Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics Vol. 7 (1650-1660) (2nd ed)

Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics, Volume 7 (1650-60) (2nd revised and enlarged edition)

[Note: This is a work in progress]

Revised: 27 May, 2018.

Note: As corrections are made to the files, they will be made here first (the “Pages” section of the OLL </pages/leveller-tracts-summary>) and then when completed the entire volume will be added to the main OLL collection (the “Titles” section of the OLL) </titles/2595>.

- Tracts which have not yet been corrected are indicated [UNCORRECTED] and the illegible words are marked as &illegible;. Some tracts have hundreds of illegible words and characters.

- As they are corrected against the facsimile version we indicate it with the date [CORRECTED - 03.03.16]. Where the text cannot be deciphered it is marked [Editor: illegible word].

- When a tract is composed of separate parts we indicate this where possible in the Table of Contents.

For more information see:

- Summary of the Leveller Tracts Project </pages/leveller-tracts-summary>

- The Complete Table of Contents </pages/leveller-tracts-table-of-contents>

Table of Contents

-

Introductory Matter (to be added later)

- Introduction to the Series

- Publishing and Biographical Information

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

-

Editorial Matter (to be added later)

- Editor’s Introduction to Volume 7 (1650-60)

- Chronology of Key Events

- Tracts in Volume 7 (1650-60) [1,055 illegibles)

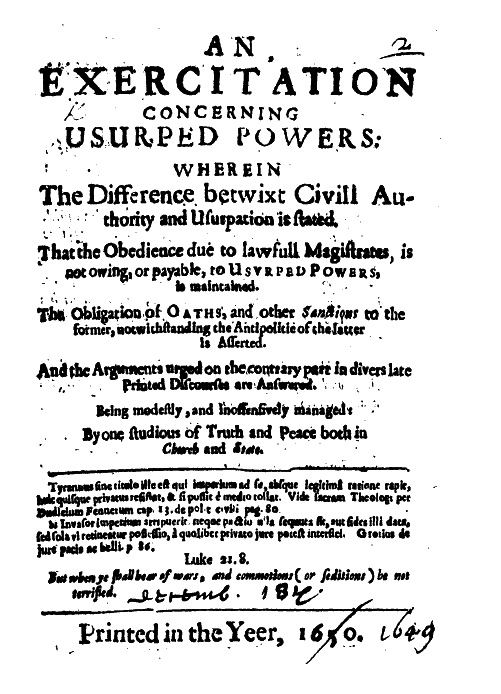

- [CORRECTED - 09.05.2018 - 243 illegibles] [Move to vol. 6???] T.216 (7.1) Richard Hollingworth, An Exercitation concerning Usurped Powers (18 December, 1649/1650).

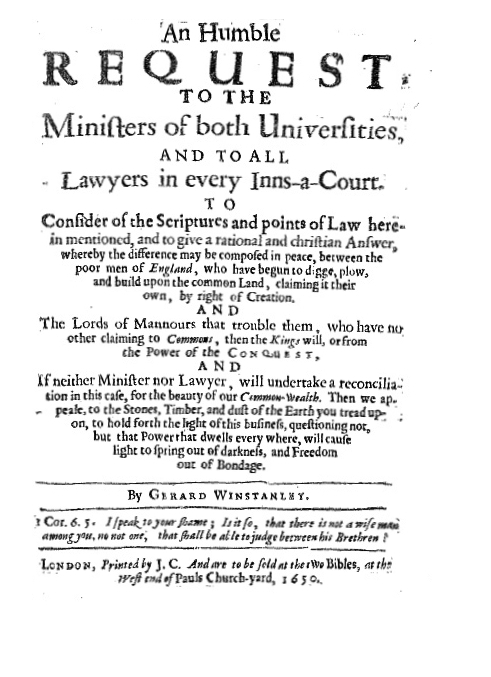

- [CORRECTED - 11.09.2017 - 2 illegibles] T.217 (7.8) Gerrard Winstanley, An Humble Request, to the Ministers of both Universities (9 April, 1650).

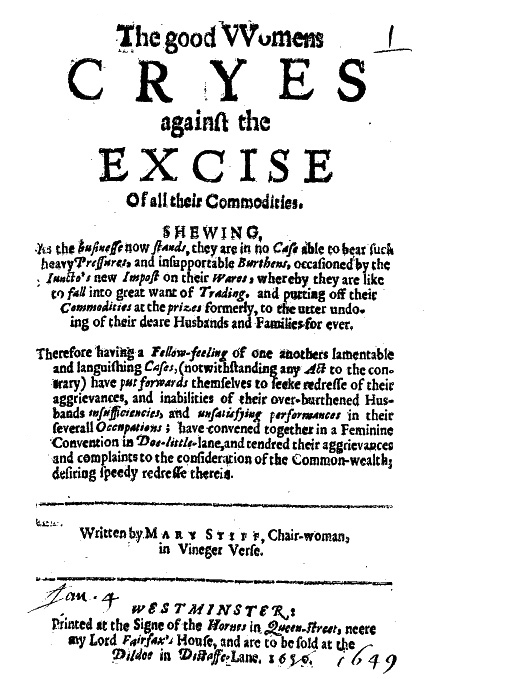

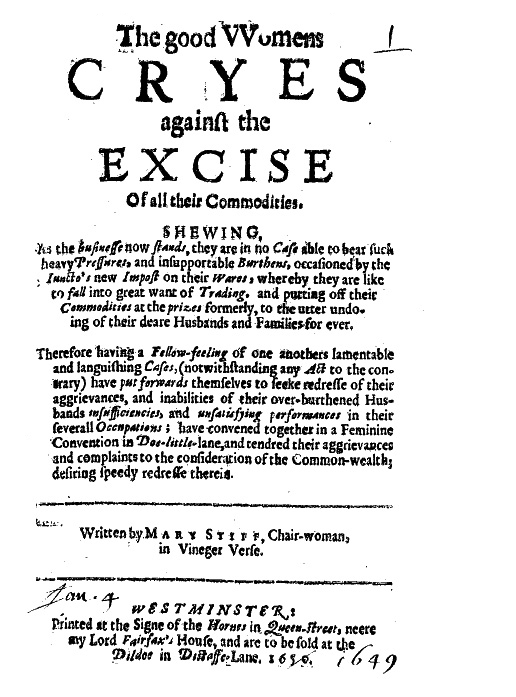

- [CORRECTED - 07.11.2017 - 4 illegibles] T.218 (7.2) Mary Stiff, The good Womens Cryes against the Excise of all their Commodities (4 January, 1650).

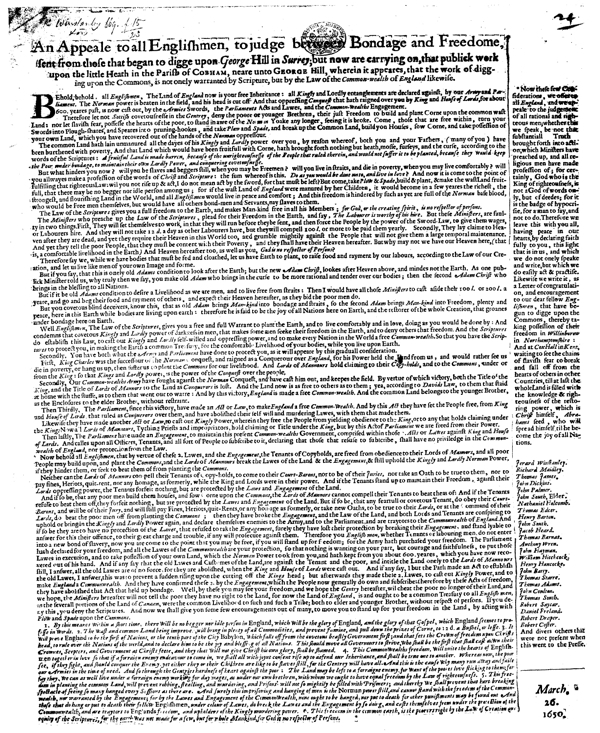

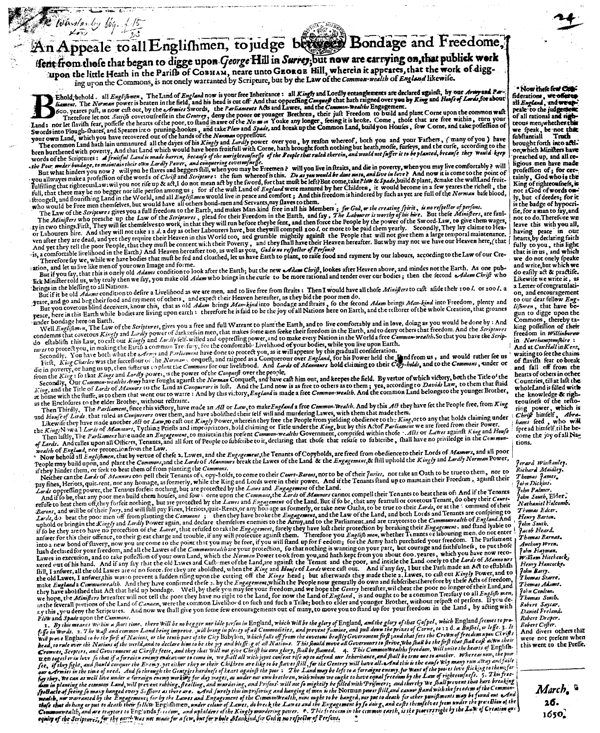

- [CORRECTED - 07.11.2017 - 4 illegibles] T.219 (7.3) Gerard Winstanley, An Appeale to all Englishmen (26 March, 1650).

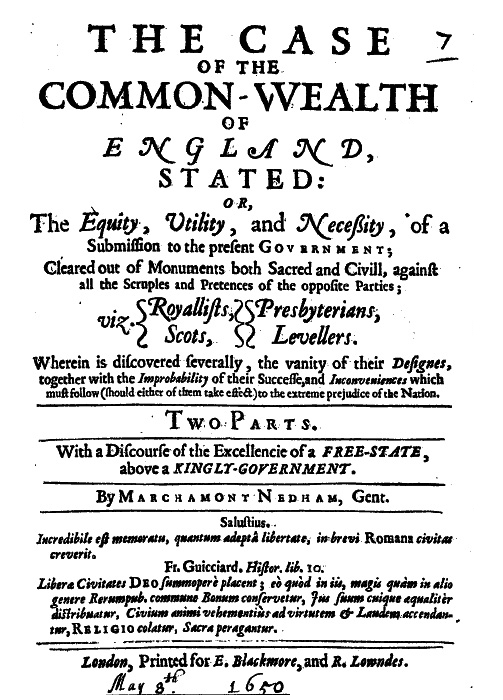

- [CORRECTED - 08.11.2017 - 53 illegibles] T.220 (7.4) Marchamont Nedham, The Case of the Common-wealth of England stated (8 May, 1650).

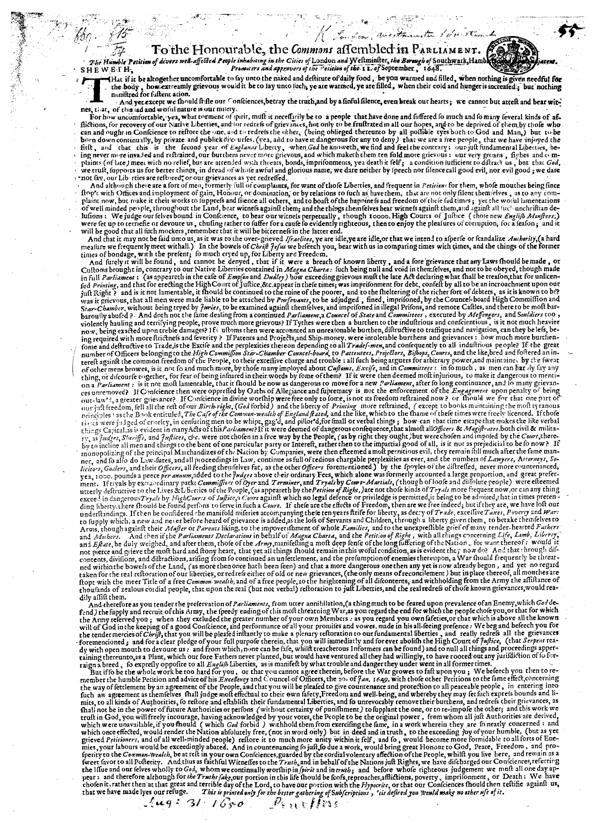

- [CORRECTED - 09.11.2017 - 2 illegibles] T.221 (7.5) Anon., The Humble Petition of divers well-affected People (31 August, 1650).

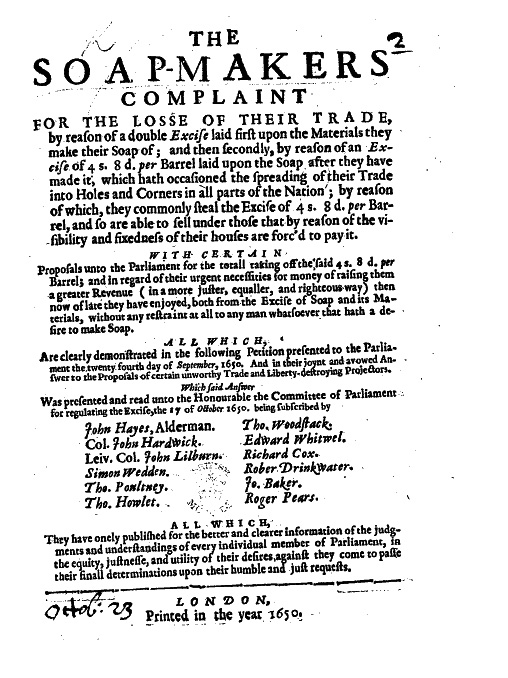

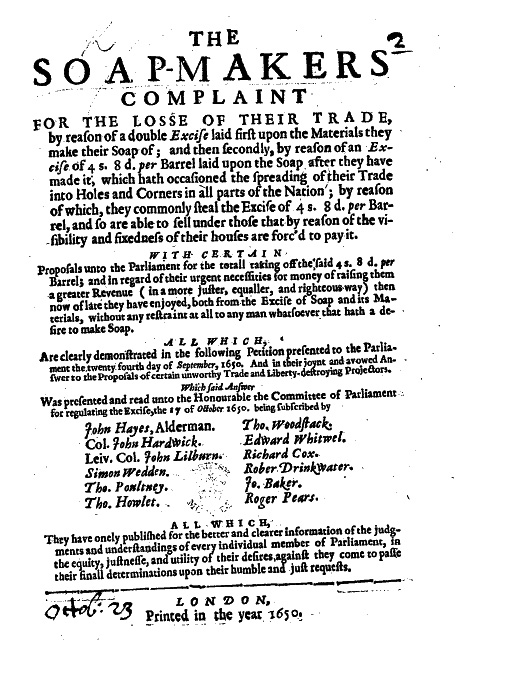

- [CORRECTED - 09.11.2017 - 1 illegible] T.222 (7.6) Anon., The Soap-makers Complaint for the losse of their Trade (24 September 1650).

- The Petition

- Answer

- Proposition to the Grand Commissioners of the Excise

- Answer Oct. 17, 1850

- Acount or Certificate of the Commissioners

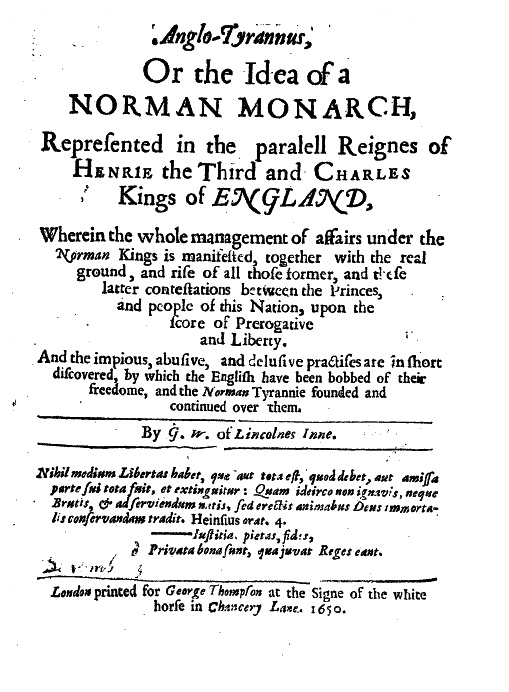

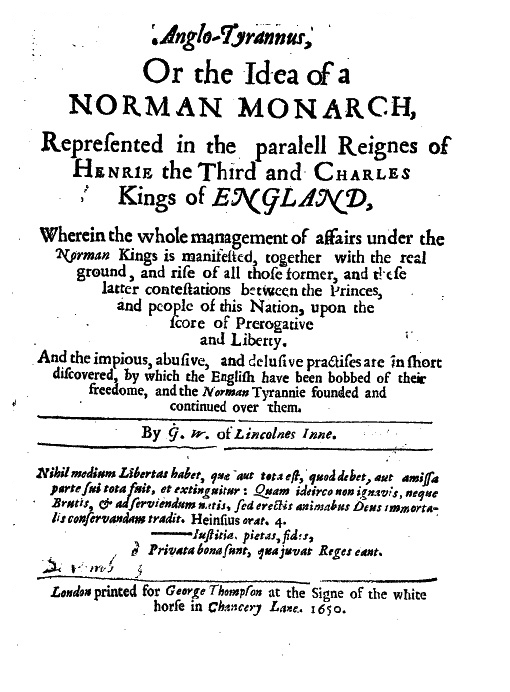

- [CORRECTED - 26.04.2018 - 131 illegibles] T.223 (7.7) George Walker, Anglo-Tyrannus, or the Idea of a Norman Monarch (3 December, 1650).

- [CORRECTED - 10.11.2017 - 5 illegibles] T.224 (7.9) William Walwyn, Juries justified (2 December, 1650/1651).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.274 John Milton, Defensio pro Populo Anglicano [First Defence] (1651). [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T. 303 [1651.??] Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common-wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill (1651). [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [CORRECTED - 12.07.16- 0 illegibles] T.225 (7.10) Anon., A Declaration of the Armie concerning Lieut. Collonel John Lilburn (14 February, 1651).

- The humble Petition of Officers and Souldiers, Citizens and Countrey-men, Poor and Rich; and all sorts

- The Freemans Appeal

- [CORRECTED - 10.11.2017 - 7 illegibles] T.226 (10.18) John Lilburne, A Letter written to Mr. John Price (31 March, 1651).

- [RE-CHECKED - 10.11.2017] T.293 [1651.05.15] (M14) Isaac Penington, The Right, Liberty and Safety of the People Briefly Asserted (15 May, 1651)

- [CORRECTED - 10.11.2017 - 0 illegibles] T.227 (7.18) Benjamin Worsley, Free Ports (1652).

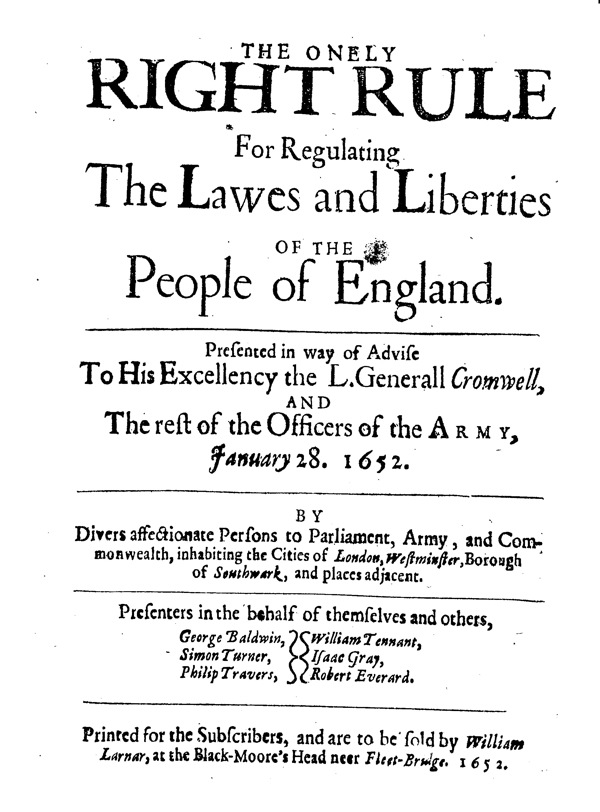

- [CORRECTED - 12.07.16 - 4 illegibles] T.228 (7.11) [Several Hands], The Onely Right Rule for Regulating the Lawes and Liberties of the People of England (28 January 1652).

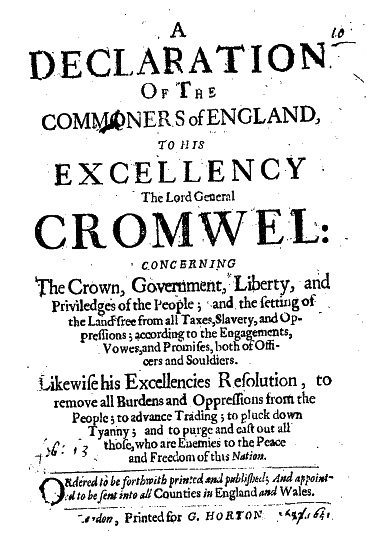

- [CORRECTED - 10.11.2017 - 1 illegible] T.229 (7.12) Anon., A Declaration of the Commoners of England (13 February, 1652).

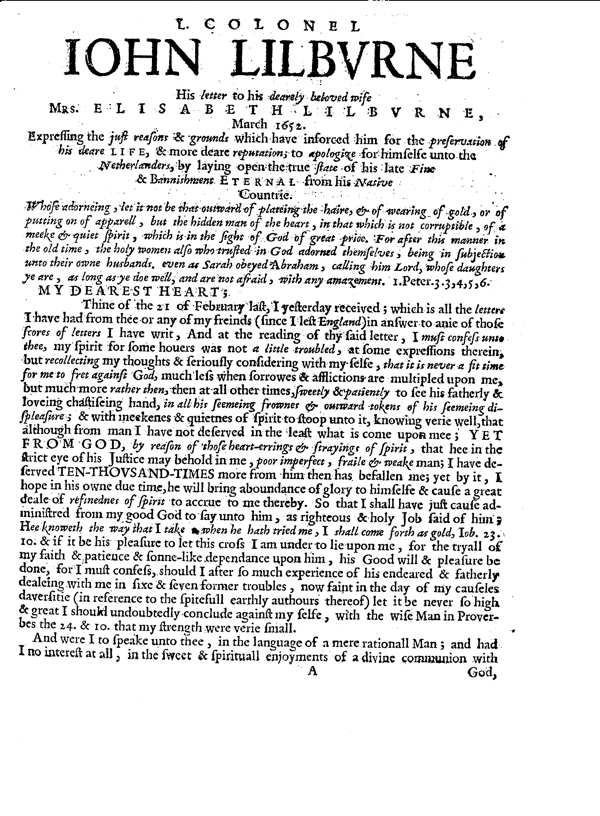

- [CORRECTED - 10.11.2017 - 0 illegibles] T.230 (7.13) John Lilburne, His letter to his dearly beloved wife (March 1652).

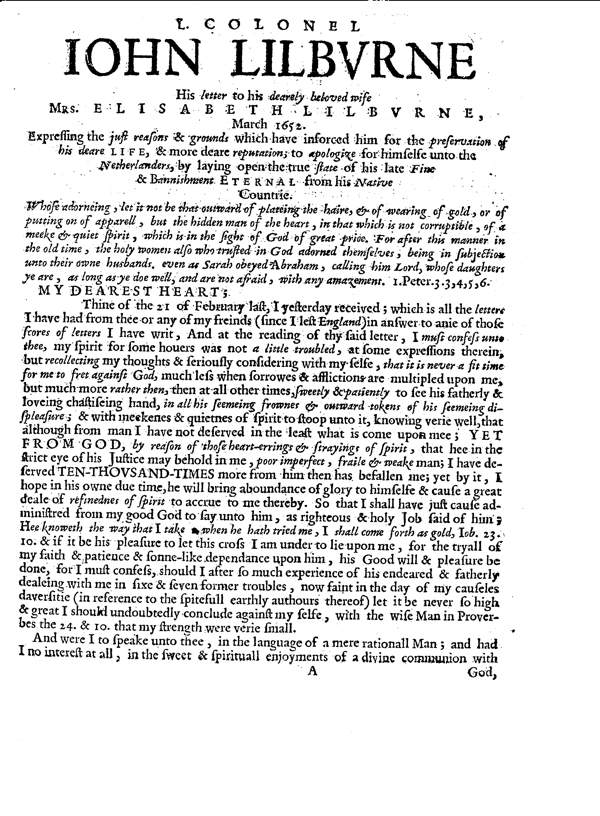

- [UNCORRECTED - 115 illegibles] T.231 (10.19) John Lilburne, His Apologeticall Narration (April, 1652).

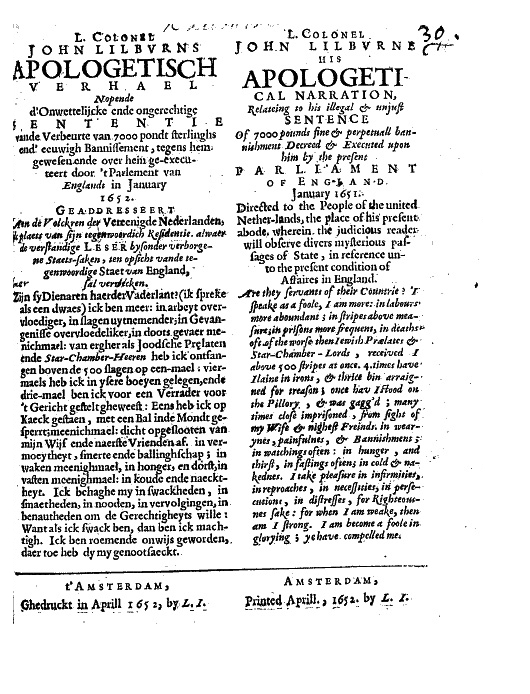

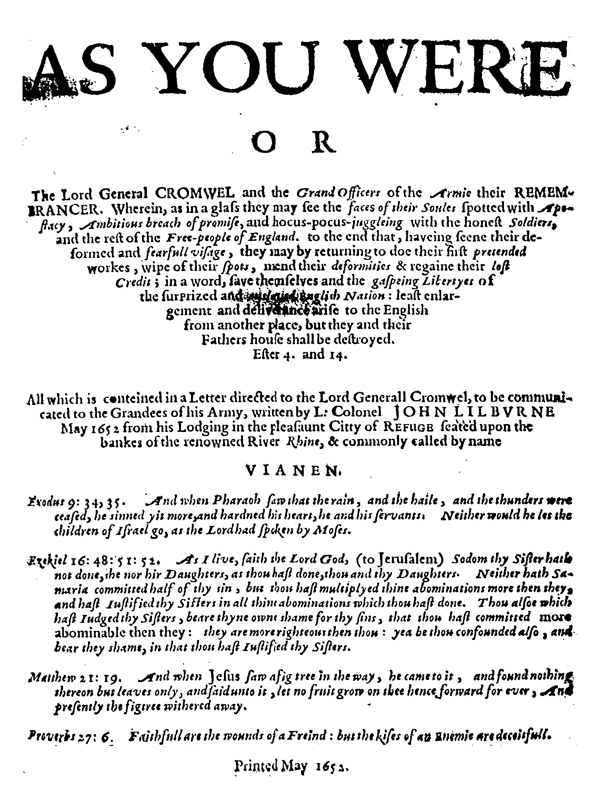

- [CORRECTED - 16.11.2017 - 5 illegibles] T.232 (7.14) John Lilburne, As you Were (May 1652).

- [CORRECTED - 07.06.2016 - 0 illegibles] T.233 (7.15) William Walwyn, Walwyns Conceptions; for a Free Trade (May 1652).

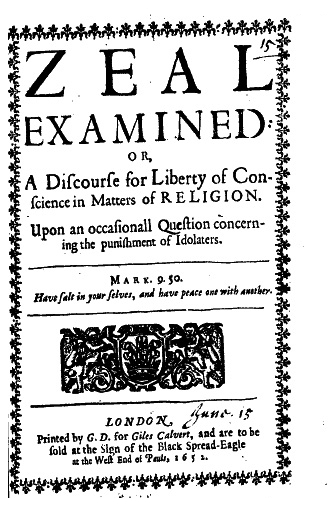

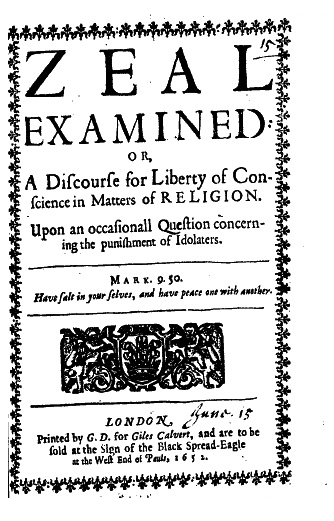

- [CORRECTED - 30.11.2017 - 15 illegibles] T.234 (7.16) Anon., Zeal Examined (15 June, 1652).

- Author’s Introduction

- Whether the Magistrate professing Christianitie, ought to punish Idolaters, according to the Law of Moses, or otherwise.

- An additionall Discourse, more particularly directed against the inmost Spirit of persecution, and against some fleshly and legall Principles relating thereunto, with a Word to the Magistrate.

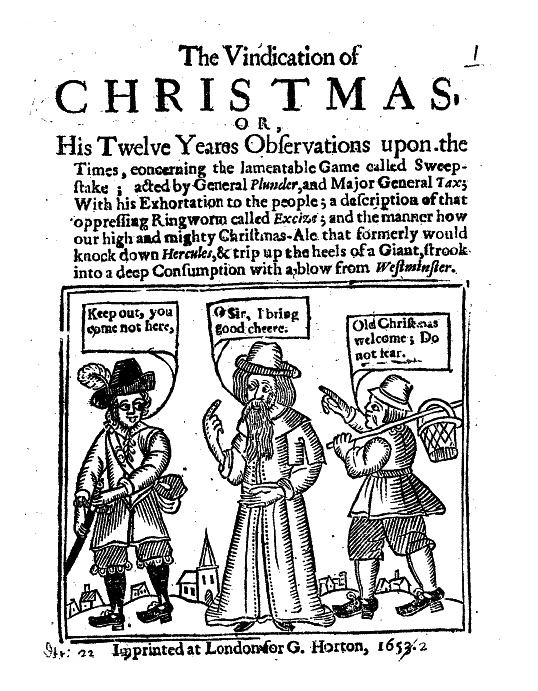

- [CORRECTED - 20.12.2017 - 16 illegibles] T.235 (7.17) Anon., The Vindication of Christmas (22 December, 1652).

- [CORRECTED - 20.12.2017 - 2 illegibles] T.236 (7.19) John Streater, A Glympse of that Jewel Libertie (31 March, 1653).

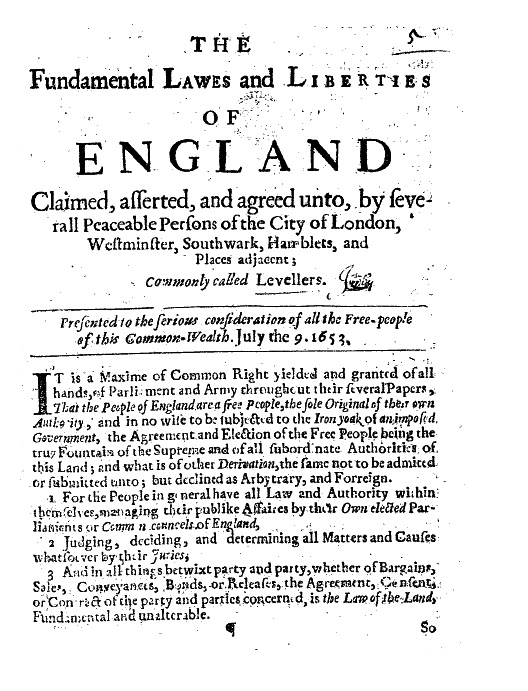

- [CORRECTED - 12.07.2016 - 1 illegible] T.237 (7.20) Anon., The Fundamental Lawes and Liberties of England (9 July, 1653).

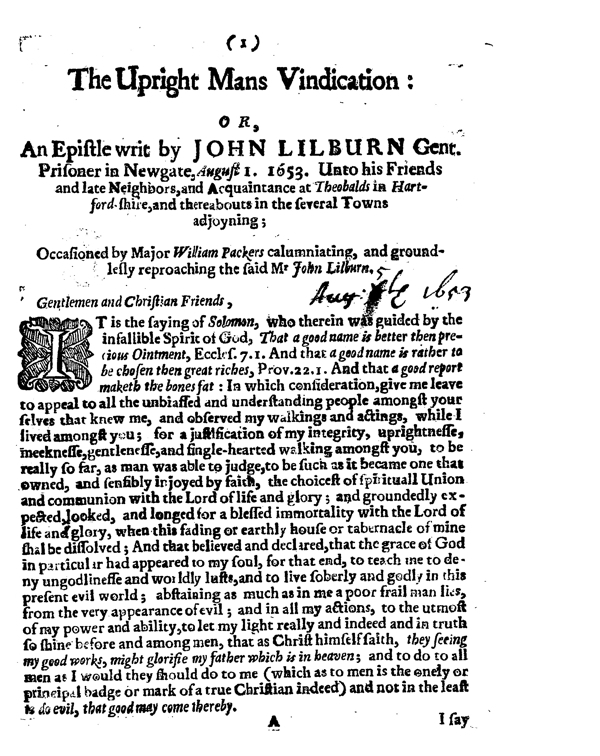

- [CORRECTED - 02.01.2018 - 12 illegibles] T.238 (7.21) John Lilburne, The Upright Mans Vindication (1 August 1653).

- Address from Calis, 14 June 1653

- Statement from his trial held on 13-16 July 1652

- Letter to General Cromwell from Dunkirk, 2 June 1653

- A List of petitions made on his Behalf by others

- Postscript, 1 August 1653

- Lilburne’s Answers

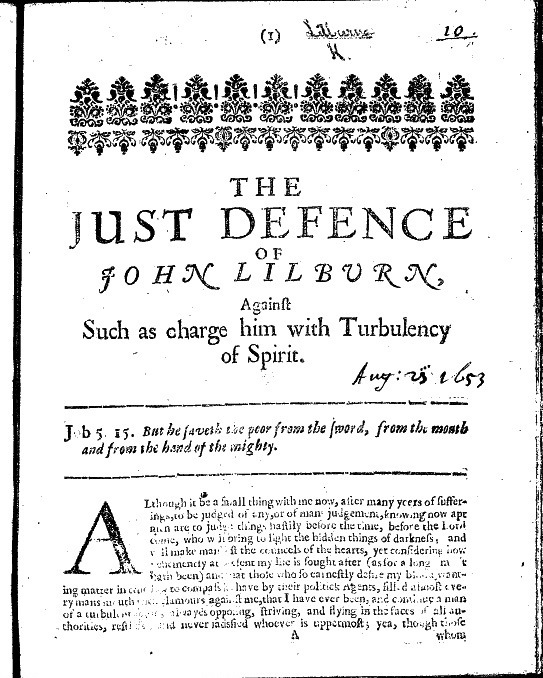

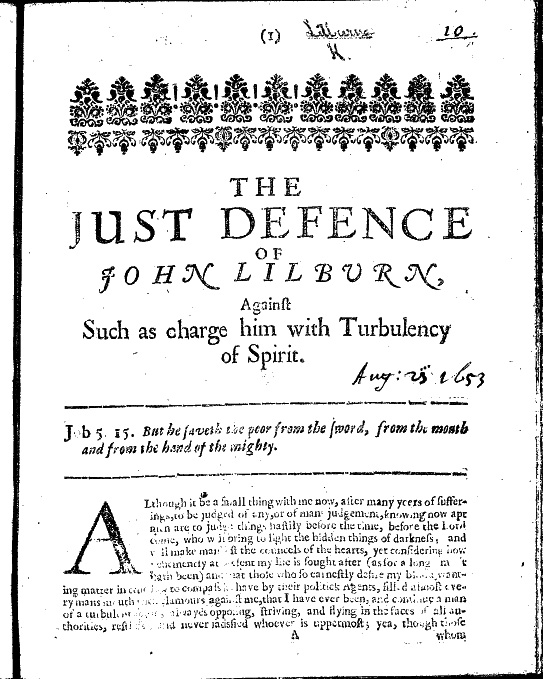

- [CORRECTED - 07.06.2016 - 30 illegibles] T.239 (7.22) John Lilburne, The Just Defence of John Lilburn (25 August 1653).

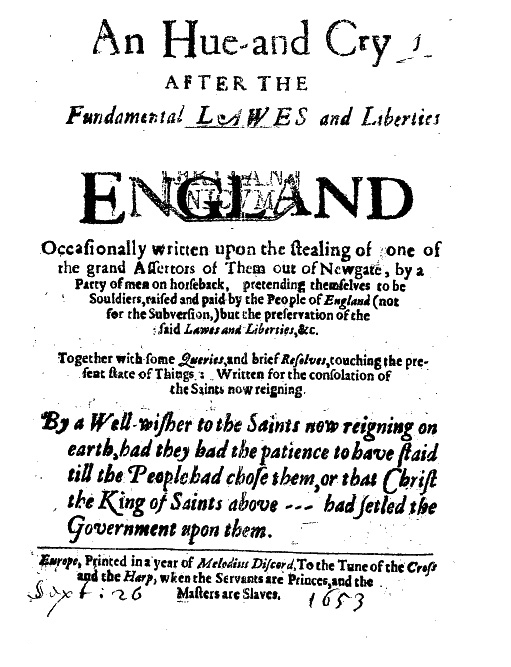

- [CORRECTED - 03.01.2018 - 57 illegibles] T.240 (7.23) John Lilburne, An Hue-and Cry after the Fundamental Lawes and Liberties of England (26 September, 1653).

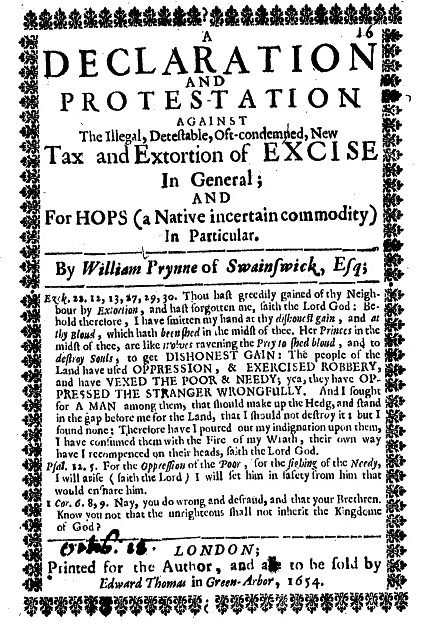

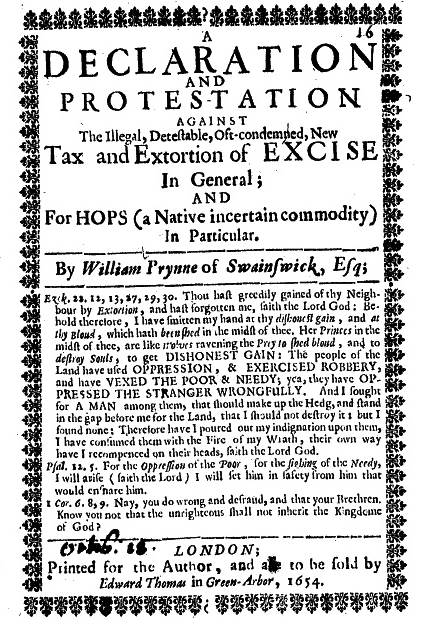

- [CORRECTED - 03.01.2018 - 24 illegibles] T.241 (7.24) William Prynne, A Declaration and Protestation against New Taxes (18 October, 1653).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.275 John Milton, Defensio Secunda [Second Defence] (1654). [elsewhere in the OLL]

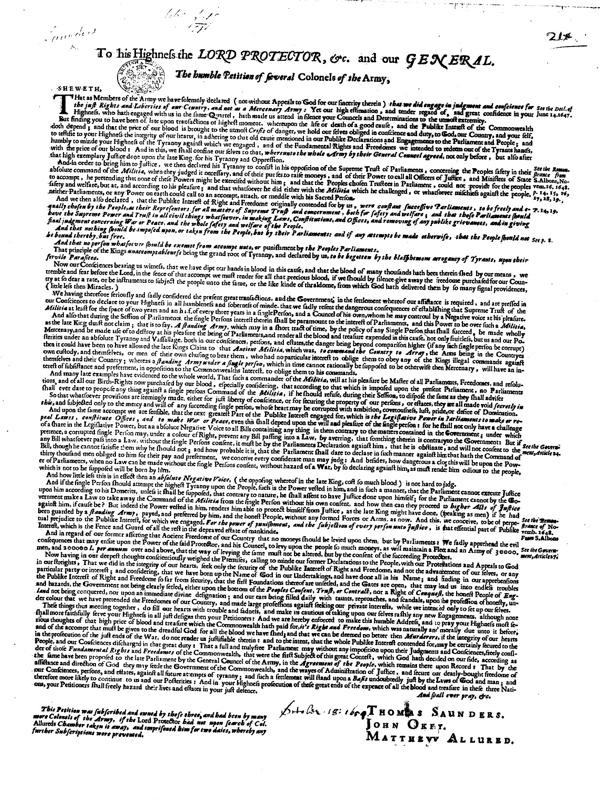

- [CORRECTED - 12.07.16 - 0 illegibles] T.242 (7.25) Thomas Saunders, The Humble Petition of Several Colonels (18 October, 1654).

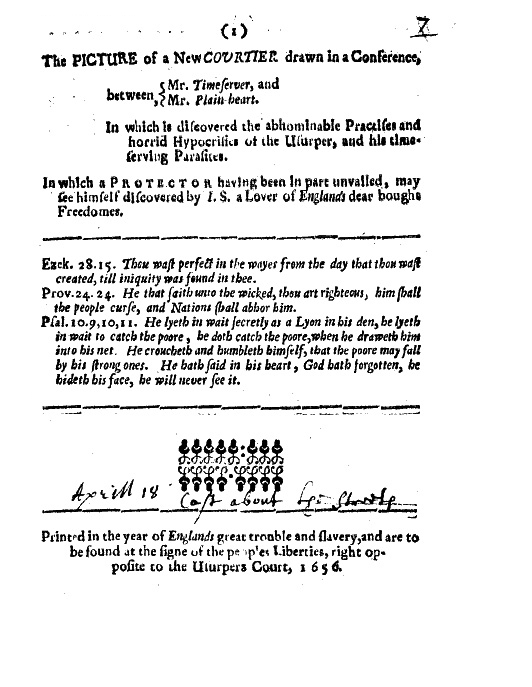

- [CORRECTED - 02.02.2018 - 21 illegibles] T.243 (7.26. John Streater, The Picture of the New Courtier (18 April, 1656).

- [CORRECTED - 02.02.2018 - 14 illegibles] T.244 (7.27) John Lilburne, The Resurrection of John Lilburne (16 May 1656).

- Letter to his wife Elizabeth Lilburne, 4 Oct. 1655

- Letter to William harding, 5 Oct. 1655

- Main body of pamphlet

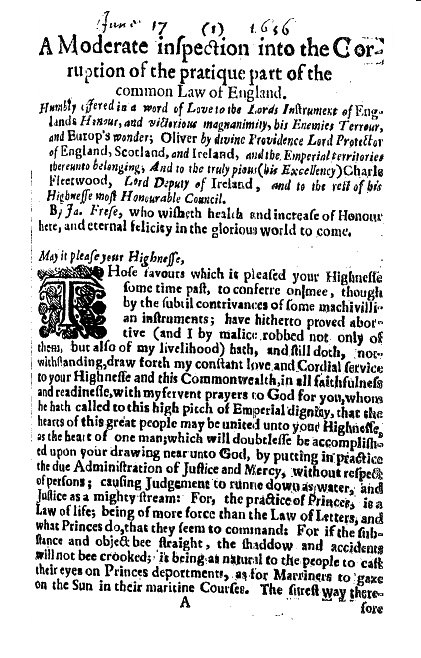

- [CORRECTED - 02.02.2018 - 13 illegibles] T.245 (7.28) James Freize (Freese), A Moderate Inspection into the Corruption of the Common Law of England (17 June, 1656).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.294 [1656.06] Marchamont Nedham, The Excellencie of a Free State: Or, The Right Constitution of a Commonwealth (summer 1656) [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.295 [1656.09] James Harrington, The Commonwealth of Oceana (July-Sept. 1656) [elsewhere in the OLL]

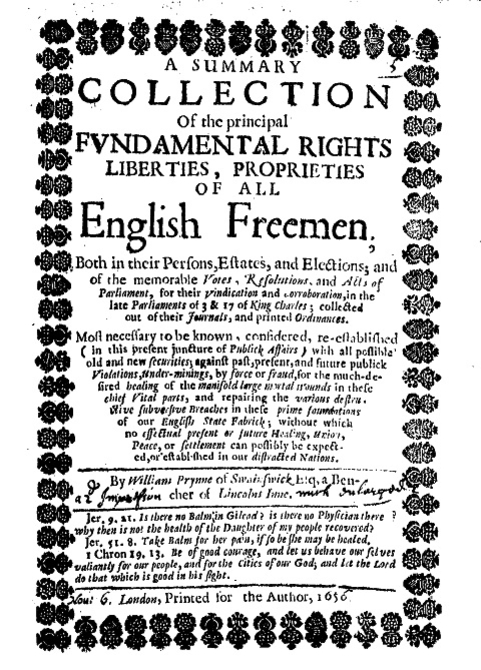

- [CORRECTED - 19.04.2018 - 14 illegibles] T.246 (7.29) William Prynne, A Summary Collection of the principal Fundamental Rights, Liberties, Proprieties of all English Freemen (6 November, 1656).

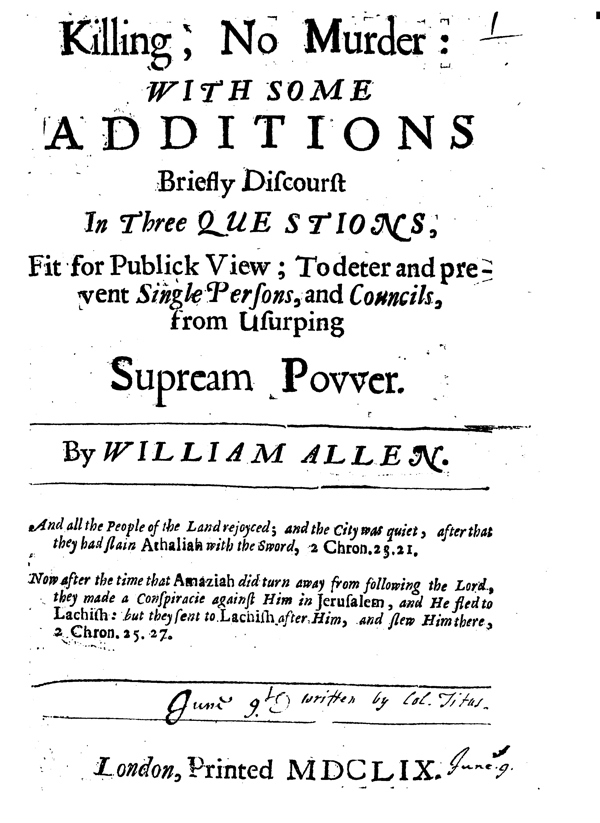

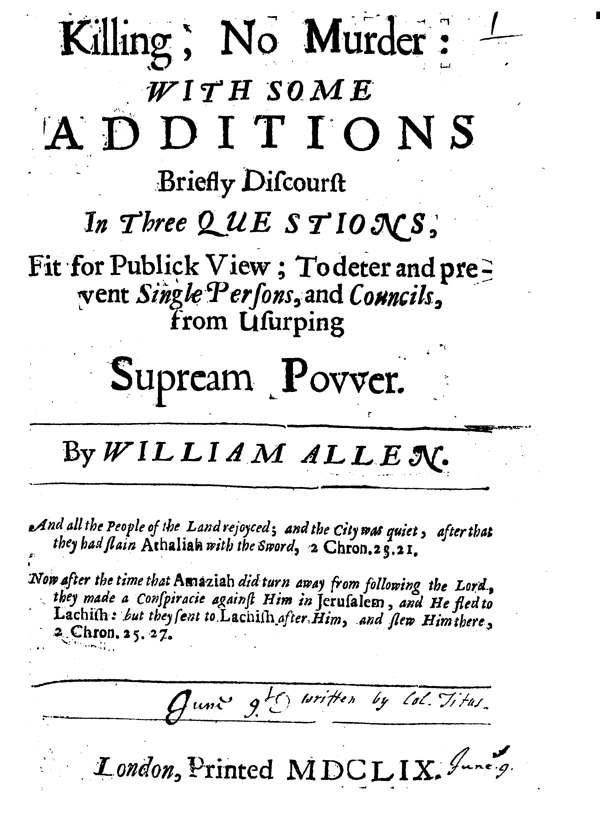

- [CORRECTED - 15.03.2018 - 74 illegibles] T.247 (7.30) Edward Sexby, Killing, No Murder (21 September, 1657).

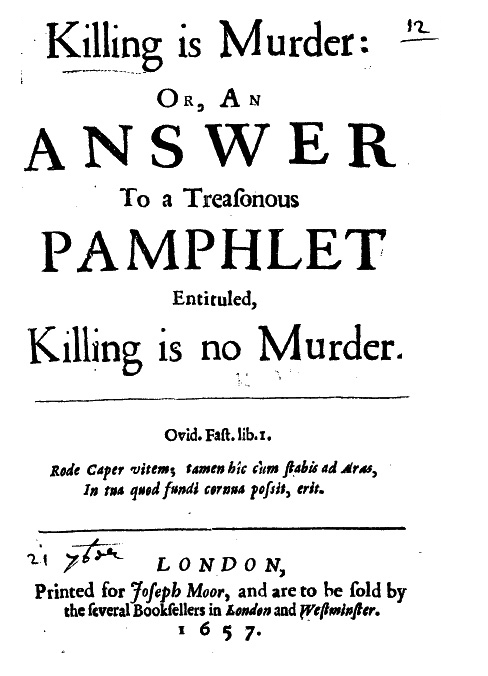

- [CORRECTED - 11.05.2018 - 74 illegibles] T.248 (7.31) Anon., Killing is Murder (21 September, 1657).

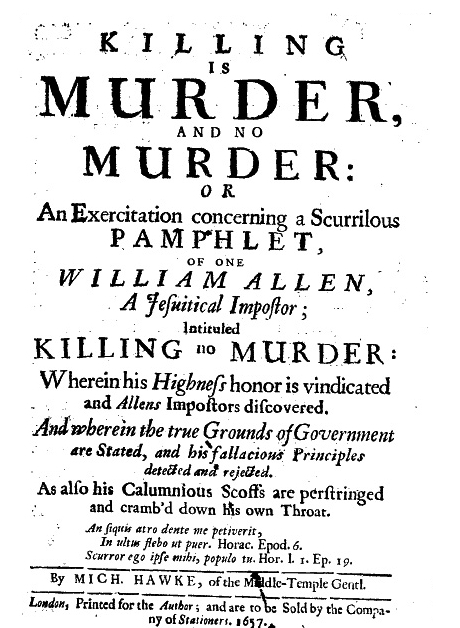

- [CORRECTED - 18.05.2018 - 92 illegibles] T.249 (7.32) Michael Hawke, Killing is Murder (1657).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.296 [1658.??] James Harrington, The Prerogative of Popular Government (1658) [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.299 (1659.??) James Harrington, Political Aphorisms (1659) [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.276 John Milton, A Treatise of Civil Power in Ecclesiastical Causes (Feb., 1659). [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [CORRECTED - 12.07.16 - 1 illegible] T.250 (7.33) Anon., The Leveller: Or The Principles & Maxims Concerning Government and Religion (16 February 1659).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.297 [1659.02.19] James Harrington, The Art of Lawgiving (20 Feb. 1659) [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [CORRECTED - 17.04.18 - 0 illegibles] T.251 (7.34) William Allen, A Faithful Memorial of that Remarkable Meeting (27 April 1659).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.277 John Milton, Considerations Touching the Likeliest Means to Remove Hirelings out of the Church (May, 1659). [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [CORRECTED - 18.04.18 - 34 illegibles] T.252 (7.35) James Freize, The Out-cry! (16 May, 1659).

- [CORRECTED - 26.04.18 - 5 illegibles] T.253 (7.36) John Streater, Government Described (1 June, 1659).

- [CORRECTED - 26.04.18 - 2 illegibles] T.254 (7.37) Anon., Lilburnes Ghost (22 June, 1659).

- [CORRECTED - 26.04.18 - 6 illegibles] T.255 (7.38) Zachary Crofton, Excise Anotomiz’d, and Trade Epitomiz’d (20 September, 1659).

- [CORRECTED - 14.05.18 - 0 illegibles] [Move to vol. 6 - 1649??] T.256 (7.39) William Bray, A Plea for the Peoples Good Old Cause (2nd ed., 17 October, 1659; 1st ed. 24 Oct., 1649).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.278 John Milton, A Letter to a Friend (Concerning the Ruptures of the Commonwealth) (20 Oct., 1659). [elsewhere in the OLL]

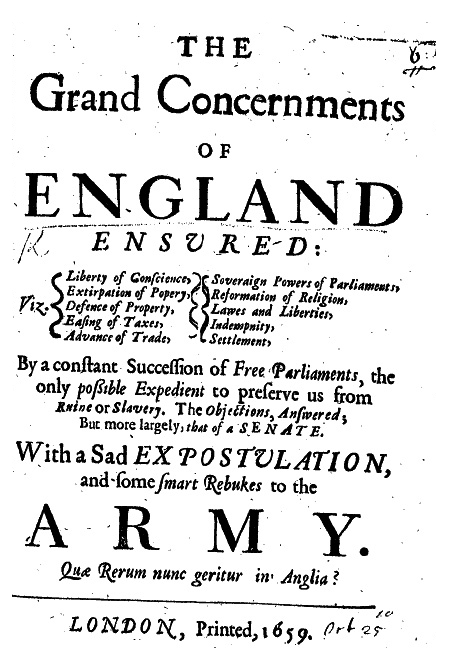

- [CORRECTED - 23.05.18 - 132 illegibles] T.257 (7.40) Anon., The Grand Concernments of England ensured (25 October, 1659).

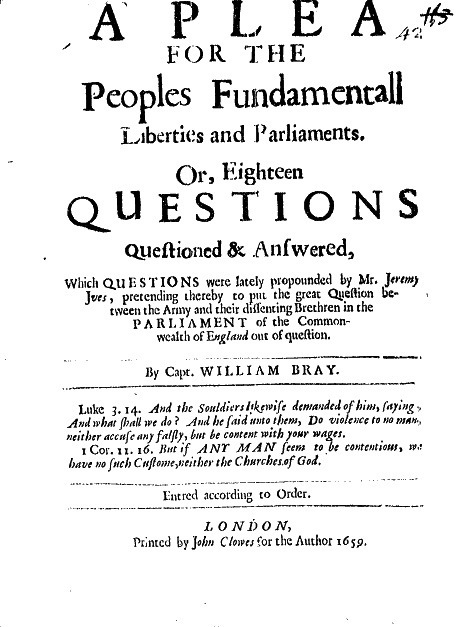

- [CORRECTED - 16.05.18 - 1 illegible] T.258 (7.41) William Bray, A Plea for the Peoples Fundamentall Liberties and Parliaments (1660).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.279 John Milton, The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth (March, 1660). [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.280 John Milton, A Letter to Monk (The Present Means and Brief Delineation of a Free Commonwealth) (?? Mar., 1660). [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.281 John Milton, Brief Notes Upon a Late Sermon (titled The Fear of God and the King) (April, 1660). [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.298 [1660.??] James Harrington, A System of Politics (1660-62) [elsewhere in the OLL]

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T. 304 [1662.??] Thomas Hobbes, Behemoth: The History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England (1662). [elsewhere in the OLL]

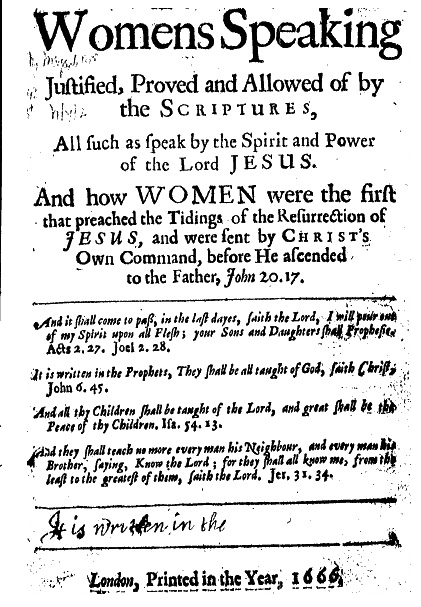

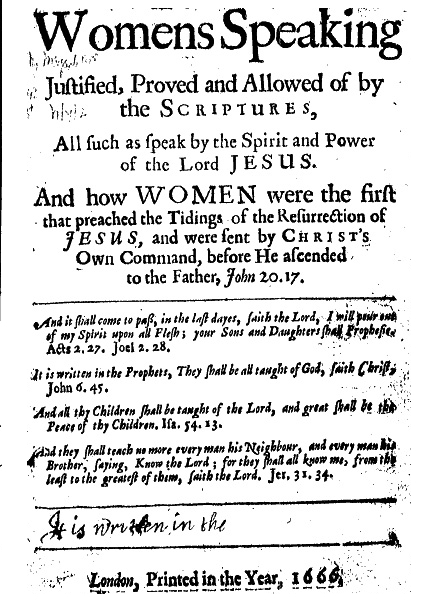

- [CORRECTED - 08.01.16 - 14 illegibles] T.259 (7.42) Margaret Fell Fox, Womens Speaking Justified (1666).

- Womens Speaking Justified

- A further Addition in Answer to the Objection

Introductory Matter↩

[Insert here]:

- intro image and quote

- Publishing History

- Introduction to the Series

- Publishing and Biographical Infromation

- Key to the Naming and Numbering of the Tracts

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

- Further Reading and info

Key (revised 21 April 2016)↩

T.78 [1646.10.12] (3.18) Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646).

Tract number; sorting ID number based on date of publication or acquisition by Thomason; volume number and location in 1st edition; author; abbreviated title; approximate date of publication according to Thomason.

- T = The unique “Tract number” in our collection.

- When the month of publication is not known it is indicated thus, 1638.??, and the item is placed at the top of the list for that year.

- If the author is not known but authorship is commonly attributed by scholars, it is indicated thus, [Lilburne].

- Some tracts are well known and are sometimes referred to by another name, such as [“The Petition of March”].

- For jointly written documents the authoriship is attributed to "Several Hands".

- Anon. means anonymous

- some tracts are made up of several separate parts which are indicated as sub-headings in the ToC

- The dating of some Tracts is uncertain because the Old Calendar (O.S.) was still in use.

- (1.6) - this indicates that the tract was the sixth tract in the original vol. 1 of the collection.

- Tracts which have not yet been corrected are indicated [UNCORRECTED] and the illegible words are marked as &illegible;. Some tracts have hundreds of illegible words and characters.

- As they are corrected against the facsimile version we indicate it with the date [CORRECTED - 03.03.16]. Where the text cannot be deciphered it is marked [Editor: illegible word].

- After the corrections have been made to the XML we wil put the corrected version online in the main OLL collection (the “Titles” section).

- [elsewhere in OLL] the document can be found in another book elsewhere on the OLL website.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement↩

The texts are in the public domain.

This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Editorial Matter↩

[Insert here]:

- Editor’s Introduction to this volume

- Chronology of Key Events (common to all volumes)

Tracts from 1650-60 (Volume 7)

[move to vol. 6??] T.216 (7.1) Richard Hollingworth, An Exercitation concerning Usurped Powers (18 December, 1649/1650).↩

Editing History

- 1st edition uncorrected: added 27 June, 2015

- Date corrections completed: 9 May 2018

Bibliographical Information

ID NumberT.216 [1649.12.18] (7.1) Richard Hollingworth,, An Exercitation concerning Usurped Powers (18 December, 1649/1650).

Full titleRichard Hollingworth,, An Exercitation concerning Usurped Powers: wherein the Difference betwixt Civill Authority and Usurpation is stated. That the Obedience due to lawfull Magistrates, is not owing, or payable, to Usurped Powers, is maintained. The Obligation of Oaths, and other Sanctions to the former, notwithstanding the Antipolitie of the latter is Asserted. And the arguments urged on the contrary part in divers late printed discourses are answered. Being modestly, and inoffensively managed: by one studious of Truth and Peace both in Church and State.

Tyrannus sine titulo ille est qui imperium ad se, absque legitimâ ratione rapit, huic quisque privatus resistat, & sipossit e medio tollat. Vide sacram Theolog. per Dudleium Fennerum. cap. 13. de polit. civili. pag. 80.

Si Invasor imperium arripuerit, neque paction ulla sequuta sit, aut fides illi data, sed sola vi retineatur possessio, à quolibet privato jure potest interfici Grotius de jure pacis ac belli, p. 86.

Luke 21.8. But when ye shall hear of Warres, and commotions (or seditions) be not terrified.

London, Printed in the yeer, 1650.

Estimated date of publication18 December, 1649/1650. [Thomason records the date he collected this pamphlet as "18 December, 1649 but the pamphlet is dated "1650" on the front page.]

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 779; Thomason E.585 [2]

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.) Many of the margin notes contained Latin text which was undreadable. We have done our best to decipher them.

Text of Pamphlet

The Contents of the First Part.

- CHAP. I. Of Vsurpation, what it is. A Case propounded, wherein it is not hard to determine whether Vsurpation be chargeable, or not.

- CHAP. II. Of yeelding Obedince to a Power usurped as above said. That it is not lawfull to give up ones self to the Allegiance of such a Power.

- CHAP. III. This Question discussed. Whether submission to, and acting under a usurped Power, for the time, be lawfull, with a reservation of allegiance to the lawfull Power, supposed to be expulsed.

- CHAP. IV. The obligatorinesse of the Oaths and Covenant, urged in the second Chapter against Obedience to Vsurpers, made good against divers late Authors.

- CHAP. V. The Reasons brought for obedience to Vsurpers, and acting under them, Answered.

To the Reader.

Christian Reader,

If thou knewest the Gentleman the Authour of this Tract, thou wouldest reade it for his sake. And if thou once reade it through without prejudice, thou wilt respect it for its own sake.

His eminent fidelity to the Parliament, according to their first declared principles, is evidenced, as heretofore by severall appearings and sufferings in their behalf, so now by this Tract. It is weighty for the matter, and wisely handled for the manner and method of it. A strain of Religion, and strength of Reason running all along through it. His weapons are spirituall, the Word of God and right reason, not carnall policy or power, weapons now most in use.

He judgeth of actions (as wise men doe) by themselves, not by their successes: he accounts not prosperous vice a vertue, nor prevalent resistance of lawfull Magistracy lesse sinfull, then if it had not been prevalent, nor the Mahumetan party to be any whit the more blessed or beloved of God, because by force or fraud (through Gods permission) they at first raised, and have for sundry centuries of years continued to themselves a large Empire by the ruine of many millions of Christian Souls: knowing that the prosperity of fools (that is of Hypocrites and wicked men) shall at last destroy them. Prov 1. 32.

By that wisdome which is from above, which is first pure then peaceable, he rightly seeks after Peace, by clearing up Truth, promoting righteousnesse: proportioning to each their own due, and placing them in their own rank and station, Truth, order, rightteousnesse are foundations and pillars, if not parts of true Peace; without these either there is no peace (as if the servants of this City being more & stronger, then their Masters should slay or banish them, & quietly divide amongst themselves their Lands and Goods, were this a Peace?) or if it may be called a peace, it is but a base brutish, [Editor: illegible word] practise, and destroy the mightle and holy people. Dan. 23, 24, 25.

This Authors zeal for the obligation of solemne Oaths, Vows, and Covenants may well be born with; if it be a fault, there is but little (too little) of it in England. But the good man though he sweareth to his own hurt, changeth not. Psal. 15. 4.

I will say no more, but Tolle lege, take up and read, understand what thou readest; Remember and practise what thou understandest to be the will and minde of God, and pray for such (whether of the Gentry, Ministery, or others) as long, and labour for thy Information, and reformation, if them wandrest; and for thy confirmation, and consolation if thou walkest aright. The God of truth and peace be with thee. Amen.

Of Vsurpation, what it is; a Case propounded, wherein it is not hard to determine whether Vsurpation be chargeable, or not.

USurpation is an intrusion into the Seat of Authority, a presuming to possesse, and manage the place & power thereof without a lawfull calling, right, or title thereunto. A lawfull call or title to that rule, and Government which is supreme (of which I have to speak) is derived, or comes from God, There is no power but of God, (saith the Apostle) the powers that be are ordained of God: Rom. 13. 1. It were a sense too large, and not to be defended to take these words absolutely, and unlimitedly of all power, in regard either of title, or measure, and use. An unjust power in regard of Measure, or the stretching of Power beyond its due bounds, or the abuse of it is generally denyed to be of God by way of warrant; and an unjust power in regard of title, or an Authority set up, and admitted against, or without right, God himself denyes to be of him. They have set up Kings, but not by me; they have made Princes, and I knew it not: saith he, Hosea 8.4. Which speech is by the current ofa Expositors applyed to Jeroboam, and his successors, coming in to be Kings of Israel in that manner as they did; For although Jeroboam had a prediction (yea, suppose it a grant) that he should be King of ten Tribes, 1 King. 11. 29. yet the people, at Solomons death, had no command, or direction from God to cast off Rehoboams government, and make him their King; it was therefore sedition, and rebellion in them; and both a manifest breach of the fifth Commandment;Vide Paræum in Hos. 8. 4. and of the positive Law of God, Dent. 17. 14, 15. and Jeroboam was faulty in that, though he had Gods preconcession of a Kingdom over ten Tribes; yet having had no order from him about the time, manner, or the particular ten which they should be; he did not seek and tarry for a further direction, and calling from God; as David did in the like caseb. And although the Lord, when it was done, testified that the thing was from himc; yet we must understand it to have been so by his permissive counsell, and generall concourse, or providence onely, as all actions as they are actions, and all events that are evils of punishment; and as they are such, are, though the actors among men that bring them be never so sinfull in them; but not by his approbation, appointment, or constitution; the event was from God; but not the sinfull means by which it was accomplished; he ordered the evil carriage of men to that effect, but he gave them no order for that evil carriage: so that though, in a sense, it was of him; yet in regard of authorizing, it was without, and against him, and, in the Apostles sense, none of Gods ordinance. But of this we shall have occasion to speak again hereafter.

God giveth a calling, or invests with a right to Soveraignty, either immediately, by making and declaring the choice, and designing the person himself; or mediately, by committing it to the people to elect, and constitute both their form of Government, and the persons that are to sway it over them, which he hath done to all Nations; yet with a reservation to himself of power to interpose with his own immediate designation when he pleaseth: and when he doth not so, the vote of the people is the voice of God, (ordinarily) and they passing their consent when a Magistrate is to be set over them, that power, so constituted, is of God, as his ordinance. And this may be the reason why that, which in one place is called the ordinance of God, is, in another called the ordinance of man, or an humane creature: 1 Pet. 2. 13. By the former way the Judges and Kings of Israel had, or ought to have had their admission to rule,d and that was extraordinary, and peculiar to that people; the latter is the onely ordinary, lawfull, and warrantable way of creating a right, and title to the helme of Magistracy in other Nations. And as in the former the call of God was sometimes personall, or of one single person; as was that of Moses, Joshus, Samuel, Saul, and others: and again, sometimes lineall, or of a whole race: as was that of David and his seede: So it is in the latter,f the peoples constitution of their Governors may either be individuall, or intransient; as in those kingdoms, or States which are called (in a strict acception) Elective; or it may be continuated, and successive; as in those Kingdoms, or Principalities which are called hereditary, and possessed by descent: both wayes Princes are by the peoples Election, and Consent; and the latter is preferred, by many wise Statists, before the formerg.

I shall not insist on the distinctions, that might be observed touching the manner of the peoples passing their consent; nor determine which of them is sufficient, and which not, to make this right or title, whether it must be antecedent to possession, or may be consequent, expresse, or tacite: collective, or representative: absolute, or conditionated: free, or enforced: revocable, or irrevocable. The consideration of these is not materiall to the resolution of what is in question; it sufficeth that it be yeelded, that the peoples consent is (besides that which is by commission immediately sent and signed from heaven) the onely derivation of a lawfull call, or claim to Governmenth. When our Saviour Christ (who being such an extraordinary person, might have warrant to do what would have been presumption in any other) was appealed to in a cause that appertained to the civill Magistrates decision; he refused to deal in it, with these words, Who made me a Judge, or a divider over you? according to which words of him, who was the truth, he that may rule, must be placed in that office by some body, and may not undertake it of himself: no man may take this honour to himself, or be his own advancer to the Throne; but he must be installed by another: and what other creature, besides the Nation it self, can challenge a power to appoint over it its Rulers is not to me imaginable. Angels are not of this Oeconomie, do not intermeddle in this businesse, and for other people, or forrein States they are but in an equalitie, and have no partnership in this matter; they have no more to do to impose Governors over their neighbours, then they have reciprocally over them; and to whichsoever may attempt it towards the other, by the analogy of our Saviours words, it may be said,Luk. 12. 13, 14. Who made thee a Judge, or Rule-maker over me?

A calling from the people, who are to be subject being so necessary, and essentiall to a humanely constituted Magistracie; it is easie to discern what is Usurpation, viz: that which is opposite to it, or privative thereof, which is a snatching hold of the Scepter, and wresting it out of the hands of those who are to dispose of it, or have it committed to them: it is ordinarily termed, a tyrannie in regard of title, or without title: The distinction betwixt lawfull Magistrates and Tyrants is thus given by Aristotle:h Kings do reign, not onely according to the Law, but over them that consent to them; Tyrants rule over men against their wils.Etenim si nolentibus imperatut, regnum protinus esse definit. Tyrannis efficirur quæ vi dominatur. If any govern against the minde of the governed, it ceaseth to be a Kingdom, and becometh a Tyrannie which ruleth by force. All lawfull power then is founded upon the wils of those over whom it is set; Contrariwise Usurpation is built upon the will and power of them that hold the Government; it is a self-created, or self authorised Power, such was that ofi Cinna, and Carbo, who made themselves Consuls, without any Court-election, in the time of the Romane sociall war betwixt Sylla and Marius and that ofk Julius Cæsar who made himself Consul, together with Publius Servilius; such was that of the Chaldeans over the Jews, Hab. 1. 7. Their judgement and their dignity shall proceed of themselves, saith the Prophet, that is, as Deodate expounds it, they received no Law,Verum regnum est imperium voluntate civium delatum: at si quis vel fraude, vel violentia dominatur manileste Tyrannis est. idem. li. 5. num. 112. nor assistance from any; their right consists in their will, and the execution in their power.

Usurpation being defined, we may proceed to distinguish of it according to severall heights, or degrees it is capable of; as 1. It is either where the Throne is vacant, and undisposed of (which may happen sundry wayes, as when a Common-wealth is new erected, or the possessors of the Government resigne, or are extinct, and none left to lay claim to it) or, where it is full, and possessed de jure, and the Rulers are onely violently extruded, and kept out.

2. Usurpation is either meerly in point of Title, and administration of a received and settled Government; or by way of innovating in the Government it self; over-turning the constitution of it, and forming it a new.

3. It may come to be acted either from those without, viz: Forreiners, and strangers to the State; or by Natives, and naturall Subjects of the Kingdome.

4. It is done by these, either against the single tye and duty of obedience and Allegiance owed to the present lawfull Authority; or against Allegiance bound with Oaths and sacred Covenants. All the sorts of each of these distinctions are direct, and formall usurpations, but the latter of each far surpasseth the other respectively, and a conspiration of them all makes an Usurpation of a meridian altitude; when a party owing obedience and subjection to a long continued, and undoubted lawfull power, and solemnly sworn to submit too, and support that Government, shall rise up, and presume to thrust out the possessors, and invest it self, yea, and not onely seize on the Power; but of its own minde, and will, or, by its force alone, abolish the settled, and set up a new mould of government; this is Usurpation to the culmen or height of it.

Having thus found out what Usurpation, and what the Zenith of it is; we may put a case wherein it will be easie to give a Judgement cleerly. Suppose a Nation in America, whose fundamentall government is, and hath been anciently and confessedly constituted, and placed in a King, an House of Peers, and an House of Commons sitting in a collaterall, or coordinate rank, in regard of supremacy of power; the King being the supreme in order (unto whom, in such an association, Oaths of Allegiance and supremacy are generally sworn) next to him the Peers as the Upper, and the Commons as the Lower House of Parliament. Suppose also, the King, according to his place, summoning them, and they conformably assembling together in Parliament, and he and they personally concurring to act in the highest affairs of government; in the processe whereof differences arise betwixt the King, and the said two Houses; which grow to that height, as that he in person departs from them, a war breaks out betwixt them; the Kingdom is divided by partieship with them, on the one side or the other; the two Houses continue acting joyntly, no: onely in managing their military defence; but in the other publick, both religious and civill affairs of the Kingdom; they petition, remonstrate, and declare for a necessitie of an association, and conjunction of the King and the two Houses as the fundamentall constitution, and government of the Kingdome; they enter into, and prescribe to the people Protestations, Vows, Oaths, and Covenants, for the upholding of the Authority and Power of both so constituted: they professedly fight for that associated Power, they proclaim them Enemies and Traitors, they prosecute them with fire and sword, sequestration of estates, and other punishments, that go about to divide them asunder, or oppose the aforesaid Authority; and all this they do, and avow as the indispensably necessary discharge of their trust. Suppose after all this, the Army raised and imployed by the said two Houses in the aforesaid war, consederating in their Leaders (as by the immediate sequell manifestly appears) with a small party in the Lower House; Remonstrates to that House (without any addresse to the other) many high and strange things they would have done by them, and amongst the rest, that the King be proceeded against, as for treason, and other capitall crimes; in like manner his two eldest Sons, if they render not themselves within a day to be set them: that it be declared that the peoples Representatives in the House of Commons shall have the supreme Power, and all other shall be subject to them; in which demands, that House not being so obsequious to them as they expect, but standing upon the collegueship of that Government, which they with their associates, the King, and the House of Peers are intrusted with; the Army, forthwith, marcheth up to the doores, and by force of Arms seizeth on, and shuts up in hold one sort of them; and by a strong guard set at their doores shuts out another, suffering onely a small number of them, and such as please them to sit in the House. Suppose lastly, this little number, left in the House, shall approve of, and second these proceedings of this Army; and by their act, or Vote confirm the seclusion of that greater number of the Members of that House; and, taking upon them to Act in the name of that House, shall Enact or declare themselves to be the onely Supreame Authority in the Nation, and by that pretended solitarinesse, and supremacy of power shall take away, and abolish the other House of Parliament, destroy the life of the King, deny, and disanull the Title of his Heirs, and Successors, to the Crown and Kingdome; abollish the office of a King, and ordain and govern solitarily over the people, as their onely supreame Power, and require their obedience, and subjection as to such. The quare, in this case thus propounded is, whether this said party, as thus acting, and as to this latitude of Authority, be usurpers, yea, or no? whether this their removing others from the Seat of Supreame Power, and assuming it peculiarly to themselves, be, or be not Usurpation (as Usurpation hath been before prescribed) and that to the very apex, or highest pinacle of it; yea, whether they be, or be not guilty of a double Usurpation?

First, in usurping the name and Authority of that House. It may haply be said for this. 1. That possibly they may make a quorum, or as many in number as are required to act. R: But are they not supposed to be under actuall and present force, which hath been, without contradiction by any, adjudged a ground of nullity to Parliamentary proceedings. For though all are not required to be present, yet the House must be free for all to come to, that their acts may be free and authorative.

2ly, That perhaps they may be most willing, voluntary, and free in their acts, and the force that hath taken away others may be no force but a security to them, being of the same principles, apprehensions, and designes with them. R: But though they as men may be free, yet taking upon them the name of the House, are they free as an House? the House includeth virtually every Member of it, many whereof being violently excluded by those that guard the meeting place, how free soever those persons are that sit, how can the House be said to be free? nay, doth not their voluntarinesse and free complyance make the Usurpation compleater? Could they be said to be enforc’d to declare, and act such things, we might by a favourable interpretation, onely judge their Acts to be null; but when their proceedings flow from their own wils, and they so concur to the exclusion of others more then themselves from the exercise of the power they with them are intrusted with, and assume to themselves a power, never confirmed on them by the people, but meerly of their own creation, how can this be lesse then Usurpation to the life?

2ly, In usurping (in the name of that House) the sole supremacy of Power in the Nation. It will be pleaded: perhaps, that the House of Commons, in the supposed case, is the onely Representative of the people, to whom alone the Nation hath committed the Supreme Power. R: 1. That House is not a Representative of the whole Nation, but onely of the Commons, which though the bulk, and far more numerous part; yet cannot stand for the whole in choosing a Representative, but onely for themselves. 2. If it could be made good, that to that House, the whole Nation, in the originall constitution of Government, had committed the sole Power; the quare would easily be cast in the negative: but how will that be proved? The case, as it is put, presupposeth Antiquitie, and by past practise: and the actings of the present House of Commons, untill brought under force, to proclaim the quite contrary. 3. If nothing, ab origine, can be shewed for that, did the King that summoned this Parliament, or the People that chose this House of Commons, supposed in the Case, passe over any such prerogative to them de novo; If either of them did, let us hear how. 4. It is too grosse an absurdity to be charged upon the supposed present, and all former Representatives; that being intrusted by the people with the sole Supremacy, they have of themselves associated to them the King, and the House of Peers, it being beyond the power of the constituted, and onely in the Constitutors to make such an alteration in the fundamentall Constitution; as Representatives cannot make Representatives or Proxies, so can they not take in Associates, or advance others, not impowered by them that impowered them into a Collegueship with them. I leave it therefore to every Reader to determine the Case, and passe Judgement. Whether the sole supreme Power, in the presupposed party, be derived to them legitimately, or be not a Self-created-power, and so a meer Usurpation, and that of the fullest dimension; being against a lawfully settled Government, in prejudice both of the just Magistrates and the people: and in contradiction to both the single tye of Subjects Allegiance to Soveraignty, and the sacred sanction of Vows, Oaths, and Religious Covenants.

Of yeelding obedience to a Power usurped at abovesaid. That it is not lawfull to give up ones self to the Allegiance of such a Power.

COncerning Obedience to an usurped Authority, I meet with two opinions, which I shall severally examine. 1. Is of those who hold obedience as due, and necessary; and that in as full a manner to such, as it is to the lawfullest Power. This is held, and argued for in a Tract, entituled, The lawfulnesse of obeying the present Government: as also in A Discourse, wherein is examined, what is particularly lawfull; &c. By Ant. Ashcam Gent: See in his 2d. Part, cap: 9. Although indeed they both propound their opinion in the Title of their Discourse for obedience as lawfull; yet, in the prosecution, they plead for it in that fulnesse of latitude as due, and necessarie. This their Tenent they strive to maintain in relation to the present State of England. I shall deal with it in reference to the case above proposed, and in thesis 2. Is of those who, reserving their obedience as due and devoted to the lawfull Power, supposed to be still existent; do yet conceive they may submit and act under a usurped Power for the time, and during the intervall of its prevalency.

I begin with the former; wherein it is asserted by one of the foresaid Authorsa, (nd the other comes not short of him in the sense and current of his Discourse) That upon the issue of a warre, and the Expulsion of a just party, a man may lawfully give up himself to the finall Allegiance of the unjust party. Against this Position must my Judgement stand, which dictates to me that I owe no obedience to an Usurper; and to yeeld up my self in obedience or Allegiance unto Usurpers, who have no other title but their usurpation, is unjustifiable, and unlawfull, and that upon these grounds.

1. I cannot (if I would) yeeld up my self in obedience to him that hath no authority over me; take him as a Usurper, and my Allegiance is incompatible to him; obedience and authority; Magistrate, and Subject, are tearms of relation, and do Se mutuo ponere & tellere: they are inseparable from one another; if there be no Magistracy in him, there can be no obedience properly, and formally in me to him. I may (either warrantably or unwarrantably) do an act possibly which he commandeth, but that cannot be truly and properly said to be an act of obedience to him: his authority is null, of no realityb. He is no Magistrate, but a private person; my fellow Subject, (if one of the Nation) or a forreiner to me; his commanding over me and others is, as if a private Souldier should take upon him to give orders to his Company, or an inferiour Officer to an Army; or a servant should offer to rule over his fellow-servants.

In saying he is a usurper, you say enough for the nullifying of his Authority, and my obedience; whatever strength he may have to compell, he hath no Authority to command me: He is a Magistrate that hath the Subjects committed to his charge and care, say the Leyden Divinesc in their Synopsis, and principality, Lypsiusd defines to be, A government delivered by Custome, or Law, and constitution to him that sustains is; and undertaken and managed by him for the good of the Subjects. Another defines a Magistrate to bee A publick person, elected by succession, let, or suffrage; which hath the right and power of Consultation, Judgement, and Command.

2. I may not (if I could) yeeld up my self as a Subject to the Usurper; in so doing, I should take away the right of the lawfull Magistrate which he hath over me, and injure him in the allegiance which I stand tyed in to him, and he still retaineth the claim of at my hands. The Magistrate is (in the case in hand) granted to be in being; he is but deprived of possession and enjoyment, not of property or title; he is yet standing in the relation of a Magistrate to me; and is onely outed of his station perforce. The obedience of a Subject is not so arbitrary, or loose a thing, as that I may place and remove it at pleasure, or as affairs go; but it is a debt which I must render to him unto whom it is due.Rom. 13. 7. Neither is Soveraignty so common, ambulatory, or prostitute a matter, as that its title ceaseth unto him that is violently extruded, or dispossessed of it, and becometh any ones that by force captivates it to himself; the expulsed Magistrate still standing upon his claim and right, and the power in possession having no title but his injurious and forcible entrance; the Subject is not disobliged from him that is expelled, nor at his choice to transfer his obedience to another, neither can the violent intruder challenge it. But in respect of the consequence of that which I here assert as unto resolution in this case, and for that I find the Gentleman, in the afore-named Discoursef positively delivering the direct contrary to it; and that which is (as I think) very strange doctrine both in Christianity and politiques, viz: That we are bound to own Princes so long as it pleaseth God to give them power to command us; and when we see others possest of their Powers,Part. 1. Chap. 5 page 22, 23. Part. 2. cap 9. page 90. we may then say, that the King of kings hath changed our Vice-royes; And further, that the point of right is a thing alwayes doubtfull;—possession generally is the strongest title that Princes have. And if possession was really the truest evidence to us of their (to wit, the expelled Princes) rights, then it is equitable to follow it still, though it be perhaps in a person of more injustice then they were. And the other book, I before cited, (viz: The lawfulnesse of obeying the present Government) maintains the same thing (both whose arguments, for what they say, I shall take notice of, when I have layed down mine own sense and Reasons) I shall therefore here labour to make good these two things: 1. That meer forcible extrusion deprives not any lawfull Magistrate of his right and title to supreame Power. 2. That violent possession gives no right to the Seat of Authority; and consequently the Subjects allegiance is not turned about by the changes of powerfull possession, and dispossession.

1. Forcible extrusion or dispossession divests not of Dominion, that the state of the Subjects allegiancee should be altered by it.

First, if the vindication or recovery of a Princes, or peoples right of Dominion, out of which he, or they are elected, or excluded be a justifiable ground for his, their, and others in their behalf leavying and waging war, and prosecuting with the sword those that withstand the said recovery; then the right of him that is expulsed by force is not cancelled, or disanulled. The reason of this consequence is of it self evident, for nothing can be the ground of a war but a just and reall title, either to be defended, or recovered; but I assume, the recovery or redemption of a Princes or peoples right to a Kingdome with-held, or wrested from him or them, is a just ground of drawing the Sword, and commencing a war. This is proved (if it needeth any proof) by the war of the Judges & people of Israel, against the Kings and Nations that at severall times invaded and ruled over them; against whom they rose up, and rescued themselves, and the Dominion of their Land from them: the story of which acts, we have in the book of Judges, and by the warres of Samuel and Saul against the Philistines recorded in the 1. Book of Samuel: as also by Davids warlike undertaking against, and suppression of Absolom, who had carried away all Israel after him, into a Rebellion against David, & expulsed him out of the Land, 2 Sam. 15. &c. and 19. 9. In like manner by Jehoiada’s and the peoples rising in Arms against Athalia, the usurping Queen, in the right of Joash; and their suppressing, and destroying her,1 Macca. chap. 1. &c. and enthroning him by force of Arms. 2 King. 11. And by the wars of the Maccabees against Antiochus, Epiphanes, and his successors.g And the many undoubtedly lawfull wars of other Princes and States in such causes as these, which to insist on is superfluous in so clear a matter.

Secondly, If right and title to Soveraignty be not built upon possession, but upon the Law of the Land, or other consent of the people, then it is not lost by dispossession; this consequence is founded upon that which a learned Statisth saith, Is a received maxime almost unshaken, and infallible, Nihil magis nature consentantum est, quam ut iisdem modis res dissalvantur quibui constituantur: There is nothing more agreeable to nature, then that things should be disolved by the same means they are constituted. From which he Infers, very pertinently to our case in hand, That if the part of the people, or Estate be somewhat in the Election, you cannot make them nulles or ciphers in the prorivation or translation. But the right and title of Soveraignty is not built upon possession, (which the proof of the latter Position will clear) but upon the peoples consent, which hath gone for so currant an axiome, especially of late, that it will certainly passe without contradiction.

Thirdly, If a private property be not lost by losse of possession, neither (or rather much lesse) can such a publique property be lost by that means; there can be no such difference made betwixt them as to enervate this consequence, and however, who sees not the incongruitie of this, that that which is the conservatory and protection of a private mans property, should be of a so much more slipperie tenure then it; but a private property is not lost by dispossession, if it were, for what use serveth the Law, or Magistracy? one main end of which hath been, to vindicate the Subjects right from usurpation, or what call you property? But he that either hath any, or granteth such a thing to be as property, will let this assumption passe.

Fourthly, If violent extrusion take away a Soveraignes right, then rebellion where it prospers and prevails is no treason; for there can be no treason, or other crime imputed as against the Crown, dignity, or authority of them, whose right therein is extinct and null; so that they are onely (according to this opinion) traitors or rebels, that rise up in Arms, and rebellion against the lawfull Power, and do not succeed and speed according to their desires. By this account, treason and rebellion shall consist, not in the maliciousnesse of the intent or attempt; but in the misfortune of successe, or impotency of the prosecution of it.

Fifthly, If force dissolve Magistracy; then that prohibition of resistance under pain of domination. Rom. 13. 2. is in vain, in that it concerns onely them that cannot resist effectually, and is no more then if he had said, resist not ye that want power to do it, lest if ye do, ye incur damnation: for they that have power, and please to use it to the deposing of the Magistrate, being that in so doing they put an end to his fight, how can guilt remain on them?

2. Violent intrusion into, and possession of the Seat of Authority gives no right to it; and consequently neither draws allegiance after it, nor evacuates it in relation to another.

First, an unjust action cannot produce, or create a right.i Morall good, and evill are at such distance, that the one cannot be the cause, the other the effect; but violent intrusion into Authority is an unjust action: Luk. 12. 14. Man who made me a Judge, &c. and that whether it be by one that should be a Subject to that power, Rom. 13. 2. Whosoever therefore resisteth, &c. ver. 5. Wherefore ye must needs be subject, &c. Tit. 3. 1. 1 Pet. 2. 13. or by a Forreiner, Judg. 11. 12. 27. 2 Chron. 20. 10.

2ly, If violent occupation made a right;k then it were lawfull for any, that could make a sufficient strength for it, to rise up in Arms, invade, and seise on any Kingdome or Territory, he can prevail over; yea to kill and destroy men and Countreys for Empire and Dominion, asl Cæsar inclined to hold; for that which is of it self the way and means to place a man in a lawfull estate, or calling, and makes him a lawfull possessor of it, must needs be lawfull: but it cannot be held lawfull for any, that can finde power, and advantage, to invade Crowns and Countreys, as is evident by the proof of the Assumption of the preceeding Argument.

3ly, If possession by power give a title; then its unlawfull for an oppressed Prince, or people to raise warre, or use any other means to expell an Invader, or remove such as have come in, and hold meerly by force; for its unlawfull to resist, or fight against a just Magistrate, Rom 13. 1, 2. But it is lawfull for an oppressed Prince or people, by Arms, or otherwise to free themselves from a forcible Usurper, as manifestly appeareth by those presidents given in the proof of the assumption of the first argument for the former Proposition, to wit, the wars of Israel in the book of Judges, and 1. of Samuel, of David, Jehoiadah, and the Maccabees, and by the known Law and practise of all Nations, and consent of all Divines, and Christians, who with one vote allow defensive and recuperative Arms, excepting the Anabaptists, and some ancient Hereticks of their stamp.

4ly, All force ought to presuppose a right in that about which it is conversant; whether for the defence or recovery of its wars (saith Francis Lord Verulam,m &c.) (I speak not of ambitious predatorie wars) are suits of appeal to the tribunall of Gods justice, when there are no superiors on earth to determine the cause, and they are as civill Pleas, either Plaints or Defences: Force therefore cannot create a right, seeing it is to follow it, and both give it the precedencie in time, and own it as its ground-work; Adde to this, that the Sword is committed to the Magistrate (and to him alone, saith Peter Martyrn) as its subject or owner; so that the Magistrate is before it, not made by it. The Sword makes not the Magistrate, (that is, it is not its principle of Generation,) but the Magistrate à warranto authorizeth the Sword; the sword may make for his conservation, but not for his Creation.

5ly, If force give a title (renitente populo) then that late so much decantated Aphorisme, All Power (to wit, Authority) is from the People, must be called in again; yea all Donations, Elections, Compacts and Covenants betwixt Prince and people are void, and null businesses. A third person that can get hold or power, and lists to usurp, may dissolve and evacuate them all; yea the Prince that comes in by them, when once he hath possession of the Power, holds by his power, and not by them, and can no longer, nor further look to retain his right to Authority then he can enforce it; and what Turkish and tyrannicall practises doth this doctrine put him upon of necessitie, if he will sit fast.

Mr. Ashcam part. 1. ca. 2. Sect. 4.6ly, No man naturally is more a Magistrate then another: Magistracy being in truth not a naturall, but a civill relation; as is that of husband and wife, master and servant: it must therfore be founded on some mutuall and reciprocall act, or agreement of both parties, to wit, Rulers and Subjects; and cannot result out of the action of one alone of them, nor can neither partie be meerly passive, in contracting such a relation. A mutuall civill obligation cannot arise but of the joynt or interchangeable concurrance of both.

7ly, Power and right, as also possession and right, are separable, as all experience demonstrates; so it was in the controversie betwixt David and Absolom, and so it frequently happens to be: successe and victory doth not seldome follow the wrong party; and he would be thought irrationall amongst all men, wheresoever in the world, but where reason it self is brought under tyrannie, that should say, successe is the onely Arbitrator of Controversies of right, and is ever infallible.

8ly, Strength and Authority also are two distinct and separable things, and rarely meet in the same subject, but where either bruitishnesse, or all miseries prevail; man hath dominion given him over the beasts, many whereof are (and were by creation) stronger then he; What is a Generals natural strength to that of the Army over which he commands? What is a Kings, or a Counsels personall strength to that of the body of the people over which it sways? yea what is the hand in the naturall body to all the members under its government, in point of force? We see a small board or two, put in the place of a rudder, guides the whole vessel. Amongst some beasts indeed the strongest rules; but amongst men it is not regularly so: yea, among some unreasonable Animals, not force, but fitnesse designed by Election obtains the rule. Bees, they say, choose their king, of whomo Plinie observes, that either he hath no sting, or Nature hath denyed him the use of it; being onely armed with majestie. And Aristotle saith,p It is by a kinde of naturall equitie and merit, that he that is of a sage and disercet understanding should rule; on the other hand he should obey, and be in subjection, that hath more strength of body, and Arms to perform service.

9ly, Where there is no title but power, there can be no rule for Government but power and will: onely that which gives right to Magistracy must set bounds to it; how can they be tyed to Laws, in exercising Government, that are tyed to none in coming by it? If the basis or bottome of Government be power, that must also be the measure of it;q so that a Magistrate, so holding, is confined to no justice, or Law; restrained from no violence, or sacriledge that his Power may extend to. That power, against whose forcible intrusion the Laws, and Constitutions made by Prince and people, for the settling of the Crown or Soveraigne rule, are of no validity, can reasonably have no obligation upon it from any other Laws made by the same parties;r the Authority that makes the Law is the Soul that quickens it; the Law springs from Authority, as the act doth from its habit or principle; so that grant, or prostitute Authority to the Sword as its right, and you subvert all settled Laws, whether fundamentall or superstructory; and this all experience, as well as reason, dictates; for where, or in what Age did meer force assume the Empire without a lawlesse arbitrarinesse challenged to it self?

10ly, If you yeeld the Sword such a right where it can be master in the publick or civill State; why should it not have the same interest in the private, domesticall, and personall? So that pyrates, theeves, and robbers, may justly claim a right to that which they can lay their hands on, and be accountable to none for their spoil and rapine.

[Editor: illegible text]11ly, Whereas the Apostle to the Romans Chap. 13. 2. forbiddeth resistance (or contraordination) to the lawfull power ordained of God, and that upon pain of damnation to be received by him that doth it, if force give a right to that power; his action, that resists with victory, shall be justifiable, and the resister shall gain a Crown instead of receiving damnation; and none shall fall under the guilt and penalty of resistance, but he that offers to resist, and cannot make it good. The sense then which this Position puts upon this text is catachresticall, and it glosseth the words so, as to be an incouragement to resist the power, for he that resisteth the power prosperously (according to it) possesseth justly that ordinance of God, and in truth purchaseth to himself (not damnation, but) domination.

Having thus, I hope, sufficiently cleered the duty of Allegiance to be not the violent intruders, but the oppressed and violently extruded Magistrates; I shall proceed to other Reasons against Subjects giving up themselves to the obedience of a usurping party.

3. If I should do that, I should yeeld assistance to the Usurper in his wrong doing, and usurpation; and so become a partaker of his sin: obedience to one, as the supreame Magistrate, is a comprehensive thing, and includes many duties towards him at a power, viz: Receiving Commission from him for offices, or acts otherwayes not competible to me; maintaining and defending him in his power by pay, counsell, intelligence, Arms, and prayers; all which I am bound to yeeld the Usurper, to my power, if I resigne mine allegiance up to him: and how shall I do these things, and not 1. support, and have communion with him in his wickednes. 2. Combine against, betray, and resist the right of the injuriously dethroned Magistrate. 3. And make my self uncapable of obedience, or being a Subject to the lawfull Power hereafter.

4. It were a publick wrong to the Nation I am a member of so to bestow mine allegiance; were I and the Countrey free from all tye of subjection (in the presupposed Case) to the expulsed Magistrate; yet I could not lawfully make such a private bargain of my allegiance, its the part and duty of a particular person in a Nation (that is joyned together as one body politick or Common-wealth) not to choose his head, or supreame Governor by his single election, or vote, but, when a new Magistracy is to be erected, or Magistrate advanced, to attend the common and generall vote of the people, or body politick he is of; solitarily, or with a small party to alter the state and posture of my publick allegiance (in this case) would be sedition, and faction; the current of the people or community I am of it to be followed, at least where they justly dispose of the Soveraignty over them. It was in it self a loyall, and right resolution (had it been in such a case as this, and not misapplyed) which Hushai exprest, Nay, but whom the Lord and this people, and all the men of Israel choose; his will I be, and him will I follow; It would be to me (I confesse) a difficult case, and harder then I will here undertake to resolve, if the body of the Kingdom (in the case in hand) should either collectively, or representatively conspire; notwithstanding their oaths, vows, and Covenants, to abrogate the ancient Soveraigne Power, and to set up the Usurpers; but that’s not the present case, here is no generall consent of the Kingdom presupposed, or pleaded for in behalf of the Usurper; the dispute is about obedience to meer Usurpation. And in this state of things, to leave every man free, to make over his allegiance by himself, is to open a doore to more divisions then ever yet were in any Age, or Nation, and would confound all, not an heptarchy; but a chiliarchy,1 Sam. 10. 27. 2 Sam. 19. 41. 20. 1. or myriarchy might follow. When Saul had a generall vote of the people to be King, they were children of Belial that refused him; and at Davids re-invelling after Absoloms treason, and fall, the men of Israel challenged them of Judah for going about to restore the King without them; the far greater part of the Kingdom, and that man of Belial, Sheba, the son of Bichri, was justly pursued with the sword unto death, for blowing a trumpet of defection from David, when they both had consented to re-advance him.

5. But there is a bar yet behinde, of as main a strength as any yet stood on, to keep back such a submittance to the Usurper, and that is the Oaths, Vows, Protestations, and Covenants presupposed above to be taken by the people, for their owning, obeying and defending the power or Magistracy displaced, and in opposition to whose right the Usurper comes and continues in.

I have hitherto discussed the question in a case without reflection upon any particular Kingdom, or reall Subject; and so I shall do still, onely I shall borrow leave, in the prosecution of this Argument, to presuppose, in the aforesaid Case, the Oaths and Covenant were the same that have been taken in this Kingdom of England. The Author of the book called, The lawfulnesse of obeying the present Government, in his 11. page moveth an inquiry thus: It were good to consider whether there be any clause in any Oath, or Covenant, which, in a fair and common sense, forbid obedience to the Commands of the present Government, and Authority: and proceeding, he onely makes enquiry into one clause of the Oath of Allegiance, which he thives to bow to his sense, and passeth by all besides. I shall speak to what he saith on that clause anon; and shall here onely interrogate, or propound by way of quære, concerning divers clauses in the Oaths, Protestations, Vows and Covenants.

First, concerning the Oaths of Allegiance and Supremacy, whereas in the former, it is sworn, I shall bear faith, and true Allegiance to his Majestie, his Heirs, and Successors: and him and them will defend to the uttermost of my power, against all conspiracies, and attempts whatsoever, which shall be made against his, or their persons, their Crown, or dignity. And in the latter, I shall bear faith, and true allegiance to the Kings Highnesse, his Heirs, and lawfull Successors: and, to my power, shall assist, and defend all jurisdictions, priviledges, preheminencies, and Authorities granted to the Kings Highnesse, his Heirs, and Successors; or united and annexed to the Imperiall Crown of this Realm. First, do not these Oaths binde, whomsoever hath taken them, clearly, plainly, and in terminis to an Allegiance, over-living his Majesties person, and pitched upon his Heirs and Successors; so that he is not free from the Oaths at his Majesties decease, or then left at randome to pay his allegiance to whom he will choose? 2. Do they not intend, by His Majesties Heirs and Successors, the same persons, joyning them together with the copulative (and) and not using the discretive (or) and the former Oath twice comprizing both in the following clauses under the same terme or pronoune, (viz: them, theirs) so that, according to these Oaths, His Heirs, are of right his successors, and none can be his Successor, (whilest he hath an Heir, and longer the Oath lasts not) but his Heir; and If any conspiracy or attempt should be made to prevent his Heir from being and continuing his successor, or to make any one his successor that is not his heir, (if he hath one) is not the Subject sworn, by vertue of this Oath, to continue his allegiance to his Heir as the right successor, and to defend him in that his right to his uttermost? 3. And doth not the tearm (lawfull) annexed to Successors (in the Oath of Supremacy) manifestly exclude all cavill of a distinction betwixt Heirs and successors; the word (lawfull) (whether you interpret it of legitimation of birth, or proximity of succession in regard of line, according to the Law of the Land, entailing the Crown upon his Majesties issue; or rather both the latter including the former, restraining successors from meaning any other then his heirs? 4. And do not both these Oathes binde the swearer to assist and defend to his uttermost power, against all attempts, Monarchy, or the Kingly Office, and Government (in the race of his Majestie) cleerly expressed by many tearms, to wit, Their Crown or dignity, all jurisdictions, priviledges, preheminences, and Authorities, granted to the Kings Highnesse, his heirs, and successors, or united, and annexed to the Imperiall Crown of this Realm. How then can he yeeld obedience to them that are not his heirs, nor lawfull successors, nor do so much as wear his Crown, or sway the Regall Scepter? How can he not oppose, and withstand them in the assistance and defence of the right of his Majesties heirs and lawfull successors?

2. Concerning the Vow and Protestation of the 5. of May, 1641, and the Solemn League and Covenant. 1. How can any that hath taken the said Protestation according to it, maintain and defend the true Protestant Religion, expressed in the Doctrine of the Church of England, against all Popery, and Popish innovations within this Realm, contrary to the same Doctrine; and yet yeeld obedience to an usurping authority, coming in, and holding in derogation of, and opposition to the lawfull Prince; when as the publick doctrine of that Church (layed down in the 2. Tome of Homilies, and the last Homily thereof approved of by the 35. Article of Religion) fully and flatly refuteth, and condemneth any Subjects removing, or disposing their Prince, upon any pretence whatsoever?

2ly, How can any man according to the Protestation, maintain and defend, the power and privileges of Parliament, and according to the Covenant preserve the rights and privileges of Parliament; and yet yeeld obedience to a small party of one of the Houses of Parliament, as the Supreame Power, the said party excluding the rest of that House, and the other House wholly; and deposing the lawfull Prince, and abolishing the Office of the King, whose presence, personall, or legall, and politicall, hath been declared inseparable from the Parliament, and joyning with an Army, that with force hath demanded, and carried on these things?

3. How can be, according to the Protestation, maintain and defend the lawfull rights, and liberties of the Subjects, and, according to the Covenant, preserve the liberties of the Kingdom; and yet obey, and own a meerly usurped power. Whereas the most fundamentall civill Liberty of a Kingdom, and Subjects is to have a Government over them, set up by the constitution, or consent of the people; not obtruded on them by those, who of their own will and power, without any calling from them, assume it to themselves?

4. How can he, according to the Covenant, preserve and defend the Kings Majesties Person, and Authority, &c. and yet yeeld obedience to those usurpers, who, after his death, cast down his Authority, and place themselves instead thereof as the Supreame Power; whereas his Authority, in the plain intention of the Covenant, is to be preserved and defended beyond the tearme of his life, and in his posterity; as it appears from this clause compared with those words in the preface, Having before our eyes the glory of God,—the honour and happinesse of the Kings Majestie, and his posterity?

5. Lastly, how doth he, according to the Protestation, to his power, and as far as lawfully he may, oppose, and by all good wayes, and means endev’ur to bring to condigne punishment all such as shall either by force, practise, counsels, plots, conspiracies, or otherwise, do any thing to the contrary of any thing in this present Protestation contained; and, according to the Covenant, not suffer himself directly, or indirectly, by whatsoever combination, persuasion, or terror to be divided, or withdrawn from this blessed Union and conjunction; whether to make defection to the contrary part, or give himself to a detestable indifferencie, or neutrality in this cause, which so much concerneth the glory of God, the good of the Kingdome, and honour of the King, but, all the dayes of his life, zealously, and constantly continue therein against all opposition, and promote the same, according to his power, against all lets and impediments whatsoever, that yeeldeth allegiance, and obedience to a party standing, and leading all those that agree to obey them in so palpable contradiction, and opposition to some materiall points, and concernments of Religion, divers most fundamentall rights of the Parliament and people, and all the Authority and whole being of the King, contained and covenanted for, in the aforesaid Protestation and Covenant respectively.

The question discussed, Whether submission to, and acting under a usurped Power for the time, be lawfull, with a reservation of Allegiance to the lawfull Power supposed to be expulsed.

I Now come to enquire into the other opinion before mentioned, viz: That one may submit, and act under a usurped Power, for the time, and during the intervall of its prevalency; with reservation of allegiance, as due and cordially devoted to the lawfull Power expulsed. And about this we shall not insist long, because we finde not much contestation or difficulty.

In regard of the justnes, and necessity of some things which may be the subject, or matter of the Usurpers command, and the Arbitrarinesse of others, and the lawfulnesse of either, not depending upon the command or warrant of a superior, but resulting out of the nature of the action it self; so that a private man might do it, were there no Magistrate to command it, or no command from the Magistrate for it. We must needs grant, there are things which may be done upon the Usurpers command or injunction, (though not because or by vertue of it) for the command of him that unwarrantably assumeth power, cannot, by it self, make that unlawfull which were lawfull if that were not. For instance, the performance of acts of common equity, charity, order, publick utility, and self-preservation is requisite: suppose it be in concurrence with a Usurpers command, and in thus doing we do materially, but not formally obey him; the ground of acting, in such things, being not at all any relation, or principle of subjection to him; but conscience of obedience to the will of God, and doe respect to others, and our own safety, and good. Under this sort of actions I comprehend:

1. Taking up Arms for the preservation of our selves and the Countray against a common Enemy, upon the Usurpers summons; the which we might do of our selves, were there no Authority; or if a just Authority were in being, yet if it could not, or did not, maturely enough call us forth to it.

2. Payment of taxes, and bearing other impositions for the usurping Power, where, and while we are under his compulsive power, because such contributions may, and will be taken whether I will pay them or not; and I yeeld them under his enforcement, as a ransome for my life, or liberty, or somewhat else that is better to me then the payment; and consequently I am to choose the parting with it as the lesse evil, rather then with that which is better, which to loose is to incur a greater evill for the avoidance of a lesse. In this point Mr. Ascham, the afore named Author, (Part. 2. Chap. 1. page 35.) determineth well (had he not contradicted (as I understand him) that he delivers in this and the next Chap. with that assertion of his part. 1. cap. 6. page 25.) distinguishing rightly betwixt that which cannot be had, nor the value of it, unlesse I actually give it; and that which may be taken whether I contribute it or no. Of this latter kinde is paying of Taxes in this case;a herein I am but morally passive, as a man that is fallen into the hands of a pack of bloodie theeves; and, being demanded it, takes his purse out of his pocket, and delivers it to them, though with his own hand (saith that Author) he puts his purse into their hands, yet the Law cals not that a gift, nor excuseth the thief for taking it, but all contrary. Or a man, apprehended by a party of the invading Enemies, or Usurpers Army, walks or rides along with them to their muster or battell, when as he cannot escape them, and otherwise they would draw him. But it is commonly objected thus. Obj. This payment or other charge is taken, and will be used to an evill use as to maintain Usurpation. R: But that’s beyond my deliberation, not in my power to prevent; it will not be avoided by putting them to force it from me, but rather more gain will accrue to them, and damage to me, if I stand out; my denying will be made an occasion by them to take more: this case is like that of entering into a Covenant with those that in covenanting we know before hand will swear by a false god, wherein, Divinesb resolve, the partie swearing by the true God participateth not in his sin that swears by a false one, in as much as he communicates with him in the Covenant, not in the oath taken on his part, and provides thereby for his necessarie security; and thus did Abraham, and Jacob, in their respective Covenants with Abimelech and Laban.

3. Complaining, petitioning, or going to Law before the Magistrates or Courts authorized by the Usurpers. (Provided, you give not the Usurpers, to whom you petition, such Titles as you give to the lawfull Magistrate.) In thus doing, I seek my necessary self preservation; neither do I yeeld,Excusantur à peceato inducendi tyrannutn ad actum, & opus ilicitum petentes ab illo iustitiam quia non retunt actun illititum, sed justitam illius ottin illiciti pie interpre. tandx sunt petitiones tam iustitiæ quam tionestu uratiæ quæ ofteraneur Tyrannis, seillcerss vis, seu ex que vis detinere, & exercere hoc diminium, utere illo juste, utere honesle, utere pie, utere ad utilitatem publicam, & priratorum, prout deceret dominium nec intendunt, nec petunt actum usurpatum, led qualitattm iamctam inactu usurpato exercendo. Caietam Iummula, Tit. Remp. tyrannice, &c. or ascribe to them to whom I have recourse any just power of judicature, or participate in their sin of usurping it; onely I acknowledge they have might and ability in their hand to right me; which, though they ought not to assume, yet I may take the benefit of their unjust use of it; as a poore man may receive relief at the hands of him that hath gotten those goods he distributeth unjustly; and I may receive my money, with a good conscience, from the hands of a thief that is willing to return it to me, though he took it by robbery, from another thief that robbed me of it; and if the party, with whom I have a controversie for my right, will agree to refer the matter, betwixt us, to a private person as an Arbitrator, and stand to his arbitrement; that is a lawfull means of coming by my own, though by his help, and award that hath not claim of Authority over me; my submitting therefore my private right to the judgement of an usurping Magistracy, is no placing or owning a publick power of judicature to be in him. It hath been ordinary (and there is no doubt of the lawfulnesse of it) for a Souldier to ask quartor, a prisoner liberty, a man his plundered goods of his Enemy: yet in all this there is no concession of a legall power in that Enemie to be a Judge over the said Petitioners, either in case of life, goods, or liberty; onely in the form of addresse to the Usurper, we had need be cautelous that such a style be not used as will be a plain concession of his title to the power which he usurps.

But, in granting liberty of concurrence with some commands of an usurped Authority, we neither yeeld any obedience at all to be due, or performable to it; nor can we allow a correspondence with it in divers things, and therefore we are to put a difference.

First, betwixt things that are in themselves necessary, and those that are of a middle or an indifferent nature in themselves considered. In the latter; though, in some cases, I may act upon the Usurpers injunction; as our Saviour payed tribute where he was not bound to it, to avoid scandall; yet I must be cautious, 1. of owning, justifying, or upholding the usurpation, or injustice of the party commanding, the very appearance whereof I must as much as I can avoid. So did our Saviour, in paying the tribute gatherers their demand, by declaring his freedome, and the consideration upon which he payed, viz: not the equity of the demand, but his willingnesse to prevent scandall. And therefore in the observing of a duty of Religion, necessary in it self, and appointed, by unjustifiable Authority, to be kept on such a set day, which is in it self, arbitrary, the best way is, to take another day for it, for the shunning of the appearance of the evill of obeying an unjust power. 2. Of doing any thing that I may foresee will bring a worse scandall being acted, then the omission of it would; it being required of a Christian, where scandall-takeing lyes both wayes (as not seldome it doth) to shun the offence that is of worse consequence, which is usually that which is more generally taken, or by persons more considerable, or worthy of tender respect. The Apostle Paul, condemning Judaisme in Peter, and others at Antioch, practised in favour of a few, where the most part were Gentlle Christians, Gal. 2. 11. &c. but admitted it at Jerusalem, where the greater sort were beleeving Jews, Act. 21. 20, &c.

2. Betwixt morall, or prudentiall acts competible to private men, or subjects, and politicall acts, or judiciall proceedings that flow from power, and Authority inherent in the person that acts them, or are the issues of distributive justice, and either come forth from a person clothed with Government, or unto which is requisite a stamp of Authority to make them lawfull, and justifiable: as to bear the office of a Magistrate, or Commander in Civill or Military affairs, or to be any under Agent, or servant in carrying on, or assisting the Government. An Usurper, in giving out Commissions, Commands or Warrants for proceedings of this nature, I conceive may not, in this kinde, be obeyed. Men are not to act as subordinate rulers, or agents, under such a power, or as sent by him as supreame in the Apostles sense, 1 Pet. 2. 14. For,

1. The Usurpers authority being indeed null, and of no effect, he being in truth but in a private mans capacity, as to the power he assumes; he cannot communicate, or derive any authority unto me, whereby I may act, that which before I could not; so that those actions, which require the seal of Authority to make them lawfull, and which without it would be irregular and sinfull, it must needs be clearly unlawfull for me to do, by vertue of his Commission. Conscientious advised men will generally judge it presumption, violence, oppression, bloodshed, respectively for a private man to take upon him of himself, to imprison, chastise, amerce, or put to death any supposed, or really manifested malefactor; and if I have no other humane warrant but the Usurpers, it leaving me but in a private mans capacitie, will leave my actions of that nature under no better a character. If I should, being about such undertakings, be asked that question of our Saviour, Lick. 12. 14. Man, who made thee a judge, or a divider over us? What satisfaction would it be to him that so enquireth, or to mine own conscience to alledge the name of the Usurper, who, as to supreme Authority, and consequently to the making of a competent Officer of Justice, is as good as no body.