obliges men to enter into society with one another that by mutual assistance and joint force, they may secure unto each other their properties, in the things that contribute to the comforts and happiness of this life…

Within the argument of the Second Treatise Locke does not explicitly consider the fact – as Locke and his contemporaries see it – that man’s most fundamental concern is for salvation. But, in a work on religious toleration, Locke has to consider whether individuals who are deeply concerned for their salvation would confer upon the magistrate authority to use coercion for the salvation of their souls or the souls of others. Would this concern for salvation lead individuals to confer a more extensive authority for rulers than is envisioned in the Second Treatise? Many of Locke’s arguments in A Letter Concerning Toleration are designed to show that, even when individuals focus on this fundamental concern for salvation, they will not broaden the authority which they confer upon the magistrate. Other points by Locke are responses to anticipated objections against his arguments.

Locke provides a series of arguments to show that no individual would rationally authorize the magistrate to use force or the threat of force against himself (i.e., the authorizer):

First, no one can unconditionally authorize anyone to decide religious matters for him.

… no man can so far abandon the care of his own salvation, as blindly to leave it to the choice of any other, whether prince or subject, to prescribe to him what faith or worship he shall embrace.

Second, the magistrate’s use of force cannot produce the inward persuasion which is necessary to salvation.

The care of souls cannot belong to the civil magistrate, because his power consists only in outward force: but true and saving religion consists in the inward persuasion of the mind, without which nothing can be acceptable to God. And such is the nature of the understanding, that it cannot be compelled to the belief of any thing by outward force. Confiscation of estate, imprisonment, torments, nothing of that nature can have any such efficacy as to make men change the inward judgment that they have framed of things.

Third, the magistrate is not more likely to have the truth than the individual subject. For magistrates are not especially good seekers of the truth. Moreover, a magistrate who suppresses religious dissent is less likely to have the truth than a subject who lives in a realm in which religious beliefs can be freely debated. For truth is most likely to be found when it is allowed to shift for itself.

For, there being but one truth, one way to heaven; what hopes is there that more men would be led into it, if they had no other rule to follow but the religion of the court, and were put under a necessity to quit the light of their own reason, to oppose the dictates of their own consciences, and blindly to resign up themselves to the will of their governors, and to the religion which either ignorance, ambition, or superstition had chanced to establish in the countries where they were born?

… for truth certainly would do well enough, if she were once made to shift for herself. She seldom has received, and I fear never will receive, much assistance from the power of great men, to whom she is but rarely known, and more rarely welcome. She is not taught by laws, nor has she any need of force to procure her entrance into the minds of men. Errours indeed prevail by the assistance of foreign and borrowed succours. But if truth makes not her way into the understanding by her own light, she will be but the weaker for any borrowed force violence can add to her

Locke also argues that no one may legitimately authorize the magistrate to use coercion against other individuals on the grounds that this coercion would be good for those individuals. Locke draws out the implication of his view that each has ultimate moral authority over himself by insisting that even if the magistrate’s forcible intervention would benefit me, if I have not agreed to that intervention, the magistrate may not intervene. Locke finds it preposterous that people in general recognize that individuals have the right to go their own foolish ways in worldly matters but refuse to recognize that individuals also have the right to go their own foolish ways in extra-worldly matters.

In private domestic affairs, in the management of estates, in the conservation of bodily health, every man may consider what suits his own conveniency, and follow what course he likes best. No man complains of the ill management of his neighbour’s affairs. No man is angry with another for an errour committed in sowing his land, or in marrying his daughter. No-body corrects a spendthrift for consuming his substance in taverns. Let any man pull down, or build, or make whatsoever expences he pleases, no-body murmurs, no-body controls him; he has his liberty. But if any man do not frequent the church, if he do not there conform his behaviour exactly to the accustomed ceremonies, or if he brings not his children to be initiated in the sacred mysteries of this or the other congregation; this immediately causes an uproar, and the neighbourhood is filled with noise and clamour. Every one is ready to be the avenger of so great a crime. And the zealots hardly have patience to refrain from violence and rapine, so long till the cause be heard, and the poor man be, according to form, condemned to the loss of liberty, goods or life.

Indeed, Locke insists that, just as each individual is responsible for his own economic and medical decisions, each is responsible for his own salvation.

But what if he neglect the care of his soul? I answer, what if he neglect the care of his health, or of his estate; which things are nearlier related to the government of the magistrate than the other? Will the magistrate provide by an express law, that such an one shall not become poor or sick? Laws provide, as much as is possible, that the goods and health of subjects be not injured by the fraud or violence of others; they do not guard them from the negligence or ill-husbandry of the possessors themselves. No man can be forced to be rich or healthful, whether he will or no. Nay God himself will not save men against their wills.

Why are people so quick to avenge the crime of deviation in religion? Perhaps it is because the zealots have learned that, by pretending a love of the truth, they can successfully prey upon and achieve temporal domination over the dissidents.

…whilst they pretend only love for the truth, this their intemperate zeal, breathing nothing but fire and sword, betray their ambition, and show that what they desire is temporal dominion. For it will be very difficult to persuade men of sense, that he, who with dry eyes, and satisfaction of mind, can deliver his brother unto the executioner, to be burnt alive, does sincerely and heartily concern himself to save that brother from the flames of hell in the world to come.

Another possible basis for governmental action against those who are judged to be heterodox is that the beliefs or practices of the heterodox are sinful and that the magistrate’s authority extends to the suppression of sin. However, Locke strikingly rejects the latter premise.

But idolatry, say some, is a sin, and therefore not to be tolerated. If they said it were therefore to be avoided, the inference were good. But it does not follow, that because it is a sin it ought therefore to be punished by the magistrate. For it does not belong unto the magistrate to make use of his sword in punishing every thing, indifferently, that he takes to be a sin against God. Covetousness, uncharitableness, idleness, and many other things are sins, by the consent of all men, which yet no man ever said were to be punished by the magistrate. The reason is, because they are not prejudicial to other men’s rights, nor do they break the public peace of societies.

Two important features of Locke’s stance on religious liberty should to be noticed. First, there is no special case for or against religious liberty. Religious liberty, like all liberty, is simply a matter of being allowed to dispose of one’s persons and one’s possessions as one sees fit. If I may consume my bread and wine while entertaining my house guests, I may consume my bread and wine in a religious ritual. If I may not consume your calf while entertaining my friends, I may not consume your calf in a religious ritual. In all cases, what matters is whose bread and wine, whose calf, is being consumed. What matters is whether I am minding my own business or your business. Second, as we have already seen, religious liberty – just as liberty at large – rests on an identification of who has rights over, i.e., who has property in, what.

You will say, by this rule, if some congregations should have a mind to sacrifice infants, or, as the primitive christians were falsely accused, lustfully pollute themselves in promiscuous uncleanness, or practise any other such heinous enormities, is the magistrate obliged to tolerate them, because they are committed in a religious assembly? I answer, No. These things are not lawful in the ordinary course of life, nor in any private house; and therefore neither are they so in the worship of God, or in any religious meeting. But indeed if any people congregated upon account of religion, should be desirous to sacrifice a calf, I deny that that ought to be prohibited by a law. Meliboeus, whose calf it is, may lawfully kill his calf at home, and burn any part of it that he thinks fit. For no injury is thereby done to any one, no prejudice to another man’s goods. And for the same reason he may kill his calf also in a religious meeting. Whether the doing so be well-pleasing to God or no, it is their part to consider that do it

No refrain is more constant throughout Locke’s letters on toleration than that every man and every church is orthodox to itself. The main purpose of this refrain in Locke is to counter the proposal that only those magistrates who hold to the true religion may coerce religious belief or practice. Locke’s counter is that all magistrates (and all churches and individuals) take themselves to have the religious truth and, hence, every magistrate who hears the maxim “enforce your religious beliefs but only if they are true” will thereby take himself to be authorized to enforce his beliefs. Hence, according to Locke, one cannot limit who gets to enforce religious beliefs and one cannot avoid constant armed conflict over religion by telling people that only the orthodox view may be enforced. The only way to limit enforcement and avoid constant armed conflict is to hold that religious beliefs and practices, no matter how true or righteous, are never to be enforced.

For every church is orthodox to itself; to others, erroneous or heretical. Whatsoever any church believes, it believes to be true; and the contrary thereunto it pronounces to be errour.

Locke endorses full toleration for all Protestant sects, for Jews, Muslims, and pagans. Nevertheless, there are certain limits on religious liberty. Toleration is not to be extended to individuals whose religious beliefs or affiliations directly endanger people in their peaceful enjoyment of their rights. Those who themselves reject toleration or maintain that only members of their religion have a right to rule are not to be tolerated. Those whose religious affiliation places them under a foreign prince and those who believe that they are not bound to keep their pledges to members of other religions are not to be tolerated. On the last two grounds, Catholicism is not to be tolerated. And on the last ground, atheism is not to be tolerated since, according to Locke, those who do not believe in divine reward and punishment can not be trusted to keep their promises.

That church can have no right to be tolerated by the magistrate, which is constituted upon such a bottom, that all those who enter into it, do thereby ipso facto deliver themselves up to the protection and service of another prince. For by this means the magistrate would give way to the settling of a foreign jurisdiction in his own country, and suffer his own people to be listed, as it were, for soldiers against his own government

Those are not at all to be tolerated who deny the being of God. Promises, covenants, and oaths, which are the bonds of human society, can have no hold upon an atheist.

Let us consider one final argument of Locke’s which nicely epitomizes his view about the relative merits of oppression versus liberty. This is his response to the argument that religious dissidents should be severely monitored or punished because whenever they get together they grumble and plan resistance against the government. Locke’s response is that, of course, these people grumble and plan resistance precisely because they are oppressed. The solution is not more oppression but liberty. Just as complex and mutually advantageous economic order derives from liberty, i.e., each individual’s freedom to dispose of his person and possessions as he sees fit, so too does complex and mutually beneficial religious order derives from liberty.

…let those dissenters enjoy but the same privileges in civils as his other subjects, and he will quickly find that these religious meetings will be no longer dangerous. For if men enter into seditious conspiracies, it is not religion inspires them to it in their meetings, but their sufferings and oppressions that make them willing to ease themselves. Just and moderate governments are every-where quiet, every-where safe. But oppression raises ferments, and makes men struggle to cast off an uneasy and tyrannical yoke. …there is one thing only which gathers people into seditious commotions, and that is oppression.

It is not the diversity of opinions, which cannot be avoided; but the refusal of toleration to those that are of different opinions, which might have been granted, that has produced all the bustles and wars, that have been in the christian world, upon account of religion.