Liberty Matters

How Much Freedom Did America Gain When It Revolted?

Messrs. Geloso and Noël have written a thought-provoking paper that raises serious questions about the nature of historical causation and how historians can know the past. I shall focus my remarks less on their substantive economic claims and more on the methodological assumptions informing their paper.

Messrs. Geloso and Noël have written a thought-provoking paper that raises serious questions about the nature of historical causation and how historians can know the past. I shall focus my remarks less on their substantive economic claims and more on the methodological assumptions informing their paper.The title of the Geloso-Noël paper asks a provocative question: How much economic growth did America leave behind when it revolted? Scholars of the period have some sense of this. Economic historians have measured the Americans’ short-term economic losses during the years of the imperial crisis (1765-1776), during the war for independence (1776-1781), and during years immediately following the Battle of Yorktown up to ratification of the U.S. Constitution (1783-1788), but it is difficult to demonstrate a causal connection beyond that because, in part, the American economy quickly made up for its wartime losses and launched an unprecedented era of wealth production.

Geloso and Noël then course correct to pursue a slightly different question. The question they now seek to answer seems to be: how much wealth was generated by the American Revolution? In their opening paragraph, Geloso and Noël engage with certain (unnamed) scholars who claim there is a causal connection between twenty-first century American wealth and the American Revolution. Our two authors believe such claims require a “leap of faith,” although they never explain the nature of these alleged leaps of faith or why they are inadequate to understanding the causal relationship between the American Revolution and twenty-first century American wealth.

Ironically, Geloso and Noël then ask their readers to take an even bigger leap of faith. They invite us to join them on a thought experiment, namely, to “conjure a counterfactual in which America remained a British colony or became independent in ways similar to later British Dominions [emphasis mine],” such as Canada. From here, Geloso and Noël deductively “construct a theory” against which they will measure its validity by seeing if it “hold[s] up using both quantitative and qualitative sources.” Alternatively, they might have used an inductive approach that begins with empirical data to construct a theory.

Be that as it may, Geloso and Noël sharpen their counterfactual by imagining a scenario in which the American colonists lose the war for independence. To be clear, they are not asking us to consider how the American economy might have developed had there been no Declaration of Independence, war, or revolution, but instead they want us to think about how the economy might have developed had the Americans lost the war. To this conjured counterfactual, Geloso and Noël add a second counterfactual, which compares American economic development with that of the French-Canadian province of Quebec, which came under British rule at the end of the Seven Years’ War.

Our two authors then ask the reader to compare the primary counterfactual to the corollary counterfactual, namely, to compare a “defeated” America to the neutral province of Quebec, which took no part in the war despite an invitation from the Americans to join them in the fight for independence. In other words, the second counterfactual (i.e., the example of Quebec) serves as an example of the kind of counterfactual that the authors explicitly rejected in the first instance (i.e., an America that does not declare independence and stays in the British empire). Is this not comparing apples to oranges?

The obvious problem with our authors’ primary counterfactual is that we are no longer dealing with historical reality. We have entered the realm of speculation and guesswork, where imperfect knowledge reigns supreme and uncertain.

For example, the Geloso-Noël counterfactual does not consider the real possibility—indeed, the likelihood—that a victorious Britain would have sought revenge and imposed harsh penalties on the colonies. Had the British won the war, they almost certainly would have extended and deepened the role of the British State in the colonies. It is not unreasonable to think that Parliament and Whitehall would have moved more Redcoats, tax collectors and other customs officials to the colonies. They would have almost certainly raised taxes and created new regulations on both external and internal trade. It is also likely that George III would have destroyed the colonial charters, suspended or abolished the colonial legislatures, and converted the colonies to royal protectorates governed by royally appointed governors. The trans-Appalachian West would have been closed to the colonists. (Imagine how the trajectory of subsequent American economic development would have changed had the Americans been prevented from settling and developing the West.) And all this would have been likely just the beginning of the repressive measures taken against the colonies by the British Deep State.

There is no point in using a counterfactual if you can’t know or control for the externalities that, in this case, would have likely come with a British victory over the colonies.

And once the counterfactual “what if” door has been opened, why not go further, and ask: What if Great Britain had lost the Seven Years’ War? What if Great Britain had never launched its campaign to tax and regulate the colonies? What if the colonies had accepted all of Britain’s taxes and regulations? And what if Great Britain had acceded to the colonists’ demands? And on and on we could go!

To complicate matters even more, Geloso and Noël eventually announce that the primary counterfactual in which the Americans lose the war for independence “is the wrong counterfactual” because “it falls into the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy.” Yes, but why put the reader through this if it’s the wrong counterfactual?

I also wish the authors had explained more clearly how and why using the Quebec counterfactual is helpful in comparing it to the counterfactual of a defeated America. Why not compare Quebec with an imaginary America that agrees to stay in the British Empire? Or why not just compare Quebec with the historically real America that emerged out of a successful war against Great Britain?

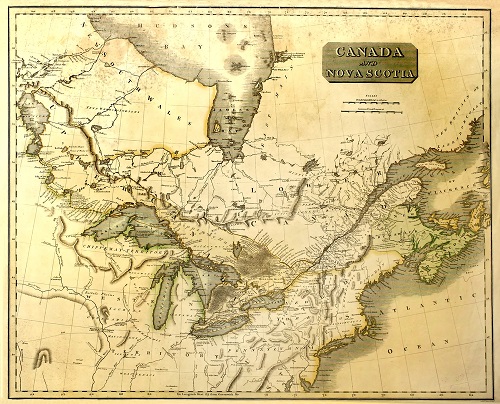

Or, better yet, why not use Nova Scotia or Upper Canada (i.e., Ontario) as the counterfactual? The problem with using Quebec is that it was too different politically, culturally, religiously, legally, and even economically from the United States to serve as helpful counterfactual. Nova Scotia or Upper Canada were much closer in these ways to the United States, and thus the comparison with these two provinces would have been measuring apples to apples.

In the end, the ultimate point of the Geloso-Noël paper was unclear to me. They conclude by claiming that they view their paper as “a vindication of the American Revolution,” but I fail to see how that is so. To vindicate the Revolution in economic terms would be to demonstrate how the Revolution changed the American economy (which it did) and what the consequences were of that change. Regrettably, this paper does not do that.

I, therefore, urge Messrs. Geloso and Noël to address much simpler and more direct questions, such as: What was the causal effect of the American revolution on subsequent economic growth? How and why did the American Revolution change the nature of the American economy? And finally, did the American Revolution cause the United States to grow faster than its neighbors?

A Reality-Based Approach

I am what might be called an “old-fashioned” scholar, which means I prefer a reality-based approach to historical questions. A reality-based approach to history attempts to explain what happened, how and why it happened, what its consequences were, and what its meaning is for the present and future. I take my Scotch neat, and I like my history straight up.

The real, non-counterfactual question that I believe Messrs. Geloso and Noël could and should have addressed is simple and direct: What did the political Revolution of 1776 do to launch an economic revolution over the course of the next century?

To answer this question, we might begin by recalling that in 1763, Britain’s American colonists were the freest and possibly the wealthiest people anywhere in the world (including relative to their cousins in Great Britain), but they were free largely because of Britain’s policy of “salutary neglect” and their distance from the mother country. The colonies were out of sight from British imperial officials, which means they were also out of mind.

All of that changed with the end of the Seven Years’ War and with the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765, followed in quick succession by the Declaratory (1766), Townshend (1767-68), Tea (1773), Intolerable (1774), and the Prohibitory (1775) Acts. In a remarkably short period of time, the British Deep State attempted to reassert its political and economic control over the colonies by taxing and regulating them in unprecedented ways. Who knows what they might have done if they had defeated the Americans on the battlefield?

Once independence was declared, the former colonists began to create a new kind of society unlike any other. First, at the state level, they created new constitutions, which in turn created new governments, and then they created a federal constitution and a national government for the United States. The Americans created what I have called laissez-faire constitutions that in turn created laissez-faire governments.

Relative to all governments hitherto, these new American governments were dramatically limited in their purposes and powers, which means they created large spheres of liberty, or what Adam Smith referred to as “the natural system of perfect liberty and justice.” The result was a remarkable explosion of human energy and entrepreneurial activity in the six decades after the founding. Millions of ordinary men, once limited in what they could do and earn, were liberated from the political and social system of an archaic past to secure for themselves a place in the world determined by their merit. American revolutionaries wanted to create a new republican world defined and led by those whom John Adams and Thomas Jefferson referred to as the “natural aristocracy.” Birth and blood were to be replaced by talent and ability, and aristocracy was to be replaced by meritocracy.

The greatness of the American Revolution was to remove the artificial barriers that had suppressed the natural talents of ordinary people. All over the United States the natural aristocracy of ability and ambition was set free from their expected roles to see where their aspirations and dreams might take them. The legitimacy of the various forms of traditional political, social, economic, religious, and familial authority was coming apart. The social duties and responsibilities of all Americans were being reordered. The distinction between superiors and subordinates was unravelling, and new men were pushing their way through old barriers and limitations.

The explosion in creativity and productivity that came out of the American Revolution was unprecedented in world history. This is the story that I would like to see Geloso and Noël tell.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.