Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics Vol. 6 (1649) (2nd ed)

Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics, Volume 6 (1649) (2nd. revised and enlarged Edition)

[Note: This is a work in progress]

Revised: 26 May, 2018 - 53 titles, of which

- 27 are corrected titles from 1st ed.;

- 5 titles from Malcolm collection; 3 Milton texts

- 13 additional titles from LT9 and 3 from LT10 (of which 12 still need to be corrected)

Note: As corrections are made to the files, they will be made here first (the “Pages” section of the OLL </pages/leveller-tracts-summary>) and then when completed the entire volume will be added to the main OLL collection (the “Titles” section of the OLL) </titles/2595>.

- Tracts which have not yet been corrected are indicated [UNCORRECTED] and the illegible words are marked as &illegible;. Some tracts have hundreds of illegible words and characters.

- As they are corrected against the facsimile version we indicate it with the date [CORRECTED - 03.03.16]. Where the text cannot be deciphered it is marked [Editor: illegible word].

- When a tract is composed of separate parts we indicate this where possible in the Table of Contents.

For more information see:

- Summary of the Leveller Tracts Project </pages/leveller-tracts-summary>

- The Complete Table of Contents </pages/leveller-tracts-table-of-contents>

Table of Contents

-

Introductory Matter (to be added later)

- Introduction to the Series

- Publishing and Biographical Information

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

-

Editorial Matter (to be added later)

- Editor’s Introduction to Volume 7 (1650-60)

- Chronology of Key Events

- Tracts in Volume 6 (1649)

- [CORRECTED - 24.04.18 - 1 illegible] T.173 (9.35) Marchamont Nedham, The Great Feast at the Sheep-shearing of the City and Citizens (1649).

- [UNCORRECTED - 1627 illegibles] T.176 (10.15) [Richard Overton], The Moderate (December 1648 - January 1649).

- no. 21 (Nov. 28 to Dec. 5, 1648) to no. 33 (Feb. 20-27, 1649)

- [RE-CORRECTED - 24.04.18] T.288 (M8) John Goodwin, Right and Might Well mett (1 Jan., 1649).

- [UNCORRECTED - 17 illegibles] T.177 (9.36) Anon., The Peoples Right briefly Asserted (15 January, 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.178 (6.1) Anon., The humble Petition of firm and constant Friends to the Parliament (19 January 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.179 (6.2) John Rushworth, A Petition concerning the Draught of an Agreement of the People (20 January 1649).

- To the honorable the Commons of England in Parliament assembled; The humble Petition of his Excellency Thomas Lord Fairfax, and the General Councel of Officers of the Army under his Command

- AN AGREEMENT OF THE PEOPLE OF ENGLAND, And the places therewith INCORPORATED

- A Declaration of the Generall Councell of Officers of the Army

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.271 John Milton, The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (Feb., 1649).

- [CORRECTED - 20.04.2018 - 11 illegibles] T.180 (9.37) John Warr, The Priviledges of the People, or Principles of Common Right and Freedome (5 February, 1649).

- [UNCORRECTED - 86 illegibles] T.181 (9.38) John Canne, The Golden Rule, or Justice Advanced (16 February, 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.182 (6.3) John Lilburne, Englands New Chains Discovered (26 February 1649).

- [UNCORRECTED - 12 illegibles] T.183 (9.39) [W.J.], A Dissection of all Governments (1 March, 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.184 (6.4) [William Walwyn], The Vanitie of the present Churches (12 March 1649).

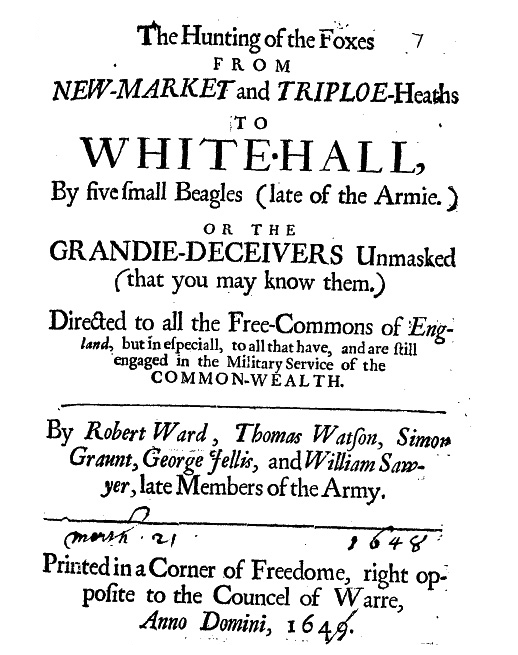

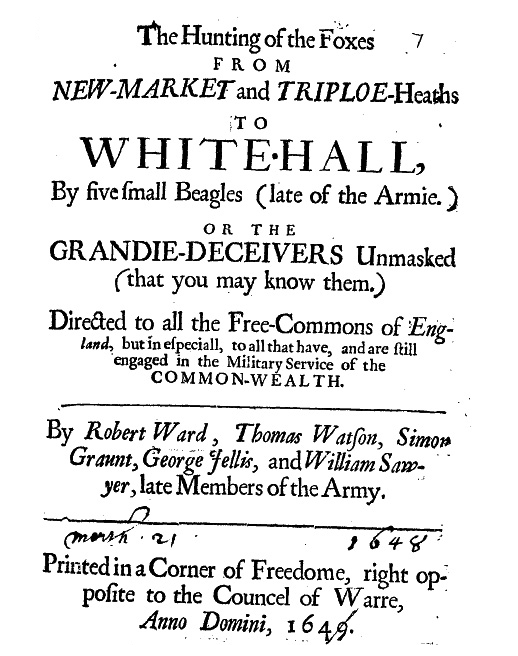

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.185 (6.5) [Signed by Robert Ward, Thomas Watfon, Simon Graunt, George Jellis, William Sawyer (or 5 “Beagles”), but attributed to Richard Overton or John Lilburne], The Hunting of the Foxes (21 March 1649).

- The Hunting of the Foxes, etc.

- To his Excellency Tho. Lord Fairfax, and his Councel of Officers

- The Examination and Answers of ROBERT WARD, before the Court Martiall, March 3. 1648 (and others)

- To the Supreme Authority of the Nation, The Commons assembled in Parliament: The humble Petition of the Souldiery under the Conduct of THO. Lord FAIRFAX. (24 March, 1649)

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.289 [1649.03.22] (M10) A Declaration of the Parliament of England (22 March, 1649).

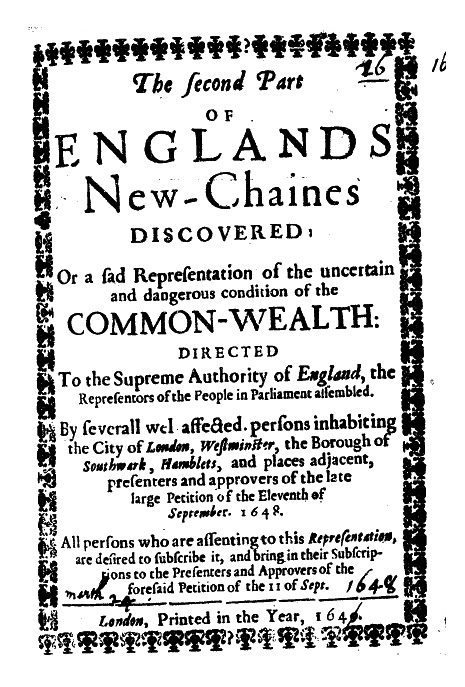

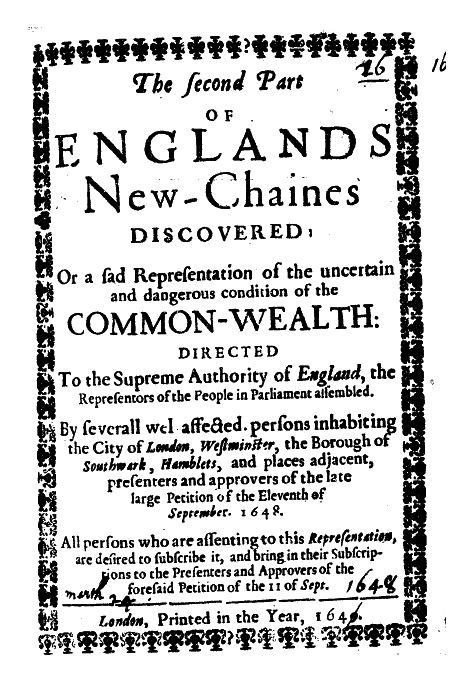

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.186 (6.6) [John Lilburne], The Second Part of Englands New-Chaines Discovered (24 March 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.187 (6.7) John Lilburne, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton, The Picture of the Councel of State (4 April, 1649).

- John Bradshaw, The Narrative of the proceedings against Lieut. Coll. John Lilburn

- Lilburn, To the Lieut. of the Tower of London.

- Lilburn, Postscript

- Overton, The Proceedings of the Councel of State against Richard Overton, now prisoner in the Tower of London

- Postscript

- Prince, The Narrative of the Proceedings against Mr Thomas Prince

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.188 (6.8) [William Walwyn], The English Souldiers Standard (5 April 1649).

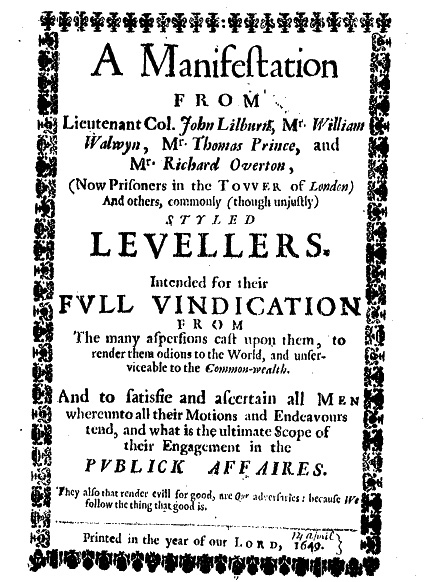

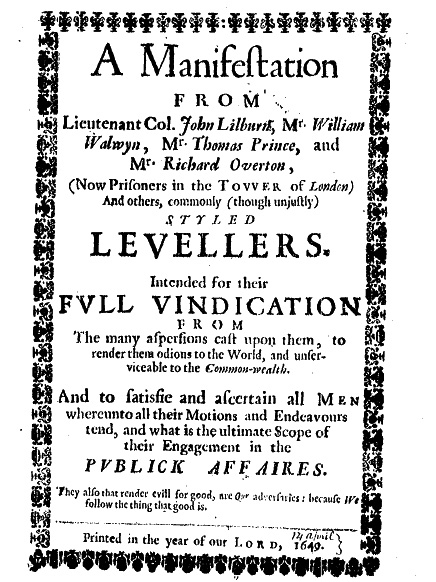

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.189 (6.9) [Signed by John Lilburn, William Walwyn, Thomas Price, Richard Overton, sometimes attributed mainly to Walwyn], A Manifestation from Lieutenant Col. John Lilburn et al. (14 April 1649).

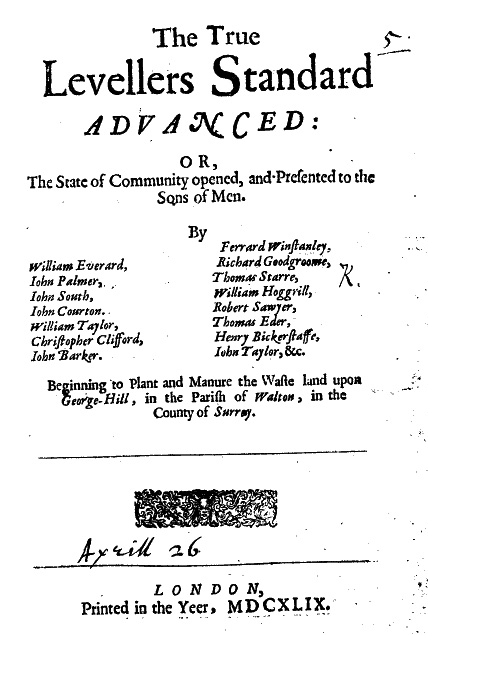

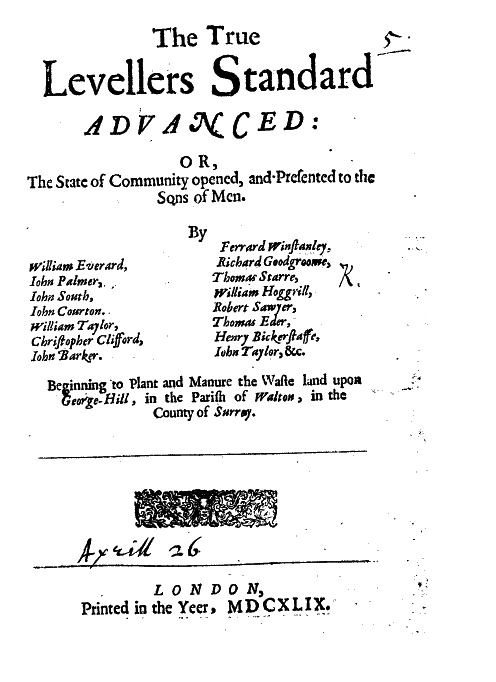

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.174 (6.26) Gerrard Winstanley, et al., The True Levellers Standard Advanced (20 April, 1649).

- Introduction by John Taylor

- Main text: A Declaration to the Powers of England (on digging up George-Hill in Surrey)

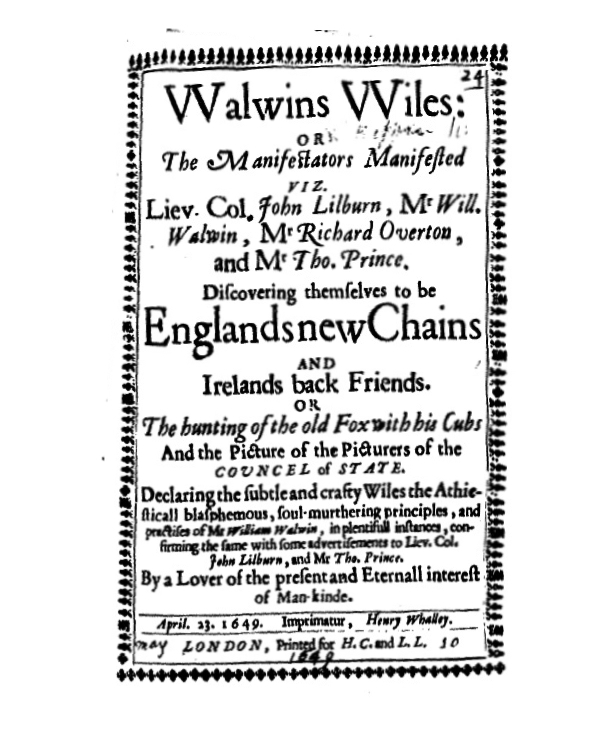

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.190 (6.10) [John Prince], Walwyns Wiles: Or The manifesters Manifested (23 April 1649).

- The Epistle Dedicatory: To the Noble and Successful Englands Army, Under The Command of his Excellency Thomas Lord General Fairfax

- Walwyns Wiles: or The Manifestators Manifested

- Postscript

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.290 [1649.04.25] (M11) Francis Rous, The Lawfulness Of obeying the Present Government (25 April, 1649).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.272 John Milton, Observations upon the Articles of Peace with the Irish Rebels (May, 1649).

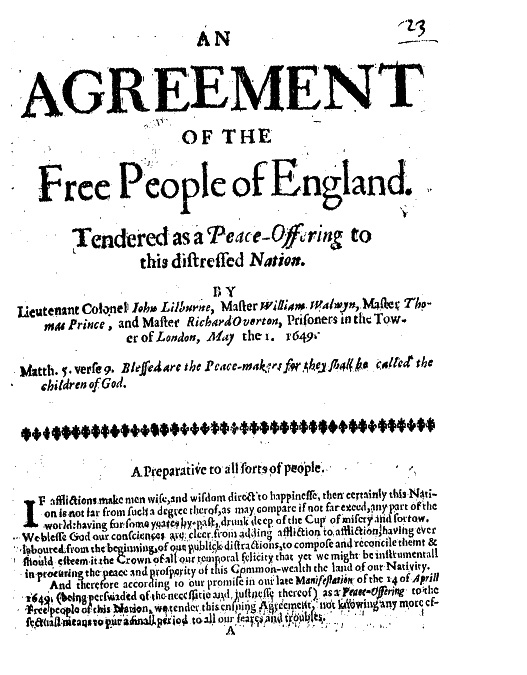

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.191 (6.11) John Lilburne, William Walwyn, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton, An Agreement of the Free People of England (1 May 1649).

- A Preparative to all sorts of people

- The Agreement it selfe

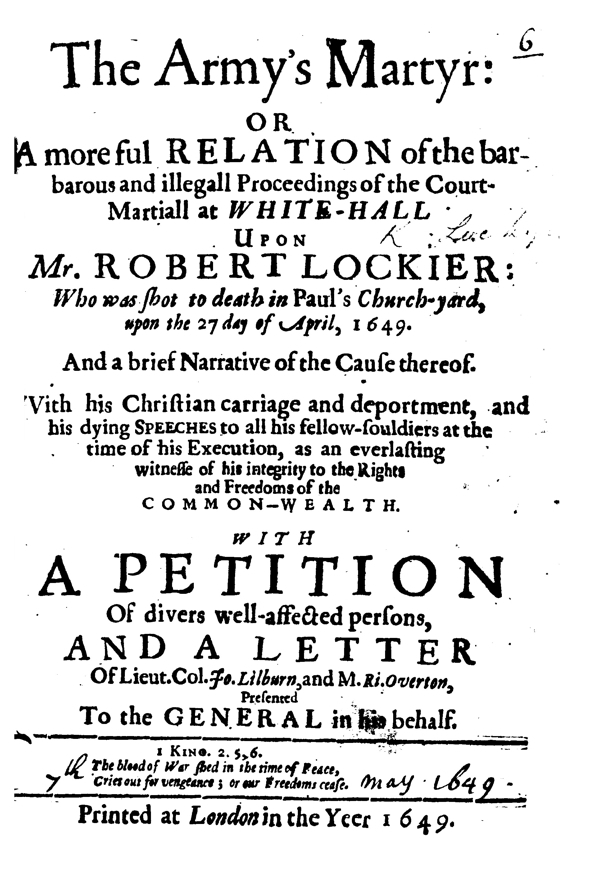

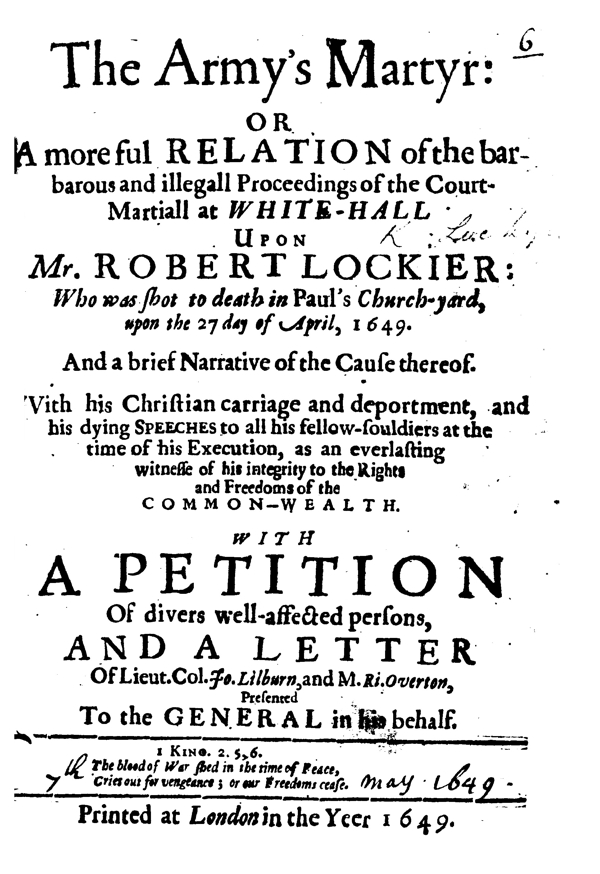

- [CORRECTED- 5 illegibles] T.192 (6.12) Robert Lockier, John Lilburne, and Richard Overton, The Army’s Martyr (4 May 1649).

- The Army’s Martyr

- To his Excellency Thomas Lord FAIRFAX Generall of the English Forces, The humble addresses of divers well affected persons, in behalfe of all those that are under restraint or censure of the Councel of War, or Law-Martiall

- The Copy of a Letter written to the Generall, from Lieut. Col. Jo. Lilburn and M. Rich. Overton, Arbitrary and Aristocratical prisoners in the Tower of London, the 27 of April 1649, in behalf of Mr. Robert Lockier

- The Postscript to the Reader

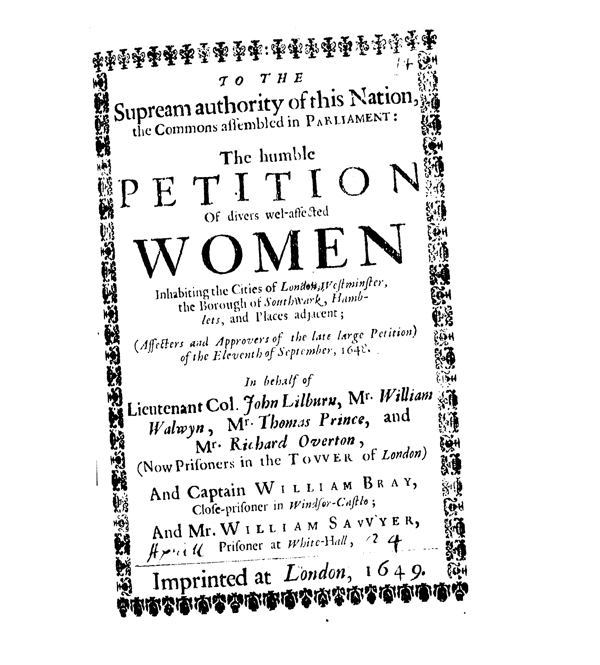

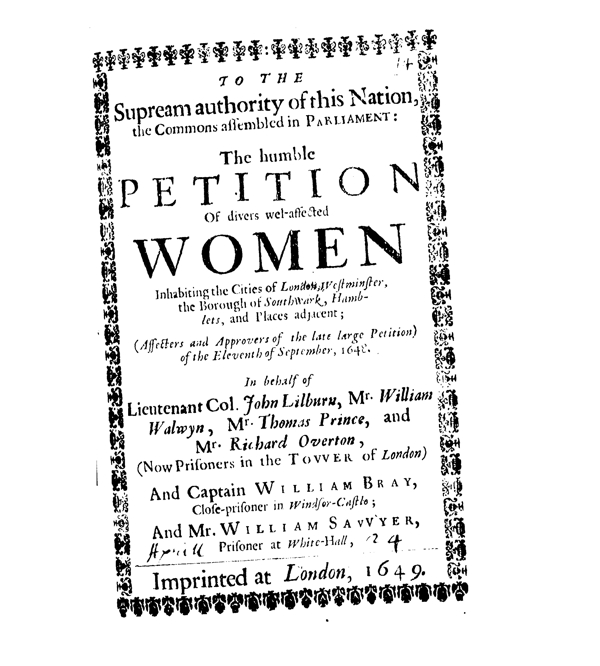

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.175 (6.27) Anon., The humble Petition of divers wel-affected Women (5 May, 1649).

- [UNCORRECTED - 69 illegibles] T.193 (9.40) Robert Bennet, King Charles Triall Justified (9 May, 1649).

- The sum of the Charge at the Sessions held at Trewroe Aprill 3. 1649. for the County of Cornwall.

- To the Religious and Honorable Sir Waller Knight, Commander in Chief of all the Western Forces and Garisons.

- [CORRECTED- 2 illegibles] T.194 ] (6.13) Oliver Cromwell, The Declaration of Lieutenant Generall Crumwel Concerning the Levellers (14 May 1649).

- The Declaration of Lieutenant Generall Crumwel Concerning the Levellers

- Humphrey Brooke, The Levellers new and ultimate proposals (28 May, 1649)

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.195 (6.14) [Humphrey Brooke], The Charity of Church-men (28 May 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.196 (6.15) William Walwyn, The Fountain of Slaunder Discovered (30 May 1649).

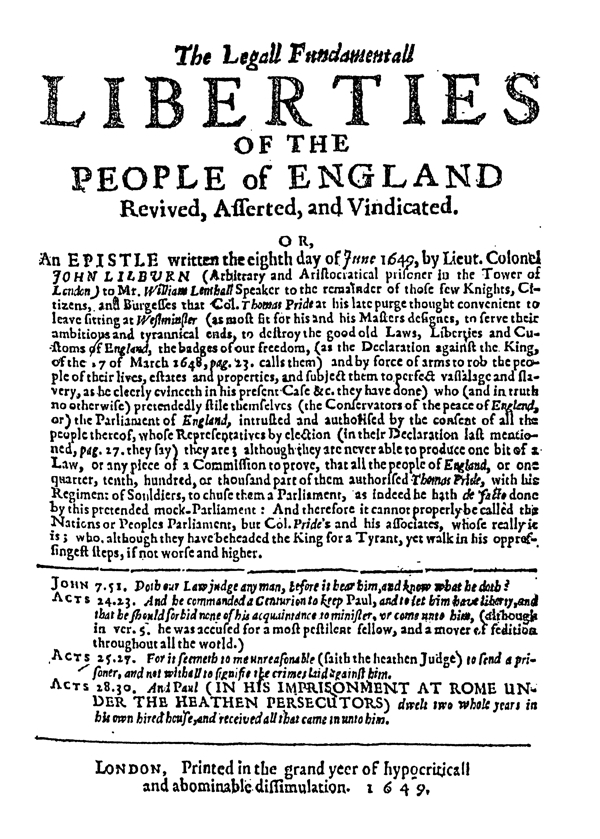

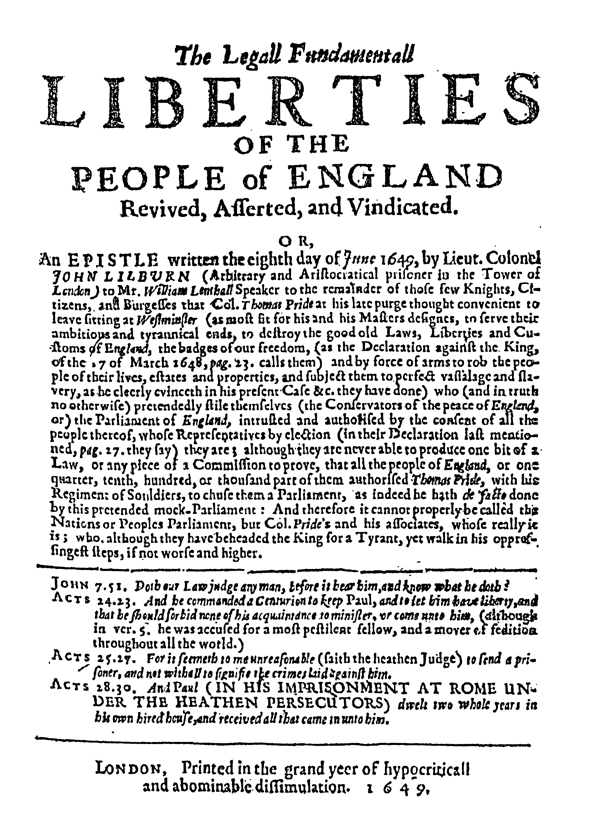

- [CORRECTED- 148 illegibles] T.197 (6.16) John Lilburne, The Legall Fundamentall Liberties of the People of England Revived, Asserted, and Vindicated (8 June 1649).

- Introduction

- The Plea it self

- (Other material)

- The Act Anno XVII Caroli Regis

- (other material)

- The printer to the Reader

- [CORRECTED - 23.04.18 - 114 illegibles] T.198 (9.41) John Warr, The Corruption and Deficiency of the Lawes of England (11 June, 1649).

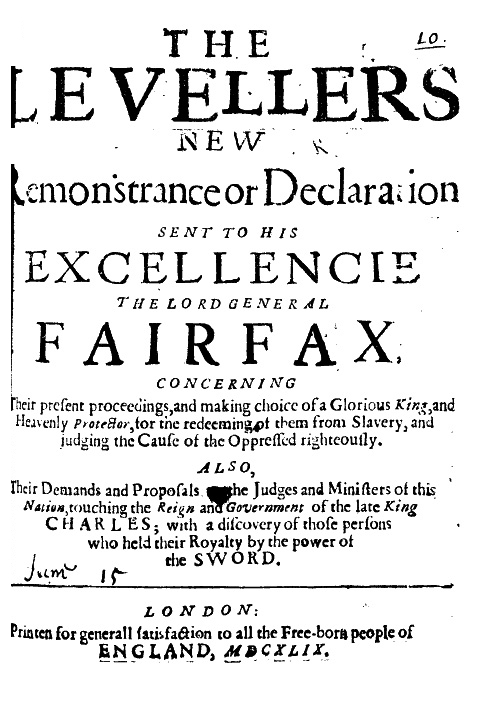

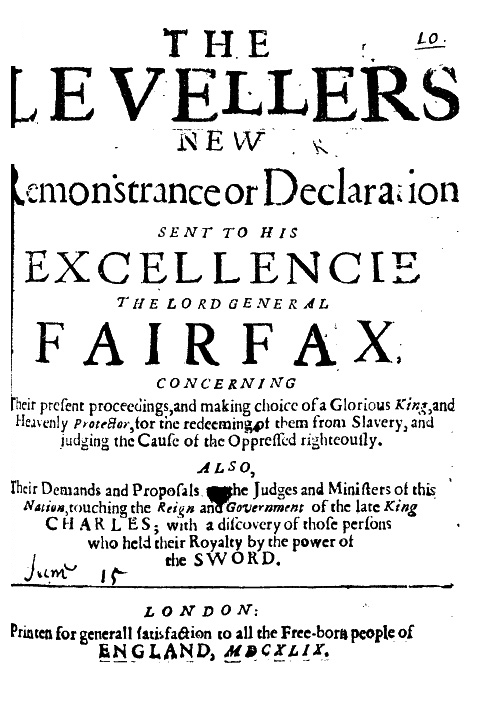

- [UNCORRECTED - 104 illegibles] T.199 (9.42) Anon., The Levellers New Remonstance (15 June, 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 2 illegibles] T.200 (6.17) Thomas Prince, The Silken Independents Snare Broken (20 June 1649).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.291 [1649.06.22] (M12) Anonymous, The Grand Case of Conscience stated about Submission to the new and present Power (22 June 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.201 (6.18) William Walwyn, Walwyns Just Defence (June/July 1649).

- Reasons Assigned

- Postscript

- [CORRECTED- 23 illegibles] T.202 (6.19) Richard Overton, Overton’s Defyance of the Act of Pardon (2 July 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 51 illegibles] T.203 (6.20) William Prynne, A Legall Vindication Of the Liberties of England (16 July 1649).

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.204 (6.21) Richard Overton, The Baiting of the Great Bull of Bashan (16 July 1649).

- [UNCORRECTED - 196 illegibles] T.205 (9.43) William Bray, Innocency and the Blood of the slain Souldiers, and People (17 July, 1649).

- A LETTER To an Eight yeers SPEAKER OF THE House of Commons

- Letter from Major Reynolds to go for Orders for quarters

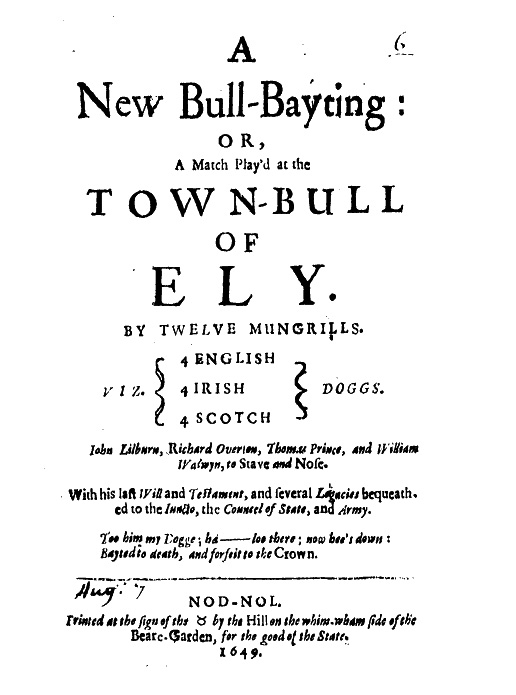

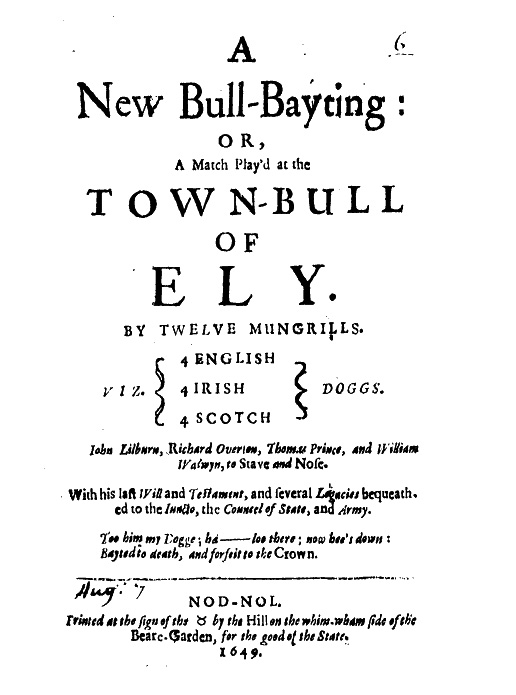

- [UNCORRECTED - 48 illegibles] T.206 (9.44) Richard Overton, A New Bull-Bayting: or, A Match Play’d at the Town-Bull of Ely (7 August, 1647).

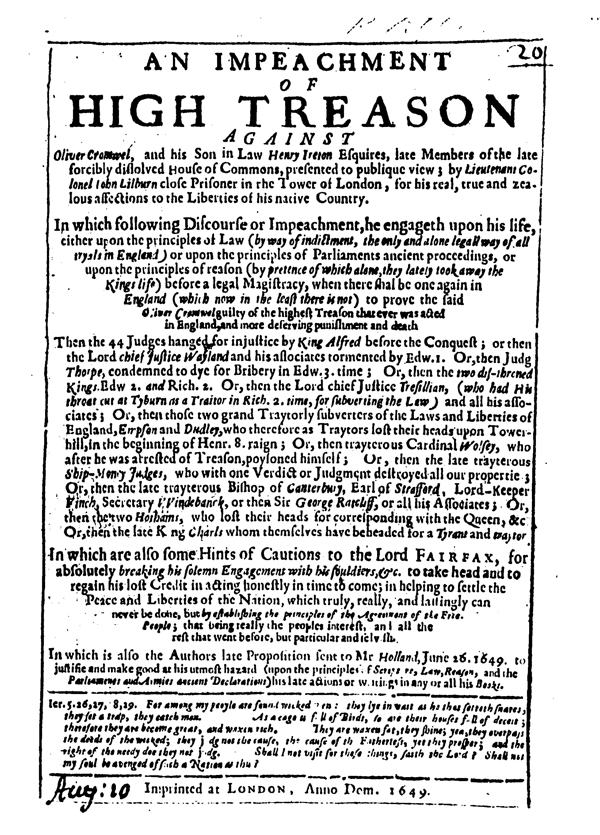

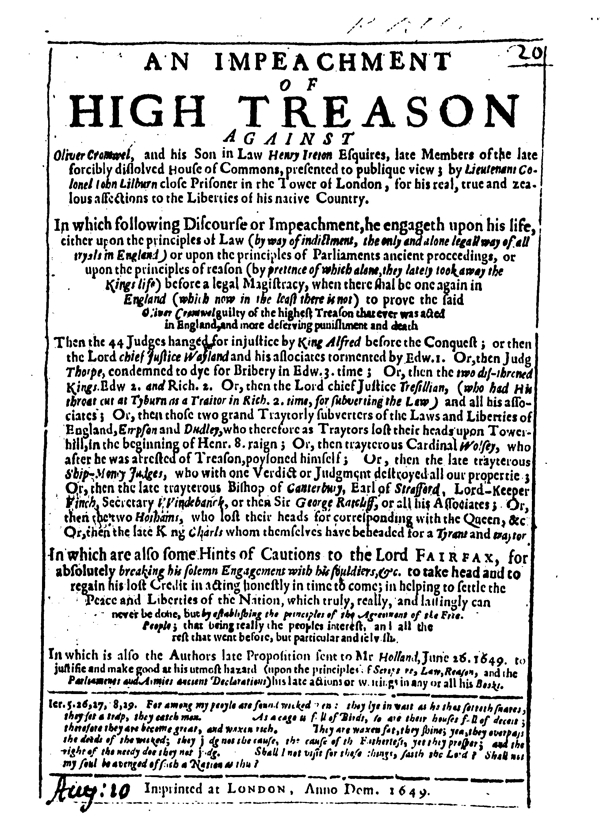

- [CORRECTED- 46 illegibles] T.207 (6.22) John Lilburne, An Impeachment of High Treason against Oliver Cromwel, and his Son in Law Henry Ireton Esquires (10 August 1649).

- The Author to the Courteous Reader.

- To all the Affectors and Approvers in England, of the London Petition of the eleventh of September, 1648

- TO His honored Friend, Mr. Cornelius Holland, These

- My Prayer

- Copy of Petition: To the Supream Authority of England, the Commons assembled in PARLIAMENT. The earnest Petition of many Free-people of this Nation ("THat the devouring fire of the Lords wrath")

- Sundry REASONS inducing Major ROBERT HUNTINGTON to lay down his Commission, Humbly presented to the Honourable Houses of Parliament, 2 August, 1648

- To the Honorable the chosen and betrusted Knights, Citizens, and Burgesses assembled in PARLIAMENT: The humble Petition of divers wel-affected Free-born people of England, inhabiting in and about East-Smithfield and Wapping, and other parts adjacent

- The CHARGE of the Commons of England, against CHARLES STUART King of England, Of high Treason, and other high Crimes, exhibited to the High Court of Justice, Saturday the 20 of January, 1648(49)

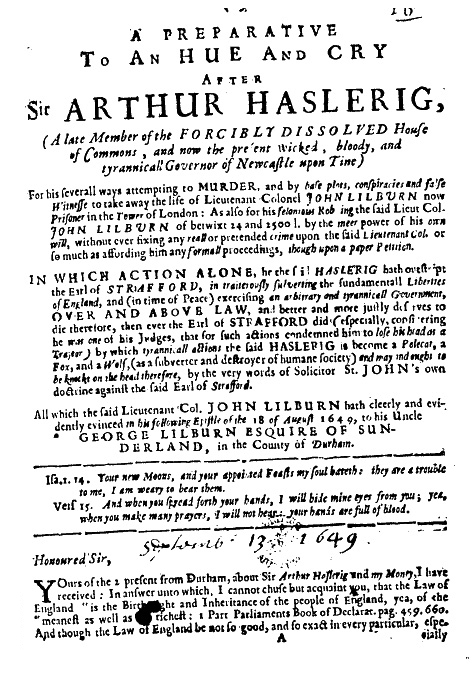

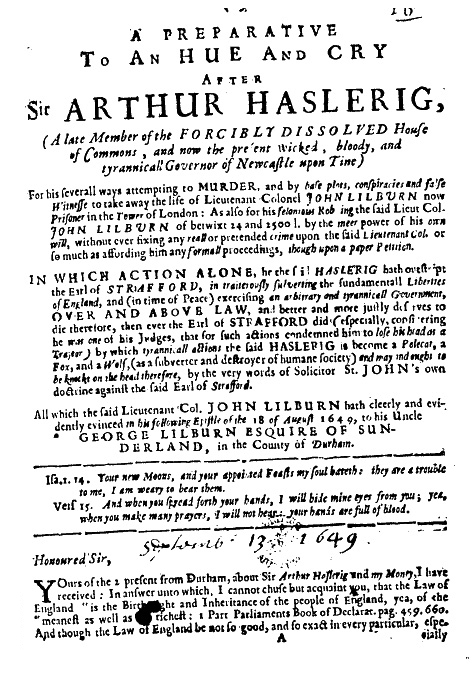

- [UNCORRECTED - 880 illegibles] T.208 (10.16) John Lilburne, A Preparative to an Hue and Cry (18 August, 1649).

- Letter to his uncle George Lilburn (18 Aug. 1649)

- Letters of Tho. Verney

- The Humble Remonstrance of Lilburn (4 Sept., 1648)

- An Ordinance of the Lords and Commons Assembled (18 April, 1638)

- Articles of High Treason

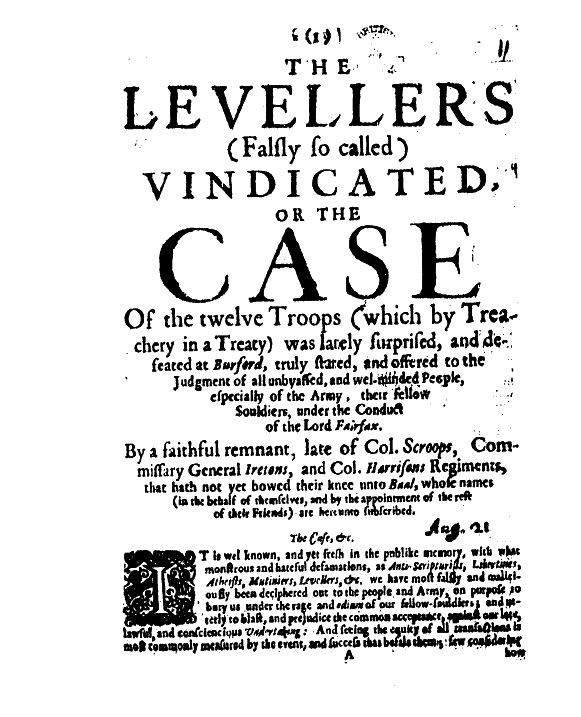

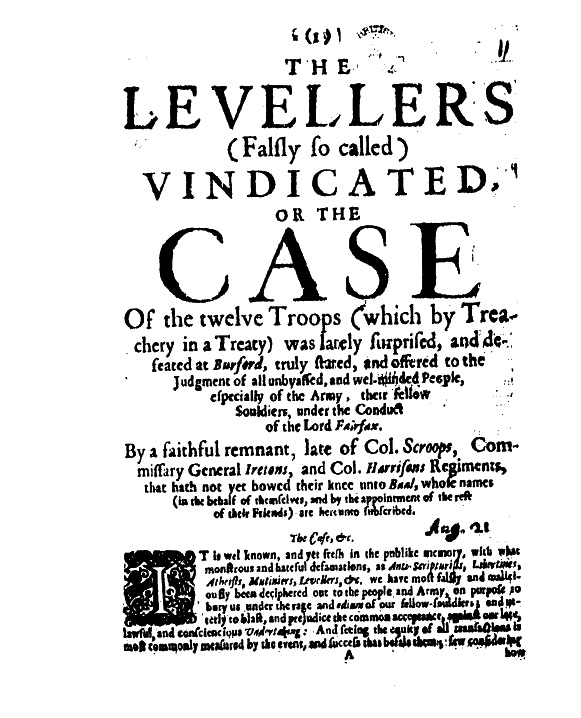

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.209 (6.23) Six Soldiers (John Wood, Robert Everard, Hugh Hurst, Humphrey Marston, William Hutchinson, James Carpe), The Levellers (falsely so called) Vindicated (20 August 1649).

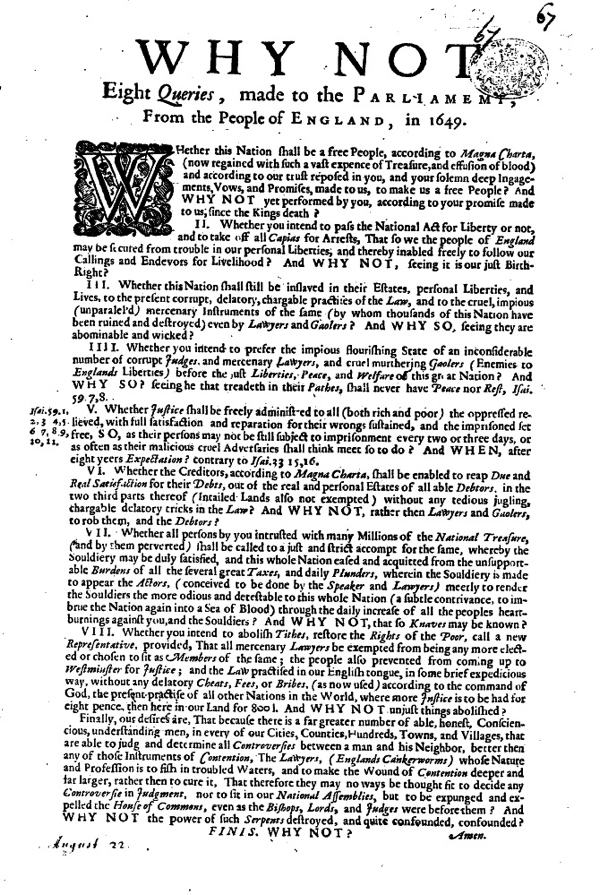

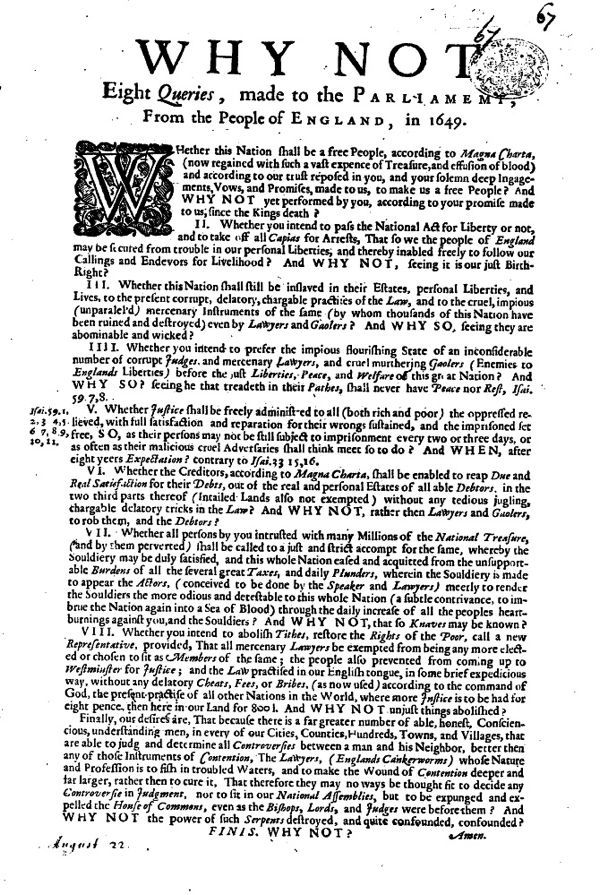

- [UNCORRECTED - 0 illegibles] T.210 (9.45) James Frieze, Why not? Eight queries made to the Parliament (22 August, 1649).

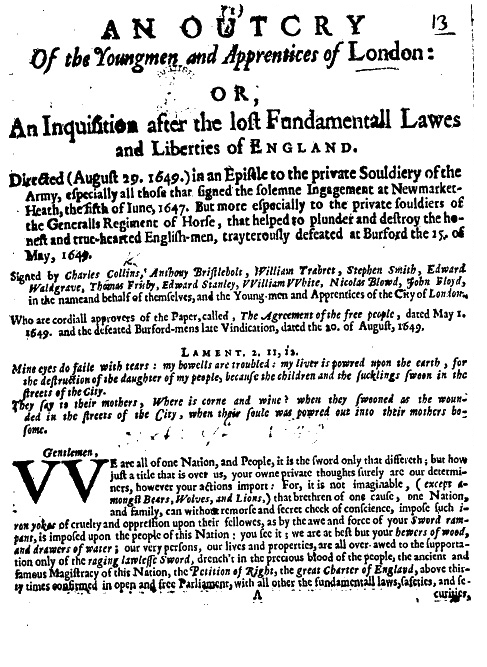

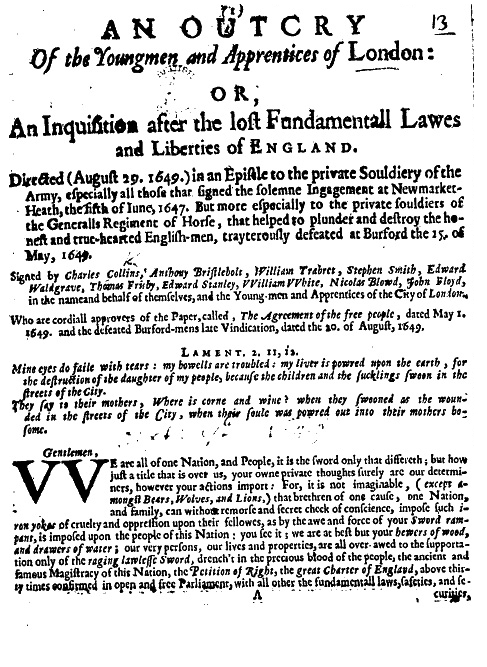

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.211 (6.24) [Signed by several but attributed to John Lilburne], An Outcry of the Youngmen and Apprentices of London (29 August 1649).

- Letter

- To the supreme Authority of this Nation, the Commons of England assembled in Parliament: The humble Petition of the oppressed of the County of Surrey, which have cast in their Mite into the Treasury of this Common-wealth

- [UNCORRECTED - 153 illegibles] T.212 (9.46) Gerrard Winstanley, A Watch-word to the City of London (10 September, 1649).

- [CORRECTED - 0 illegibles] T.213 (9.47) Anon., The Remonstrance of many Thousands of the Free-People of England (21 September, 1649).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.273 John Milton, Eikonoklastes (Oct., 1649).

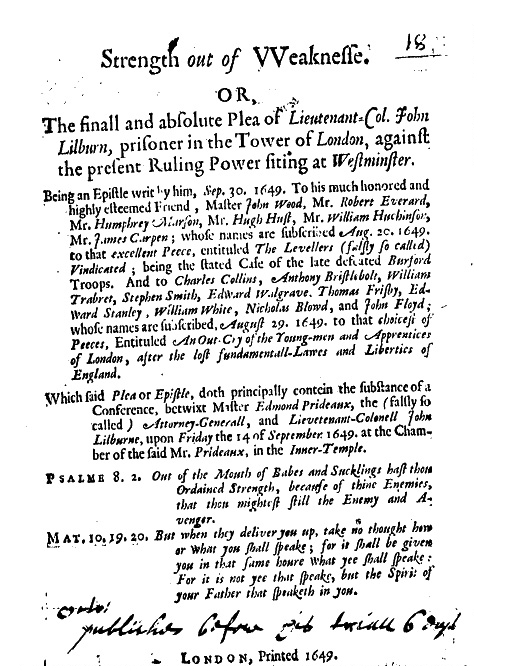

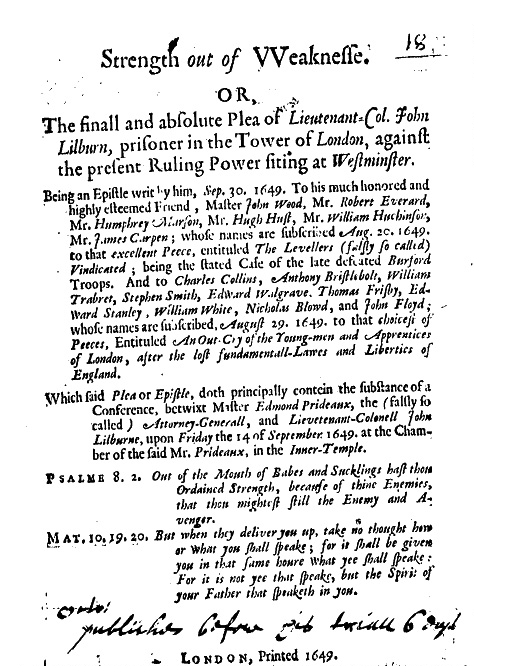

- [UNCORRECTED - 388 illegibles] T.214 (10.17) John Lilburne, Strength Out of Weaknesse (19 October, 1649).

- Letter to John Wood (30 Sept., 1649)

- For my honored Friend Col. Alexander Rigby (24 Aug., 1649)

- Postscript

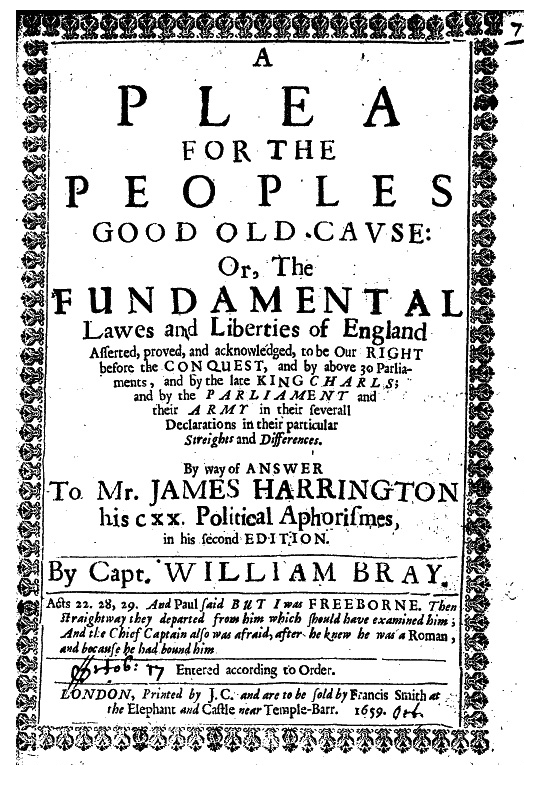

- [move from vol. 7??] [UNCORRECTED - 0 illegibles] T.256 (7.39) William Bray, A Plea for the Peoples Good Old Cause (2nd ed., 17 October, 1659; 1st ed. 24 Oct., 1649).

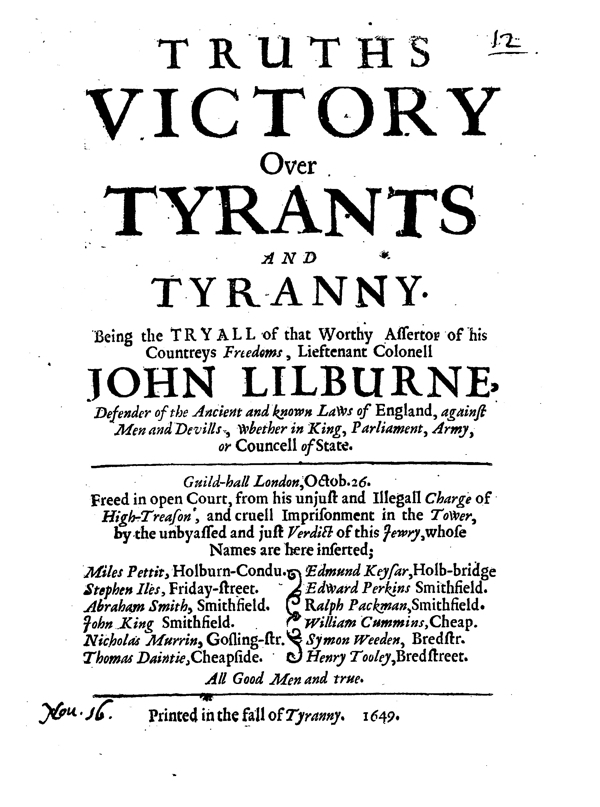

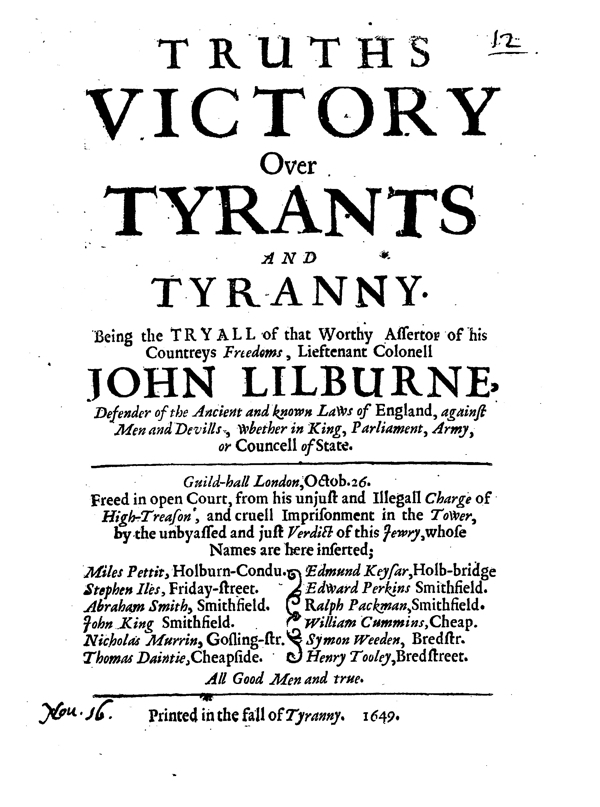

- [CORRECTED- 0 illegibles] T.215 (6.25) John Lilburne, Truths Victory over Tyrants and Tyranny (16 November 1649).

- Truths Victory over Tyrants and Tyranny

- A Copy of a Warrant, sent from the Councel of State, for the Releasement of Lievtenant Colonel Iohn Lilburne from his Imprisonment in the TOWER

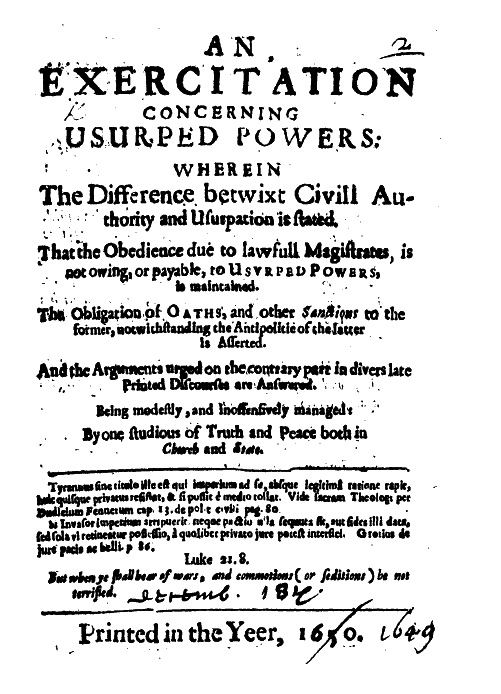

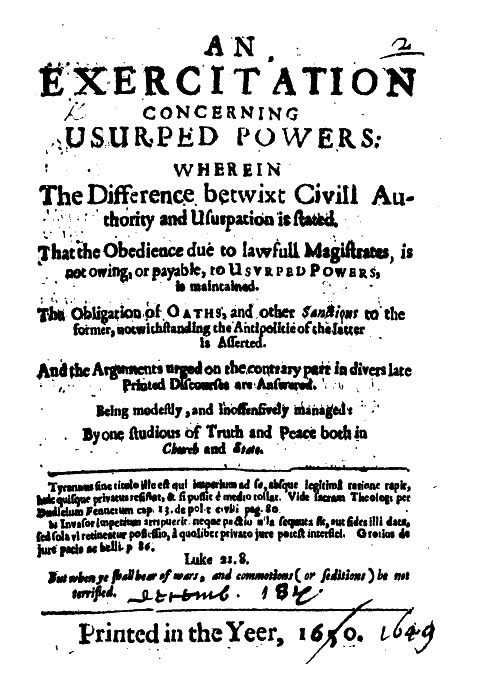

- [CORRECTED - 243 illegibles] T.216 (7.1) Richard Hollingworth,, An Exercitation concerning Usurped Powers (18 December, 1649/1650).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - NEED TO RECHECK] T.292 [1649.12.20] (M13) George Lawson, Conscience Puzzel’d About (20 Dec., 1649).

- Endnotes

Introductory Matter↩

[Insert here]:

- intro image and quote

- Publishing History

- Introduction to the Series

- Publishing and Biographical Infromation

- Key to the Naming and Numbering of the Tracts

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

- Further Reading and info

Key (revised 21 April 2016)↩

T.78 [1646.10.12] (3.18) Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646).

Tract number; sorting ID number based on date of publication or acquisition by Thomason; volume number and location in 1st edition; author; abbreviated title; approximate date of publication according to Thomason.

- T = The unique “Tract number” in our collection.

- When the month of publication is not known it is indicated thus, 1638.??, and the item is placed at the top of the list for that year.

- If the author is not known but authorship is commonly attributed by scholars, it is indicated thus, [Lilburne].

- Some tracts are well known and are sometimes referred to by another name, such as [“The Petition of March”].

- For jointly written documents the authoriship is attributed to "Several Hands".

- Anon. means anonymous

- some tracts are made up of several separate parts which are indicated as sub-headings in the ToC

- The dating of some Tracts is uncertain because the Old Calendar (O.S.) was still in use.

- (1.6) - this indicates that the tract was the sixth tract in the original vol. 1 of the collection.

- Tracts which have not yet been corrected are indicated [UNCORRECTED] and the illegible words are marked as &illegible;. Some tracts have hundreds of illegible words and characters.

- As they are corrected against the facsimile version we indicate it with the date [CORRECTED - 03.03.16]. Where the text cannot be deciphered it is marked [Editor: illegible word].

- After the corrections have been made to the XML we wil put the corrected version online in the main OLL collection (the “Titles” section).

- [elsewhere in OLL] the document can be found in another book elsewhere on the OLL website.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement↩

The texts are in the public domain.

This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Editorial Matter↩

[Insert here]:

- Editor’s Introduction to this volume

- Chronology of Key Events (common to all volumes)

Tracts from 1649 (Volume 6)

T.173 (9.35) Marchamont Nedham, The Great Feast at the Sheep-shearing of the City and Citizens (1649).↩

Editing History:- Illegibles corrected: HTML (24.04.2018)

- Illegibles corrected: XML (24.04.18)

- Introduction: date

- Draft online: date

Local JPEG TP Image

Bibliographical Information

ID NumberT.173 [1649. ??] (9.35) Marchamont Nedham, The Great Feast at the Sheep-shearing of the City and Citizens (1649).

Full titleMarchamont Nedham, The Great Feast at the Sheep-shearing of the City and Citizens, on the 7th. of Iune last: Consecrated for an Holy Thursday in Memorandum of St. Thomas, and St. Oliver; Solemnly holden at the Grocers Hall, London, 1649. To the Tone or Garb of the Counter Scuffle.

Printed in the Yeare, 1649.

c. 1649 (no month specified).

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationNot listed in TT.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

The great Feast, at the Sheep-shearing of the City and Citizens, on Thursday the 7. of Iune last.

MY Reader must not here suppose

That I will waste good Verse or Prose

On Fairfax face, or Cromwels nose,

Or Atkins savoury breech;

Nor Skippen (that almighty Major)

Or Ireton (Commissary Rager)

Nor will I write (I’le lay a wager)

Like Pembroks Learned speech.

The famous Acts of Noble Hero’s,

Great Englands brave Renowned Nero’s,

And all their Stout Biberius Mero’s

Behold their entertainment;

And if with patience you will read,

(If God be pleas’d to send good speed)

’Tis thought the fates are all agreed

To further their araignment.

Now for the Feast, I hold it fit,

(Although my selfe had not a bit)

That something of it should be writ

For after imitation;

Therefore I’le shew the cause wherefore

This Feast was eate, payd for, and more,

And not one penny set oth’ score,

(A worthy commendation.)

These costs were spent to cannonize

Those mighty mortall Dieties,

Then stroak your beards, and wipe your eyes

If you’l behold their splendor;

Then (Ecce signum) these are they

Who layd King Charles as cold as clay,

And by that Act most fit they may

Be call’d no Faiths Defendor.

These Worthies have fought for the Cause,

For our Religion, Lives, and Laws,

And set us free from Tyrants claws,

Now truth and right beares sway:

All Taxes now are layd aside,

Plenty of all things, far and wide

Folkes may in peace, both go or ride,

The cleane contrary way.

These, these are they, whose Noble Actions

Purg’d Church and State from putrifactions,

Cur’d our distempers and distractions.

And set us all in quiet:

And have they done for us all this,

As th’ only Authors of our blisse,

We held it therefore not amisse

To give them some good diet:

True Citizens, are Cities sons,

Whose wit and coine, in plenty runs,

Their hogsheads empty many tuns,

They are such kinde of folks;

For all our troubles they are grac’d,

And in the formost rancks are plac’d,

And all true Pallats them do taste

Like Eggs that have no yolks.

This Army, and this Parliament,

Hath been th’ Appointed instrument

To save them all from detriment

By cowing of their courage.

They kisse the rod, and love the threaters,

They are enamourd of their cheaters,

And humbly beg them to be eaters

Of Venison, Wine, and Burrage.

But for this feasts great preparation,

And how ’twas kept with Acclamation,

I will not wrong your expectation

With more delayes or fables.

They all prepar’d to cleanse their sinne

By Owens Preach, and Tom Goodwin,

In Christ Church which hath never been

Like other Churches stables.

But Christ Church was for other beasts

Then Horses, or horn wanting creasts,

Though Bucks or Stagges be at the feasts,

Yet sure there were not any.

There might be Athiests there perhaps

(Who fear not Heavens great thunder claps)

Nor think hells all devouring chaps

Will swallow half so many.

Yet at these Preachments and sweet prayers

There were Beasts, Tygers, Wolves and Beares,

And greedy dogs with prick’d up eares,

But not one Royall Lion:

Some asses and some crafty Foxes,

Who hide stolne treasure in their boxes,

And some that plea’d their dells and Doxeys

With musick like Arion.

The Preachers very zealously

Mock’d God (with thanks for victory,

And Popham came triumphantly

Well beaten from Kinsale.

But after three houres long digressings,

The Levites salved all Trangressings,

And gave them Independent blessings

By whole sale and Retale.

The Pomp of these most Pompous sinners

From Heavenly food to Earthly dinners,

Gaz’d on by Oyster wives and Spinners,

And Porters in abowndance.

Fine silken fools, brave golden gulls,

Some modest maids, some shamelesse Trulls,

And Trumpeters neere split their sculls

With noise would make a Hownd dance.

The Marshall mounted on his Steed

(With care Prudentiall, and good heed)

Usher’d the Heard where they might feed,

Of people made two hedges:

Next whom the Grocers Livery men,

The Common Councell followed then,

Which all appeared (to my ken)

Like Beetles, Blocks, and Wedges.

The Officers and Squires before,

(With needlesse creatures many more)

And one a Cap of Maintenance wore,

And in his hand a sword,

Which never man in anger drew;

For had they drawn it just and true,

Then never had the damned crue

Destroy’d our Soveraigne Lord.

Next that the Mayor of London rode,

His Horse and He had each their Load

Whose Lordships both, gave many a nod

To people as he passes.

His Scarlet gown his back did beare,

And ’bout his neck he then did weare,

A bunch of Jewells rich and deare,

Hang’d in a collar of Asses.

The City musick sweetly fidled,

And Bells (in Changes) rung and ridled,

Whilst on their Palfries they down didled

Through Cheapsides famous street.

I tell you that the like was n’er

Since Williams raigne (the Conquerere)

And ne’r will be the like I feare,

’Tis better fortune greet.

Then follow’d Englands Pompey (Tom)

And his Commander (Well com Crom)

Whose sights the people (thither com)

With foure houres stay expected,

But they with th’ Speaker and the Mace,

Disdain’d the multitude to grace

With one good glance of one good face.

Which made them disaffected.

For some said Toms was black and blue,

And Nols was of a crimson hue,

And each of them lookt like a Jew

That murdered had their Christ.

For sure they can have no excuse

For their inhumane base abuse.

Their Kings and good mens blood to sluce,

The Dee’l them all entis’d.

Thus they in triumph past along

Through deere Cheapeside, and all the throng,

Whilst thousand curses was the song

Which blest them as they went;

At Grocers Hall, they grocely fed,

With which their paunches out were spread,

Whilst thousands starve for want of bread,

Let’s thanke the Parliament.

Neere forty Bucks, these Holy Ones

Devour’d, and left the dogs the bones,

And Musick grac’d with Tunes and Tones,

This Bacchanalian Feast:

And after that, a Banquet came

Of sweet meates of rare forme and frame,

Of Castles, Towres, and Forts of Fame,

More then can be exprest.

But one thing now to minde I call,

They lackt a Marchpane like White-Hall,

’Fore which a Scaffold square and tall,

And on it a good King;

And there his head to be off chop’d,

And all his Branches bravely lop’d,

How three great Kingdomes blisse was crop’d;

This had been a fine thing.

Thus with the Ordnance thundring rore,

My mute is mute, I must give ore,

Whilst Englands woes good men deplore.

Whilst Tyrants feast with joy;

But I desire, that every one

Would humbly pray to God alone

To set the second Charles on’s Throne,

And all our Griefes destroy.

FINIS.

T.176 (10.15) [Richard Overton], The Moderate (December 1648 - January 1649).↩

Editing History:- Illegibles corrected: HTML (date)

- Illegibles corrected: XML (date)

- Introduction: date

- Draft online: date

OLL Thumbs TP Image

Local JPEG TP Image

Bibliographical Information

ID NumberT.176 [1649.01] (10.15) [Richard Overton], The Moderate (December 1648 - January 1649).

- no. 21 (Nov. 28 to Dec. 5, 1648) to no. 33 (Feb. 20-27, 1649)

The Moderate: Impartially communicating Martial Affaires to the Kingdome of England.

Estimated date of publicationNo. 21 From Tuesday Novemb. 28. to Tuesday December 5. 1648; to No. 33 From Tuesday February 20. to Tuesday February 27. 1649.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT2, pp. 404–5; E. 475–477, 536–540; 541–543, 545.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

Text goes here

The Moderate: Impartially communicating Martial Affaires to the Kingdom of ENGLAND.

From Tuesday Novemb. 28. to Tuesday December 5. 1648.

I Finde, amongst earthly comforts and blessings, that a good Prince Is Marshalled in the Van, and takes priority of all the rest, being clothed with Honour, Love, and Soveraign Splendor; and an evill Prince in the Reer, as the heavyest of all Plagues, and greatest of all Judgements upon earth, bringing desolation, and generall destruction whereever he raigneth, and therefore as the whole Body is of more authority then the only Head, and may cure the Head if it be out of tune; so may the weal-publike cure or purge their Heads, if they insect the rest, seeing that a body Civill may have divers Heads, and is not bound ever to one, as a Body naturall is; which body naturall, if it had the same ability, that when it had an aking, or sickly head, it could cut it off, and take another, I doubt not but it would so do, and that all men would confesse it had authority sufficient, and reason to do the same, rather then all the other parts should perish, or live in pain, or continuall torment: But much more clear it is, That all Common wealths have in all Ages lawfully chastised their lawfull Princes, though never so lawfully descended (as the people now say) or otherwise lawfully put in possession of their Crown: And (which is most remarkable) this hath alwayes, or for the most part fallen out most commodious and profitable, for those Common wealths have been crowned with blessings from heaven by the good successe, and successors that ensued hereof.

The points held forth are high, and the Reader expects proof hereof, which I shall do, with as much brevity as may be, and first I shall prove it by Scripture: I finde in 1 Kings 31. and 4 Kings 21 & 44. That two wicked Kings, Saul and Ammon (though both of them were lawfully placed in that dignity) were lawfully deprived, and put to death by the people; and did not God afterwards bring in David and Josias in their rooms, who were the two most excellent Princes that ever that Nation, or any other (I think) have had to govern them.

And first, King Saul, though he were elected by God to that Royall Throne, yet was he slain by the Philistimes, by Gods order, as it was foretold him, for his disobedience, and not fulfilling the Law, and limits prescribed unto him.

Ammon was a lawfull King also, and that by naturall descent and succession, for he was son and heir to King Manastes, whom he succeeded, and yet was he lawfully slain by his own people, Quia non ambulavit in via Domini, because he walked not in the wayes prescribed unto him by God. And for those two good Kings that succeeded them, we reade Jasias did that which was right in the fight of God, neither did he decline unto the right or the lese: And David likewise we finde to be a man after Gods own heart.

And now if we will leave the Hebrews, and return to the Romans, we shall finde divers things notable in that State also, to the people thereof; For before &illegible; their first King, having by little and little declined into Tyrannie, he was stain, and cut in pieces by the Senate, Hallib. 1. and in his place was chosen Numa Pompulius, the notablest King that ever they had, who prescribed all their manner of Sacrifices, imitating therein and in divers other points, the Rites and Ceremonies of the &illegible; he began also the building of their Capitol, adding the two moneths of January and February to the year and other notable things for that Common-wealth. Again, when Tarquinim the proud, their seventh and last King, was expelled by the Senate for his cruell Government, and the whole manner of Government changed: We see the &illegible; was prosperous, so that only no hurt came thereby to the Common-wealth, but exceeding much good; their government and increase of the Empire was prosperous, under their &illegible; for many years, in such sort, that whereas at the end of their Kings Government they had but fifteen miles teritory without their City, it is known, that when their Consuls government ended, and was changed by Julius &illegible; their territory reached near fifteen thousand miles in compasse, for that they had not only all Europe under their Dominion, but the principall parts of all Asia, and Africa, so as this chastisement, so iustly laid upon their Kings, was profitable, and beneficiall to their Common-wealth.

When Julius &illegible; upon particular ambition, had broken all Law, both Humane, and Divine, and taken all Government into his hands alone he was, in revenge hereof, stain by Senators in the Senate house, and &illegible; Augustus preferred in his room, who proved afterwards the most famous Emperour that ever was.

The like may be said of the Noble Ranke of the five excellent good Emperours; wit. Nervs, Trajun, Adrlan, &illegible; &illegible; and Marcus Aurelius, that insued in the Empire by the just death of cruell Domitian, Europ. in vitz Casa.

The two famous changes that have been made of the royall Line in France; The first from the Race of Farmond and &illegible; to the Line of Pepin; And the second from the Race of Pepin againe, to the Line of Huge Capetus, that endureth unto this day.

Step over now the Pireny Mountaines, and look into Spaine, and there you shall finde a lawfull King, named &illegible; &illegible; puld downe and deprived, both he and his posterity, in the fourth Councell Nationall of Taledo, and one &illegible; confirmed in his place. Likewise one Don Alanso, the eleventh of that name, for his evill government and tyranny was deposed by his Kingdome.

What should I name here the deposition made of Princes in our dayes by other Common-wealths, as in Polonis, of Henry the third, that was King of France, was deprived of his Crowne in Polonia, by publique Act of Parliament. Or the deprivation of Henry King of Suet a, who being lawfull successour, and in possession, after his Father &illegible; was puld downe by that Common wealth, and deprived, and his brother made King in his place; and this was allowed by all the Princes of Germany neere about that Realme, who say, the reasonable causes which that Common-wealth had to proceed as it did. But it will be best to end this Narration, with examples out of England it selfe, and that since the conquest, as King Edwin, and others; neither shall I stand much upon the example of King Iohn, After whose deposition the good King Henry the third was admitted; and what thinke you of Edward the second, who was deposed also by Act of Parliament, holden at London Auno 1326. and his body adjudged to perpetuall prison, and Edward his Sonne chosen in this place, for which he thankes them heartily, given them many thanks, and with many teares acknowledged the justnesse of his being degraded, his name of King was taken from him, and hee appointed to be called Edward of &illegible; from that houre forward, and then his Crowne and &illegible; were taken away, and the Steward of his house brake the staff of his Office in his presence, and discharged his servants of their attendance, and all other people of their obedience or allegiance towards him; and towards his maintenance, he had only 100 markes a yeare allowed him; and then delivered into the hands of Keepers, who led him prisoner to severall places, using him with extreame indignity in the way, untill at last they took away his life from him; and did not God blesse the people for executing judgment on this King, by giving them Edward the third after him? And was not Richard the second (who suffered himself to be abused and misled by evill Counsellors, to the great hurt and &illegible; of the Realme) deposed by Act of Parliament, holden in London &illegible; 1399. and condemned to perpetuall prison, in the Castle of Pontefract, where he was soon after put to death also: And was not King Henry the sixth, after he had raigned almost 40 yeares, Imprisoned and put to death, together with his son the Prince of Wales, by E. 4. of the house of York, and the same was confirmed by the Commons, and especially by the people of London, and afterwards also by publike act of Parliament for that he suffered himselfe to be over ruled by the Queene his wife, and had Articles of Agreement made by the Parliament, between him and the Duke of York; And these may serve for proofe, that lawfull Princes have oftentimes by their Common-wealths been lawfully deposed for mis-government. And that God hath allowed, and assisted the same with good successe unto the Weale publique.

The Cosackes, Instead of pursuing their victorie, as it was very easie to doe, considering how numerous they were, and withall the confusion that was all over the Kingdome of Poland, happening by reason of their late overthrow; neverthelesse, they are gone to their old Quariers, where they only make mercy with the Plate, and other booty lately gained in the late fight; yet it is said, they doe not intend to give over thus, having lately made an Agreement with the Tartars, whom they promise to assist, and help to shake off the Turkish yoake, upon condition, the Tartars shall likewise give them all assistance against the Kingdome of Poland. In the meane time, it hath been resolved upon, for the Election of a new &illegible; in the Diet now adembled, and that to be the 4. of November next, but by reason that both brothers doe lay claims to the Crowne, it seemes that the younger, who in the beginning had a very strong party, but since much weakned, therefore maketh a demarre in the Election, seeing it is not like to goe on his side. Yesterday Prince &illegible; (who is still called here by the name of King of Sweden) sent soure Embassadours to the Diet, where the Bishop of Samogiria being to speak for the rest, demanded the Crowne for this Prince, to whom the Archbishop of Guesuer answered, that he would take advice with the rest of the Assembly; and besides, made a long speech in the commendation of this Prince, and how much obliged the State was unto the Kings, his Progenitors. Some few dayes before, the Prince of &illegible; sent to demand the Crowne for his second senne, promising, in case it were granted, to make warre against their enemies the space of three yeares, at his own cost and charges.

While that the Senateurs assembled at Warsoviæ, about the Election of a new King of Poland, The forces of that Kingdome, who being now joyned together, making a very considerable Army, are marching in a full body to oppose the Cosackes, who as it is reported, are divided into three distinct Armies; The first being gone into &illegible; The second towards Warsoviæ, and &illegible; and the third remaineth about Lenberg; Although it is said, that having stormed the place, they had a great repulse, with the losse of 1200. of their men, whereupon the report goeth, they march to &illegible; where the Prince of &illegible; hath retired himselfe with 6000. men, for the defence of that place. There is a report, that Prince &illegible; doth cause to be made a high way through a Wood, wide enough to passe eight waggons a brest; this to be a passage for his forces that he intends to bring into Poland, in case he be denied his request concerning the Crowne, intending to joyne with the Cosackes, who with their horse make daily intoades, and much annoy the Countrey, insomuch that the Countreymen are forced for their security to joyn with the Gen. &illegible; chiefe Commander of the Cosackest. neverthelesse it is reported, that they are about to send Commissioners to Warsoviæ, to treat about an accommodation.

The 8. instant the Te &illegible; was song here, and our Ordnance discharged three times, for joy of the happy conclusion of a generall Peace in Germany. The King of Denmarke, after he had received the homage of the Towne of Melderse, in &illegible; went two dayes after to &illegible; where he was royally entertained by the Duke of Holstela, and so from thence returned to Koppanbagen, to be present at the funerals of his late deceased father, and so to be crowned the 6th. of the next moneth; And by reason that our Magistrates are invited to the Solemnity, therefore they have deputed one Burgomaster, one Sindye, and a Senatour to goe in their name to Koppanbagen, and carrie along with them such presents as are usuall; viz. One for his Majesty, The other for the Queen his wife, both being esteemed to the value of 8000. Rixdollars.

The 12. instant, General &illegible; with the Major Generals, Dougles, Horne, and Linden; the Count Palatin Philip, sonne to Count Palatin Frederick, the Palatin Lewis of Suitzbach, the Palatin Adolphus John, brother to the Swedes Generalissimo, and some other Officers of that Army came to this City, where the Magistrate sent them the same day, one waggon laden with wine, and two others with first, as is accustomed in the great Cities of Germany to be done, unto persons of that ranke. The 13. they viewed our Magazines, and General &illegible; did order the head Quarter of his Army to be at &illegible; a league from this City. The 14. they remored from thence, and went to Rikersdoif, one league and a halfe from this, place, towards the Palatinate; But yesterday the Army having turned back, most of them passed by us, and went to quarter at Grudlack, which is towards &illegible; about the same distance from us. Our Magistrate having sent them good store of bread and beer, and like provisions for their better subsistence. It is reported that a Diet is to be kept at Eamberg, to conclude concerning the Winter Quarters for the Swedish Army, who are resolved to take them in &illegible; till such time as there is a totall and reall execution of the Articles of the Peace lately agreed upon; and withall, they to be satisfied wholly, and have those summes of money paid that they are to receive, before they depart the Countrey.

The French Army, after they had taken Wisterstad, advanced as far as Britten, but are since drawne into their garrisons, upon the publishing of a Peace in Gaminie.

The suspension of armes on both sides, as it was agreed upon by the peace of Germany, being published, the Prince Palatine, Generalissimo of the Swedish Armies, is withdrawne from about Prague, towards Braudeis, Methick, and &illegible; there being left only in the lesser Towne, and the Castle, Lieutenant Generall &illegible; and Colonell &illegible; with 3000 foot souldiers and some Troops of horse, who are not to commit any act of hostility, by reason of this suspention of Armes, which begins to be observed.

The Lieutenant Generall Geis, who is Commander in chief of the &illegible; forces, hath part of his Army quartered at Geeven in this Diocesse, and from thence are to march further towards &illegible; and &illegible;

The Marquis Capponi, sent from the great Duke of Florence, to D. &illegible; de Austria is here, returned from Messine. Sir Glonettine &illegible; hath carried thither four galleys, intending to make new levies of men, which afterwards wil be convoyed into Spaint; Some companies of high dutch souldiers, that were about this City, have been sent into their winter quarters, in severall parts of this kingdome, chiefly in the Provinces of Ottrante Bari, Principality of Citra, and County of Malisa; A part of them had been commanded into the lands belonging to Count Di Conversane, but upon notice given to our Vice King, that he was still in Armes, with a full resolution to oppose their designes, therefore they have not proceeded any further, but are &illegible; to quarter elsewhere, The Count de Ovilde of the family of the Orsinie, hath been put in prison here, being arrested by a command from Count de &illegible; our Vice King.

The day of All Saints was held in the Colledge of Cardinals wherein the Cardinall de la Cueva said Masse, and the Cardinalls Giustiniars, and Franciotto the two daies following, the Pope not being there none of them dayes, being as yet sick of the &illegible; The Duke de Collepietro, who retired hither from Naples, to avoid the mischiefe which he might have received from the Spanish party there, was killed with severall shoes of fireloks, as he was passing through the place, called Sancta Mariamajor, this was done by the Bandiri, who are quartered within the Vineyard of P. &illegible; whom the Spaniards put in hopes to have the principality of Salerna bestowed upon him, as a gift from his Catholick Maiestie. But the Duke de Matalone, a Neapolitane, who was returning thither in a ship, which attended for him at the mouth of this river, going to imbarke himselfe with his followers; divers tradsmen, unto whom he was indebted, repaired thither, to demand of him their monies, and among others, a Tailot did speak so roughly, that the Duke growing in a passion, gave command to his men to cudgell him, and having so done, to throw him out of the window, which was effected; presently the Duke flieth from thence, and gers into one of the Jesuits houses, where the Governour of this City, seut many Officers to apprehend him, which being not able to do, they have seized upon al his goods, and follow the law so hard against him, that they have arrested most part of his servants, and set a strong guard in his Palace; but yet it is thought that the Prince Ludovisio will easily take up the businesse. The lands of the Duke of Parnia, which are upon the Popes deminions, are put to an outery, by a Decree from the Apostolick Chamber, for the payment of those debts which the Pope pretends due unto him by the said Duke, but as yet none proffer to buy, being fearfull to lose their moneys; in the meane time some forces have been sent towards Castro, as if there were an intent to besiege it, but it is very unlikely, in regard there is already a strong gartison in the Towne, besides 1000. foor, and a Companie of Dragoones the Duke hath lately sent thither for their better security.

The last Letters come from Candia, do certifie us, that the Turks having received some new supplies by a Grecian Commander, did thereupon give a furious assault upon the chief City of that Kingdom, but were repulsed from it with great losse. The 14 of September five hundred of their musquetiers did possesse themselves of one of the breaches of the wall, and from thence they were likewise beaten off, as also in their next storming of the Town, where they were beaten off with the losse of three hundred men; whereupon they being resolved to fall on more sicretly, did fall a storming about the Gate, called de Gicsu; but Generalissimo &illegible; who foresaw their design, had made that place so strong, that the Turks upon their approach were so well received by his men, that they were beaten back as formerly, but with a far greater losse, which put the Army into such a confusion, that immediately they withdrew further off, even two miles from the City, where was their old Quarter, which hath caused great joy to this State; as also the news lately come from Constantinople by the way of Vienn, certifying, that the divisions and differences increase more and more in the Turks Court, between the Spahis and the &illegible; the first reproaching the other with the death of the late great. Turk, and endeavoring to set upon the Throne one of his kindred in stead of Sultan Achmet. Two Galleys are ready to set out from hence to go for Dalmatia with moneys and Ammunition, the better to enable our forces to oppose the Turks, who make inroads as far as Zara. The Generall Foscole, who is Commander in chief in these parts, is gathering our Army together being in all about twelve thousand strong, that so he may send them to their winter quarters, only the Morlakes that intend not to leave the field, &illegible; a new occasion given them by the Turks, that provokes them to seek for revenge, the Turks having lately slain 100 of them in cold blood within their own doors, whereupon they have vowed to be revenged thereof at what condition soever it be. This State, for to help descay the charges they are yearly at by continuance of the Wars, do go on in the railing of the eight hundred thousand Ducloets whereunto the countrey is taxed since within these three years, and moreover have Ordered that a Galleasse be made ready with speed, and two Galleys.

The 7 Instant, the Marquis de &illegible; our Governour, returned from Lodi to this City; there are also come hither all the chief Officers of our Army, only two excepted, viz. D. Vincenzo &illegible; zague Generall of the horse, who is &illegible; &illegible; Novo &illegible; Scrivit; and D. Vincenzo Manzuri, Generall of the Artillery, who is gone else where; D. Diego de &illegible; being made Governour of Cremona in his stead. This Governour having sent most part of his horse towards Monteserrat under the command of D. Gioseppe de &illegible; Lieutenant Generall of the Neapolian forces, and of Dom &illegible; &illegible; Commissary Generall of our Armie, and there are to continue untill they receive orders for their winter quarters, upon advice received, that the Imperiall Princesse, who is betrothed to the King of Spaine, and &illegible; future &illegible; was to be in these parts shortly; therefore the Royal Chamber of this City hath named three to go as Deputies, to attend upon our frontiers, for Her Highnesses comming, besides is Citizens, that goe in the name of this Cities; the generall Exchange of prisoners being done, there is returned hither the Lieutenant Generall of the horse Tretty, and Major Generall &illegible; with many others, that are high Officers.

The 14 instant D. Charles Roncal, chief commander of the garrison at Mortars, was drawn, hanged, and quartered, for that he had endeavoured to betray the place, by holding intelligence with the Enemy, which was discovered by his own Lieutenant, who was his chief accoser, and avowed that he would have made him a chief Agent in the businesse; the Inhabitants of that place likewise pressing very hard against him to take away his life; and one of them to shew his thankfulnesse unto God for the same, hath bestowed a gift upon our great Church, esteemed to be worth 1100 Ducatons: This businesse was carryed on with such eagernesse, that during his imprisonment his own Father, though a Knight of S. Mars, was not permitted to visit &illegible; The Spaniards after they had plundered many places in Plemont, are gone over &illegible; at &illegible; and so from thence to Olegio where they are to receive their pay, and after that go to their winter quarters. The 18 came hither Marshall du Flesses, with many of his Officers, and that same evening went to our Pallace, to salute the Duke and the Dutchesse his mother. The French forces come lately from Cremona, are yet remaining in the Valley of Bennio, where they do expect the four Regiments of horse that come from France under the command of Mr. du Choupts and Bougi, Fieldmarshals, who are commanded to go to Gualtleri, and other places, belonging to the Duke of Parma, for their better accommodation; and being certified that the Spaniard intended to invade the County of &illegible; therefore the Duke hath sent with all speed D. Emmanuel of Savoy, with 2000 men to oppose them, and have an eye unto their match, and so prevent the execution of their designes.

The 3. instant the Count of Nassaw, one of the Plenipotentiaries of the Emperor, for the general Peace, arrived here, and brought with him those happy tidings of the conclusion of a general Peace in Germany, so long wished for, during 30 years, that the Wars, like a cruell wilde beast, hath almost devoured that so florishing countrey; this news being spread over the City, caused no ordinary joy in the hearts of all the people and every one, from the highest to the lowest, did make Demonstration thereof to their uttermost. The Count Trautmansdorf did send for him in his Coach, and being come, did entertain him with all Honours and Favours as could be wished or expected. There are here great preparations for dayes of mirth and rejoycing that are to be kept here very speedily, and that not only for joy and thanksgiving for the generall Peace lately concluded, but also by reason of the marriage that is shortly to be celebrated between the King of Spain and the Emperors daughter; the King of Hungaria, eldest son to the Emperor, being appointed on that day of the Nuptials, to represent his Catholick Majesty, and two dayes after she is to be conducted into &illegible; his Imperiall Majesty having given her 24 of his Gardes and six of his Pages.

Since the suspension of Arms hath been published in this City, there hath been brought hither &illegible; Pieces of Ordnance, and some part of the Train belonging: to the Imperiall and Bavarian Armies, the first of these having their head-quarters at &illegible; a league from Chamb, and the other at Roding neer the River of Regen. The French Army have their head-quarter at Rotemberg, upon the River Tauber, and the Swedish Army at Furth, but yet it is said that the Marshall of Turenne with his Army is going to &illegible; in the Dutchie of Wittemberg, and Generall Wrangel into Misnia toward &illegible;

The Zealanders having given a free passage by the Escaule, many ships are come in to us, paying only the old duties, and ancient customs, as formerly they have done; by means whereof, those of Amsterdam are in election to loose some of their Trade, there being not at present such a great number of shipping that resorts thither as in times past, during the time of the Wars. The Archduke Leopold is still at Brussels, where he hath continued some weeks past.

This week are come letters from Brasil, which gives us to understand, that our Admirall Wittens, with the Holland Fleet is gone for the river &illegible; where the West-India Company hath intended long since to make an attempt, but till now could not have any fit opportunity; what will be the successe, is dubious, and cannot be able very suddenly to give you an account thereof; this place is of great concernment to the Portugesses, yielding yearly great store of Sugars, and other rich commodities, which are transported from thence in Carvels, and brought to &illegible; it is not like therefore that it could be taken from them, unlesse by an accident it should be surprized, and so to expell from thence the &illegible;

Captain &illegible; and the rest of the Pirates taken in the &illegible; &illegible; referred to the Admiralty, to be tried as &illegible; The four Northern Counties to have the benefit of the sequestrations of the old Delinquents for their new Delinquencies, to &illegible; &illegible; and pay publike debts, 4000 li for &illegible; forces to be presently paid, &illegible; given for the same, Peter &illegible; Esq. voted Sheriff of &illegible; and &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; of Darby. Col. Temple Ordered 500 li in part of his &illegible; &illegible; of the &illegible; of the Lord &illegible;

Mr. Siedgwick, and Mr. &illegible; thanked for their &illegible; and Mr. &illegible; and Mr &illegible; to preach next fast day before the House: What, before all the House? some &illegible; have a minde to be absent to &illegible; one elsewhere. Col. &illegible; Letter, and a Copy of the Orders from the generall Councell of War, to himself and others, to secure his Majesties person, were read, and a Letter Ordered to be writ to his Excellency, to acquaint him that these Orders to Col. Ewers and others, are contrary to the Orders of Parliament, given to Col. Hamond, and that it is the pleasure of the House that his Excellency recall these Orders, and that Col. Hamond be set at liberty. A modest Letter this day came from his Excellency, desiring the consideration of the Armies Remonstrance, which take at large: Mr. Speaker,

IT is not unknown to you, how, and how long we have waited for some things from you respecting our Remonstrance, & the present condition of the Kingd. but receiving nothing in answer to the one, nor remedy to the other, We do hereby again let you know, That we are so apprehensive of the present juncture of affairs; that through &illegible; of such helps as we might have had from you, we are attending and improving the providence of God, for the gaining of such ends as we have proposed in our aforesaid Remonstrance: We desire you to judge of us as men acted in this by extremity; In which we would yet hope for the conjunction of such helps as any among you, friends to the publike interest, &illegible; &illegible; afford us, I remain,

Your most humble servant.

T. &illegible;

Windsor Novemb. 19. 1648.

For the Honourable &illegible; &illegible; Esq; Speaker of the

Honourable House of Commons.

This day the debates flew high; some moved that his Excellencies Commission might be taken from him, Others that the Army might be required to retreat 40 miles from London, and the blinde &illegible; moved that the City might be put into a posture of &illegible; but Sheriffe &illegible; answered with a sad dejected &illegible; that there was nothing to be expected from thence: And Prime began to &illegible; Presidents; that &illegible; have &illegible; voted Traytors for disobeying authority of Parliament, but for his &illegible; he would &illegible; say that any were such.

Novemb. 30. The House was divided, whether the &illegible; of the Army should be taken into consideration, and it was resolved in the negative. The Army &illegible; &illegible; for it; &illegible; &illegible; still to provoke them and the Kingdom against &illegible; Or &illegible; &illegible; proceed &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; Yet the next &illegible; is to refer &illegible; to the &illegible; of the Army to &illegible; the Arrears of the Army. &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; men &illegible; &illegible; from &illegible; The &illegible; day was spent in &illegible; Committee, to consider of &illegible; for the &illegible; Officers. &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; then the &illegible; of the Armies &illegible; Besides, how &illegible; you design &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; They &illegible; &illegible; their &illegible; to the Army, and desire to engage with &illegible; against the &illegible; and &illegible; &illegible; The &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; came forth, to &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; of &illegible; &illegible; to &illegible; &illegible; too &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; is not this very &illegible; &illegible; to give &illegible; &illegible; of &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; The &illegible; of &illegible; and &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; and the &illegible; &illegible; and &illegible; which was delivered by &illegible; &illegible; &illegible; to his &illegible; &illegible; as large, it hath &illegible; yet printed.

The humble Petition and Addresses of the well Affected in Devon and Cornewall. Together with the Officers and Souldiers of the Brigade, under Command of Sir &illegible; &illegible; Knight; now residing in the Westerne parts.

VVE your Excellencies Servants, not stirred up by any affection, to meddle with matters besides the businesse of our respective Imployments, nor any way favouring distempers amongst our selves, or others, neither covering the vaine glory of being numbred amongst Petitioners, against the evils of the times, nor highly provoked by emulation, from what others our fellow Countreymen and souldiers have done; but singly and faithfully, we come to your Excellency in this Petition, abundantly pressed thereto, from the Conscience and sense we have of the neere approach of Ruine to all honest Parties of the Kingdome, and your selfe and the Army amongst the rest, whereof the present transactions with the King, the late transactions of the &illegible; and of a prevalent party in the houses, are palpable and unhappie evidences to the world, all moulding such a closure of the present differences, as we apprehend, must certainly strengthen all the old corruptions in the former government, and so leave the Kingdome in a more-desperate bondage then yet it ever felt; And farre be it from your Excellencie, and your faithfull servants, to be silent at such a time as this, when all the honest parties of the Kingdome have such deep feares, and heavie thoughts of their, and your approaching &illegible; farre be it from your noblenesse to thinke it, besides your businesse to pitie and plead the Kingdoms cause; We professe the complaints of good men every where pierce our &illegible; and our owne observations of the just reasons of dissatisfaction, constraine us to this great boldnesse with your Excellencie, to petition you, if it were possible, with teares of bloud, seasonably to interpose your selfe in some just and honourable way, that according to the desires of other Petitioners to the Houses, and to your Excellency (an excellent Modell whereof we have before us, in the London Petition, of the 11. of September last) all disputable matters about the late troubles may be made cleare, Iurisdictions legall and just, duly limited, and ascertained against Tyrannicall and arbitrary Power, Liberty and property vindicated, and that Antichristian bloudy tenet of destroying mens lives and estates, for not beleeving as the Church beleeves, utterly abandoned; Amongst all which generalls, we further present your Excellency with a few particulars following, viz. 1. By what evidences and proofes, or upon what Reasons and grounds the King stands acquitted of the charge of the Houses against him, in their late Declaration to the Kingdome. 2. What persons especially what members of either Houses have playd the Traytors, by inviting the &illegible; to invade this Kingdome, or gave them countenance, or incouragement in that perfidious attempt. 3. That the promoters of the first and second warre be brought to Iustice. 4. That the Arrears and debts of the Kingdome be secured and satisfied, and that the publique faith be not made a publique fraud to the Kingdome. 5. That the Court of &illegible; be abolished without exacting satisfaction for the same. 6. That the unconscionable oppression of the Tynners by &illegible; be removed. 7. That the Consciences of men be not cruelly and unconscionably shipwracked. 8. That the cunning device upon the Army for hatefull free quartes, and the Contrivers thereof he discovered, and the Army vindicated from the slander thence raised upon it. 9. That inquisition may be made after the bloud of Colonell &illegible; 10. That the Orders for reducing any of the souldiers may be suspended, untill the Common-wealth be setled, and the enemies thereof brought to Iustice. That these, and the like &illegible; being satisfied and secured to the Kingdome, Your Excellency and your Army may &illegible; from this present imployment in honour, and good Conscience, as faithfully discharging the Armies ingagements to the Kingdome, and not beare the shame and reproach of men, that only acted for hire, and so that base scandall, so much in the &illegible; of your and our treacherous enemies, will not be justified in the hearts of our friends; for the effectuall obtaining of these good things, we shall really adhere to your Excellency to our utmost ability.

Westm. Decemb. 2. L. &illegible; M. Hollis, and M. Pierpoint thanked for their pains in the Treaty. And indeed two of them deserve the houses thanks, though the Kingdoms hatred; and must these thanks be given, because M. Crew took notice of their royal services? M. Hollis (the grand perfidious—of England) reports the transactions of the Treaty since their last Letters, to be prepared and brought in, and likewise a Copy of the Kings Letter to the L. Ormond, touching their proceedings with the rebels in Ireland. The quest. was, whether satisfaction, or not in the Kings Answer to the Propositions shall be now taken into consideration, and it past in the negative, but ordered to be debated to morrow. Did you vote the Kings finall answer &illegible; the last week, and do you now come to put it to the quest. and make a dispute thereof, whether satisfaction or not? When he hath granted no more now, then in his former. A Committee of Common Councell communicated his Excellencies Letter to both houses, of the grounds of the Armies advance, and desiring 40000. li. to be speedily raised for them, upon the credit of the Arrears due unto them. The City was not so civill, when the last traiterous Parl. of Scotland sent a Letter to them, to engage them for the destruction of this Kingdom, to report that to the house, but rather concealed it from them. And in this they tell the Parl. they are come down to waite upon their honourable commands. Though for almost seven years past the Parlia. hath been commanded by them. The Lords tell them they leave it to the City to do therein as they shal think fit. This is Lord like, and like Lords advice; and do not their Lordships deserve a see for it? The Commons Vote hereupon, That the house taking notice of the great Arrears due by the City of Lond. to the Army (as if they never knew, or took notice of them before, though severall times reported from the Committee of the army) do declare, that it is the pleasure of the house (how long both the City (I pray) been subject to your pleasure, or rather you to theirs) that the City do forthwith provide 40000 li (now according to the pleasure of the army) of the Armies Arrears, upon security thereof; And likewise that it be left to the City, either by Committee, Letter, or otherwise to addresse themselves to his Excellency. They likewise voted, that a Letter should be writ to the Gen. (as they call him) upon the present debates to require him not to march near London, which take at large.

May it please your Excellency: The house taking notice by your Letter of the 30 of the last moneth, to the L. Mayor, Aldermen, and Common Councel men of the City of London, and by them communicated to us, that you are upon an immediat advance hither, have commanded me to let you know, that upon mature deliberate judging, that it may be dangerous both to the City and Army (and not to your selves at all) It is their pleasure that you remove not the Army near London (whereby the grand Delinquent of the Kingdom, and you that have invited in, and joyned with a Forraign enemy, to cut our threats, and &illegible; the Kingdom, may not be brought to &illegible; punishment) And to the end the Country may not be burthened with free-quarter, nor the Army want their due support (of both which you have had a negligent care &illegible; many years together) they have commanded me to acquaint you, That they have signified their pleasure to the Lord Mayor, Aldermen, and Common Councell (their &illegible; in iniquity) that they forthwith provide the sum of 40000 li. as part of their Arrears, (though they owe neer 100000 li. arrears &illegible; the 25 of January last, and neer 200000 li. before,) or so much thereof as they can possibly raise at present, and pay the same to the Treasurers at Wars, to be forthwith sent unto you for our Army, which being all I have in Command, I remain your Humble servant,

William Lenthall, Speaker.

Before the receipt of his Letter the Army &illegible; then at Kensington, within two miles of the City of London, the next morning drew up into Hide Park, and about 12 of the clock that day, after a Rendezvoux there, advanced to Westminster, (White Hall being made the head quarters) and the whole Army quartered there, in the Mews, Suffolk house, and elsewhere in Westminster. A little before His Excellencies drawing out of the Park, a Committee of Common Councell &illegible; from the City to congretulate his approach, telling him. The Gates of the City should be open for him, though the next day after, a Troop of horse comming out of Essex, was denied to passe thorow the City to the Head Quarters at White Hall, for which the Lord Mayor and Sheriffs (by whose Order the Gates were &illegible; upon their) may be considered in due time.

SIR,

THis morning about six of the Clock five of us came to his Majesties &illegible; and desired one of his Attendants to acquaint his Majesty with our &illegible; (according to our Orders) to secure his person, which we rather did, because he might not be affrighted; which done, we secured the Town with 40 horse, and two companies of &illegible; which we got over last night from Portsmouth, and once in half an hour his Majesty was &illegible; and soon after secured in Hurst Castle, of which our dear friend, and true Patrior, Col. &illegible; of Willshire is Governor, whose fidelity can never be poysoned as H. was. I am yours, &illegible;

Postscript. There are Attendants upon his Majesty in Hurst Castle, Capt. Mildmay Capt. Joymer, Capt. Weston, Mr. Herbert, Mr. Cutchside, Mr. Reading, Mr. Harrington, Mr. &illegible; Mr. Leven Page of the Presence. This day his Excellency caused this ensuing Proclamation to be made at the head of every Regiment, viz.

These are to require all Officers and Souldiers of Horse and foot, who shall quarter in and about the City of London, and Suburbs thereof. That they behave, and &illegible; themselves civilly, and peaceably towards all sorts of people, not giving any just cause of offence, or provocation by Language, or otherwise, upon paine of such severe punishment, &illegible; Court Martiall shall be thought meet, and not doe any unlawfull violence to the &illegible; or goods of any, either in their Quarters, or elsewhere, upon paine of death. And for the more due execution hereof, all Commanders and Officers are hereby required, not to be absent from their severall and distinct charges, without leave first had in writing from &illegible; superious, upon &illegible; of such punishment, as that party injured shall sustain, and such &illegible; ceasure as to justice shall be thought sit. Given under my hand Decem. 1. 1648. &illegible; &illegible;

To be proclaimed by sound of Trompet, or beat of Drum at the head of the Regiment.

Pontefract the 2 of December. The Lieut. Gen. being gone to London, Maj. &illegible; &illegible; is appointed to come in chief to this Leaguer. The Line is drawn 3 parts about the Castle, and we are now raising works for Batteries; and though the enemy are &illegible; that they dare not stirre forth, yet are very active both with great & small shot, and sometimes do us hurt; they have very few or no horse in the Castle, except for their necessary uses, &illegible; some of their men daily come from them; they are yet about 300 in the Castle, &illegible; &illegible; others; the souldiers are very poorely clad, and cannot be induced to make a salley, divers of them as they say are fallen sick, at least 60. at this time; they have plenty of all sorts of provisions for a &illegible; and if nothing else hinder, they will not be starved in 12 moneths. The cruelties of &illegible; the Governour of this Castle to our prisoners, are not to be &illegible; all of them that either have escaped, or been released &illegible; lamentable complaints of him. We much rejoycee in your Remonstrances, but all our feare is that the Army will do nothing considerable upon it; which feare lies upon many honest spirits, who cannot joyne affectionately with us, till they see justice be done indeed upon the grand Delinquent, and his consederates in Parliament and City; without speedy execution of whom, we never expect peace or blessing to the Nation.

Decemb. 5 &illegible; house sate very &illegible; debating whether the Concessions of his Major to the Propositions were satisfactory, or not; at ten at night they had not decided the question &illegible; would think this labour might be saved. A proclamation this day made by beat of Drum and sound of Trumpet, requiring all in the latter and former Wars (having not perfected their Compositions) to depart the late Line, ten miles distant for a moneth or &illegible; to be &illegible; against as prisoners of War.

FINIS.

The Moderate: Impartially communicating Martial Affaires to the Kingdom of ENGLAND.

From Tuesday Decemb. 5. to Tuesday December 12. 1648.

WE finde in History, That the next in succession to the Crown, by Propinquity of blood, have oftentimes been put back by the Common wealth, and others farther off admitted in their places, even in those Kingdoms where succession prevaileth: for proof whereof, I shall begin with &illegible; a true and lawfull King over the Jews, and consequently had all Kingly Priviledges, benefits and Prerogatives belonging to that degree, yet after his death we finde God suffered not any one of his generation to succeed him, though he left behinde him many children, and among others, Isboseth, a Prince of forty years of age, 2 Kings 2. 21. whom Abner, the generall Captain of that nation, with eleven Tribes, followed for a time as their lawfull King by succession, untill God checked them for it, and induced them to reject him; though heir apparent by descent, and to cleave to David newly elected King, who was a stranger by birth, and no kin at all to the King deceased: And David being placed in the Crown by election, free consent, and Admission of the people of Israel, and no man, I think, will deny but that he had given unto him therewith all Kingly Priviledges, Preheminencies and Regalities, even in the highest degree; and though God did assure him that his seed should raign after him, yea, and that forever; yet we do not finde this to be performed to any of his elder sons, (as by order of inccession it should seem to appertain) no, nor to any of their off-springs, or descents, but only to Solomon, which was his yonger, and tenth son, and the fourth only by &illegible;

What can give more evident proof hereof, then that which ensued afterwards to Prince Robosm, the lawfull son and heir to King Solomon, who, after his fathers death, coming to Sichem where all the people of Israel were gathered together, for his Coronation, according, to his right by succession, 3 Kings 12. And because he refused to take away some heavy impositions laid upon them by his father Solomon, Ten Tribes of the twelve refused to admit him their King 3 Kings 11, but chose rather one &illegible; Roboams servant, that was a meer stranger, and of poor parentage, and made him their lawfull King, and God allowed thereof, as the Scripture in expresse words doth testifie. I shall not mention any example of forraign nations, being without number, but give you some of our own, having had as great variety in Changes, and diversity of Races of their Kings as any one Realm in the world: for first, after Brittains, it had Romans for their Governors for many years; after that, they had Kings again of their own, as appeareth by that valiant King Auretius Ambrosim who resisted so manfully the Saxons; after this they had Kings of the Saxon and English blood, and then of the Danes, then of the Normans, and after them again of the French, and last of all it seemeth to have returned to the Brittains again in King Henry the seventh, King &illegible; King of the West Saxons, and almost of all the rest of England, who was the first Monarch of the Saxons blood, was had in jealosie by King Briticus, (who was the sixteenth King from &illegible;) and for that he suspected Edgebert for his great Prowesse, be banisht him into France, and after that King Briticus was dead, he returned into England, and was then chosen King by the people, though he was not next in propinquity of blood royal.

This King Edgebert, (or Edgebrick as others write him) left a lawfull son behinde him, named &illegible; or Edolph, Anno 829. who succeeded him, having four lawfull sons, and because one of them (Alfred) was esteemed more valiant then the other &illegible; he was preferred to the Crown before them (though the yongest of them all,) and was Crowned at the Town of Kingston.

This man dying without issue, his lawfull brother Edmund put back before, was admitted to the Crown, and left two lawfull sons, but yet because they were young, they were both put back by the Realm, and their uncle Eldred preferred before them.

King Iohn was after the death of his brother crowned by the States of England, and Arthur Duke of Boktaine, son and heir to Ieffery, that was eldest brother to Iohn, was against the order of succession excluded.

Some years after when the Barons and States of England misliked utterly the government and proceedings of this King Iohn, they rejected him, and chose &illegible; the Prince of France to be their King.

Moreover from King H. 3. do take their first beginning York and Lancaster, into which, if we would enter, we should see plainly, as before hath been noted, that the best of all their Titles after their Deposition of K. R. 2. depended of this Authority of the Commonwealth, for that as the people were affected, and the greater part prevailed, their titles were allowed, confirmed, altered, or disanulled by Parliament.

VPon the drawing up of the Army to this place, for the better avoiding the trouble and inconaeniencies to the City and Suburbs of LONDON, or the Inhabitants thereof, which might happen by the quartering of Souldiers in private mens houses, it was the desiro and Resolution of my self, and my Officers, to lodg. the Souldiers in great and void houses; and to the end they might be accommodated for that purpose, (in regard, that at this season Souldiers cannot hold out to lodge continually upon bare floors,) I writ to the Lord Major, Aldermen, and Common Councel of the City of LONDON, desiring they would take some course for a speedy supply of Bedding for the Souldiery: but instead of any satisfaction therein, after some delay, I have received only an excusatory Answer.

The Souldiers and most of the Officers having &illegible; now almost a week upon cold floors, and health not permitting them to endure such hardship for continuance, out of the same tender care, to avoid trouble or inconvenience to the inhabitants, or any discontents or differences which might arise between them and the Souldiers, by the quartering of them in private houses, I have (with the advice of a Councel of War) thought fit to require a necessary supply of Bedding, by Warrants directed immediatly to the respective Aldermen of the severall Wards, the Copy whereof is herewith printed and published; and (with the same advice) I do hereby further declare, That in case any failer shall be in the bringing in by the time limited, such proportions of Bedding, as, according to the said Warrants, are charged upon the severall Wards, and shall be apportioned upon the several Divisions and Inhabitants of the same, I shall be necessitated to send Souldiers, either to fetch such proportions of Bedding from them that fail, or else to quarter with them, and must take such course against either those Aldermen, and other Officers in the City, who shall neglect to rate and bring in the proportions required from their respective Wards and Divisions or against those Inhabitants who shall refuse to supply the proportions rated upon them, as shall be fit to use towards such obstinate opposers of that orderly supply, which is so necessary for the case and quiet of the City, and for the subsistance of the Army.

Given under my Hand and Seal, at my Quarter in Westminster, the eighth of December, 1648.