Liberty Matters

Lincoln on Natural Rights and Abolition

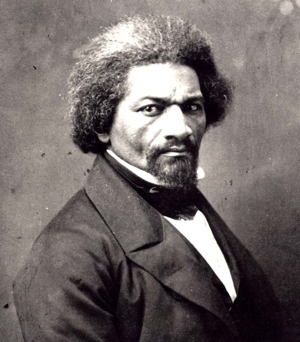

I had intended in this post to return to the subject of Douglass and John Brown, a further discussion of which I promised in my first post. In the meantime, however, George Smith has taken exception to my high ranking of Lincoln as an apostle of natural rights and has enlisted Douglass in support of his position. These are subjects, especially the latter, that I have taken up in print previously, and I'm happy to return to them now.

I had intended in this post to return to the subject of Douglass and John Brown, a further discussion of which I promised in my first post. In the meantime, however, George Smith has taken exception to my high ranking of Lincoln as an apostle of natural rights and has enlisted Douglass in support of his position. These are subjects, especially the latter, that I have taken up in print previously, and I'm happy to return to them now.In sum: as to Lincoln's worthiness of the high ranking I assign him, I stand my ground. And as to Douglass's assessment of Lincoln, it's a complicated matter—even more complicated than Douglass himself rendered it in the Freedmen's Monument speech—but I think the evidence weighs in favor of a more laudatory view than Smith suggests.

My estimation of Lincoln as a pre-eminent 19th-century apostle of natural rights is based mainly on two considerations. First is the depth of Lincoln's conviction of the truth and the importance of the natural-rights argument, and second is the unparalleled prudence with which Lincoln advanced the natural-rights cause in American political life in the face of what was surely the gravest challenge to it in the 19th century and perhaps its gravest challenge in the whole of U.S. history.

To establish the depth of Lincoln's natural-rights conviction, it would be easy to assemble a tediously long train of quotations. A few can suffice.

As he made his way out to Washington to assume the presidency, Lincoln stopped in Philadelphia, where he said this in a speech at Independence Hall: "You have kindly suggested to me that in my hands is the task of restoring peace to our distracted country. I can say in return, sir, that all the political sentiments I entertain have been drawn, so far as I have been able to draw them, from the sentiments which originated, and were given to the world from this hall in which we stand. I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence."[86]

In an 1860 autobiographical sketch, Lincoln wrote (in third person) of his 1854 return to electoral politics: "the repeal of the Missouri Compromise aroused him as he had never been before."[87] Why was this? Lincoln supplied the answer in his 1854 speech on the subject, and he reiterated it in his 1858 debates with Stephen A. Douglas. "The spirit of seventy-six and the spirit of Nebraska, are utter antagonisms," he said in that 1854 speech. Douglas's Kansas-Nebraska Act, which effected the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, portended by that fact a repeal of the Declaration of Independence itself, which Lincoln considered to be "the sheet anchor of American republicanism," containing indeed "the very fundamental principles of civil liberty."[88]

In the first of their debates in 1858, Lincoln charged against Douglas: "when he says that the negro has nothing in the Declaration of Independence…. When he invites any people willing to have slavery, to establish it, he is blowing out the moral lights around us. [Cheers.] When he says he 'cares not whether slavery is voted down or voted up,'—that it is a sacred right of self-government—he is in my judgment penetrating the human soul and eradicating the light of reason and the love of liberty in this American people."[89]

Smith, however, bases his relatively low estimation of Lincoln not mainly on the question of Lincoln's antislavery convictions but rather on Lincoln's disapproval of abolitionism. I take it he generally agrees with abolitionists' characterization of Lincoln, as he puts it, "as an opportunist who sacrificed antislavery principles to political expediency." With due respect both to Smith and to Lincoln's abolitionist (and neo-abolitionist and libertarian) critics, I think this characterization of Lincoln is just plain wrong.

It is of course true that Lincoln disapproved of abolitionism, but it is vital—it marks the only substantial difference, as Lincoln might say—to add that the disagreement is located on grounds of prudence rather than of principle. In that contest of prudence, I think, Lincoln wins hands down.

In the course of my daily labors researching a project on Martin Luther King, Jr., serendipity brought to my attention today King's remark, approvingly quoting another: "When you are right, you cannot be too radical."[90] Something like that sentiment also animated King's forbears the radical abolitionists, including William Lloyd Garrison above all, but also, from time to time, Frederick Douglass. Lincoln, however, is in my view sensible in rejecting it. Yes, actually, even if you are right, you can be too radical. The abolitionists were both.

Of course abolitionists were right to denounce slavery as a monstrous wrong. "If slavery is not wrong," Lincoln agreed, "then nothing is wrong."[91] They were right to campaign against it. The political abolitionists whom Douglass joined after breaking with the Garrisonians were right to make it an issue in electoral politics. They were not right, however, to denounce Free-Soil Whigs, then Republicans like Lincoln, as amoral agents of expediency for espousing the non-extension rather than the immediate-abolition position. Their insistence on the latter position rendered the Liberty Party in its various iterations a hopeless electoral failure; their abolitionist purity showed itself in practice to be mere fecklessness. Lincoln's non-extension position, by contrast, got him elected to the presidency and thus positioned to become the Great Emancipator.

That was not mere expediency. It was a principled antislavery position, prudently compromised to prepare further antislavery advances. Had Lincoln actually been willing to sacrifice antislavery principles to expediency, he would have backed away from the non-extension position when southerners made clear they would secede over it; he would likewise have accepted the Crittenden Compromise in the secession winter. He refused to do such things because the only Union worth preserving to him was a Union wherein slavery remained, in the public mind, "in the course of its ultimate extinction." Similarly, as I said in a previous post, had Lincoln taken Douglass's and other abolitionists' advice to make the Civil War prematurely an abolition war, he likely would have lost the war and the antislavery cause with it.

In sum, for these reasons and others I think Lincoln stands above all American statesmen as the most articulate and effective defender of the natural-rights principles of the Declaration.

The question remains as to Frederick Douglass's judgment of Lincoln. About that I have things to say, too, but the present post has become lengthy. I'll leave it for the next installment.

Endnotes

[86.] Abraham Lincoln, "Address in Independence Hall," February 22, 1861, in Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, edited by Roy P. Basler (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2001), 577.

[87.] Lincoln, "Autobiography written for John L. Scripps," c. June 1860, Roy P. Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953-55), vol. 4, 67.

[88.] Lincoln, "Speech on the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise," October 16, 1854, Speeches and Writings,315, 304, 291.

[89.] Lincoln, "Lincoln-Douglas Debates: First Debate," August 21, 1858, 460.

[90.] Martin Luther King, Jr., Why We Can't Wait (New York: New American Library, 1963), 133.

[91.] Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864, Collected Works vol. 7, 281.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.