Liberty Matters

Changing Core Beliefs Takes a Long Time

The comments by George Smith on Lecky and Robertson, and Steve Davies’s interesting reflections on the connections between ideas and social change, have helped me greatly in my thinking about how ideas spread. I want to try to synthesize some of what has been said and then pose a couple of new hypotheses.

The comments by George Smith on Lecky and Robertson, and Steve Davies’s interesting reflections on the connections between ideas and social change, have helped me greatly in my thinking about how ideas spread. I want to try to synthesize some of what has been said and then pose a couple of new hypotheses.It seems to me that George’s fascinating exploration of Stephen, Lecky, and Robertson clarify some of the basic points that David Hart has been sketching. If I understand George correctly, the process of ideational change begins with what we have been calling “first-order thinkers,” in Stephen’s example, people like Bacon, Descartes, and Locke. Their ideas gradually filter into society and influence public opinion, which eventually works to change general attitudes and economic and social policies.

So far so good, but George, drawing on Robertson, makes an important argument at this point. Changes of belief, in matters both “major” and “minor” (corresponding, I think, to David Hart’s distinction between “core” and “noncore” beliefs), come about as a result of reasoning. This is crucial, I think, because it gives us a mechanism, thus far lacking in our discussion, for how ideas are actually spread, namely, through reasoned argument. In this formulation, concepts like Zeitgeist become not the producers of public opinion but their effects. If this description of how ideas are spread is accurate, it is at the same time exciting and daunting. It is exciting because it means that, with the proper sorts of arguments, we can convince people of the truth of our ideas. It is daunting because, as Robertson’s quote hints, most people do not want to put forth the necessary effort to consider and reason through new ideas, especially if these run counter to popular opinion

The other question suggested by this line of reasoning is the length of time it takes for ideas to filter through society, become the subjects of debates and arguments, and eventually change public opinion. David Hart and I have been talking about this offline (I have the advantage of working in the same building as he does), and I’ve come to a couple of tentative hypotheses on the subject.

First, it seems like it takes a very, very long time for abstract “first-order” ideas to make their way into public opinion. Smith and Ricardo, for example, were writing about the importance of free trade and free markets during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but it took until the 1840s for such ideas to become more or less commonplace. Even then, free-trade policies were (and have continued to be) under relentless attack. If we want to take the date of the abolition of the Corn Laws (1846) as an indication of the victory of free-trade ideas, we can say that from the publication of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, it took 70 years for free-trade ideas to see their first significant victory.

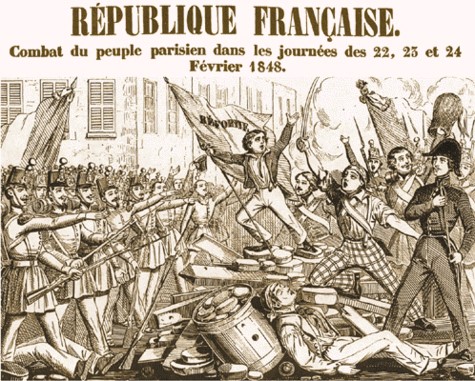

Another interesting example of a change in people’s core beliefs (or major beliefs) involves the abolition of slavery. It is difficult to pin down a seminal text or thinker to mark this movement’s beginning. For centuries in Europe the church and secular authorities had issued various edicts and decrees to regulate or restrict slavery, but the abolitionist movement, as it developed in the 18th and especially the 19th,centuries clearly drew on the natural-rights tradition coming out of the Enlightenment. For convenience, we might take Rousseau’s Social Contract (1762), with its explicit antislavery arguments, as a kind of foundational abolitionist text. In this case the ideas seem to have spread into public opinion somewhat more quickly, at least initially. Some of the new states in the American republic abolished or otherwise restricted slavery shortly after independence from the British Empire. France abolished slavery in 1794 (though it was reintroduced by Napoleon a few years later. It was finally abolished in 1848). Great Britain declared the slave trade illegal in 1807 and abolished slavery throughout the empire in 1833. In the United States slavery was finally outlawed by the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1865, and it was abolished in Brazil in 1888. If we want to use the abolition of slavery in the British Empire as a kind of benchmark for the generalization of antislavery sentiment in European popular opinion, then the span was 72 years

A final example of the spread of ideas traceable from a single philosophical work to a popular belief might be Marxian socialism. While we might with some confidence date the origin of this belief to the publication in 1848 of The Communist Manifesto, picking a date when these ideas became a major influence on public opinion is trickier. The victory of the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 seems like a satisfactory, if problematic, event to mark a victory of the ideas of Marx and Engels, even if the degree to which this victory was based on a change of popular opinion is open to question. Again, we have a span of seven decades.

What this suggests is that it takes a long time for popular opinion, or perhaps more important, people’s core beliefs to be changed by first-order ideas. It is also interesting that 70 years roughly corresponds to an average human lifespan. This might suggest that major beliefs are so deeply held that people in fact almost never change them, and that seismic shifts in popular opinion are necessarily (not just coincidentally) linked to generational changes.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement

“Liberty Matters” is the copyright of Liberty Fund, Inc. This material is put on line to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. These essays and responses may be quoted and otherwise used under “fair use” provisions for educational and academic purposes. To reprint these essays in course booklets requires the prior permission of Liberty Fund, Inc. Please contact oll@libertyfund.org if you have any questions.