Introduction to Cobden and the League (1845)

T.27 Introduction to Cobden and the League (June 1845)

Translation corrected: began 3 Dec. 2015

Footnotes & Glossaries added:

Source

T.27 (1845.06) Cobden et la ligue, ou l’Agitation anglaise pour la liberté du commerce (Paris: Guillaumin, 1845) (Cobden and the League, or the English Movement for Free Trade). FB's first book was reviewed in the July 1845 edition of JDE, T. 11, no. 44, p. 446 so it was probably published in June. It consists of a lengthy "Introduction" by Bastiat, which we include in the CW6, and his lengthy summaries and translations of meetings, newspaper accounts, and other material produced by the Anti-Corn Law League (which we do not include). FB's "Introduction" to Cobden et la Ligue (1845), pp. i-xcvi. [OC3, pp. 1-80.] [CW6]

An extract from this Introduction was also published as a separate article in JDE June 1845 ???

Editor’s Introduction (to do)

Text

The person most in danger of deceiving himself as to the worth and significance of a book, after the author, is undoubtedly the translator. Maybe I am no exception to the rule, for I have no hesitation in saying that the one I am publishing, if it were to be read, would be a sort of revelation for my country. Freedom, as far as trade is concerned, is seen here in France as a utopia, if not worse. People acknowledge the truth of the principle in the abstract; they are willing to recognize that it may befittingly feature in a theoretical work. But they go no further. They even credit it with being true on one condition only: that, along with the book that contains it, it remain forever relegated to dusty libraries, that it have no influence over common practice, and that it hand over the scepter of business to the opposing, and therefore abstractly false, principle of prohibition, restriction, and protection. If there still remain a few economists who, in the midst of the desert that has spread around them, have not altogether relinquished their sacred belief in the dogma of freedom [le dogme de la liberté], they hardly dare, with unsure gaze, search the distant future for its doubtful triumph. Like seeds covered with thick layers of inert soil and that will only germinate when some cataclysm has brought them to the surface and exposed them to the invigorating rays of the sun, those economists see the sacred germ of freedom [e germe sacré de la liberté = seed] buried under the hard shell of passions and prejudices, and they dare not reckon how many social revolutions will have to take place before it comes into contact with the sun of truth. They are not aware, at least they do not appear to be aware, that the food of the strong [le pain des forts = bread], converted into milk for the weak, has been distributed unstintingly to the whole of a present-day generation; that the great principle of the right to exchange has broken out of its shell, has poured forth like a torrent over people’s intellects [les intelligences = minds], is the driving force of an entire great nation, has built up an indomitable public opinion [opinion publique indomptable = ?? unshakeable], will take possession of human affairs, and is about to take over the economic legislation of that great nation!

That is the good news contained in this book. Will it reach your ears, you lovers of freedom, you partisans of union between nations, you advocates of the universal brotherhood of mankind, you who defend the working classes, without arousing in your hearts confidence, eagerness, and courage? Indeed, if this book could force its way under the cold stone that covers the likes of De Tracy, Say and Comte,

I believe the bones of those renowned philanthropists would start with joy in their graves.

But, alas! I have not forgotten the condition that I myself set: If this book succeeds in being read. – COBDEN! LEAGUE! LIBERATION OF TRADE! – What is Cobden? Who in France has ever heard of Cobden?

It is true that posterity will associate his name with one of those great social reforms that now and then mark the progress of Mankind along the course of civilization: the restoration, not of the right to work, as current talk has it, but of the sacred right of work [working] to its fair and natural remuneration [payment].

It is true that Cobden is to Smith as propagation is to invention; that, with the help of his many comrades in enterprise [compagnons de travaux = work mates?? in the field], he has popularized social sciences; that by dispelling in the minds of his fellow countrymen those prejudices that serve as a foundation for monopoly, that domestic spoliation [plunder], and for conquest, that spoliation abroad, and that by thus destroying the blind antagonism that sets class against class and nation against nation, he has prepared for mankind a future of peace and brotherhood [fraternité = ],

not founded on some chimerical self-sacrifice, but on the indestructible desire of individuals for their own preservation and progress, a feeling that people have attempted to stigmatize under the name of enlightened self-interest [e nom d’intérêt bien entendu = self-interest properly understood], but to which it undeniably pleased God to entrust the preservation and progress of humankind. It is true that the above mission has been carried out in our time, under the same sky, on our doorstep, and that it is still stirring to its very foundations a nation whose every move usually concerns us to excess [préoccuper à l’excès = excessively]. And yet, who has ever heard of Cobden? Good Lord! We have better things to do than to busy ourselves with what is, after all, only in the process of changing the face of the world. Haven’t we to help Mr. Thiers to take Mr. Guizot’s place, or Mr. Guizot to take Mr. Thier’s?

Are we not threatened with a fresh invasion by barbarians, in the shape of Egyptian oil or Sardinian meat?

And would it not be a shame for us to turn our attention, even for a moment, to free communication between nations, when that attention is so usefully taken up with Noukahiva, Papeete and Muscat?

The League! What is this League? Has England given birth to some Guise or some Mayenne? Are Catholics and Anglicans going to have their own battle of Ivry?

Has the agitation to which you refer anything to do with the unrest in Ireland?

Are there going to be wars, battles, bloodshed? In that case our curiosity might well be aroused, for we simply love games of brutal force, and we do take such an interest in religious questions! We have become such good Catholics, such good Papists, recently.

The liberation of trade ! What a disappointment! What an anticlimax! Is the right to exchange, if it is a right, worth our bothering about ? Freedom to speak, to write, to teach, fine; we can think about such matters from time to time, in a spare moment, when the all-important question, the ministerial question, grants our faculties a few instants’ respite, for, after all, those liberties concern men of leisure. But freedom to buy and sell! The freedom to dispose of the fruit of one’s work, to derive from it, through exchange, all that it can yield, why, that also concerns the masses [le peuple = the people], the laborer [l’homme de labeur = the man of labour, the labouring man], it has to do with the worker’s life. Besides, to exchange, to barter [trafiquer = to traffic in goods?? troc = barter], is so prosaic! And then it is no more than a question of well-being and justice. Well-being! why, that is too concrete, too materialistic for a century of abnegation [sacrifice] such as ours! Justice! Why, that is too cold a notion. If only it were a matter of almsgiving [italic??], then there would be grand things to say. And is it not pleasant to persevere in the course of injustice, when at the same time one is as prompt as we are to display charity and philanthropy?

“The die is cast”, cried Kepler, “I’ll write my book. It may be read in the present age or hereafter; what do I care? It can await its reader.”

– I am not Kepler, I have uncovered none of Nature’s secrets; I am but a plain and very mediocre translator. And yet I dare to say as that great man said: This book can wait: sooner or later the reader will come to it. For after all, even if my country continues to lull itself for some time in that willful ignorance which it seems to enjoy, with regard to the immense revolution that is causing the whole of Britain to seethe, one day it will be struck with amazement at the sight of that volcanic fire.....no, of that salutary light [lumière bienfaisante = nurturing, beneficial, regenerative] that it sees shining to the north. One day, and that day is not far off, the country will, abruptly and without any forewarning, hear this great news: England is opening up all its ports; it has overturned all the barriers that cut it off from other nations; it used to have fifty colonies, it now has only one, which is the whole universe; it will trade with whoever wishes to trade; it will buy without demanding to sell [sans demander à vendre = the right to sell, sales in return??]; it will accept all relations without insisting on any in particular; it welcomes invasion by your products; England has freed labor and trade. – Then, maybe, people will want to know how, by whom, and since when that revolution was prepared; in what impenetrable cellar, in what unknown catacombs it was plotted, and which mysterious network [franc-maçonnerie mystérieuse = secret society] tied all the threads together; and this book will be there to answer: Why, it all took place in full sunlight, or at least in the open (for there is said to be no sun in England). It was accomplished in public, through a debate that lasted ten years and was sustained simultaneously all over the land. That debate led to an increase in the number of English newspapers and to an expansion in their size; it gave birth to thousands of tons of brochures and pamphlets; its progress was anxiously followed in the United States, in China, and even among the savage tribes of African Negroes [des noirs Africains = Africans]. You Frenchmen alone had no inkling of it. And why so? I could say why, but would it be wise? Never mind! Truth is pressing me and I will speak out. The fact is that there are in our midst two great corrupting forces that bribe our sources of information [soudoient la publicité= corrupt, poison, distort]. One is called Monopoly, and the other Party bias [Esprit de parti. = ??]. The former said: I need hatred to come between France and other countries, because if nations didn’t hate one another, they would eventually understand one another, unite, like one another, and maybe – what a horrible thought! – exchange between them the fruits of their industry. The latter said: I need hostility between nations, because I aspire to power; and I will achieve it if I manage to surround myself with as much popularity as I can wrench from my opponents, by showing them to be in the pay of some foreign power that is ready to invade us, and by presenting myself as the savior of the land [patrie = homeland, father land, country]. – So an alliance was concluded between monopoly and party bias, and it was decreed that any publication about what took place abroad would employ the following means: concealment and distortion [Dissimuler, dénaturer = ]. Thus France was systematically kept in the dark about the event that this book aims to reveal. But how did the newspapers manage to do this? You are surprised? – Well, so am I. But manage they undoubtedly did [leur succès est irrécusable = but their success is/has been undeniable].

However, and precisely because I am going to take my readers (if I have any readers) into a world that is completely unknown to them, I must be allowed to preface this translation with a few general observations on the economic system in Great Britain, on the causes which gave birth to the League, on the spirit and significance of that association from the social, moral, and political points of view.

It has been said and it is often repeated that the Economist school of thought, which entrusts the interests of the various classes of society to their own natural (law of) gravitation [à leur naturelle gravitation =], originated in England; and, with surprising levity [légèreté = quickness], people have jumped to the conclusion that the appalling contrast of wealth and poverty that characterizes Great Britain is the result of the doctrine proclaimed with so much authority by Adam Smith and so methodically [tant de méthode = rigorously] explained by J.B. Say.

People seem to believe that liberty reigns supreme on the other side of the Channel and that it is responsible for the unequal distribution of wealth there.

Just recently Mr. Mignet, speaking of Mr. Sismondi, said “He had witnessed the great economic revolution accomplished in the present time. He had watched and admired the wonderful effects of those doctrines that had freed labor and overturned the barriers that guilds, master craftsmen, interior customs, and multiple monopolies had erected against the products of labor and their exchange; and which had given rise to an abundant production of assets [des valeurs = valuable goods, things of value] and their free circulation, etc.

But soon he had probed further and had come up against sights less fit to arouse his pride in the progress of Mankind [l’homme = ] or reassure him as to its happiness, in the very country where the new theories had most speedily and completely been developed, in England where they reigned supreme [avec empire = ]. What had he seen there? All the splendor, but also all the excesses of unlimited production,... each closed market reducing whole sections of the population to dying of hunger; the disorder stemming from competition, that is to say, interests in their natural state, which is often more murderous than the ravages of war; he had seen man reduced to being a mere cog in a machine more intelligent than himself, crammed into unhealthy premises where life did not attain half its normal span, where family relationships broke down and notions of morality were lost...In short, he had seen extreme poverty and appalling degradation regrettably offsetting and secretly threatening the prosperity and splendors of a great nation.

Surprised and troubled, he wondered whether a science that sacrificed man’s happiness to the production of riches... was truly a science...From that moment on, he maintained that economics should concern itself far less with the abstract production of wealth than with its fair distribution.”

Let it be said in passing that economics is no more concerned with the production (even less with the abstract production) of wealth than with its distribution. It is work and exchange that have the above as their object. Economics is not an art, but a science. It enforces nothing, it does not even recommend anything, and consequently it does not sacrifice anything; it describes how wealth is produced and distributed, just as physiology describes the way our organs function; and it is just as unfair to blame the former for the ills of society as it would be to attribute to the latter the diseases that afflict the human body.

At all events, the widely-held notions that Mr. Mignet expounded all too eloquently naturally lead to arbitrary attitudes. At the sight of that shocking inequality which economic theory or, to put it plainly, which liberty is supposed to have engendered in the very place where it reigns most supremely, it is only natural that liberty should be accused, rejected, stigmatized, and that people should take refuge in artificial social arrangements, in * “the organization of work”, in mandatory associations between capital and labor, in a word, in utopias where freedom is sacrificed to begin with, as being incompatible with the reign of equality and brotherhood between men.

It is not part of our present subject to expound the doctrine of free trade nor to combat the many expressions of those schools of thought which today usurp the name of socialism and have nothing in common but that usurpation.

But it is essential to make the following clear here and now: the economic regime of Great Britain is far from being based on the principle of freedom; wealth there is by no means distributed in a natural way; and finally it is far from being the case that, as *Mr. Lamartine so nicely put it, thanks to free enterprise every activity obtains results such as no arbitrary system could offer. In fact, there is no country in the world, save those still cursed with slavery, where Adam Smith’s theory – the doctrine of laissez-faire, of non-interference - is less put into practice than in England, and where the exploitation of man by man has been more systematically developed.

And it should not be imagined, as some might argue, that it is precisely free competition that eventually brought about the subjection of labor to capital, of the working class to the idle. No, that unjust domination cannot be considered to result from, nor even to be a misapplication of, a principle that never guided British industry. In order to determine the origin of that domination, one would have to go back to an era that was most certainly not a period of freedom: to the conquest of England by the Normans.

But without retracing the history of the two races that tread the soil of Britain and who fought each other in so many bloody battles over civil, political and religious matters, it is appropriate here to recall their respective positions from the economic point of view.

The English aristocracy, as you know, owns all the land in the country. Moreover, they hold the legislative power. The question is simply: have they used that power in the interests of the community or in their own interests?

In Parliament, Mr. Cobden addressed the aristocracy itself in these words, “If our financial system, our statute book, could reach the moon, alone and without any historical commentary, it would take nothing more to show its inhabitants that it was the work of an assembly of landlords.”

When an aristocratic breed has both the right to make laws and the strength to enforce them, it is unfortunately only too true that they will legislate to their own advantage. That is a painful truth, which will, I know, sadden those kindly souls who rely, to remedy unjust practices, not on the reaction of those who suffer such practices, but on the free and brotherly initiative of those who exploit them. I wish someone could point out to me an example in history of such abnegation. But there has never been any example of it, be it among the upper castes in India, or among the Spartans, Athenians and Romans who are forever being held up to our admiration, or among the feudal lords of the Middle Ages, or the planters of the West Indies, and it is even most improbable that all those oppressors of mankind ever considered their power to be either unjust or illegitimate.

If one looks into what one could call the inevitable necessities of aristocratic breeds, one soon perceives that they are considerably modified and aggravated by what has been called the principle of population.

If the aristocratic classes were by nature stationary; if they were not endowed, like all other classes, with the ability to multiply, some degree of happiness and even of equality might be compatible with a regime resulting from conquest. Once the land had been shared out between the noble families, each of them would hand down its estates, generation after generation, to its only descendant, and one can imagine that in such a situation it would not be impossible for a working class to grow and prosper peacefully alongside the conquering race.

But conquerors multiply rapidly just like plain proletarians. While the frontiers of the country are unalterable, while the number of manorial estates remains the same, - because, so as not to weaken its power, the aristocracy is careful not to divide them up and hands them down in their entirety from eldest son to eldest son, - many families spring from the younger sons and multiply in their turn. These families cannot support themselves through work, since in the eyes of the nobility work is degrading. So there is only one means of providing for them, and that means is the exploitation of the working classes. External exploitation corresponds to war, conquests, colonies. Internal exploitation corresponds to taxes, government offices, monopolies. Civilized aristocracies usually practice both forms of exploitation; primitive aristocracies are compelled to deny themselves the latter form for a very simple reason, which is that there is no working class around them to despoil. But should the resources of external exploitation also happen to be lacking, what becomes of the children born of the younger branches of those primitive aristocracies? What becomes of them? They are smothered; for it is in the nature of aristocracy to prefer death itself to work.

“In the archipelagoes of the vast Ocean, the younger sons have no share in their father’s estate. They can therefore live only off the food given them by their elders, if they remain within the family; or off what may be given them by the enslaved population, if they enter the military association of the arreoys. But, whichever of the two choices they make, they cannot hope to perpetuate their race. The fact that they are unable to hand down any property to their children and maintain them in the status in which they are born, is no doubt what drove them to make a rule of smothering them

English aristocracy, although influenced by the same instincts as those that motivate Malay aristocracy (for circumstances vary, but human nature is the same the world over), found itself in a more favorable environment, if I may say so. Facing it and under it, the English aristocracy had the most hard-working, active, persevering, energetic and, at the same time, the most docile population in the world; it methodically exploited that population.

Nothing has ever been more vigorously devised or more resolutely carried out than that exploitation. The ownership of the soil puts legislative power in the hands of the English oligarchy; through legislation, this class systematically robs industry of its riches. Those riches are used by the oligarchy to pursue the policy of encroachments abroad that has subjected forty-five colonies to Great Britain; and those colonies in turn serve as a pretext for levying heavy taxes, large armies and a powerful navy, all at the expense of industry and to the advantage of the younger branches of aristocratic families.

We must give the English oligarchy its due. In its twofold policy of internal and external exploitation, it displayed remarkable cleverness. Two words, which imply two prejudices, were all it needed to win over the very classes that bear all the burden of its policy: it called monopoly Protection and it called the colonies Outlets.

Thus the existence of the British oligarchy, or at least its legislative power, is not only a curse for England, it is furthermore a permanent danger for Europe.

And if that is the case, how is it possible for France to pay no attention to the mighty struggle in which the spirit of civilization and the feudal spirit are engaged before its very eyes? How is it possible for France not to know so much as the names of those men worthy of all the blessings of mankind: Cobden, Bright, Moore, Villiers, Thompson, Fox, Wilson, and a thousand others who dared go into action and who are keeping up the struggle with admirable talent, courage, devotion and energy? It is purely a question of commercial freedom, people say. Can’t they see that free trade will deprive the oligarchy of both the resources of internal exploitation, - monopolies, – and the resources of external exploitation, - colonies, - since monopolies and colonies are so incompatible with freedom of exchange, that they are nothing other than the arbitrary limit to that freedom.

But what am I saying? If French people are vaguely aware of the fight to the death that will settle the future of man’s freedom for a long time to come, they do not seem to be in favor of the triumph of liberty. For the past few years, they have been made to feel so scared of the words freedom, competition, over-production; they have been told so often that those words imply destitution, poverty, degradation for the working classes; they have heard it repeated so often that there is an English form of economics that uses liberty as an instrument of Machiavellianism and oppression, and a French form of economics, which, under the names of philanthropy, socialism, and organization of labor, is going to restore social equality on earth, - that they have taken a horror to a doctrine that is, after all, based only on justice and common sense, and which can be summed up in this axiom: “Let people be free to exchange between themselves the fruits of their labor whenever it suits them.” – If the current campaign against liberty were conducted only by imaginative souls, who wanted to formulate science without any preparatory study, it would be no great evil. But is it not a pity to see true economists, no doubt driven by a passion for popularity, however short-lived, yielding to that affected rhetoric and pretending to believe what they assuredly do not believe, that is, that poverty, the proletariat and the sufferings of the lowest social classes are to be attributed to what is called excessive competition and over-production?

Would it not clearly be most surprising if poverty, destitution and the deprivation of products had as their cause...what? Precisely the overabundance of products? Is it not peculiar that we should be told that if people do not have enough to eat, it is because there is too much food in the world? Or that if they do not have the wherewithal to clothe themselves, it is because machines cast too many clothes onto the market? Assuredly, poverty in England is an indisputable fact; the disparity between rich and poor is striking. But why seek out such a strange cause for those phenomena, when they can be explained by so natural a cause: the systematic exploitation of the workers by the idle?

At this point I must describe the economic regime in Great Britain, as it was during the last years preceding the partial, and in some respects deceptive, reforms that the present government has submitted to Parliament since 1842.

The first thing that strikes one in our neighbors’ financial legislation, and which cannot but astonish landowners on the Continent, is the almost total absence of land tax, in a country burdened by such a heavy debt and such a vast administration.

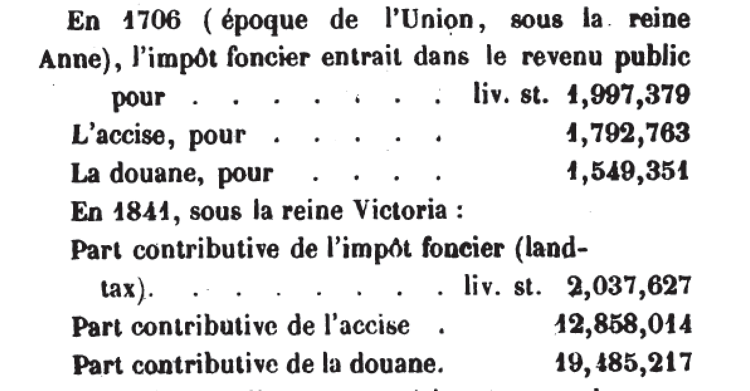

In 1706 (at the time of the Act of Union, under Queen Anne), this was the share of public revenue made up

by land tax: £1 997 379 sterling

by excise tax: £1 792 763

by customs duty: £1 549 351

In 1841, under Queen Victoria,

share made up by land tax: £2 037 627

by excise tax: £12 858 014

by customs duty: £19 485 218

Thus, direct tax remained unchanged, while taxes on consumption increased tenfold.

And one should bear in mind that, during the same period, ground rent or landowner’s income increased by a ratio of 1 to7, so that the same estate that contributed 20 per cent of a person’s income tax under Queen Anne, today contributes less than 3 per cent.

You will also note that land tax makes up only one twenty-fifth of public revenue (£2 million out of the £50 million that constitute the overall revenue). In France, and in the whole of continental Europe, land tax makes up the largest portion of public revenue, if one adds to the annual tax the duties levied on transfers and inheritances. On the other side of the Channel, real estate is not subject to the above duties, although personal and industrial property is, and rigorously so.

One finds the same unfairness in indirect taxes. As they are uniform, instead of being graded according to the quality of the goods on which they are levied, it follows that they weigh incomparably more heavily on the poor than on the wealthy classes.

Thus pekoe tea costs 4 shillings and bohea tea 9 pence; the duty on both teas being 2 shillings, the former is taxed at a rate of 50% and the latter at a rate of 300%.

Thus refined sugar costs 71 shillings and unrefined sugar 25 shillings, so that the fixed duty of 24 shillings represents 34% for the former and 90% for the latter.

Similarly, ordinary Virginia tobacco, the poor man’s tobacco, pays 1 200% duty and Havana 105%.

The rich man’s wine gets off with 28%. The poor man’s wine pays 254%.

And so on for all the rest.

Then there is the Corn and Provisions Law, which one must fully appreciate.

The Corn Law, by banning foreign wheat or by levying on it exorbitant import duties, has as its aim to raise the price of home-grown wheat, as its pretext the protection of agriculture, and as effect an increase in income for landowners.

That the Corn Law aims to raise the price of home-grown wheat is acknowledged by all parties. By the Law of 1815, Parliament quite openly claimed that it would maintain wheat at 80 shillings per quarter; by the Law of 1828, it sought to secure a price of 70 shillings for the producers. The Law of 1842 (subsequent to Mr. Peel’s reforms, and which consequently does not concern us at this point) was calculated to prevent the price from falling below 56 shillings, which we are told is only just profitable. It is true that those Laws often failed in their objective; and, at this very moment, the farmers, who had relied on that decreed price of 56 shillings and signed their leases accordingly, are being forced to sell at 45 shillings. That is because, within the natural laws that tend to reduce all profits to a common level, there is a force that despotism cannot easily overcome.

On the other hand, it is no less obvious that the alleged protection for agriculture is a pretext. The number of farms for lease is limited; the number of farmers or potential farmers is not. Therefore, the competition existing between them forces them to be content with the barest profits to which they can confine themselves. If, as a result of the high price of cereals and livestock, farming were to become a very lucrative occupation, the landlord would not fail to raise the cost of the lease, and he would do so all the more easily as, in those circumstances, farmers would volunteer in considerable numbers.

Finally, that the landlord eventually reaps all the benefit from this monopoly can leave no one in any doubt. The surplus of the price extorted from the consumer has to go to somebody; and since it cannot stop at the farmer, it must perforce go on to the landowner.

But exactly how great is the burden that the wheat monopoly imposes on the English population?

To know the answer, one has only to compare the price of foreign wheat, at the warehouse, and the price of home-grown wheat. The difference, multiplied by the number of quarters consumed annually in England, will give the exact measure of the spoliation legally carried out by the British oligarchy in this matter.

Statisticians disagree. They probably indulge in some exaggeration one way or the other, according to whether they belong to the party of the plunderers or the plundered. The authority that should inspire most confidence is no doubt that of the officers of the Board of Trade, called upon to solemnly express their views before a select committee of the House of Commons.

Sir Robert Peel, presenting the first part of his financial scheme in 1842, declared: “I believe that one should have every confidence in Her Majesty’s government and in the proposals that it sets before you, especially as the attention of Parliament was seriously drawn to these matters during the solemn enquiry of 1839”

In the same speech, the Prime Minister further said: “Mr. Deacon Hume, whose loss I am sure not one of us does not deplore, established that the country’s consumption amounts to one quarter of wheat per inhabitant.”

So the authority on which I am going to base my arguments lacks nothing, neither the competence of the man who expressed his views, nor the solemnity of the circumstances in which he was called upon to express them, nor even the official sanction of the Prime Minister of England.

On the subject with which we are dealing, the following is an extract from that remarkable exchange of question and answer:

**** Rechercher original de p.18. Intégral + références: p.431 éd.Guillaumin

Another official from the Board of Trade, Mr. MacGregor, answered:

“I consider that the taxes levied in this country on the riches produced thanks to the work and genius of its inhabitants, through restrictive and prohibitive duties, far exceed, probably by more than double, the sum total of the taxes paid to the Treasury.”

Mr. Porter, another distinguished member of the Board of Trade, well known in France for his work on statistics, testified to the same effect.

We can therefore take it as certain that the English aristocracy, through the implementation of the sole Corn and Provisions Law, robs the people of a portion of the product of its labor, or, which comes to the same thing, of a portion of the legitimately acquired satisfactions that the population could allow itself, a portion that amounts to 1 billion per year, and maybe 2 billion if one takes into account the indirect effects of that law. That is strictly speaking the share that the lawmaking aristocrats, the eldest sons, attributed to themselves.

It remained to provide for the younger sons; for, as we have seen, the aristocratic classes are no more than others bereft of the ability to multiply and, on pain of appalling family strife, they must guarantee a decent future for the younger branches of the family, - that is to say, excluding work, in other words, through theft, - since there are and there can be but two means of acquiring: by producing or by robbing.

Two fertile sources of income were made available to the younger sons: the Treasury and the colonial system. To tell the truth, those two entities are all one. Armies, a navy, in short, taxes are levied in order to conquer colonies, and colonies are maintained in order to justify the permanence of the navy, the armies or the taxes.

As long as people were able to believe that the exchanges that took place between the parent state and its colonies, by virtue of a reciprocal monopolist contract, were of a different and more advantageous nature than those that take place between free countries, the colonial system was able to find support through the nation’s misconception. But when science and experience (science being but methodical experience) demonstrated beyond any doubt this simple truth: products are exchanged for products, it became obvious that the sugar, coffee, and cotton that one receives from abroad offer no fewer outlets for domestic industry than those same products coming from the colonies. Hence, the colonial system, which is moreover attended by so much violence and so many dangers, no longer has any reasonable or even specious motive to sustain it. It is nothing more than a pretext and an opportunity for tremendous injustice. Let us try to calculate its extent.

As far as the English population, I mean the productive class, is concerned, it gains nothing from the vast expansion of its colonial possessions. Indeed, if people are rich enough to buy sugar, cotton and timber, what does it matter to them whether they order those products from Jamaica, India, and Canada, or from Brazil, the United States and the Baltic? After all, the labor of English factory workers has to pay for the labor of the West Indian farm workers, just as it would pay for the farm labor of Northern nations. So it is madness to take into account the alleged outlets opened up to England by its colonies. The country would have those outlets even if the colonies were liberated, simply by purchasing goods there. In addition, it would have foreign outlets, of which it deprives itself by restricting its procurement of supplies to its colonies and granting them the monopoly thereof.

When the United States declared their independence, prejudice in favor of colonialism was at its height, and everybody knows that England believed its trade to be ruined. It believed this so strongly that it ruined itself beforehand in military expenses in order to retain that vast continent under its dominion. But what happened? In 1776, at the start of the War of Independence, English exports to North America amounted to £1 300 000; they totaled £3 600 000 in 1784, after American independence had been recognized; and today they add up to £12 400 000, a sum that almost equals that of the totality of England’s exports to its forty-five colonies, since that totality did not exceed £13 200 000 in 1842. – Indeed, it is difficult to see why the exchange of iron for cotton, or of cloth for flour should no longer take place between the two countries. Could it be because the citizens of the United States are now governed by a president of their choice instead of a Lord Lieutenant remunerated by the Exchequer? But what have those circumstances to do with trade? And if ever we were to appoint our own mayors and prefects, would that prevent Bordeaux wines from going to *Elbeuf and cloth made in Elbeuf from coming to Bordeaux?

Some people might say that, since the Declaration of Independence, England and the United States have mutually rejected each other’s products, which would not have happened if the colonial bond had not been severed. But those who raise that objection no doubt mean to present an argument in favor of my theory; they mean to suggest that both countries would have gained by freely exchanging the products of their soil and of their industry. May I ask why bartering wheat for iron or tobacco for cloth can be harmful according to whether the two nations who carry out the exchange are or are not politically independent of one another? – If the two great Anglo-Saxon families are acting wisely and in keeping with their true interests, in restricting exchanges between themselves, it must be because those exchanges are detrimental; and, in that case, they would also have done well to restrict them were an English Governor still in residence at the Capitol. – If, on the other hand, they acted unwisely, it means they were mistaken, it means they wrongly understood their interests, and it is difficult to see how the colonial bond could have rendered them more clear-sighted.

You should further note that the 1776 exports amounting to £1 300 000 cannot be assumed to have given England more than 20 per cent, or £260 000, profit; and is one to imagine that administering such a vast continent did not use up ten times that amount?

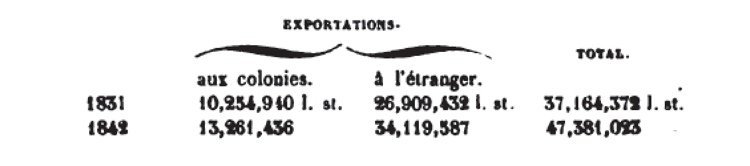

Besides, people overestimate the trade carried out by England with its colonies and especially the development of that trade. In spite of the fact that the English government compels its citizens to purchase their supplies from the colonies and settlers to purchase from the mother country, in spite of the fact that the customs barriers separating England from other nations have been prodigiously multiplied and reinforced in recent years, yet we see England’s foreign trade developing more rapidly than its colonial trade, as the following chart makes clear:

EXPORTS TOTAL

to the colonies to foreign countries

1831 £10 254 940 £26 909 432 £37 164 372

1842 £13 261 436 £34 119 577 £47 381 023

At both times, trade with the colonies only made up a little over a quarter of England’s overall trade. – The increase, over eleven years, adds up to about three million pounds. And it should be noted that the East Indies, to which the principle of free trade had been applied in the meantime, account for £1 300 000 in the increase, and Gibraltar, - which is not a source of colonial but of foreign trade, with Spain – for £600 000; which leaves a true increase in colonial trade of only £1 100 000 over a period of eleven years. During the same lapse of time, and in spite of our tariffs, exports from England to France rose from £602 688 to £3 193 939.

Thus, protected commerce progressed by 8 per cent, and impeded commerce by 450 per cent!

But if the English population did not gain, if it even lost a great deal owing to the colonial system, the same cannot be said of the younger branches of British aristocracy.

To begin with, the system requires an army, a navy, a diplomatic service, Lords Lieutenant, governors, residents, agents of all sorts and all designations. – Although it is presented as aiming to favor agriculture, trade and industry, such high offices are not, as far as I know, entrusted to farmers, merchants or manufacturers. It can be asserted that a large proportion of the heavy taxes that weigh mainly on the masses, as we have seen, is destined to pay the salary of all those agents of conquest who are none other than the younger sons of the English aristocracy.

Besides, it is a well-known fact that those noble adventurers have acquired vast estates in the colonies. They have been granted commercial protection; it is appropriate to calculate how much this costs the working classes.

Until 1825, English legislation on sugar was very complicated.

Sugar from the West Indies paid the lowest duty; sugar from Mauritius and India was subject to a higher tax. Foreign sugar was repelled by a prohibitive duty.

On July 5 1825 Mauritius was placed on an equal footing with the West Indies, as was the English part of India on August 13 1836.

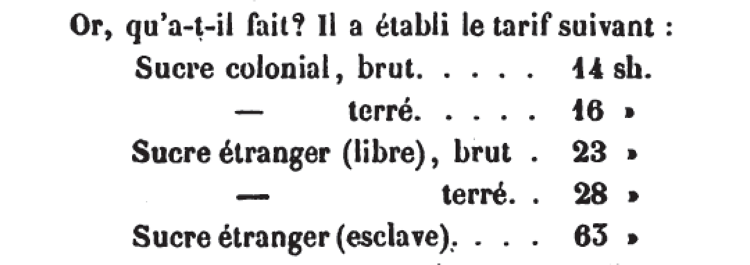

The legislation thus simplified recognized only two kinds of sugar: colonial sugar and foreign sugar. The former had to pay 24 shillings and the latter 63 shillings per hundredweight.

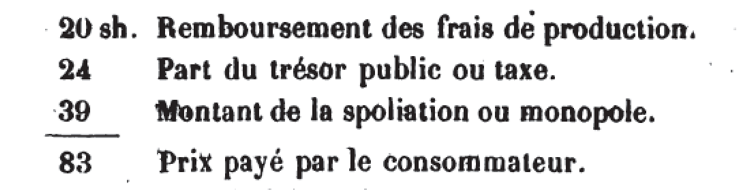

If one assumes, just for a moment, that the cost price is the same in the colonies and abroad, for example 20 shillings, the consequences of such legislation, be it for producers or for consumers, will be easily understood.

The foreign producer will not be able to present his products on the English market at less than83 shillings, that is: 20 shillings to cover production costs, and 63 shillings to meet the tax. – If colonial production happens to be insufficient to satisfy the market and if foreign sugar happens to be offered for sale, the market price (for there can be but one market price) will be 83 shillings, and, for colonial sugar, that price can be broken down as follows:

20 shillings Repayment of production costs

24 shillings Share taken by the Treasury, i.e. tax

39 shillings Amount taken by theft, i.e. monopoly

83 shillings Price paid by the consumer

It is obvious that the aim of the English law was to charge the population 83 shillings for what was worth only 20, and to share out the surplus, i.e. 63 shillings, so that the Treasury’s portion was 24 and the portion going to monopoly 39 shillings.

If things had happened in that way, if the aim of the law had been achieved, then, to know the sum total of the theft carried out by the monopolists at the expense of the population, one would need only to multiply 39 shillings by the number of hundredweight of sugar consumed in England.

But, with sugar as with corn, the law failed to a certain extent. Consumption, being limited by expensiveness, did not resort to foreign sugar, and the price of 83 shillings was never reached.

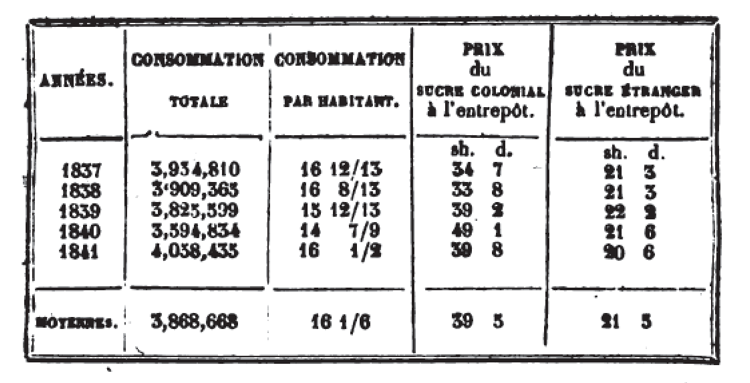

Let us leave the realm of hypotheses and look at the facts. Here they are, carefully noted down from official documents:

_________________________________________________________________________

YEARS TOTAL CONSUMPTION PRICE OF PRICE OF

CONSUMPTION PER CAPITA COLONIAL SUGAR FOREIGN SUGAR

at the warehouse at the warehouse

__________________________________________________________________________________________

shillings pence shillings pence

1837 3 954 810 16 12/13 34 7 21 3

1838 3 909 365 16 8/13 33 8 21 3

1839 3 825 599 15 12/13 36 7 22 2

1840 3 594 834 14 7/9 48 1 21 6

1841 4 058 430 15 ½ 38 8 20 6

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Averages 3 868 668 16 1/6 39 5 21 5

From the above chart, it is very easy to deduce the enormous losses inflicted by monopoly, either on the Exchequer, or on the English consumer.

Let us work it out in French currency and in round figures to make it easier for the reader to understand.

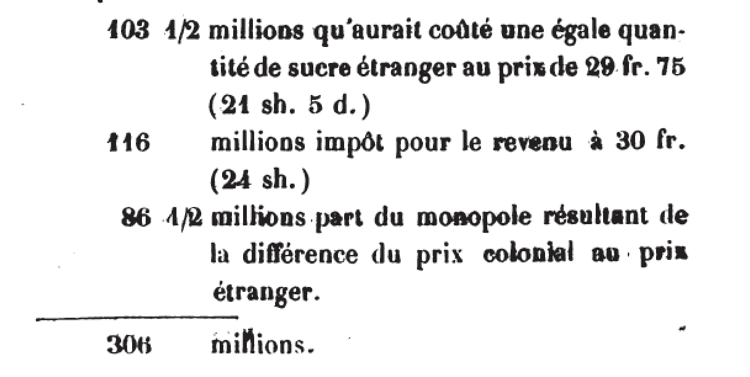

At the rate of 49 francs 20 centimes (39 shillings 5 pence), plus 30 francs’ duty (24 shillings), the average annual consumption of 3 868 000 hundredweight of sugar cost the English population the sum of 306 and a half million francs, which can be broken down as follows:

103 ½ million francs the price that an equal quantity of foreign sugar would have cost at a rate of 26.75 francs (21 shillings 5 pence)

116 million francs duty for the Inland Revenue at a rate of 30 francs (24 shillings)

86 ½ million francs share gained by the monopolists as a result of the difference between the colonial and foreign price

__________________

306 million francs

Quite clearly, under a system of equality and with a uniform duty of 30 francs per hundredweight, had the English population wanted to spend 306 million francs on that kind of consumption, for the price of 26.75 francs plus 30 francs’ duty, it could have had 5 400 000 hundredweight, or 22 kilos per person instead of 16. – On that assumption, the Treasury would have collected 162 million francs instead of 116.

Had the population contented itself with its present level of consumption, it would have saved 86 million francs per year, which would have afforded it other pleasures and opened up new outlets for its industry.

Similar calculations, which we shall spare the reader, show that the monopoly granted to forest owners in Canada costs the working classes of Great Britain, irrespective of duty, an extra 30 million.

The coffee monopoly imposes on them a surcharge of 6 500 000 francs.

Thus, on only three commodities from the colonies, over and above the natural price of the goods together with duty, a sum of 123 million francs is purely and simply taken from the consumer’s purse and paid into the pockets of the colonists, without any compensation.

I will end this dissertation, which is already too long, by quoting Mr. Porter, a member of the Board of Trade:

“In 1840, without taking into account import duty, we paid 5 million pounds more than any other nation would have paid for an equal quantity of sugar. In the same year, we exported £4 000 000’s worth to the sugar colonies ; so that we would have gained 1 million pounds by following the true principle, which is to buy on the most advantageous market, even if we had donated to the planters all the merchandise that they bought from us.”

As early as 1827, Mr. Charles Comte had had an intuition of what Mr. Porter demonstrates with figures, when he said: “If the English calculated how much merchandise they have to sell to the slave-owners in order to recover what they spend with a view to securing the latter’s custom, they would soon be convinced that the best thing to do would be to deliver their merchandise to them for nothing and thereby purchase freedom of trade.”

It seems to me that we are now in a position to appreciate the degree of freedom enjoyed by work and exchange in England, and to judge whether it is indeed to that country that one should go in order to observe the disastrous effects of open competition on the fair distribution of wealth and on equality of condition.

Let us recapitulate, and briefly sum up the facts that we have just established.

1° The elder branches of English aristocracy own the entire surface of the country.

2° Land tax has remained unchanged for one hundred and fifty years, although income from land has increased sevenfold. That tax accounts for only one twenty-fifth of public revenue.

3° Real estate is free of inheritance duty, although personal property is subject to it.

4° Indirect taxes weigh far less heavily on goods of superior quality, accessible to the rich, than on the same goods of inferior quality, available for the masses.

5° By means of the Corn Laws, those same elder branches levy a tax on the food of the masses that the best authorities set at one billion francs.

6° The colonial system, pursued on a very large scale, requires heavy taxation; and those taxes, paid almost entirely by the working classes, are also almost entirely the heritage of the younger branches of the idle classes.

7° Local taxes, such as tithes, also benefit those younger branches via the established Church.

8° If the colonial system demands the large scale setting up of armed forces, maintaining those forces in turn needs the colonial regime, and that regime leads to the monopoly system. As we have seen, on only three items, monopoly causes the English population a dead loss of 123 million francs.

I felt in duty bound to dwell at some length on setting out the above facts because they appear to me fit to dispel many a misapprehension, many a prejudice, many a blind bias. How many solutions, as obvious as they are unexpected, do they not offer to economists as well as to politicians?

And first of all, how could those modern schools of thought, who seem intent on drawing France into that system of mutual spoliation, by making the country fearful of competition, I repeat, how could those schools persist in upholding that it was freedom that gave rise to pauperism in England? Say rather that it was the result of exploitation, of organized, systematic, persistent, pitiless exploitation. Isn’t that all at once a simpler, truer and more satisfactory explanation? What! Freedom leads to pauperism! So competition, free dealing, the right to exchange property that one has a right to destroy, entail an unfair distribution of wealth? Then the law of Providence must indeed be iniquitous! So we should hasten to replace it by some human law, and what a law! A law of restriction and prevention. Instead of allowing people to act, we should prevent them from acting; instead of allowing things to pass, we should prevent them from passing; instead of allowing people to exchange, we should prevent them from exchanging; instead of leaving the remuneration for work with the person who has actually done the job, we should hand it over to someone who has done nothing! So it is only on that condition that inequality of fortune between men can be avoided! “Yes”, you used to say, “Experience has shown that freedom and pauperism coexist in England.” But you will no longer be able to say so. Freedom and destitution are far from being in a relationship of cause to effect, in fact the former, freedom, does not even exist there. People are indeed free to work there, but not to enjoy the fruits of their labor. What do coexist in England are a small number of exploiters and a large number of exploited beings; and there is no need to be a great economist to deduce that the former live in opulence and the latter in extreme poverty.

Then, if you have grasped the overall situation of Great Britain, as I have just depicted it, and the feudal spirit that presides over its economic institutions, you will be convinced that the finance and customs reform at present being implemented in that country is a matter affecting Europe and mankind in general, as well as England. It does not only involve a change in the distribution of wealth within the United Kingdom, but also a profound transformation in the country’s action abroad. Together with the unjust privileges of British aristocracy, the policies for which England has been reproached so much will obviously collapse, as will its colonial system, and its encroachments, and its armies, and its navy, and its diplomacy, in so far as they are oppressive and dangerous for mankind.

Such is the glorious triumph to which the League aspires when it demands “the total, immediate and unconditional abolition of all monopolies, of any protective duties whatsoever in favor of agriculture, industry, trade and navigation, in short absolute freedom of exchange

I will say but little here about that influential association. The spirit that drives it, its beginnings, its progress, its work, its struggles, its setbacks, its successes, its aims, its means of action, all will appear, full of movement and life, later in this book. There is no need for me to minutely describe that great organism, since I will show it breathing and acting before the French public, from whose eyes, by some incomprehensible miracle of ingenuity, the subsidized monopolistic press has kept it hidden for so long.

In the midst of the distress that the regime we have just described could not fail to inflict on the working classes, seven men met in Manchester in October 1838, and, with the manly determination characteristic of the Anglo-Saxon race, resolved to overthrow all monopolies by lawful means, and to bring about, without unrest, without bloodshed, and through the sole power of public opinion, a revolution as profound, more profound perhaps than that accomplished by our fore-fathers in 1789.

To be sure, it required more than ordinary courage to face up to such an undertaking. The opponents that they were to combat had on their side wealth, influence, the legislature, the Church, the State, the Treasury, land, offices, monopolies, and were moreover surrounded by traditional respect and reverence.

And where were they to find support against such an imposing combination of forces? Amongst the productive classes? Alas! In England as in France, each sector of production believes its existence to be bound up with some shred of monopoly. Protectionism has imperceptibly spread to all sectors. How can one make people prefer remote and apparently uncertain interests to immediate and positive ones? How can one dispel all those prejudices, all those sophisms that time and egoism have so deeply ingrained in people’s minds? And supposing one does manage to enlighten public opinion in all ranks and classes, already no mean task, how can one instill into it enough energy, perseverance and joint action to enable it to become, via the polls, master of the legislature?

The prospect of such difficulties did not frighten the founders of the League. Having honestly considered and assessed them, they felt strong enough to overcome them. The agitation was decided on.

Manchester was the birthplace of that great movement. It was natural that it should arise in the north of England, amidst the industrial population, just as it would be natural for it to arise one day within the rural population of southern France. Indeed, in both countries the activities that offer means of exchange are those that suffer most immediately from prohibition, and it is obvious that if they were free, the English would send us iron, coal, machinery, cloth, in short, products from their mines and factories, which we would pay for with cereals, silk, wine, oil, fruit, that is, with products from our agriculture.

That explains to some extent the apparently curious name adopted by the association: Anti-Corn Law League. Since that limited denomination probably contributed in no small measure to diverting the attention of Europe from the significance of the agitation, we consider it essential to record below the reasons why it was adopted.

The French press has rarely spoken of the League (we shall explain why elsewhere), and when it has been unable to do otherwise, it has at any rate taken care to refer to the term: Anti-Corn Law, in order to insinuate that it was to do with a most particular question, with the mere reform of the law regulating the conditions for importing cereals into England.

But such is not the only object of the League. It aspires to the entire and utter eradication of all privileges and all monopolies, to absolute freedom of trade, to unlimited competition, all of which implies the downfall of aristocratic preponderance in so far as it is unjust, and the dissolution of colonial bonds in so far as they are exclusive, that is to say a complete revolution in the domestic and foreign policies of Great Britain.

And to give just one example: today we see the free-traders siding with the United States on the subject of Oregon and Texas. Indeed, what does it matter to them that those territories administer themselves under the protection of the Union, instead of being governed by a Mexican president or by an English lord-commissioner, so long as everyone can sell, buy, acquire and work there; so long as any honest transaction can freely take place there? Under those conditions they would further willingly hand over to the United States both parts of Canada and Nova Scotia, and the West Indies into the bargain; they would even hand them over unconditionally, fully confident that freedom of exchange will sooner or later be the rule in international transactions.(note de Bastiat – rechercher original du discours de Fox)

But it is easy to understand why the free-traders began by uniting all their forces against a single monopoly, the cereal monopoly: because it is the keystone of the whole system. It is the share of the aristocracy, the special portion that the legislators have appropriated. Let that monopoly be torn from them, and they will make little of all the others.

Besides, it is the monopoly that weighs most heavily on the population, and whose iniquity can most easily be demonstrated. Tax on bread! on food! on life! To be sure, that is a rallying cry wonderfully suited to arousing the sympathy of the masses.

It is certainly a great and stirring sight to see a small number of men striving, by dint of hard work, perseverance and energy, to destroy the most oppressive and most solidly organized regime, after slavery, that has ever weighed on a great nation and on mankind as a whole; and to do so without resorting to brutal force, without even seeking to unleash public censure, but by shedding light on all the innermost parts of the system, by refuting all the sophisms on which it rests, by instilling into the masses the knowledge and the virtues which alone can free them from the yoke that is crushing them.

But the sight becomes even more impressive when one sees the immense battlefield expanding daily with the number of questions and interests that keep coming, one after another, to take part in the struggle.

To begin with, the aristocracy did not deign to enter the lists. When it saw itself master of political power through the ownership of land, of physical power through the army and navy, of moral power through the Church, of legislative power through Parliament, and finally, of the power that is worth all the others, the power of public opinion, through that false national greatness that flatters the population and seems bound up with the institutions under attack; when it contemplated the height, thickness and cohesion of the fortifications in which it had entrenched itself; when it compared its forces with those that a few isolated men were directing against it, - it believed it could withdraw into silence and disdain.

And yet the League progressed. While the aristocracy had on its side the established Church, the League turned to all the dissenting churches for help. The latter are not dependent on monopoly through tithes, they are supported by voluntary gifts, that is to say by the confidence of the public. They understood early on that the exploitation of man by man, be it called slavery or protection, is contrary to Christian principles. Sixteen hundred dissenting ministers answered the League’s call. Seven hundred of them, hastening from all points of the kingdom, gathered in Manchester. They discussed; and the outcome of their discussion was that they would go all over England preaching the cause of free trade as being consistent with the laws of Providence that it was their mission to promulgate.

While the aristocracy had on its side landed property and the farming classes, the League counted on such property as physical ability, skills and intelligence. Nothing equals the eagerness with which the manufacturing classes hastened to cooperate in the grand task. Spontaneous subscriptions contributed 200 000 francs to the League’s fund in 1841, 600 000 francs in 1842, one million in 1843, two million in 1844; and in 1845 twice, maybe three times that sum would be devoted to one of the objectives that the association had in view: the registration of a large number of free-traders as candidates on the electoral lists. Among the occurrences linked to the above subscription, one in particular made a great impression on people’s minds. The list initiated in Manchester on November 14 1844 showed takings of £16 000 sterling (400 000 francs) by the end of that same day. Thanks to those abundant resources, the League drew up its doctrines in the most varied and understandable form and distributed them amongst the population in countless brochures, pamphlets, posters and newspapers; it divided England into twelve districts, in each of which it supported a professor in economics. The League itself, like a mobile university, held its sessions in public in all the towns and counties of Great Britain. It seems moreover that He who controls human affairs provided the League with unexpected means of success. The postal reform enabled it to carry on a correspondence of over 300 000 dispatches annually with the election committees it had set up throughout the country; the railways imparted to its movements a ubiquitous character, and one saw the same men who had agitated in Liverpool in the morning, agitating in Edinburgh or Glasgow in the evening; finally, the electoral reform had opened the doors of Parliament to the middle class, and the founders of the League, Cobden, Bright, Gibson, Villiers and the like, were authorized to combat monopoly, face to face with the monopolists and within the very precinct where the system had been decreed. They entered the House of Commons and formed a party, if one can call it so, quite apart from the Whigs and Tories, and which had no precedents in the history of constitutional nations, a party determined never to sacrifice absolute truth, absolute justice, absolute principles to personal considerations, to the scheming and strategies of ministries and opposition parties.

But it was not enough to win over the social classes on whom monopoly weighed directly; they had further to undeceive those classes who sincerely believed their wellbeing and even their existence to depend on protectionism. Mr. Cobden undertook that arduous and perilous task. Within only two months, he caused forty meetings to take place amidst the farming population itself. There, often surrounded by thousands of laborers and farmers, into whose midst one can imagine many a troublemaker had slipped at the instigation of those whose interests were threatened, he displayed a degree of courage, composure, ingenuity and eloquence that aroused surprise, maybe even sympathy, among his most ardent opponents. Placed in a position similar to that of a Frenchman setting out to preach the doctrine of free trade at the Decazeville forges or amongst the Anzin miners, it is difficult to say what is most to be admired in that outstanding man, all at once an economist, an orator, a statesman, a tactician, a theorist, and to whom I think one can aptly apply what was said of *Destutt de Tracy: “Through sheer good sense, he attains genius” His efforts received the reward they deserved, and the aristocracy was pained to see the principle of liberty rapidly gaining ground amongst the population dedicated to agriculture.

So the time had past when the aristocracy would drape itself in its contemptuous arrogance; it had finally emerged from its inertia. It attempted to resume the offensive, and its first maneuver was to slander the League and its founders. It scrutinized their public and private lives; but, in the realm of character it was soon forced to abandon the battlefield, where it risked leaving more dead and wounded than the League. It then called to its aid the army of sophisms that, at all times and in all countries, have served as buttresses to monopoly. Protection for agriculture, invasion of foreign products, fall in salaries as a result of the abundance of provisions, national independence, metallic currency running out, colonial outlets guaranteed, political domination, empire of the seas; such were the subjects under debate, no longer among scholars, no longer between one school of thought and another, but before the people, between democracy and aristocracy.

However, it so happened that the League members were not only courageous agitators; they were also sound economists. Not one of those many sophisms withstood the blow of discussion; and, where necessary, parliamentary inquiries called for by the League were able to demonstrate their inanity.

The aristocracy then adopted another course of action. Destitution was rife, profound, horrifying, and its cause was obvious -–it was because a hateful inequality presided over the distribution of social wealth. But against the League’s flag which bore the word JUSTICE, the aristocracy set a banner on which one could read the word CHARITY. They no longer questioned the sufferings of the population; but they relied on a powerful means of diversion: alms-giving. “You are suffering”, they said to the people, “that is because you have over-multiplied, so we will set up a vast emigration system for you” (Mr. Butler’s motion) – “You are dying of hunger; we will give each family a garden and a cow” (Allotments) – “You are weak from exhaustion; that is because too much labor is demanded of you, so we will limit working hours” (Bill on the ten-hour day). Then came subscriptions to offer the poor classes free public baths, recreation centers, the benefits of a national education system, etc. Always charity, always palliative measures; but as for the cause that made them necessary, as for monopoly, as for the artificial and unfair distribution of wealth, there was no mention of touching them.

Here the League had to defend itself against a system of aggression that was all the more perfidious as it appeared to attribute to the League’s opponents, amongst other monopolies, the monopoly of philanthropy, and to place the League itself in the sphere of strict and cold justice, which is much less fit than charity, however powerless, however hypocritical, to arouse the unconsidered gratitude of the suffering.

I will not reproduce the objections that the League raised against all those projects of supposedly charitable institutions; some of them will appear in the course of this book. Suffice it to say that the League gave its support to those charitable organizations that were of an indisputably useful nature. Thus, amongst the free-traders of Manchester, nearly one million was collected in order to give space, air and daylight to the districts inhabited by the working classes. In the same town, an equal sum, also proceeding from voluntary subscriptions, was devoted to building schools. But at the same time, the League never tired of pointing out the trap hidden under that ostentatious show of philanthropy: “When the English population is dying of hunger”, the League would say, “it is not sufficient to say to it: We will transport you to America where food is abundant. That food must be allowed to enter England. – It is not sufficient to give working-class families a garden so they can grow potatoes. Above all, they must not be robbed of part of the profits that would obtain them more substantial nourishment. – It is not sufficient to limit the excess of work to which exploitation condemns them. Exploitation itself must be stopped, so that ten hours’ work are worth twelve. – It is not sufficient to give them air and water, they must be given bread, or at least the right to buy bread. It is not philanthropy, but liberty that must be set against oppression; it is not charity, but justice that can heal the ills of injustice. Alms-giving has, and can have, only an insufficient, transitory, uncertain and often degrading effect.”

Having run out of sophisms, excuses and time-wasting pretexts, the aristocracy still had one resource left: the majority in Parliament, the majority that exempts you from being right. The final act in the agitation had therefore to take place within the electoral bodies. After popularizing healthy economic doctrines, the League had to give a practical direction to the individual efforts of its countless converts. To profoundly modify the constituencies, the electorate of the kingdom, to undermine the influence of the aristocracy, to draw upon corruption the retribution of the law and of public opinion: such was the new phase into which the agitation entered, with a degree of energy that seemed to increase as progress was made. Vires acquirit eundo. At the call of Cobden, Bright and their friends, thousands of free-traders got themselves registered on the polling lists, while thousands of monopolists were struck off, and, judging by the speed of this evolution, one can anticipate the day when the House will no longer represent a class, but the community.

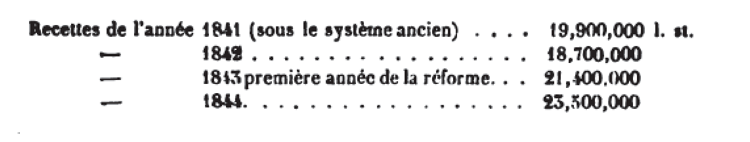

You may ask whether so much work, so much zeal, so much devotion to duty have so far remained without influence on the course of public affairs, and whether the progress of liberal doctrines in the country has not been reflected to some degree in the legislation.

At the outset, I described the economic system as it was in England before the commercial crisis that gave birth to the League; I even tried to calculate a few instances of the extortion that the ruling classes exerted on the enslaved classes through the dual mechanism of taxation and monopoly.

Since that time, both taxation and monopoly have been modified. Who has not heard of the financial plan that Sir Robert Peel has just presented to the House of Commons, a plan that is but the development of reforms initiated in 1842 and 1844, and whose full implementation is reserved for subsequent sessions of Parliament? I sincerely believe that the spirit of those reforms has been misunderstood in France, and that their significance has by turns been exaggerated or belittled. So you will forgive me if I now enter into some detail; I shall nevertheless endeavor to be as brief as possible.

Exploitation (I beg to be forgiven for the frequent recurrence of the term; but it is necessary in order to put an end to the gross error that is implied in its synonym: protectionism), exploitation, reduced to a system of government, had produced all its natural consequences: extreme inequality in means; destitution, crime and disorder within the lowest social strata; an enormous fall in all forms of consumption, and consequently a reduction in public revenue and a deficit which, increasing year by year, threatened to undermine the credit of Great Britain. Obviously, it was not possible to remain in a situation that threatened to sink the ship of the State. Troubles in Ireland, Agitation in trade, Arson in rural districts, the “Rebecca” riots in Wales, the Chartist movement in manufacturing towns, those were but the various symptoms of a single phenomenon, the suffering of the population. But the suffering of the population, that is, of the masses, that is to say, of almost the whole of mankind, must at length affect all classes of society. When the population has nothing, it buys nothing; when it buys nothing, factories grind to a halt, and farmers cannot sell their harvest; and if they do not sell, they cannot pay their farm rent. Thus, even the great law-making lords found themselves, by the very effect of their law, caught between the bankruptcy of the farmers and the bankruptcy of the State, and threatened both in their landed and personal property. Thus the aristocracy felt the ground shaking under its feet. One of its most distinguished members, Sir James Graham, at present Home Secretary, had written a book to warn the aristocracy of the dangers surrounding it: “If you do not give a part, you will lose all,” he said, “and a revolutionary storm will sweep away from the surface of the land not only your monopolies, but your honors, your privileges, your influence and your ill-acquired wealth.”

The first expedient that presented itself to guard against the most immediate danger, the deficit, was, as the expression also in use among our own statesmen has it, to demand from taxation all that it can yield. But it so happened that the very taxes that they tried to increase were those that proved most insufficient for the Treasury. They were forced to give up that resource for a long time, and the present Cabinet’s first concern on coming to power was to declare that taxation had reached its uttermost limit: “I am bound to say that the people of this country has been brought to the utmost limit of taxation” (Peel’s speech of May 10, 1842)

With a little insight into the respective situations of the two large groups whose interests and struggles I have described, it will be easy to understand the nature of the problem each of them had to solve.

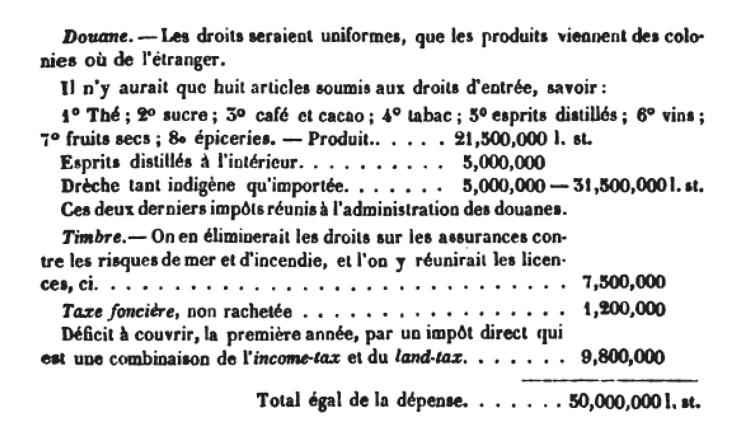

For the free-traders, the solution was very simple: it was to abolish all monopolies. To free imports from duty necessarily meant increasing exchanges and consequently exports; it therefore meant the population would be given bread and work all at once; furthermore, it meant one would favor all forms of consumption, consequently indirect taxes, and ultimately restore the financial balance.

For the monopolists, the problem was insoluble so to speak. It was a matter of unburdening the population without shielding it from the monopolies, of increasing public revenue without putting up taxes, and of preserving the colonial system without increasing national expenditure.

The Whig cabinet (Russell, Morpeth, Melbourne, Baring, etc.) presented a plan that stood between the two solutions. It weakened both the monopolies and the colonial system, without destroying them. The plan was accepted neither by the monopolists nor by the free-traders. The former wanted absolute monopoly, the latter unlimited freedom. The former exclaimed, “No concessions!”, and the others, “No negotiations!”

Defeated in Parliament, the Whigs turned to the electorate. The latter decided overwhelmingly in favor of the Tories, that is, in favor of protection and of the colonies. The Peel ministry was set up (1841) with the explicit task of discovering the undiscoverable solution (to which I was referring earlier) to the vast and terrible problem set by the deficit and the destitution of the population; and it must be acknowledged that it has overcome the difficulty with remarkable sagacity in conceiving and energy in implementing its plan.

I will try to explain Mr. Peel’s financial plan, at least as I understand it.

We must not lose sight of the fact that, considering the Party that supported him, that Statesman had to bear several aims in view:

1° To restore the financial balance;

2° To unburden consumers;

3° To put new life into commerce and industry;

4° To preserve as far as possible, that essentially aristocratic monopoly, the corn monopoly;

One may also imagine that that eminent man, who better than any other knows how to interpret the signs of the times, and who sees the philosophy of the League spreading throughout England in great strides, also harbors deep in his soul a personal but glorious project: that of earning for himself the support of the free-traders for the day when they gain the majority, so that, with his own hand, he can set the seal of completion on the achievement of free trade, without allowing any name other than his to be officially attached to the greatest revolution in modern times.

There is not one of Sir Robert Peel’s measures, not one of his words, that fails to satisfy the immediate or far-off conditions of that project. You will judge for yourselves.

The pivot around which all the financial and economic developments we have yet to speak of revolve is income tax.

Income tax, as you know, is a subsidy levied on all forms of income. It is essentially a temporary and patriotic tax. It is only resorted to in the most serious circumstances and until now, in case of war. In 1842, Sir Robert Peel persuaded Parliament to authorize income tax for three years; it has just been extended until 1849. This is the first time that, instead of being used for destructive purposes and to inflict the evils of war on mankind, it has become the instrument for those useful reforms that the nations who wish to take advantage of the blessings of peace are trying to carry out.

It is fitting to point out here that all revenues under £150 (3 700 francs) are exempt from income tax, so that it is only imposed on the wealthy class. It has often been said, on this side of the Channel as well as on the other, that income-tax was a permanent article in England’s financial code. But anyone who is aware of the nature of that tax and of the way in which it is levied, knows very well that it could not be established permanently, at least in its present form; and if the Cabinet harbors some ulterior motive in the matter, one may legitimately believe that, by accustoming the well-to-do classes to contributing in a greater measure to public expenses, the government is thinking of putting land-tax in Great Britain more in harmony with the needs of the State and the requirements of fair distributive justice.

Whatever the case may be, the first aim that the Tory ministry had in view, to restore the financial balance, was achieved thanks to the resources of income-tax; and the deficit that was threatening England’s credit has disappeared, at least for the time being.

A surplus in receipts was even forecast as early as 1842. This was to be devoted to the second and third items on the schedule: unburdening consumers; putting new life into commerce and industry.

Here we enter into the long series of customs reforms carried out in 1842, 1843, 1844 and 1845. Our intention cannot be to describe them in detail; we must limit ourselves to making known the spirit in which they were devised.