Liberty Matters

Austrian Capital Theory and the Role of Ideas

I’d like to discuss three topics in David Hart’s excellent and characteristically erudite essay. The first of these topics is the most general. Hart writes of wanting to study “how pro-liberty ideas were developed and then used to bring about political and economic change in a pro-liberty direction.” He proceeds to list a large number of “historical examples of successful radical change in ideas and political/economic structures, in both a pro-liberty and anti-liberty direction.”

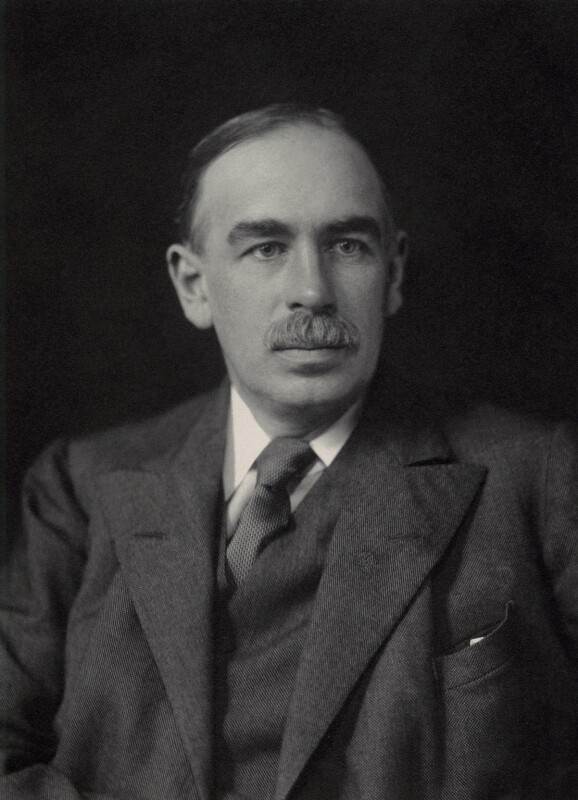

I’d like to discuss three topics in David Hart’s excellent and characteristically erudite essay. The first of these topics is the most general. Hart writes of wanting to study “how pro-liberty ideas were developed and then used to bring about political and economic change in a pro-liberty direction.” He proceeds to list a large number of “historical examples of successful radical change in ideas and political/economic structures, in both a pro-liberty and anti-liberty direction.”I hope that I do not misinterpret Hart, but his remarks suggest that he takes ideas to be a major cause, perhaps the major cause, of political and social change. This is a familiar view. Everyone will remember Keynes’s comment in The General Theory: “the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”[20]

Some people go further. Leonard Peikoff claims in The Ominous Parallels that not only do philosophical ideas determine the course of history, but that this must be the case. “Since men cannot live or act without some kind of basic guidance, the issues of philosophy in some form necessarily affect every man, in every social group and class. Most men, however, do not consider such issues in explicit terms. They absorb their ideas ... from the atmosphere around them. . .”[21]

Peikoff notes that a “cultural atmosphere is not a primary. It is created, ultimately, by a handful of men: by those whose lifework it is to deal with, originate, and propagate fundamental ideas.” Accordingly, the “root cause of Nazism” lies in the “esoteric writings” of the professors who laid the foundation for the events “hailed or cursed in headlines.”[22]

I do not wish to claim that the view I attribute to Hart of the role of ideas in history is false: to the contrary, I hope that it is true. If it is true, though, it is not obviously true, and it should not be assumed as a matter of course. Those who favor the position ought to argue for its truth, and pleasant quotations from Friedrich Hayek and Lord Acton about the importance of ideas do not suffice.

Whether or not, though, ideas are influential, the question arises: how are they created and spread? Hart appeals to “Austrian capital theory,” and his remarks about this are the next topic I’d like to discuss. What interests Hart is “in particular the notion of ‘the structure of production of goods’ -- if we understand in this context that “goods’ are ‘intellectual goods,’ or ideas, and not raw materials or machinery. Before we can distribute goods to consumers (first-order goods), we have to have a structure of production of goods ranging from the highest order (analogous to raw materials) to various intermediate orders (analogous to the production of machines for factories that will produce the consumer goods, and the trucks and logistics to get the goods to their final destination), and then the shops on Main Street that will sell the lowest-order goods to consumers.”

According to the Austrian theory to which Hart appeals, consumer goods normally require land, labor, and capital to produce. For each capital good involved in the production of a consumer good, one can in turn inquire: how was it produced? Either land and labor sufficed to produce the capital good, or another capital good was required. In the latter case, we can repeat the inquiry. Eventually, the inquiry will end at a stage with only land and labor as inputs: no capital good is an original factor of production. Production travels forward from original land and labor to consumer goods, but the analysis of the process of production goes in the other direction, from the consumer goods back through the stages of production to the original land and labor. The stages are said to become “higher” as they recede from the consumer goods.

It should be clear that this has little if anything to do with the generation and spread of ideas. The application of the Austrian view to ideas, I take it, is that one begins with “liberal scholarship” This is analogous to the “raw material” at the “highest level”’ that is then passed down the various stages until it reaches the consuming public. The starting point, in sum, is a complex, nuanced, and creative idea that is simplified and made palatable to the public.

Nothing precludes such a process, but it is certainly not necessary. Why must one begin with a creative contribution to scholarship? Perhaps instead, in a particular case, popular ideas came first, and later scholarly work refined them. If you want to build a modern airplane, you cannot do it with bare labor and land on which to stand. You require a vast array of capital goods as well, and these must be produced in the way described by Austrian production theory. To bring an idea to the public, by contrast, you do not need to have as “raw material” a scholarly idea that you will then simplify.

Confusion on this point may stem from the fact that Hayek, a leading contributor to Austrian capital theory, wrote also a famous paper, “The Intellectuals and Socialism,” that deals with the transmission of ideas, In this paper, which Hart discusses, Hayek has a great deal to say about the way in which intellectuals, whom he calls the “secondhand dealers in ideas,” take over the contributions of scholarship and offer them to the reading public. Nowhere, though, does Hayek claim in “The Intellectuals and Socialism” that ideas must be produced in this fashion. Certainly a scholar does not need a “secondhand dealer in ideas” in order to reach a wide audience. Hayek, after all, wrote The Road to Serfdom for the educated public. Neither does he make any connection in his article between what he says about ideas and the Austrian theory of production.

The final topic in Hart’s essay I wish to discuss is his account of Murray Rothbard’s ideas on strategy. Hart says, “For the libertarian movement he advises creation of a Leninist-style ‘cadre’ of committed and knowledgeable individuals who understand both the theory of liberty as well as how it might be implemented in the political world.” Hart goes on to say “Rothbard’s strategic theory might be pursued at greater length in a future post in this discussion, especially his [James] Millian-Leninism and its appropriateness for a movement based upon individual liberty, free markets, and individual responsibility.”

Hart’s remarks convey, unintentionally I am sure, a misleading impression. The unwary reader might surmise that Rothbard was proposing a libertarian version of the Bolshevik party, with its fanaticism and iron discipline. The impression would be enhanced by Hart’s incorrect suggestion that Rothbard’s thought on strategy began in the 1970s, “when he hoped to turn the fledgling Libertarian Party into one modeled on his theory of ‘cadres’ and before he split acrimoniously with [Charles] Koch and the Cato Institute and gave up the idea of shaping the LP in his Millian-Leninist image.”

Rothbard’s began thinking about strategy substantially before the 1970s, and he did not formulate his ideas as a way to influence the Libertarian Party, which did not then exist. When he first spoke of cadres, he did not have in mind a political party, much less a political party in the style of the ruling party in Soviet Russia. In a Memorandum of July 1961, “What Is To be Done?” written for the Volker Fund, Rothbard says: “We are not interested in seizing power and governing the State, and we therefore proclaim, not only adhere to, such values as truth, individual happiness, etc., which the Leninists subordinate to their party’s victory.”[23]

What, though, of that dread word “cadre”? Rothbard intended nothing sinister by it. Rather, he had in mind people who adhered to a consistent set of libertarian principles. Like the Leninists, they were interested in more than day-to-day-“opportunism.” That is to say, they did not find satisfactory as a goal the mere modification of the existing arrangements in way slightly more favorable to the free market. Unlike “‘sectarians,” Rothbard does not insist that one state one’s “full ideological position at all times,” but the hard core, or cadre, “must always aim toward the advancement of libertarian-individualist thought … among the people and to spread its policies in the political arena.”[24]

In a passage from “The Intellectuals and Socialism” that Hart quotes, Hayek makes the same point: “We need intellectual leaders who are willing to work for an ideal, however small may be the prospects of its early realization. They must be men who are willing to stick to principles and to fight for their full realization, however remote.” It is puzzling, for that reason, that Hart entitles the section of his essay that discusses Rothbard, “Hayek vs. Rothbard.”

Endnotes

[20.] John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (New York, 1936), p. 383.

[21.] Leonard Peikoff, The Ominous Parallels ( New York, 1982), p. 24

[22.] Ibid., pp. 24-25.

[23.] David Gordon, ed., Strictly Confidential: The Private Volker Fund Memos of Murray N. Rothbard (Auburn, 2011), p.8. The title of Rothbard’s memo of course echoes Lenin’s famous pamphlet.

[24.] Ibid., p. 9

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.