William Cobbett, “The Royal Family Of England” (Feb. 1816)

|

The Ruling Class and the State: An Anthology from the OLL Collection[See the Table of Contents of this Anthology as well as the more comprehensive collection The OLL Reader] |

William Cobbett, "The Royal Family Of England" (Feb. 1816)

[Created: January 12, 2018]

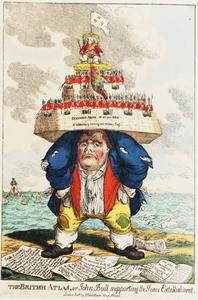

The image is James Gillray, "The British Atlas, or John Bull supporting the Peace Establishment" (1816). [See a higher resolution image and the illustrated essay on "James Gillray on War and Taxes during the War against Napoleon".

Source

William Cobbett, “The Royal Family of England”, Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, Feb. 10, 1816, vol. XXX, no. 6, pp. 161–75. (Written in England Feb. 10.— Published at New-York June 8, 1816.)

Key Words

The Thing; Boroughmungers, a passive tool in the hands of those who own the seats in Parliament, mere puppets in the hands of the Boroughmongers, The Boroughmongers, 23 of whom have from 150 to 200 votes, are our real rulers; the king was a mere instrument; he who grants pensions, or bestows sinecures; some Boroughmonger, in virtue of some bargain for votes, who has really nominated the Bishop; about three or four hundred Boroughmongers actually possess all the legislative power, divide the ecclesiastical, judicial, military, and naval departments amongst their own dependants; It is neither a monarchy, an aristocracy, nor a democracy; it is a band of great nobles, who, by sham elections, and by the means of all sorts of bribery and corruption, have obtained an absolute sway in the country, having under them, for the purposes of show and of execution, a thing they call a king, sharp and unprincipled fellows whom they call Ministers, a mummery which they call a Church, experienced and well-tried and steel-hearted men whom they call Judges, a company of false money makers, whom they call a Bank, numerous bands of brave and needy persons whom they call soldiers and sailors; and a talking, corrupt, and impudent set, whom they call a House of Commons. Such is the government of England; such is the thing.

"The Royal Family Of England" (Feb. 1816)

After the account of the Boroughmungers, which I have given in the last number, the reader will naturally have anticipated, that this is a very inferior set of persons in point of real importance. This is called a “limited monarchy,” and it really is very limited indeed, the person who fills the office of king having no more power of his own than has the bauble put upon his head, or the seat that he sits on. We usually call this branch of authority the Crown, or the Throne, and with great propriety, for the poor creature who wears the one, and sits on the other, is neither more nor less than a passive tool in the hands of those who own the seats in Parliament, and who, in fact, appoint all the Ministers, Ambassadors, Judges, and Commanders, and who, if they were to meet with a refractory king, or one who, from excessive folly, was troublesome to them, would very soon dispose of him, by shutting him up for life, or by some other contrivance, so as never to be pestered by him again.

Of all the objects which the Boroughmongers would most dread, next after free elections, would certainly be a king of sound understanding, good talents, aptness for business, and really desirous to promote the honour and happiness of the country. And, it must be confessed, that, in this view of the matter, they could hardly have been more fortunate than they are in the Guelphs, not one of whom, since their being pitched upon to fill the throne of England, has ever discovered symptoms of a mind much more than sufficient to qualify the possessor for the post of exciseman.

It appears, at first sight, very strange that England should have for its sovereigns a race of foreigners, and that the marriages should be so made up as that no king should, supposing nothing illicit to go on, ever have a single drop of English blood in his veins. But, if we consider these apparent sovereigns, as we ought, nothing more than mere puppets in the hands of the Boroughmongers, we shall find a very substantial reason for this seemingly strange taste. It is the interest of this body of men, to have upon the throne a person for whom the people have no regard. The English nation have a rooted hatred, or, at best, contempt, for all foreigners; yet, be they who or what they may, these foreign princes and princesses always surround themselves with Hanoverians, Brunswickers, and other Germans, and care is taken that the race shall never mix with any English race; so that this contempt, on the part of the people, is constantly kept alive.

The language that is made use of in conversation, with regard to this family, would astonish any stranger. All sorts of names, expressions of contempt, are constantly used by all ranks of people towards them.

The “d___d Germans“ they are called in a lump by the common people; and when the nobility and gentry reject vulgar epithets and terms, it is only to choose others more severe. This abuse is made use of by all parties; by all men in, as well as out of, office. When the War was declared against France, at the rupture of the peace of Amiens, the princes went to the House of Lords to support the address to the Throne. The Duke of Clarence made a speech upon this occasion, and I was standing with a crowd of others below the Bar (as it is called) at the time. The House, which was exceedingly full, were very merry at his expense; and two Peers, who sat close to the bar, at the side of the House on which I stood, indulged themselves in this sort : ” What a Jack-ass!“ said one: ”What a great fool!“ said the other: ”did you ever hear such a beast?“ And, towards the close of the speech, the Royal Duke having declared, that he spoke the sentiments of his whole family, a third Peer exclaimed: ”his family! who the “d—l cares about his family!" All this was said loud enough for twenty or thirty persons to hear, who stood or sat nearest to them. Other Peers were smothering a laugh; some affected to be blowing their noses; and the Lord Chancellor Eldon, sat and looked at the Duke with one of those smiles which contain the double expression of pity and contempt. [163] To be sure the speech was a foolish rant; but, if it came from a Duke of Newcastle or an Earl of Lonsdale, or any other great Boroughmonger, it would have been listened to with the greatest attention and apparent respect.

Strangers to the workings of this system wonder how it comes to pass, that we obey a family, whom we so abuse. The fact is, we do not obey them; and, the very lowest man in the country knows that we do not. The Boroughmongers, 23 of whom have from 150 to 200 votes, are our real rulers; and, it suits them to have the forms of a monarchy, while they possess all the substance of its powers. If the family on the throne were really English, the people would have a regard for them, exclusive of the powerful connexions which an English Royal Family would have in the country, in consequence of marriage alliances. Such a family would be a formidable rival of the Boroughmongers; and might, like the Plantagenets, side with the people against those who have usurped their rights. In such a struggle the people might, perhaps, get some share of the power into their hands. Therefore, the Boroughmongers prefer this race of foreigners; and the lower and more paltry its origin, and the more despicable the character and conduct of the individuals belonging to it, the better it suits their purpose.

I have, since I have been acquainted with the real situation of the Royal family, often laughed at the old story about “ an influence behind the throne greater than ”the throne itself.” This is one of the numerous cheats that have been practised upon the world. What influence could there be of any practical consequence? Charles Jenkinson, who was afterwards Lord Hawkesbury and Earl of Liverpool, and whose, son is Earl of Liverpool now, was looked upon as one of the influencing persons. As if this man, who was once a Page to the king’s father, could have any weight in dictating measures, to which the Boroughmongers had been opposed! as if he and Lord Bute, and three or four other contemptible people, could have supported the king against old Lord Chatham, if the men who had three votes out of every four had not been on the same side’!

The rejection of “Catholic Emancipation” was attributed to the “conscientious scruples“ of the king; and by others to his “obstinacy.” The poor old man had no more to do with it than bad any one of the little land turtles in the American woods. It has always been foreseen, that, if the Catholics are "indulged," as it is impudently called, any further, they will next demand an ”abolition of tithes,“ and the Church demesnes would follow of course. This is property, altogether, worth more annually than a fourth part of all the rent of all the Land and Houses in Ireland. And to whom does this property belong? Why, to the nobility and a few commoners who own the seats in parliament. Three fourths of the Church Livings are their own private property. The rest, and the Bishopricks and other Dignities, they, in fact, cause to be filled with their own relations, or by those who serve them, or whom they choose to have appointed. If, then, we find them in real possession of a quarter part of the rental of the kingdom of Ireland, by the means of the existence of a protestant Church, is it wonderful that they do such abominable acts as they notoriously do, in order to support the Church? Did it need any ”conscientious scruples" on the part of an unfortunate old man, who had no interest in the rejection, to prevent the “emancipation” taking place? Besides, the Emancipation would have opened the place of Judge, Chancellor, Attorney, and Solicitor General, Master of the Rolls, Privy Counsellor, Field and General Officer, Captain and Admiral, and of Parliament men, and Sixty Peers, to Catholics. Was it likely, that those who had, as we have seen in, the last number, all these in their own hands, should call in more persons to share in the rich spoils? Is it usual for men to act thus? Did Cochrane and Cockburn, when they had packed up the plunder of Alexandria, call in the crews at Halifax or Jamaica to partake with them? Ireland is one of the estates of the Boroughmongers; and do men ever call in other men to participate in their rents?

Mr. Fox and his party, who brought forward this measure in 1807, stood pledged, however, to the Catholics. They had given the pledge when they were out of place, and, most likely, when they never expected to get in. But, still, it is surprising that they should have attempted the fulfilment; knowing, as they did, the all-ruling power that was naturally opposed to it. The truth is, they were deceived. Some seat-owners appeared to acquiesce; and the ministers, who were, in the arts of the trade, not half so deep as their opponents, thought that, if they carried their measure, they should have the Catholic Peers and Commoners with them; and should, thus, acquire permanent strength. The Boroughmongers took the alarm. Lords Eldon, and Hawkesbury, (now Liverpool,) and Perceval, were despatched to the king, who was told that he was about to act "in violation of his Coronation Oath,” and that he must turn out the ministers.

The Foxites finding themselves undermined, endeavoured to keep their places by withdrawing the Emancipation Bill from the Table of the House of Commons, on which it was laid, and in which House it had been read a first time. But, it was now too late. The Boroughmongers could not trust them; and out they were driven. That the king was a mere instrument on this occasion is certain; else how came he to approve of the Bill before it was introduced? How came he first to do this, and then, all of a sudden, to turn out his ministers for having proposed the measure? Nay, how came he to put them out, even after they had withdrawn the Bill? If 1 am asked why the Boroughmongers did not vote out the Bill and the Ministers. I answer, that that would have been to expose themselves to great odium, especially in Ireland, every impartial man being for the measure. It was, therefore, much better to throw the failure of it upon the “tender conscience of the king.” And to set up all through England, a tremendous cry of, “God bless the king, and No Popery,” which the new minister did, and with such success, that when Mr. Roscoe offered himself to be re-elected, the people of his own town, where his talents and his virtues were so well known, almost buried him with dirt and stones, amidst shouts of ”Down with the Pope;” and that, too, as the event has proved, while they were paying loads of taxes to restore the Pope and the Inquisition.

But, if those who really knew any thing of the matter could have had any doubt upon this subject in 1807, the events of 1811 and 1812 would have completely removed such doubt; for the king was then shut up; he was put aside; his son [166] was, in fact, put in his place. The king’s conscience, therefore, was no longer an obstacle. The Prince Regent stood pledged to the Catholics both verbally and in writing. Yet he did not attempt to redeem the pledge. Suppose him, if you like, a faithless man; but faithless men do not, any more than others, voluntarily and gratuitously expose themselves to the hatred and contempt of mankind. At first, he had only limited powers. The Boroughmongers actually openly kept a part of the very exterior of royalty in their own hands, lest a man, on whom they could not depend, should be guilty of some thing that would rouse the people against him. But, at the end of a certain time, they enlarged his powers. To this time his old friends and companions looked with eagerness. The Catholics thought, to be sure, that they should now get there long-sought emancipation.

All London heard the execrations that were, upon this occasion, poured out upon the Prince. He was called every thing descriptive of baseness and perfidy; when be really had no more power with respect to Catholic Emancipation than I had. He might be perfectly sincere, when he pledged himself to the Catholics; nor is there any good reason to suppose that he was not sincere. As Duke of Cornwall he owns two seats in that County. His two Members voted for the Emancipation. Even Castlereagh, to make good his pledge, was suffered to vote for it, in 1812. But, when there appeared so large a majority against it, was it not then become clear, that the conscience of the king had been a mere pretext? Could any man, however stupid, still be deluded by so stale a trick? What miserable nonsense is it, then, to talk of “an influence behind the throne greater than the throne itself!” Will any body believe, that any favourites of the Prince could have persuaded him thus to falsify his word? Why should they? His favourites had been Lord Holland, Mr. Tierney, Mr. Sheridan, and, generally, the friends of Catholic Emancipation. He had supposed that some real power would come into his hands, when he should be king; but, he soon found his mistake; he found himself to be a mere tool in the hands of the owners of the seats in parliament; namely, about 120 Boroughmongers, who. have, at all times, a dead majority; and though they very willingly would permit the Prince to do such odious things as the creating of Bate Dudley a Baronet, and are glad to see him disgrace himself and disgust the people by his amours, his excesses, and his squanderings, take special care that he shall do nothing that shall trench upon their real and solid dominion.

Of the real nothingness of the king and the people called his ministers there were ample proofs in the history of Pitt. It is very well known, that Pitt, who had formed to himself a hope of immortal fame from his financial schemes, went with extreme reluctance into the war with France in 1793. The account of the conversation between him and Mr. Maret, which was published in the Annual Register, from a translation of Mr. Maret’s notes, proves, that the minister, who was thought to rule in England, was in great fear, lest the French Convention should, by their violence, give a handle to the Aristocracy here to force him into the war. His chief reliance was upon the Opposition, which was then formidable. He hoped that the great seat-owners, who belonged to that Body, and who had so long affected to follow Mr. Fox, would continue firmly united against his ministry; in which case, he could have resisted the warlike commands of his own masters, that is to say, the Boroughmongers on his side. But, his hopes were disappointed. It has been a thousand times stated, that the Court Influence drove him into the war. That the king told him "war, or turn out.’ This was, indeed, the alternative; but, the source of the command was different; and, upon this occasion, it was openly seen to be so.

A great body of Boroughmongers, who had, until now, been in the opposition, finding that the example of France might produce reform in England, the necessity of which reform, by the by, was most ably urged by men of great talent and weight, resolved to have for minister some man that should go to war with France. They found that Mr. Fox would not; and, after due preparations, over they came to Pitt, who would rather have had the company of Satan himself. Amongst the leaders of the seceders from Mr. Fox were the Duke of Portland, Lord Fitzwilliam, and Lord Spencer, each of whom having ten times the influence of Pitt himself. Burke, who had been the trumpeter of the war, and who had been for two years labouring to work people’s minds up to it, was a mere tool in the hands of Earl Fitzwilliam, in one of whose seats he sat. He belied his conscience through the whole of his work; but, he received, not only his seat, but his very bread, at the hands of this opulent nobleman, who was bent upon preserving his borough powers and his titles, or, at least, to take the chances of war for that preservation. Earl Spencer was, at the time of his leaving Mr. Fox, asked by a gentleman, who had long voted with that party, and who was opposed to the war, what were the motives that could have induced a man so worthy as his Lordship to join in such an enterprize. “I will be ”very frank with you,“ said Lord Spencer, “and save you the trouble of discovering my motives. My lot is cast amongst the nobility. It is not my fault that I was thus born, and that I thus inherit. I wish to remain what I am, and to hand my father’s titles and estates down to my heirs. I do not know that I thus seek my own gratification at the expense of my country, which has been very great, free, and happy, under this order of things. I am satisfied, that if we do not go to war with the French this order of things will be destroyed. We may fall by the war; but we must fall without it. The thing is worth fighting for, and to fight for it we are resolved.” The substance of this has been stated in print by Mr. Miles, in his letter to the Prince of Wales; but, I have here put down the words as I heard them from the gentleman who had the conversation with Lord Spencer, having made, in 1812, a memorandum of them in a few minutes after I had heard them.

When one guts thus behind the curtain, how amusing it is to hear the world disputing and wrangling about the motives, and principles, and opinions of Burke! He had no notions, no principles, no opinions of his own when he wrote his famous work, which tended so much to kindle the flames of that bloody war, which, in its ramifications, have reached even to the Canadian Lakes and the Mexican Gulf. He was a poor, needy dependant of a Boroughmonger, to serve whom, and please whom, he wrote ; and for no other purpose whatever. His defence of “our own Glorious Revolution,” under the " deliverer William," and his high eulogium of that king for introducing and ennobling a Dutch family or two, seem to be quite unaccountable to most readers, as they are disgusting to all; but, no longer wonder then, when we reflect, that Earl Fitzwilliam is the descendant of a natural son of William the Third; and that the ancestors of Bentick, Duke of Portland, were Dutchmen, who came to England, and were here ennobled, in the same king’s reign. And yet, how many people read this man’s writings as if they had flowed from his own mind; and who seem to regard even the pension, which Lord Fitzwilliam soon after the change procured for him and for his widow after him, as no more than the proper and natural reward for his great and disinterested literary exertions in the cause of ”social order!”

From this account of the real cause of the war of 1793, it is clear how the world, in general, have been deceived as to the king’s commands upon that occasion He, I dare say, wished for war. It was the cause of kings and electors as well as of Boroughmongers. But, his mere wishes were unsupported by any power of his own. And, as to Pitt, if he had taken his place with Fox on the Opposition benches, he would have found, as he afterwards did, when he opposed his own understrapper, Addington, that out of his majority of four hundred and thirty votes, not more than thirty votes would have gone over with him.

In 1801 Pitt resigned, because Catholic Emancipation was not permitted to be brought forward. But, when the Boroughmongers, in 1804, found, upon the renewal of the war, that Addington was insufficient for the purpose, they recalled Pitt, who, however, in spite of all his pledges, never dared to talk of Catholic Emancipation again, to the day of his death. Upon the occasion of this last change, it is notorious, that the king discovered his reluctance in all possible ways; and when it actually took place, it drove him into one of his fits of insanity. He personally liked Addington, who is a smooth supple creature, though very artful, and can be, when he chooses, very malignant. His father was a mad-doctor, had treated the king with great tenderness, while others used harsh, not to say cruel, remedies. Addington, who bad always been an underling, behaved in that humble manner which the king and queen and royal family liked very much; and, besides, he did all their little jobs in the way of pensions and places for their personal friends. So that the life they led with him was perfect elysium, compared with what they were obliged to endure from the neglect and insolence of Pitt, who was domineering towards every living creature, the Boroughmongers excepted. But, the war was again begun. Addington was thought by the seat-owners unlit for their purpose; both sides of the House joined to put him out; and, a very little after he had left Pitt in a minority of thirty-seven, Pitt saw him (the Members being all the same persons) in a minority of about the same number! Where was now that “influence behind the throne greater than the throne itself?" What was become of it upon this memorable occasion? The truth was, that Pitt was thought, by those who had the real power in their hands, the fittest man to carry on the complicated machine ; and, no sooner had they made up their minds, than they put out the poor thing who had filled his place for a couple of years, keeping in almost all the rest of the ministry.

Is it possible for any thing to show, more clearly than these facts do, the nothingness of the Royal Family and the Ministers, if considered in any other light than that of puppets and tools? When the present cabinet was formed, the Earl of Lonsdale, who owns nine seats, had made it a point that Lord Mulgrave should be Master General of the Ordnance. It being found difficult to comply with this request without clashing in another quarter, the Earl of Lonsdale was informed, that His Royal Highness the Prince Regent had been pleased to make an arrangement by which Lord Mulgrave would have a very lucrative post out of the cabinet, sensible men, most likely, not wishing to have such an empty coxcomical gabbler in the cabinet. Upon seeing this information by letter, at one of his country seats, it is said that Lord Lonsdale exclaimed: “His Royal Highness has been pleased, has he! Bring me my boots!” Whether this be true or not, it is very certain that he undid the arrangement, and that he put Lord Mulgrave into the Ordnance and the Cabinet. In fact, it is notorious, that the Prince has no power at all of any public consequence; that he cannot procure the appointment to any office of considerable trust or emolument; that it is not he that chooses Ministers, Ambassadors, Judges, Commanders, or Governors; that it is not he who grants pensions, or bestows sinecures; that it is not he who gives to the Dean and Chapters leave to elect Bishops any more than it is the “ Holy Ghost” that inspires the said Deans and Chapters upon the occasions when these at once impious and farcical scenes are exhibited. Of all the elections, that ever the world heard of, these are the most curious.

When a Bishop dies, another must be put in his place. The Bishop is elected by the Dean and Prebends of the Cathedral Church of the Diocess. The king, who is called the head of the Church, sends these gentlemen, who are called the Dean and Chapter a congé de lire, or a leave to elect; but he sends them, at the same time, the name of the man, whom, and whom only, they are to elect. With this name in their possession, away they go into the Cathedral, chant psalms and anthems, and then, in a set form of words, invoke the Holy Ghost to assist them in their choice. After these invocations, they, by a series of good luck wholly without a parallel, always find that the dictates of the Holy Ghost agree with the recommendation of the king. And, now, if any man can, in the annals of the whole world, find me a match for this mockery, let him produce it. But even this shockingly impious farce loses part of its qualities, unless we bear in mind, that it is not the king, but some Boroughmonger, in virtue of some bargain for votes, who has really nominated the Bishop; and, that the King, the Minister, the Dean and Chapter, and the Holy Ghost proceeding, all neither more nor less than so many tools in the hands of the said Boroughmonger. Good and pious people wondered amazingly that the Holy Ghost, or even the king, should have pitched upon the present gentleman to fill the Archbishop’s Chair of Canterbury; but, these good and pious Church people did not know, that the Duke of Rutland had, as he still has, seven or eight votes of his own in the two Houses, besides, perhaps, twenty more that he could, upon a hard pinch, make shift to borrow.

It makes me, and hundreds besides me, laugh to read, in American and French publications, remarks on the men engaged in carrying on this curious government of ours. We laugh at the idea of the influence of the Crown; of the party of Pitt; of the party of Fox; of the intrigues of this Minister, of the powerful eloquence of that Minister; of those great men, the Wellesleys, and Liverpools, and Castlereaghs, and Cannings, on the one side; and the Tierneys, and Homers, and Broughams, and God knows who, on the other side; and the Thorntons, and Wilberforces, and Banks’s, and Romilys, and the rest of that canting crew in the middle. We know them all ; yea, one and all, to be the mere tools of the Boroughmongers; and, that, as to the deciding of any question, affecting the honour, liberty, or happiness of the country, the Duke of Newcastle, who was, only a few years ago, a baby in his cradle, had, even while he was living upon pap, more power than this whole rabble of great senators all put together; and, I dare say, now that he is grown up to be a young man, he pays, much more attention to the voice of his fox-hounds than to the harangues of these bawlers, and that he has more respect for the persons and motives of the former than for those of the latter. One thing I can state as a certainty; and that is, that, if I were in his place, I should flee to the dog-kennel as a relief from that filthy den, the House of Commons.

"The king’s friends” is an expression frequently used. Poor man! He has no friends, unless it be in his own family, and amongst his and their menial servants, the greater part of whom are Hanoverians and Brunswickers. The common people do not hate the Royal Family; they despise them too much to hate them. They listen greedily to all the dirty stories about the Queen and her Daughters, of which I have, for my part, never heard any thing bordering upon the nature of proof. Every body speaks ill of all the sons; they blackguard them in all manner of ways. In print, indeed, the Attorney General takes care that a little decorum should be observed; but, even he suffers the assailants to go pretty good lengths. The story at this moment (10th Feb.) is, that the Prince Regent is mad. In vain is there no proof of this; in vain do the physicians report, that his ailment is merely the gout. People will not believe this. They laugh at you if you affect to believe it. The life that the Prince has led may be easily guessed at from the following fact, for the truth of which I refer to publications in London notorious to every body. One Walter, now dead, the proprietor of a newspaper called the Times, which is now carried on by his son, published, during the first agitation of the Regency question, previous to the French war, some outrageously gross libels, very false as well as foul, against the Duke of York and the Prince of Wales. Walter, who was a very base and infamous fellow, was prosecuted by the Attorney General, sentenced to be imprisoned two years for each libel, and to pay a fine for each. The Treasury itself (Pitt at the head of it) were the authors of the libels. Walter threatened to give up the authors. The, Treasury gave him a sum of money to keep silence; and, after he had suffered the two years imprisonment for the libel on the Duke, the Prince obtained the scoundrel’s pardon for the libel on himself, which Walter repaid by every species of malevolence towards the Prince to the day of his death, the Prince’s enemies being better able to pay the ruffian than he was!

Now, let any one suppose what the situation of this family must be, when the Treasury itself could unite, and cause to be published, infamous libels against two of the King’s sons! And, the truth is, that the whole family, the Prince Regent not excepted, are compelled to subsidize the newspapers, in order to blunt or repel, the shafts aimed, or launched forth, against them. If any one could paint this part of our press in its true colours, it would shock every man of common justice. The fears of the whole family are constantly kept alive. They know very well what is said about them. However false the story, they dare not attempt to contradict it; for the bare attempt alone would be produced as proof of their guilt. The sons and daughters cannot marry without leave of the Boroughmongers, as was recently shown in the case pf the Duke of Cumberland. He did, indeed, marry, and by his brother’s consent, which was precisely what the law required; but, because the Prince had not asked their leave, they would not give him a farthing of money, though such grants have always been customary in like cases. And, what is more, they prevented the Queen from receiving his wife at court. It is true, that very bad whispers had been long afloat about the Duke, and I do not say, because I do not know, that they were without foundation; but, I believe, his great sin, a sin for which most certainly there is no forgiveness for him in this world, was his very foolish attempt to uphold Addington against the Boroughmongers, and which attempt, nevertheless, did not succeed for one single day. With what truth the story is told of the poor old king’s expressing his resolution, upon one occasion, to go off to Hanover, I do not know; but really one can easily believe, that a man would go almost any where, and live almost any how, or with almost any body, to get out of such a state of mock-majesty and of real slavery.

The “Royal Dukes,” as they are called, in order to gain a little popular favour, run about to Bible Societies, Lancaster schools, sometimes to societies for assisting lying-in women, and to the most popular Methodist Meeting Houses, when any Thundering Preacher holds forth on a popular occasion. Their names are in all great subscription Lists; and they make speeches on many of these occasions; and always give away some of their money. All this only exposes them to ridicule. The Boroughmongers never expose themselves in this way. They are at their great country seats with their packs of hounds and troops of hunters, and with their good cheer for their numerous guests. Not a single country seat has the Royal Family; not an acre of land; not a pack of hounds, except the Stag-hounds kept up for the use of the old king! The kings of England had, formerly, immense landed estates. They lived upon these estates. They wanted no public money, except for purposes of war, and sometimes they carried on war out of their own purses.

The Boroughmongers took all these estates away from the Guelphs, in the early part of this king’s reign; they have divided the greater part of them amongst themselves, and settled a pension, or, what they call a Civil List, on the king in lieu of them, thus exposing him and his family to all the odium that the annual exhibition of a great charge upon the public naturally excites and keeps alive.

After this view of the situation of this family how we must laugh at De Lolmes’ pretty account of the English Constitution. After seeing that about three or four hundred Boroughmongers actually possess all the legislative power, divide the ecclesiastical, judicial, military, and naval departments amongst their own dependants, what a fine picture we find of that wise system of checks and balances, of which so much has been said by so many great writers! What name to give such a government it is difficult to say. It is like nothing that ever was heard of before. It is neither a monarchy, an aristocracy, nor a democracy; it is a band of great nobles, who, by sham elections, and by the means of all sorts of bribery and corruption, have obtained an absolute sway in the country, having under them, for the purposes of show and of execution, a thing they call a king, sharp and unprincipled fellows whom they call Ministers, a mummery which they call a Church, experienced and well-tried and steel-hearted men whom they call Judges, a company of false money makers, whom they call a Bank, numerous bands of brave and needy persons whom they call soldiers and sailors; and a talking, corrupt, and impudent set, whom they call a House of Commons. Such is the government of England; such is the thing, which has been able to bribe one half of Europe to oppress the other half; such is the famous "Bulwark of religion and social order,” which is now about, as will be soon seen to surround itself with a permanent standing army of, at least, a hundred thousand men, and very wisely, for, without such an army, the Bulwark would not exist a month.