Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics Vol. 5 (1648) (2nd ed)

Tracts on Liberty by the Levellers and their Critics, Volume 5 (1648) (2nd. revised and enlarged Edition)

[Note: This is a work in progress]

Revised: 25 May, 2018.

Publishing history of vol. 5 (1648):

- 25 May, 2018: added 14 new titles from LT9, 3 from LT10, “Petition of 18 Jan. 1648”

- 12 Aug 2017: 1st ed. of vol. 5 put on the OLL website. Contains 30 texts. </titles/2600>

Note: As corrections are made to the files, they will be made here first (the “Pages” section of the OLL </pages/leveller-tracts-summary>) and then when completed the entire volume will be added to the main OLL collection (the “Titles” section of the OLL) </titles/2595>.

- Tracts which have not yet been corrected are indicated [UNCORRECTED] and the illegible words are marked as &illegible;. Some tracts have hundreds of illegible words and characters.

- As they are corrected against the facsimile version we indicate it with the date [CORRECTED - 03.03.16]. Where the text cannot be deciphered it is marked [Editor: illegible word].

- When a tract is composed of separate parts we indicate this where possible in the Table of Contents.

For more information see:

- Summary of the Leveller Tracts Project </pages/leveller-tracts-summary>

- The Complete Table of Contents </pages/leveller-tracts-table-of-contents>

Table of Contents

-

Introductory Matter (to be added later)

- Introduction to the Series

- Publishing and Biographical Information

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

-

Editorial Matter (to be added later)

- Editor’s Introduction

- Chronology of Key Events

- Tracts in Volume 5 (1648)

- [CORRECTED - 24.08.16] T.126 (5.1) William Prynne, A New Magna Charta (1 January, 1648).

- [CORRECTED - 24.08.16] T.127 (9.20) Thomas Jordan, The Anarchie or the blessed Reformation since 1640 (11 January, 1648).

- [[CORRECTED - 24.08.16 - 30 illegibles] T.128 (5.2) William Prynne, The Petition of Right of the Free-holders and Free-men (8 January, 1648).

- [CORRECTED - 24.08.16 - 4 illegibles] T.129 (5.3) William Prynne, The Machivilian Cromwellist and Hypocritical perfidious New Statist (10 January, 1648).

- PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED T.302 [1648.01.18] (5.7) Anon., The Petition of 18 January 1648 (18 January, 1648).

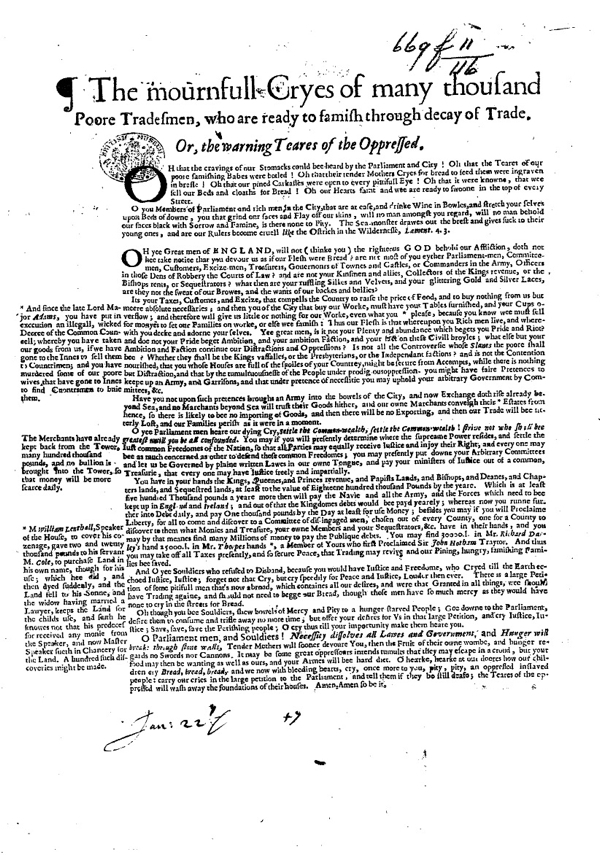

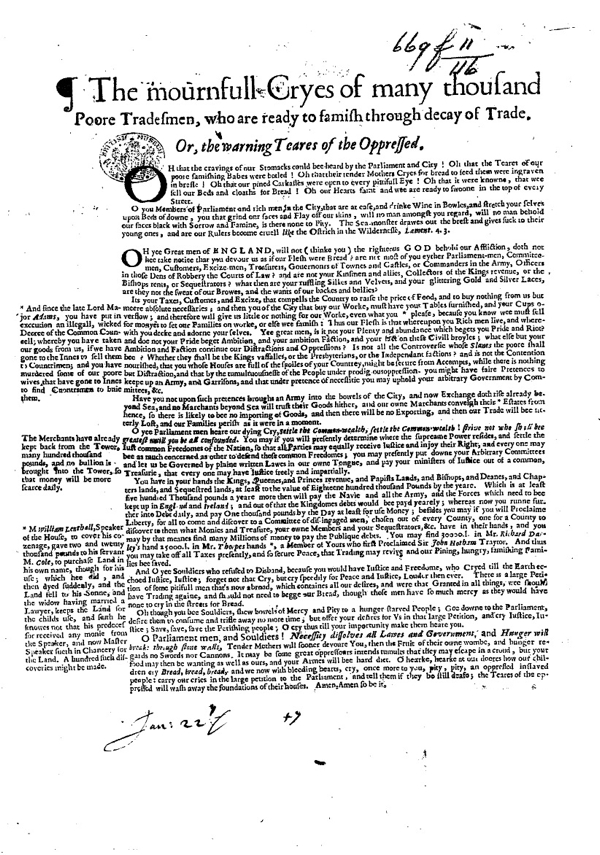

- [CORRECTED - 06.07.16 - 2 illegibles] T.130 (9.21) Anon., The Mournfull Cryes of many thousand Poore Tradesmen (22 January, 1848).

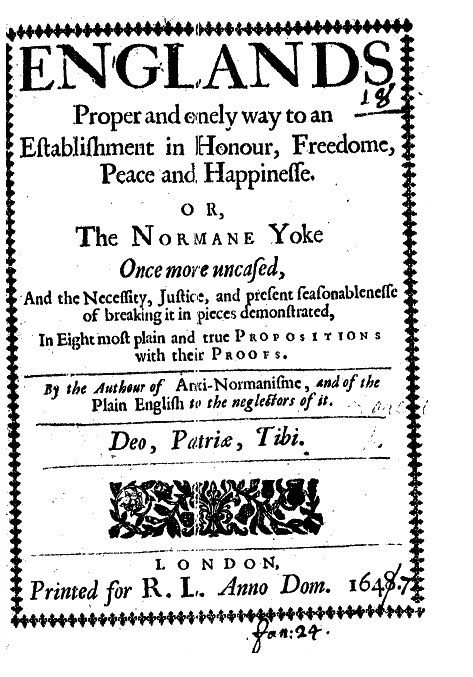

- [CORRECTED - 25.08.16 - 3 illegibles] T.131 (9.22) John Hare, Englands Proper and onely Way to an Establishment in Honour, Freedome, Peace and Happinesse (24 January, 1648).

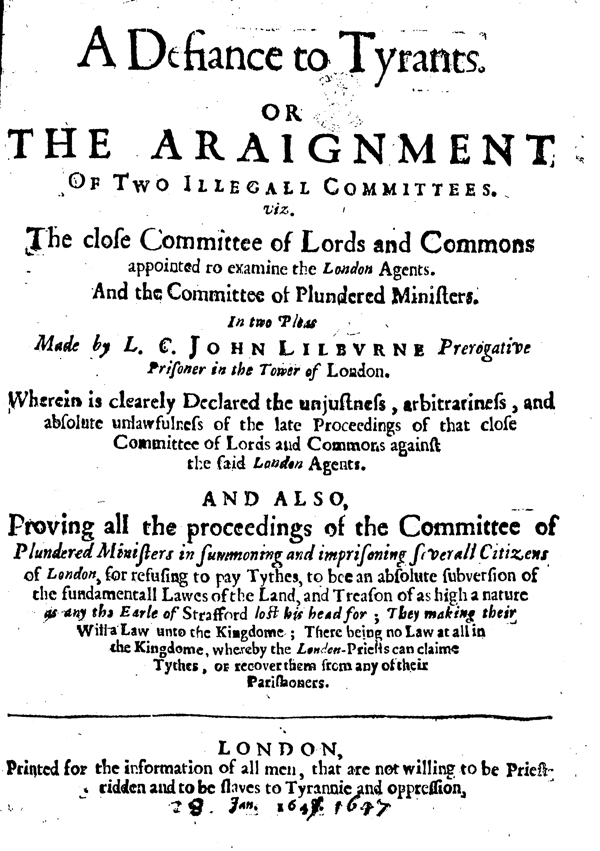

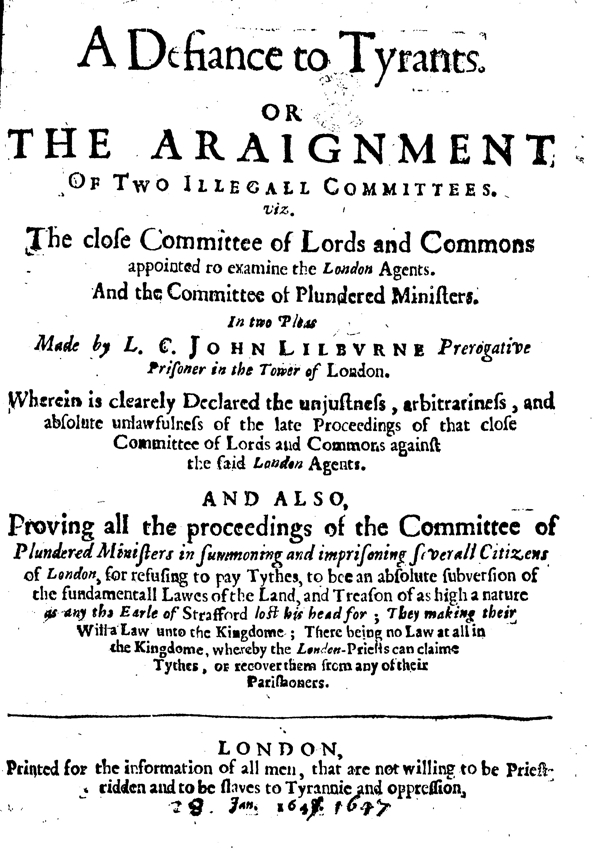

- [CORRECTED - 25.08.16- 23 illegibles] T.132 (5.4) John Lilburne, A Defiance to Tyrants (28 January, 1648).

- A PLEA Made by L. Col. John Lilbvrne, Prerogative Prisoner in the Tower of London, the second of Decem. 1647. Against the proceedings of the close and illegall Committee, of Lords and Commons

- Postscript

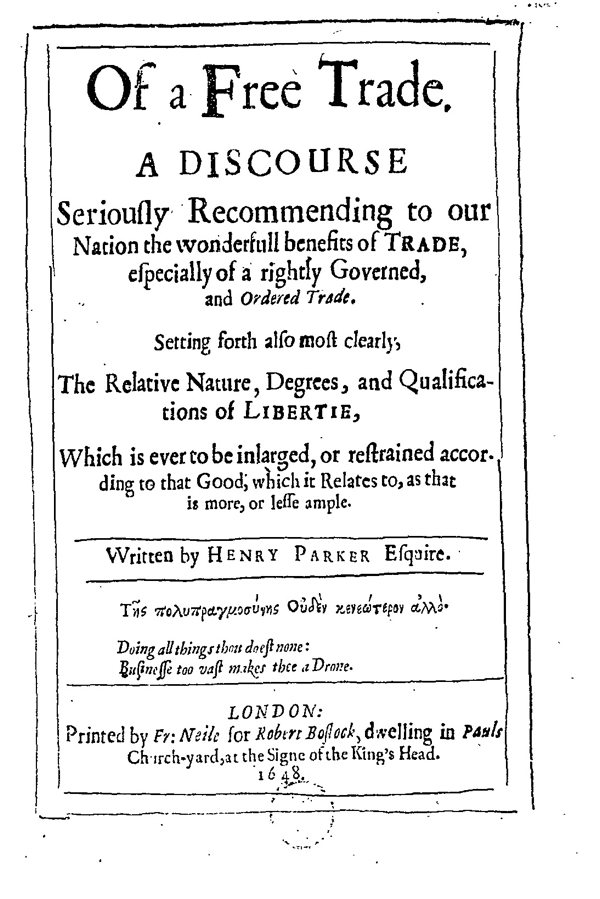

- [CORRECTED - 23.06.16 - 3 illegibles] T.133 (5.5) Henry Parker, Of a Free Trade (5 February, 1648).

- TO THE RIGHT WORSHIPFULL JOHN KENRICK Alderman of London, Governour of the Merchant Adventurers of England. TO THE RIGHT WORSHIPFULL ISAAC LEE, Deputy of the said Company of Merchant Adventurers residing at Hamburgh

- A DISCOURSE CONCERNING Freedom of Trade.

- An Ordinance of the Lords and Commons in Parliament Assembled. For the upholding of the Government of the Fellowship of Merchant Adventurers of England

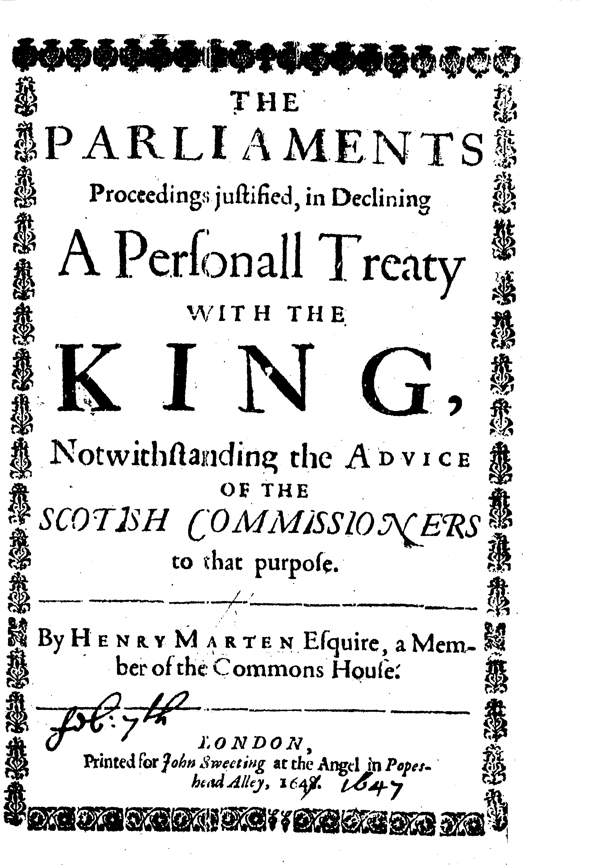

- [CORRECTED - 27.09.16 - 4 illegibles] T.134 (5.6) Henry Marten, The Parliaments Proceedings justified (7 February, 1648).

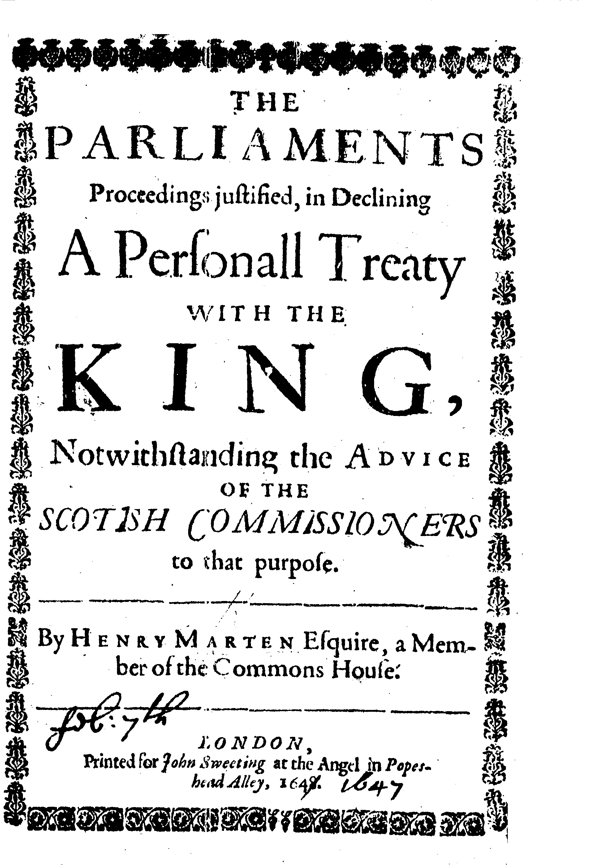

- [CORRECTED - 27.09.16 - 56 illegibles] T.135 (9.23) William Prynne, A Publike Declaration and Solemne Protestation of the Freemen of England and Wales (7 February, 1648).

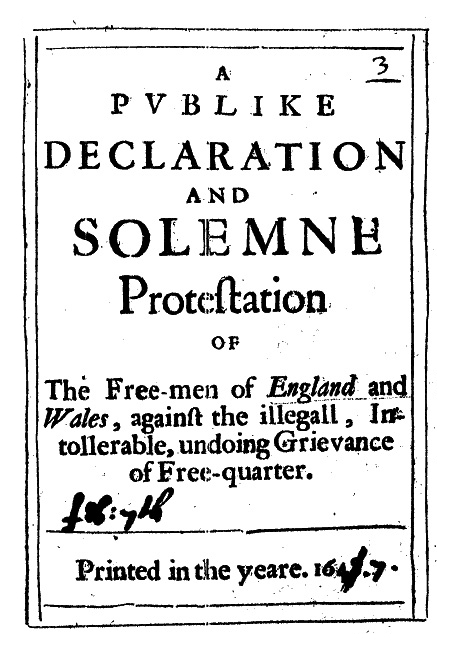

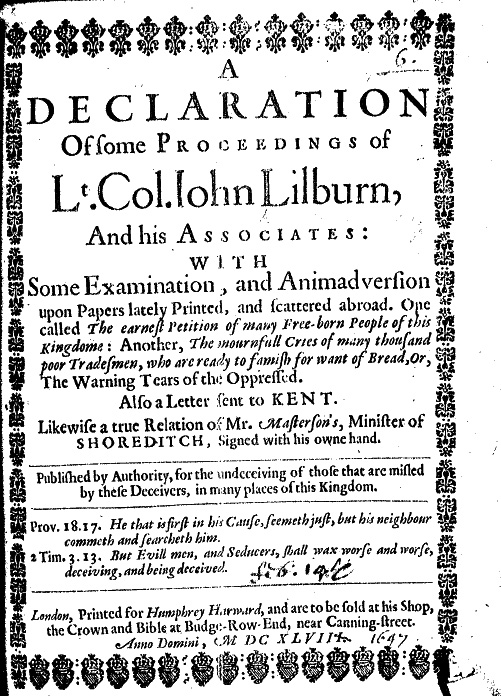

- [CORRECTED - 6.07.17 - 40 illegibles] T.136 (5.7) [John Lilburne], A Declaration of some Proceedings of Lt. Col. John Lilburn (14 February, 1648).

- A Declaration of some Proceedings

- At a meeting in Well-Yard, in, or neer Wapping, at the house of one Williams a Gardiner, on Monday the 17 of Ianuary. 1647.

- To the Supream Authority of England, the Commons Assembled in Parliament. The earnest Petition of many Free-born People of this Nation ("THAT the devouring fire of the Lords wrath")

- The mournfnll Cryes of many thousand poor Tradesmen, who are ready to famish through decay of Trade. Or, The warning Tears of the Oppressed.

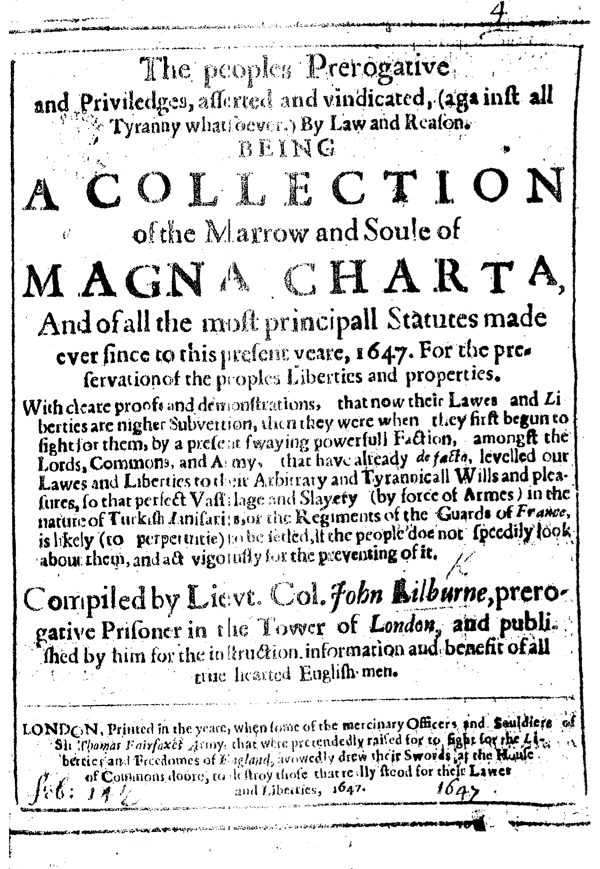

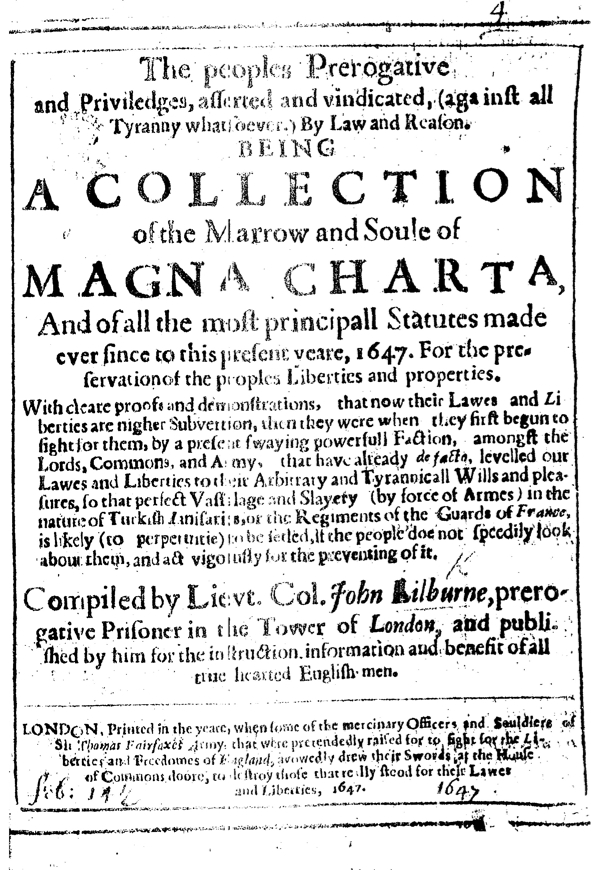

- [CORRECTED - 10.08.17 - 295 illegibles] T.137 (5.8) John Lilburne, The Peoples Prerogative and Priviledges (17 February, 1648).

- To all the peaceable and well minded people of the Counties of Hartfordshire and Buckinghamshire,

- A proeme, to the following collection and discourse

- The Bill of Atainder that passed against Thomas Earle of STRAFFORD.

- Other Documents

- A Defence for the honest Nown substantive Soldiers of the Army, against the proceedings of the Gen. Officers to punish them by Martiall Law.

- Plea of William Thompson, Englands Freedome, Souldiers Rights (14 Dec., 1647)

- Letter To his Excellency Sir Thomas Fairfax Knight, Captaine. Generall of the Forces in the Nation for Importiall Justice and Libertie

- Petition To the right Honourable his Excellency Sir Thomas Fairfax Knight, Captain Generall of all the forces raised in the Kingdome of England.

- The humble Petition of some of your Excellencies Officers and Soldiers being under the custodie of the Marshall Generall

- Postscript

- To the Right Honourable the Lords and Commons assembled in both Houses of Parliament. The Humble Petition of Henry Moore Merchant.

- A new complaint of an old grievance, made by Lievt. Col. Iohn Lilburne, Prerogative prisoner in the Tower of London. Novemb. 23, 1647. To every Individuall Member of the Honourable House of Commons

- A Defiance to Tyrants. Or a Plea made by Lievt. Col. Iohn Lilburne Prerogative Prisoner in the Tower of London, the 2. of Decemb. 1647.

- Postscript

- The Proposition of Lievt. Col. John Lilburne, prerogative prisoner in the Tower of London, made unto the Lords and Commons assembled at Westminster, and to the whole Kingdome of England (2 Oct. 1647)

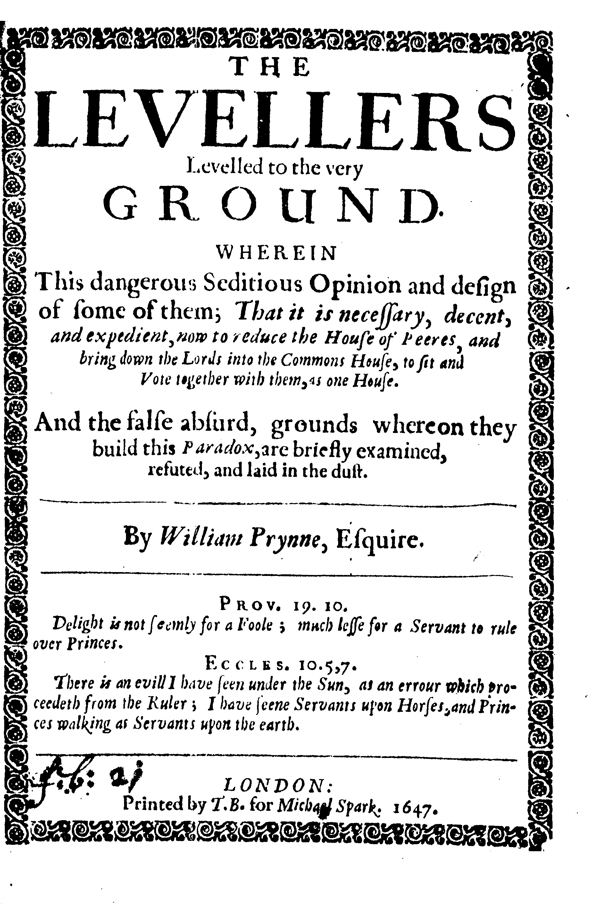

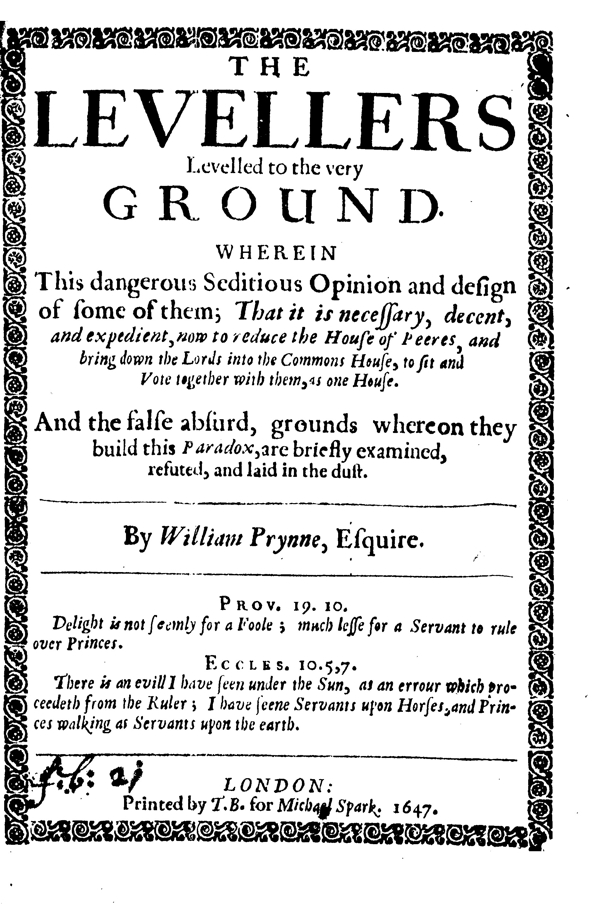

- [CORRECTED - 17.07.17 10 illegibles] T.138 (5.9) William Prynne, The Levellers Levelled to the very Ground (21 February, 1648).

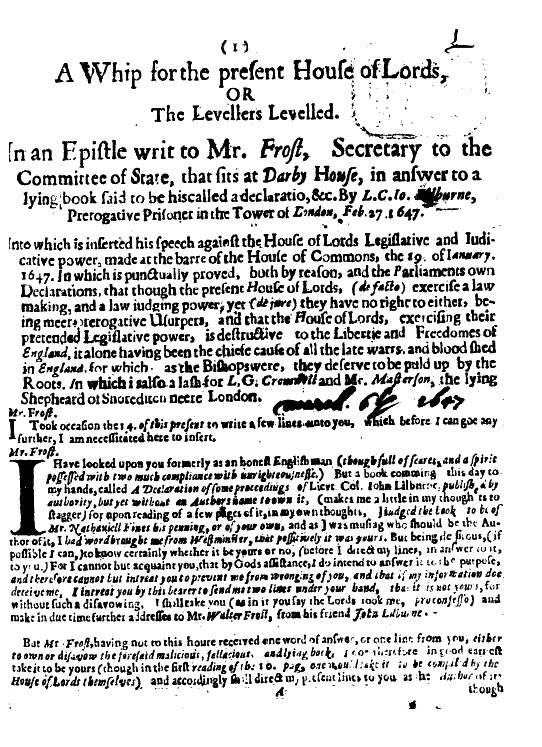

- [UNCORRECTED - 557 illegibles] T.139 (9.24) John Lilburne, A Whip for the present House of Lords (27 February, 1648).

- A Whip for the present House of Lords

- The Proposition of Liev. Col. Iohn Lilburne made unto the Lords and Commons assembled at Westminster, and to the whole Kingdome of England (2 Oct. 1647)

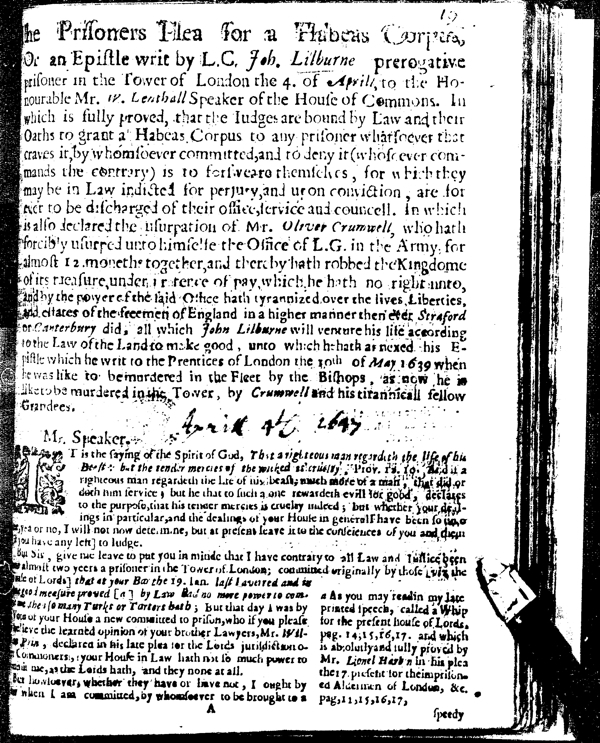

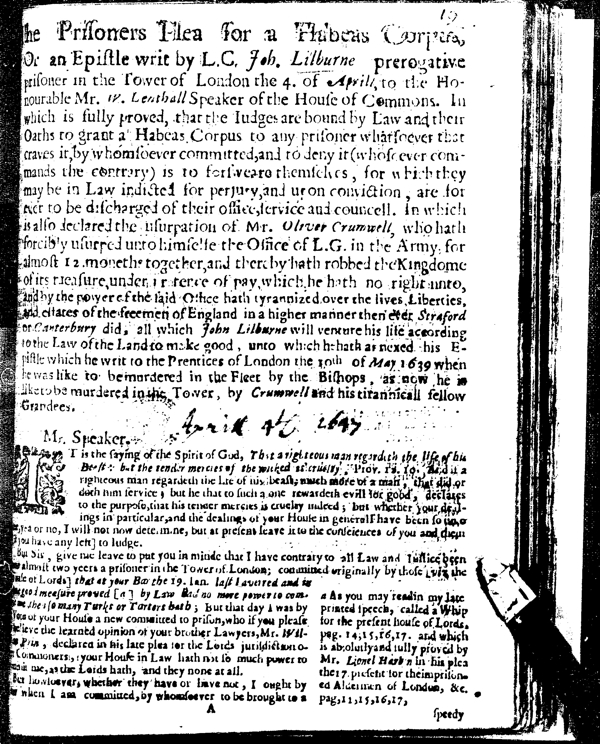

- [CORRECTED - 12.08.17 533 illegibles] T.140 (5.10) John Lilburne, The Prisoners Plea for a Habeas Corpus (4 April, 1648).

- The Prisoners Plea for a Habeas Corpus

- To the Honourable the Iudges of the Kings Bench. The Humble Petition of Levt. Col. Iohn Lilburne Prisoner

- Letter To all the brave, couragious, and valiant Apprentizes of the honourable City of London, but especially those that appertain to the worshipfull Company of Clothworkers

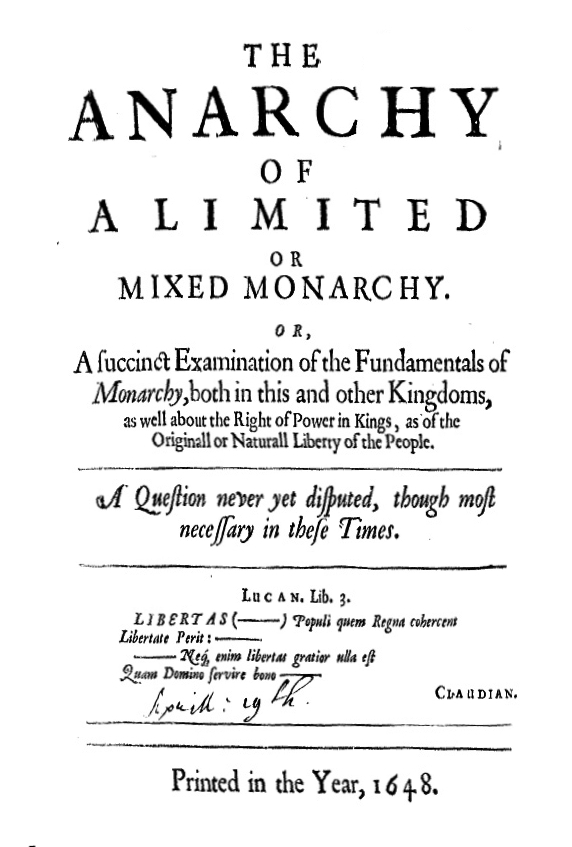

- [CORRECTED - 17.07.17 - 8 illegibles] T.141 (5.11) Sir Robert Filmer, The Anarchy of a Limited or Mixed Monarchy (10 April, 1648).

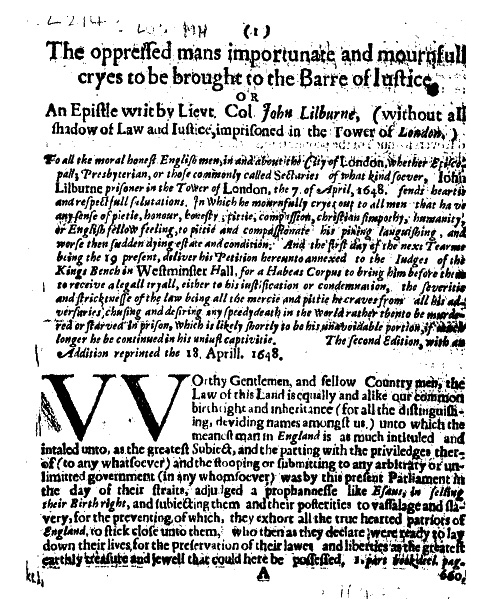

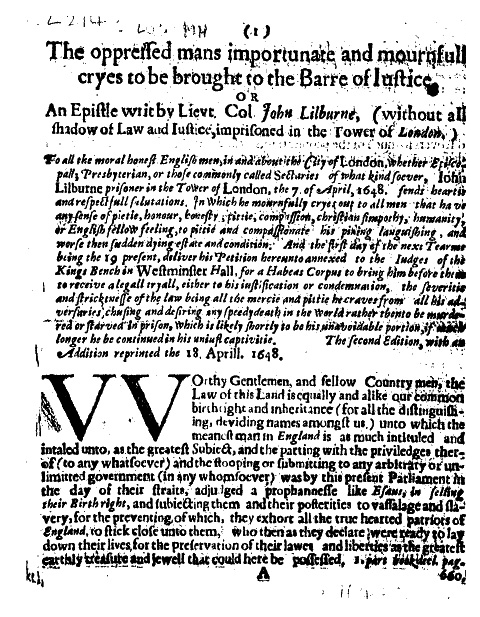

- [CORRECTED - 18.07.17 - 20 illegibles] T.125 (10.12) John Lilburne, The Oppressed Mans importunate and mournfull Cryes to be brought to the Barre of Justice (1648).

- Epistle (7 April, 1648)

- Petition (18 April, 1648)

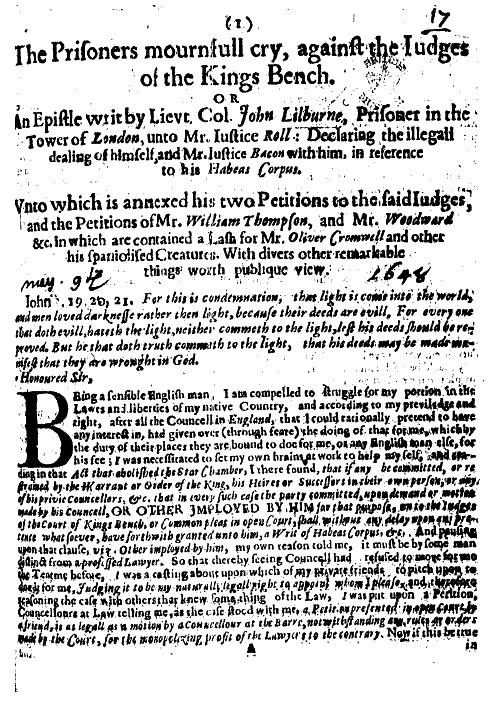

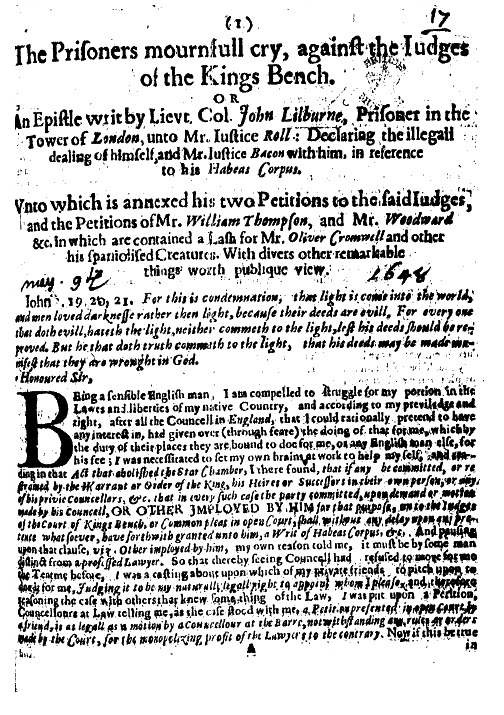

- [UNCORRECTED - 103 illegibles] T.142 (10.13) John Lilburne, The Prisoners mournfull Cry, against the Judges of the Kings Bench (9 May, 1648).

- Epistle unto Justice Hall (1 May, 1648)

- Petition 19 April, 1648

- Petition 25 April, 1648

- Petitions of Mr. Woodwood and Mary Collins

- Instructions to his Soliciter concerning his Habeas Corpus (19 April, 1648)

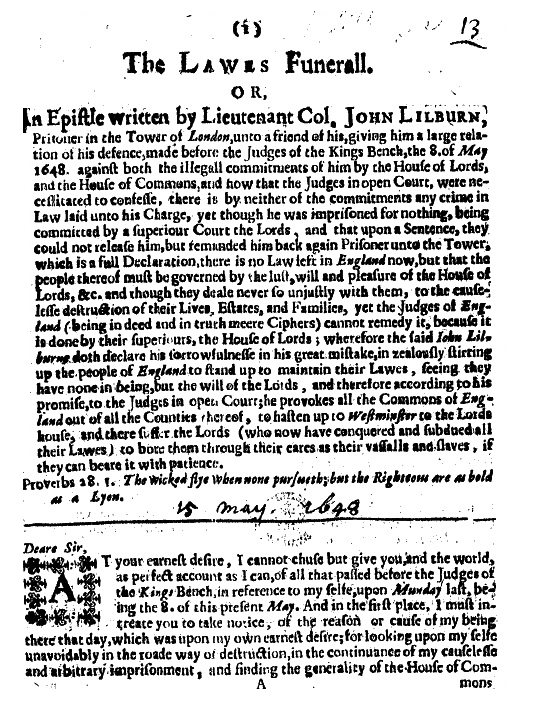

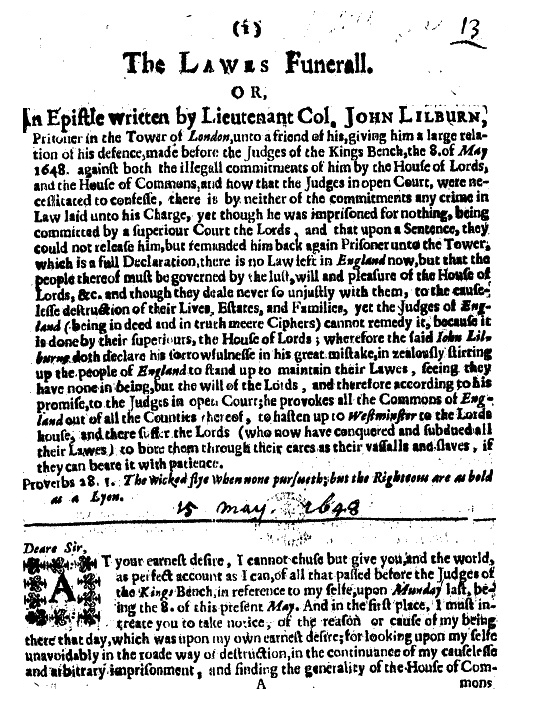

- [UNCORRECTED - 149 illegibles] T.143 (10.14) John Lilburne, The Laws Funerall (15 May, 1648).

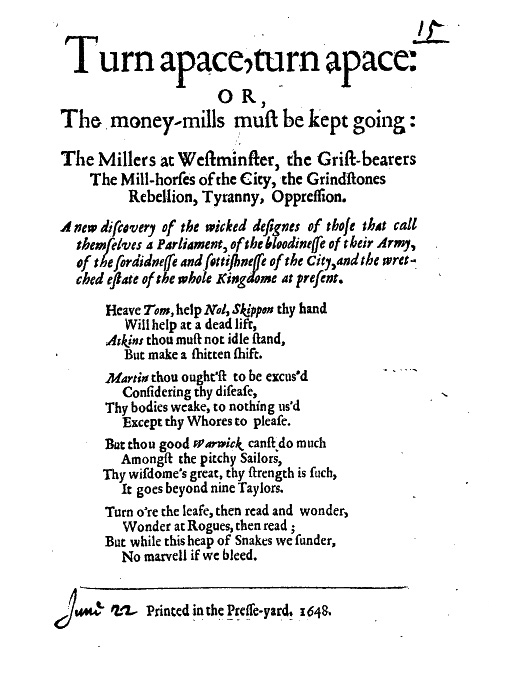

- [CORRECTED - 18.07.17 - 2 illegibles] T.144 (9.25) Anon., Turn apace, turn apace; or the money-mills must be kept going (22 June, 1648).

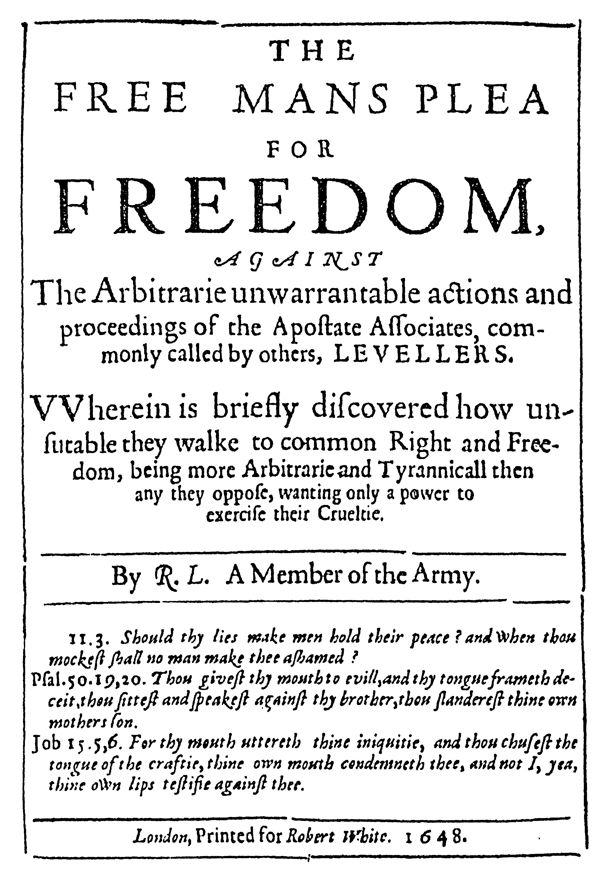

- [CORRECTED - 20.07.17 - 3 illegibles] T.145 (5.12) Anon., The Free Mans Plea for Freedom (18 May, 1648).

- The Free Mans Plea for Freedom

- A Postscript. To those private souldiers of the Armie

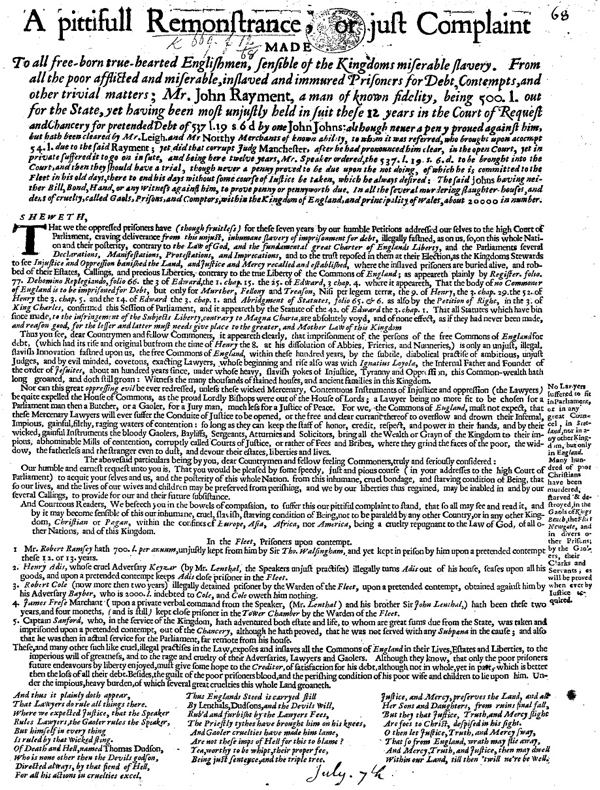

- [CORRECTED - 18.07.17 - 4 illegibles] T.146 (9.26) Anon., A Pittiful Remonstrance (7 July, 1648).

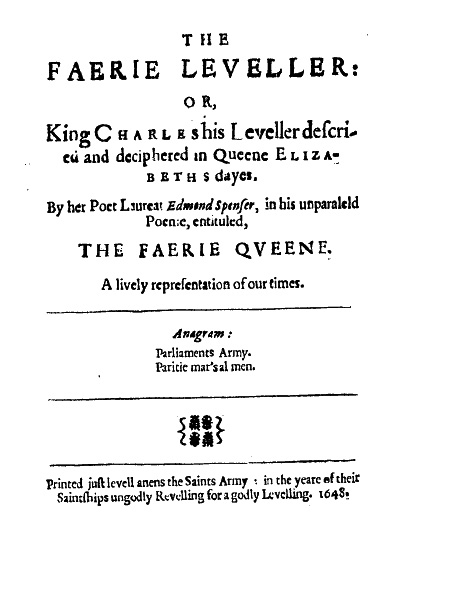

- [CORRECTED - 20.07.17 - 12 illegibles] T.147 (9.27) Anon., The Faerie Leveller (27 July, 1648).

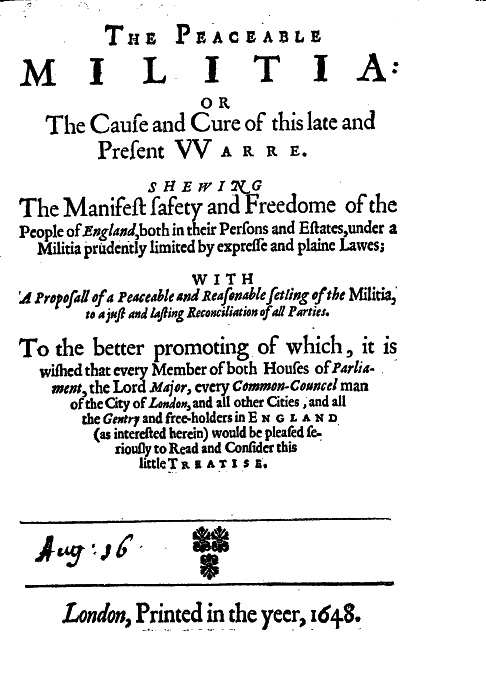

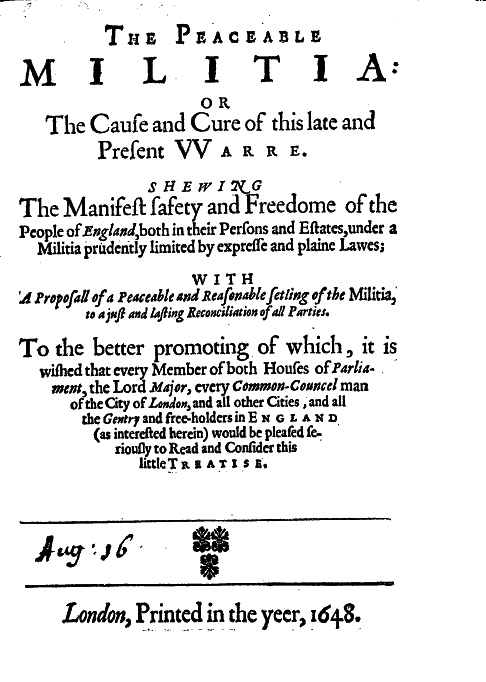

- [CORRECTED - 21.07.17 - 4 illegibles] T.148 (5.13) Anon., The Peaceable Militia (16 August, 1648).

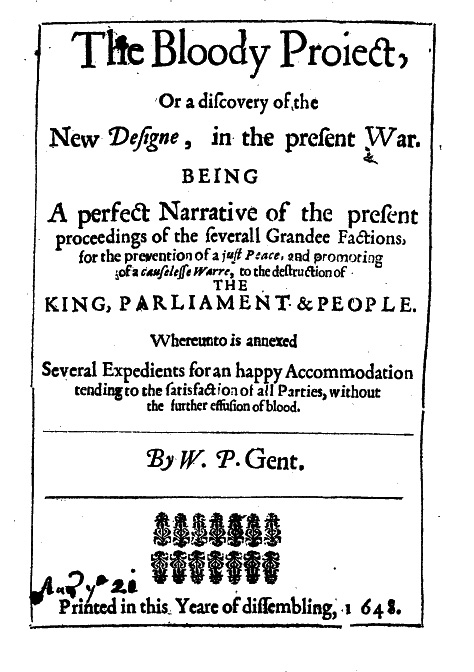

- [CORRECTED - 21.07.17 - 6 illegibles] T.149 (5.14) [William Walwyn], The Bloody Project (21 August, 1648).

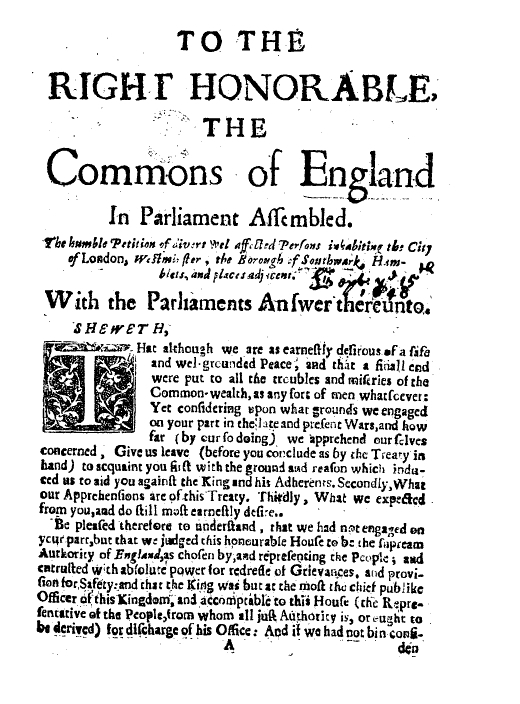

- [CORRECTED - 6.07.16 - 0 illegibles] T.150 (5.15) Anon., The Petition of 11 September, 1648 (11 Septyember, 1648)

- [Duplicate: UNCORRECTED - 2 illegibles] T.151 (9.28) [John Lilburne], To the Right Honourable, and supreame Authority of this Nation (March, 1647).

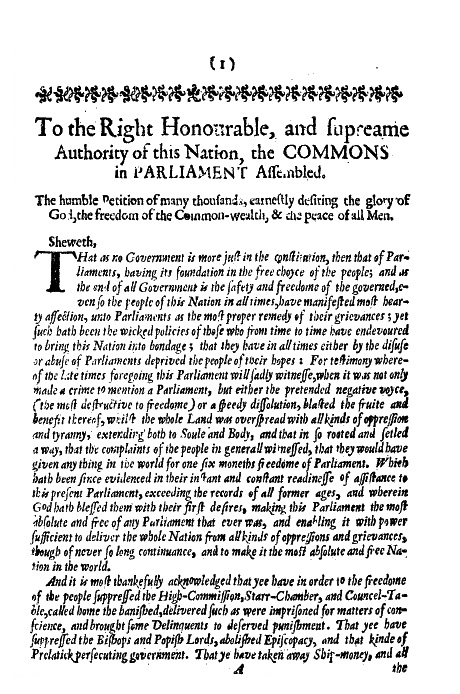

- To the Right Honourable, and supreame Authority of this Nation, the COMMONS in PARLIAMENT Assembled. The humble Petition of many thousands, earnestly desiring the glory of God, the freedom of the Common-wealth, & the peace of all Men ("THat as no Government is more just in the constitution, then that of Parliaments")

- To the Right Honourable, the Commons of England assembled in Parliament. The humble Petition of divers well-affected Citizens ("THat as the opressions of this Nation, in times fore-going this Parliament, were so numerous & burthensome"

- To the Honourable Committee of Parliament, sitting in the Queenes &illegible; as Westminster, Colonell Lee being Chair-man. The Humble Certificate of divers persons interessed in, and avouching the Petition lately referred to this Committee by the Right Honourable House of Commons ("THat the Petition (entituled, The humble Petition of many thousands, earnestly desiring the glory of God, the freedome of the Common-wealth, and the peace of all men, and directed to the Right Honourable, and supreame authority of this Nation, the Commons assembled in Parliament) is no scandalous or seditions Paper (as hath been unjustly suggested) but a reall Petition")

- To the Right Honourable, the Commons of England assembled in PARLIAMENT. The humble Petition of divers well-affected people in and about the City of LONDON ("THat as the authority of this Honourable House is intrusted by the people for remedy of their grievances")

- To the Right Honourable the Commons of England Assembled in Parliament. The humble Petition of many thousands of well-affected people ("THat having seriously considered what an uncontroulled liberty hath generally been taken")

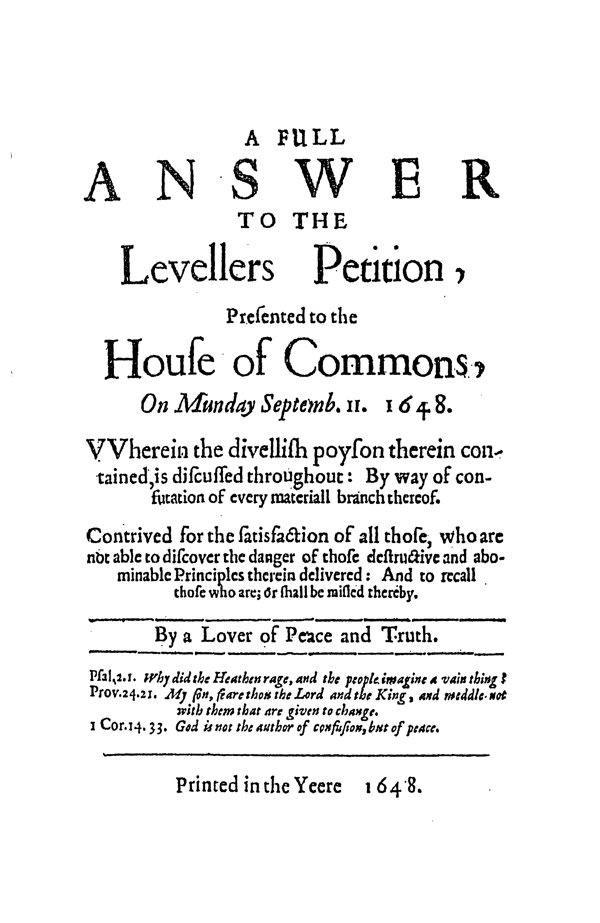

- [CORRECTED - 21.07.17 -] T.152 (5.16) Anon., A Full Answer to the Levellers Petition (11 September, 1648).

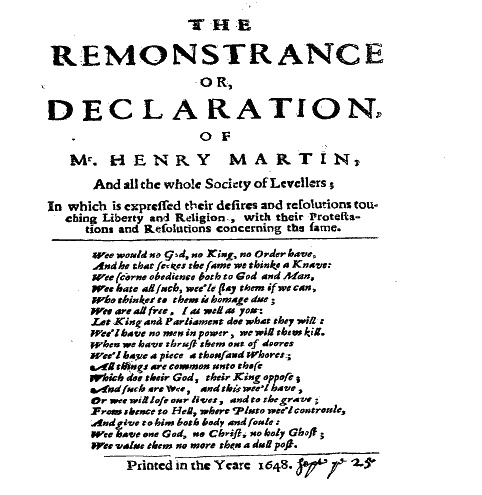

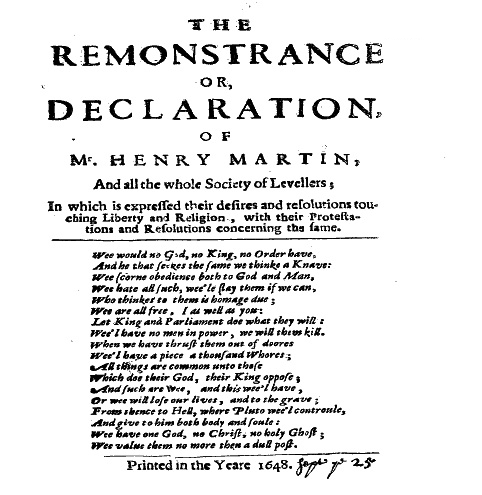

- [CORRECTED - 12.07.16] T.153 (5.17) Anon., The Remonstrance or, Declaration, of Mr. Henry Martin (25 September, 1648).

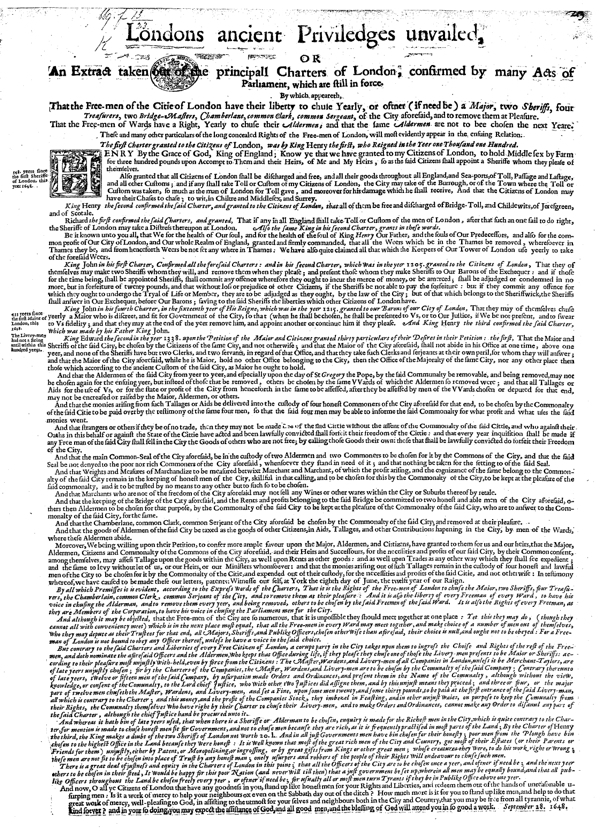

- [CORRECTED - 21.07.17 -- 1 illegible] T.154 (5.18) [City of London], Londons Ancient Priviledges Unvailed (28 September, 1648).

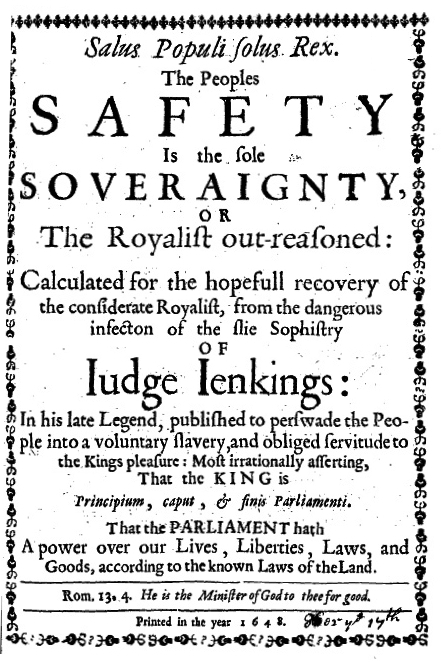

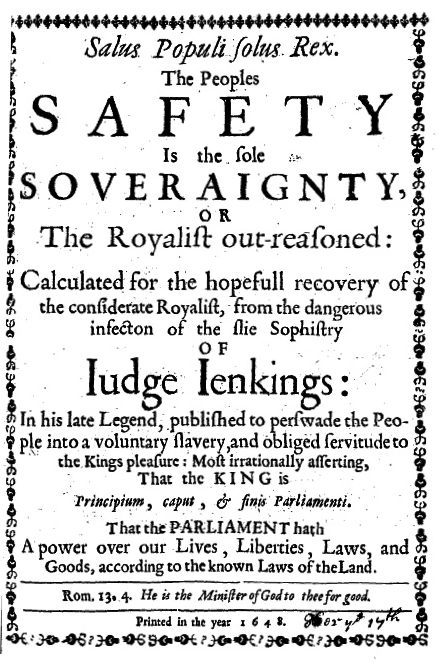

- [CORRECTED - 24.07.17 -- 2 illegibles] T.155 (5.19) Anon., Salus Populi Solus Rex. The Peoples safety is the sole Soveraignty (17 October, 1648).

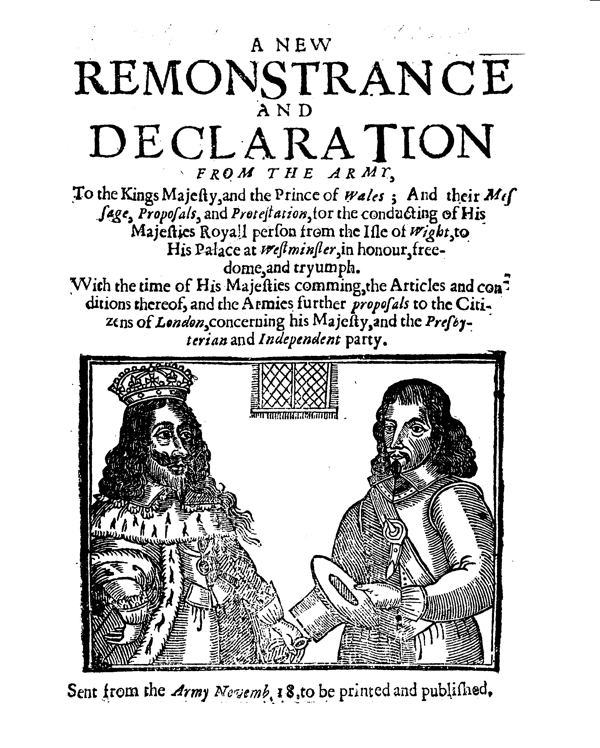

- [CORRECTED - 31.07.17 - 7 illegibles] T.156 (5.20) Oliver Cromwell, A New Remonstrance and Declaration from the Army (18 November, 1648).

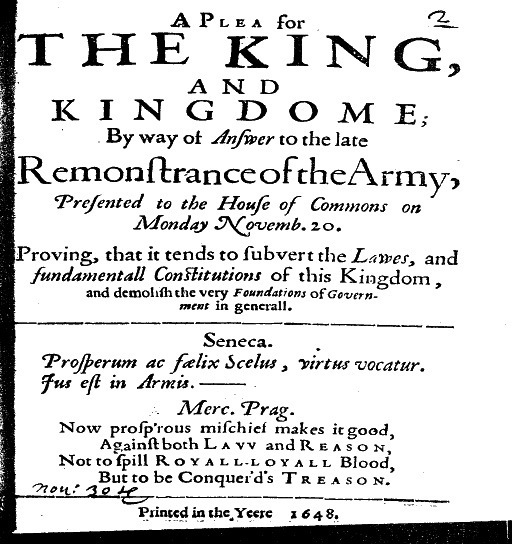

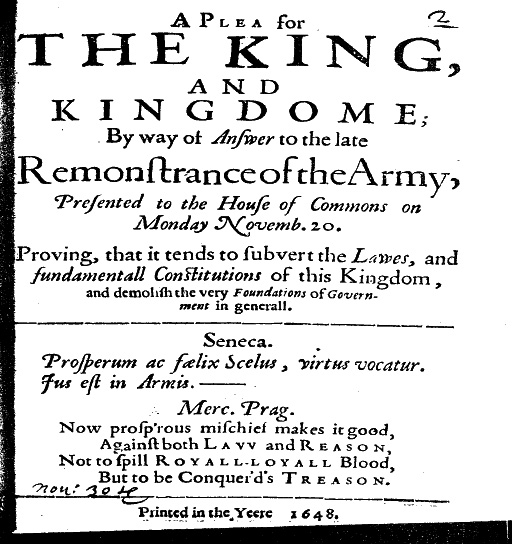

- [CORRECTED - 01.08.17 - 48 illegibles] T.157 (9.29) Marchamont Nedham, A Plea for the King (20 November, 1648).

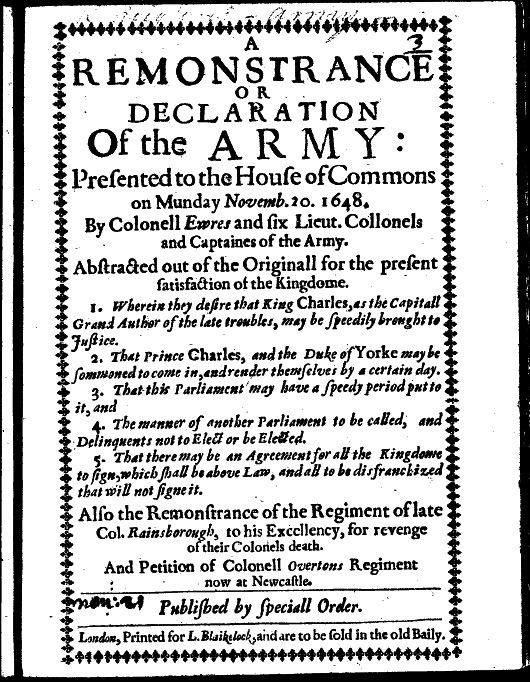

- [CORRECTED - 14.07.17 - 10 illegibles] T.158 (9.30) Anon., A Remonstrance or Declaration of the Army (20 November, 1648).

- A Remonstrance or Declaration of the Army, presented to the House on Munday Novemb. 20. 1648. By Col. Ewres, and ?? Lieutenant-Colonels and Captaines of the Army.

- Remonstrance of the regiment of the late Col. Rainsborough to his Excellency, for revenge of their Colonells death.

- The humble Petition of the Officers of Colonell Overtons Regiment, now in the Garrison of Berwick.

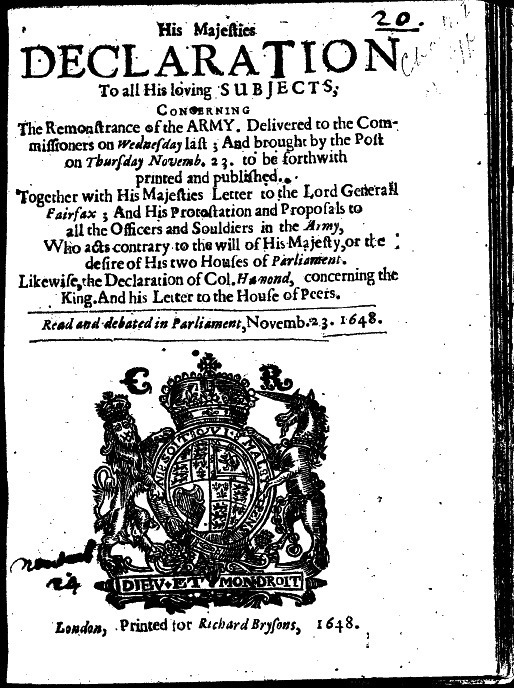

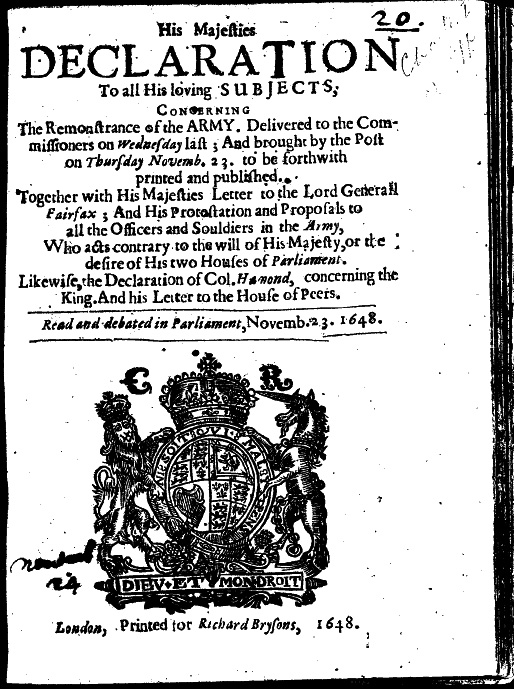

- [CORRECTED - 14.07.17 -] T.159 (9.31) Charles I, His Majesties Declaration to all His loving Subjects (23 November, 1648).

- His Majesties DECLARATION Concerning the ARMY, AND His Resolution touching their late Remonstrance, to proceed by the way of Charge against His Royall person (22 Nov. 1648)

- The Proposals of the parliament touching the Demands of the Army

- The Declaration of the Citizens of London, concerning the Demands of the Army

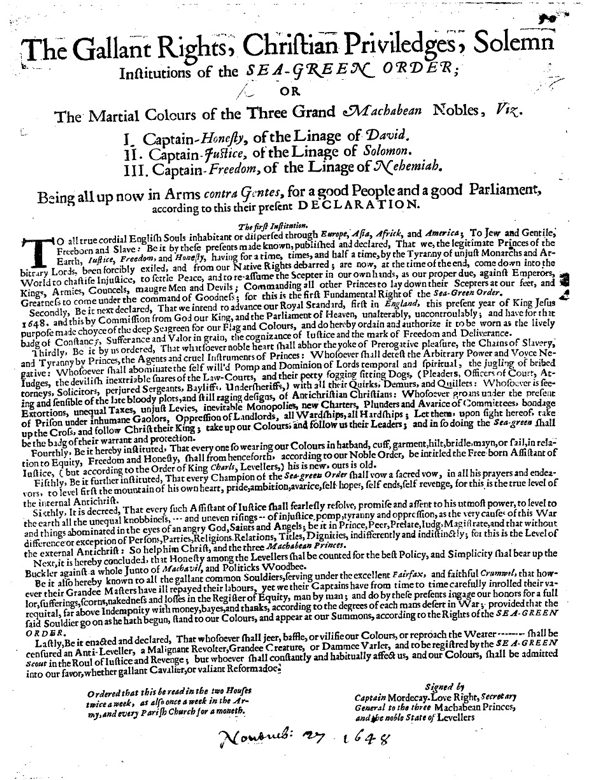

- [CORRECTED - 14.07.17 -] T.160 (9.32) Anon., The Gallant Rights, Christian Priviledges, Solemn Institutions of the Sea-green Order (27 November, 1648).

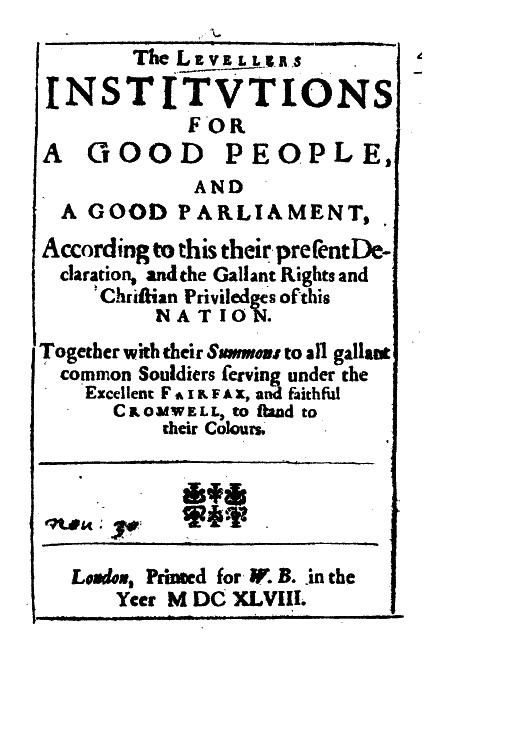

- [CORRECTED - 14.07.17 - 1 illegible] T.161 (9.33) Anon., The Leveller Institutions for a Good People (30 November, 1648).

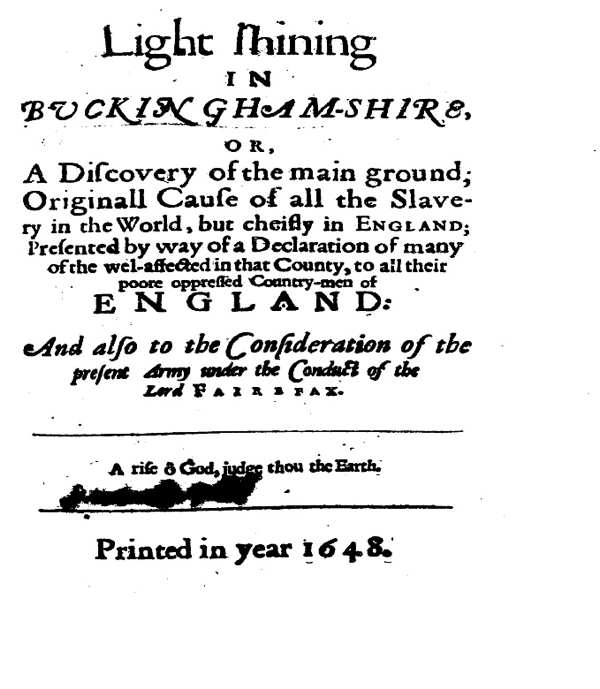

- [CORRECTED - 01.08.17 - 23 illegibles] T.162 (5.21) Anon., Light shining in Buckingham-shire (5 December, 1648).

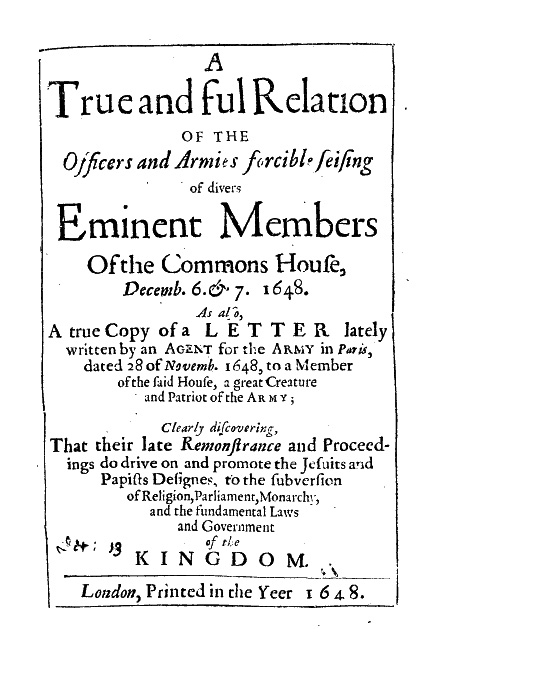

- [CORRECTED - 02.08.17 -] T.163 (5.22) [William Walwyn], A True and Ful Relation (6 December, 1648).

- A true Narrative of the Officers and Armies forcible seizing and suspending of divers eminent Members of the Commons House, December 6, & 7. 1648.

- The names of the imprisoned Members.

- A true Copie of a Letter written by an Independent Agent for the Army

- [CORRECTED - 02.08.17 - 2 illegibles] T.164 (5.23) King Charles I, Oliver Cromwell, The Kings Majesties Message (6 December, 1648).

- A LETTER From Lieut. Generall CRUMWEL To the Citizens of London (2 Dec, 1648)

- A Message from the King concerning the Army.

- A Declaration of the proceedings in Parliament, concerning the KING.

- His Maiesties Declaration upon his coming into Wiltshire.

- [CORRECTED - 02.08.17 - 48 illegibles] T.165 (9.34) Anon., Women Will Have their Will (12 December, 1648).

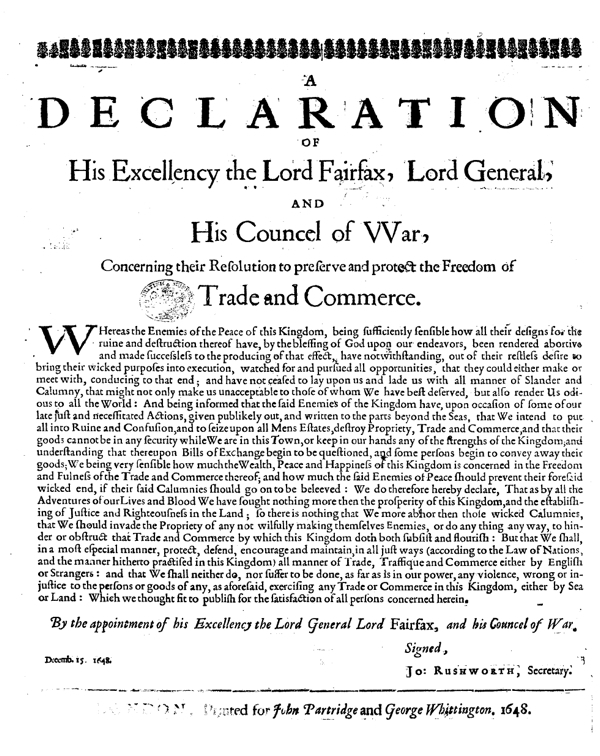

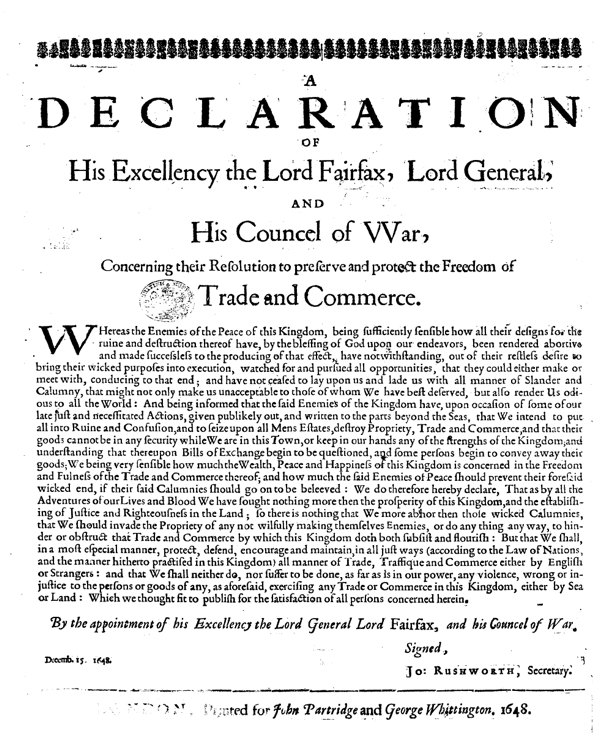

- [CORRECTED - 02.08.17 -] T.166 (5.24) John Rushworth, Thomas Fairfax , A Declaration Concerning the Freedom of Trade and Commerce (15 December, 1648).

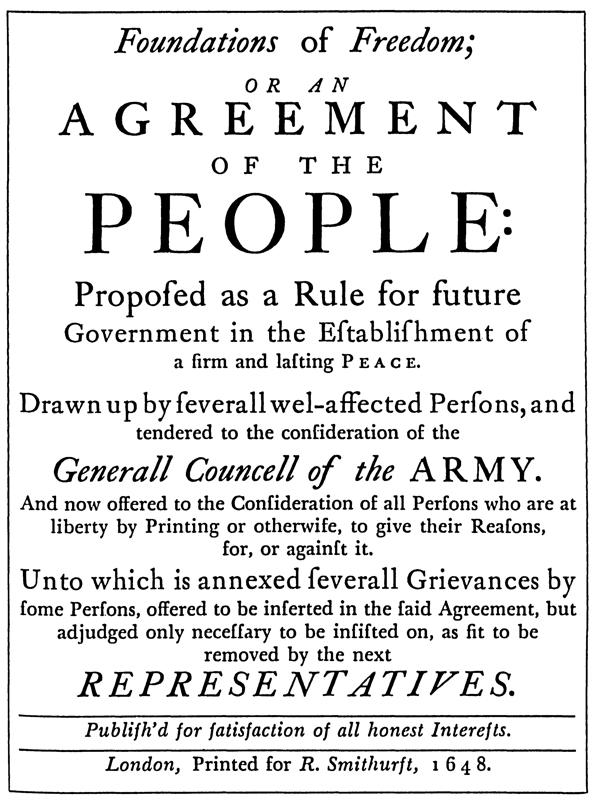

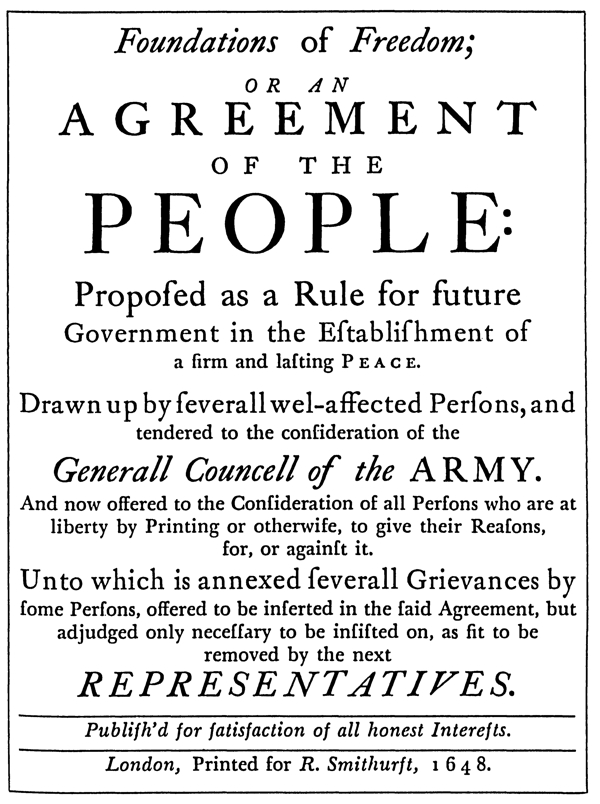

- [CORRECTED - 14.01.16 -] T.167 (5.25) Anon., Foundations of Freedom, Or An Agreement of the People (15 December, 1648).

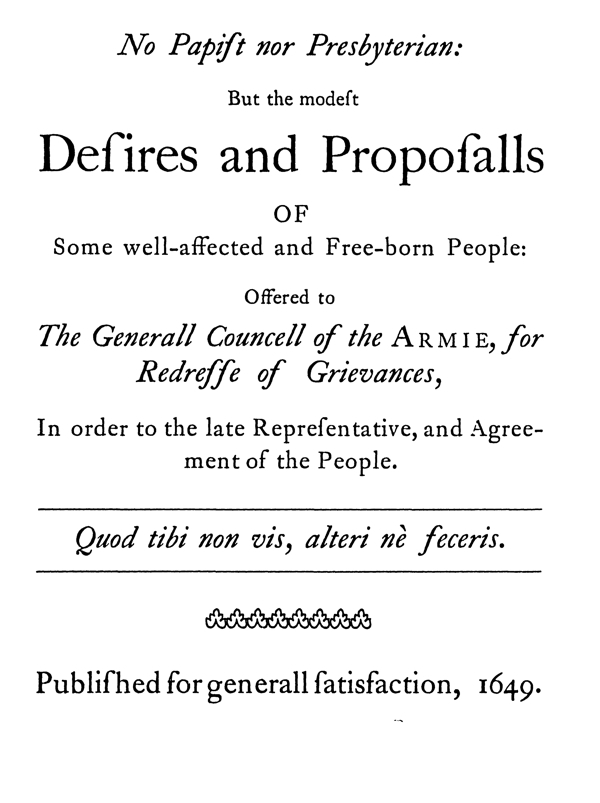

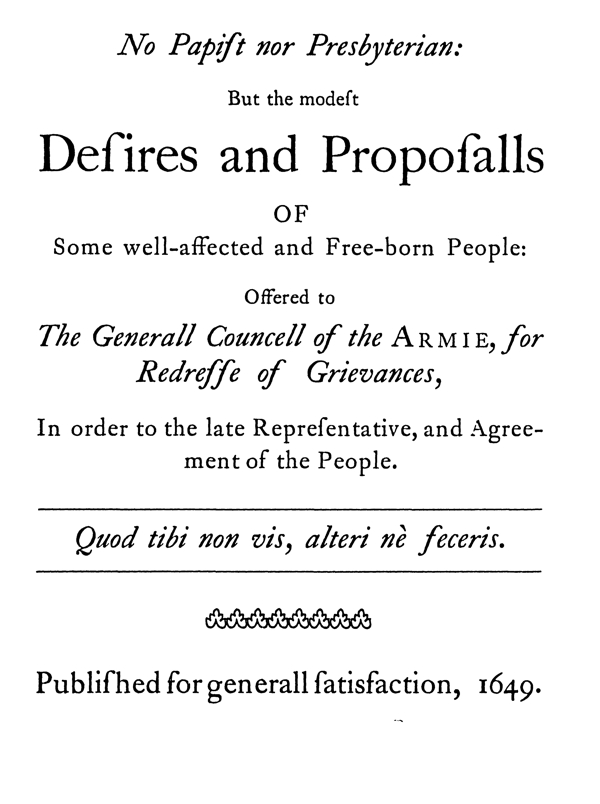

- [CORRECTED - 02.08.17 -] T.168 (5.26) [William Walwyn], No Papist Nor Presbyterian (21 December, 1648).

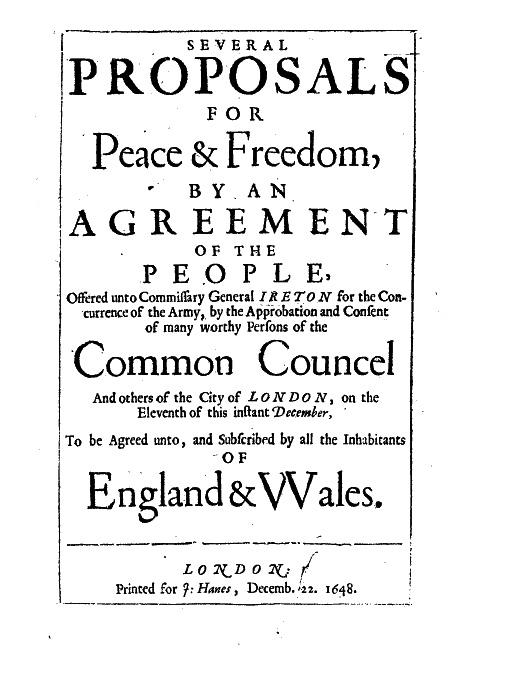

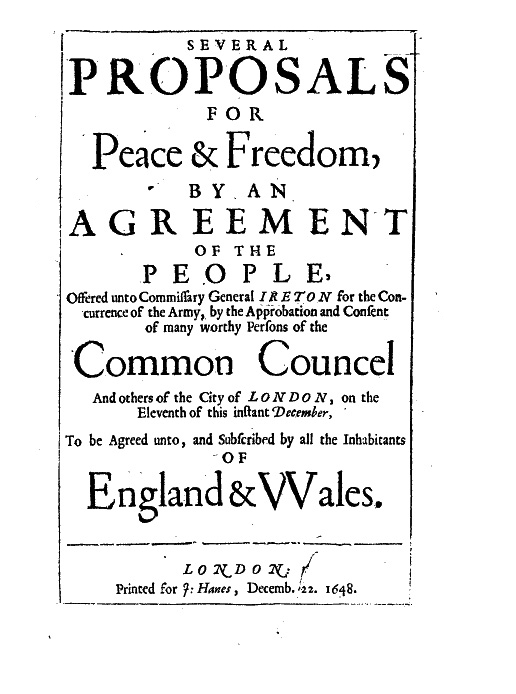

- [CORRECTED - 02.08.17 - 1 illegible] T.169 (5.27) [Lieut. Col. John Jubbes], Several Proposals for Peace & Freedom (22 December, 1648).

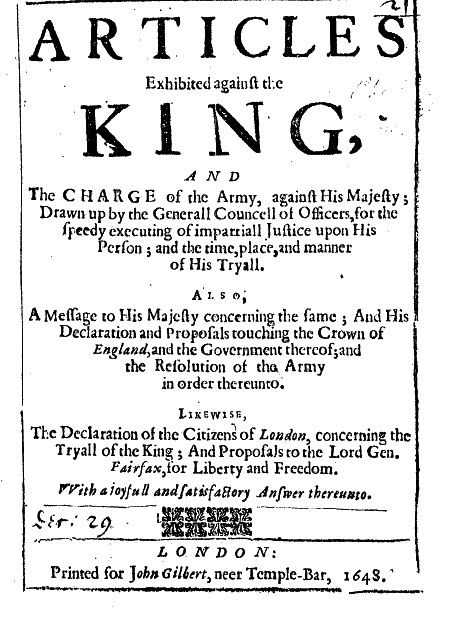

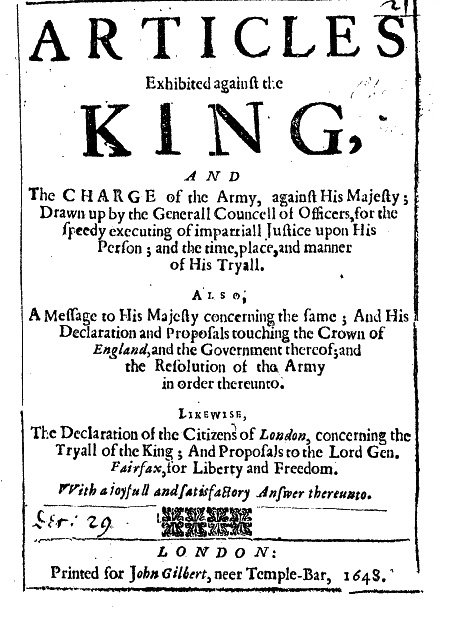

- [CORRECTED - 02.08.17 -] T.170 (5.28) Anon., Articles exhibited against the King (28 December, 1648).

- The gallant RESOLVTION Of the Lord Generall FAIRFAX

- His Majesties Proposals touching the Crown of England.

- A Remonstrance from Gloucester-shire.

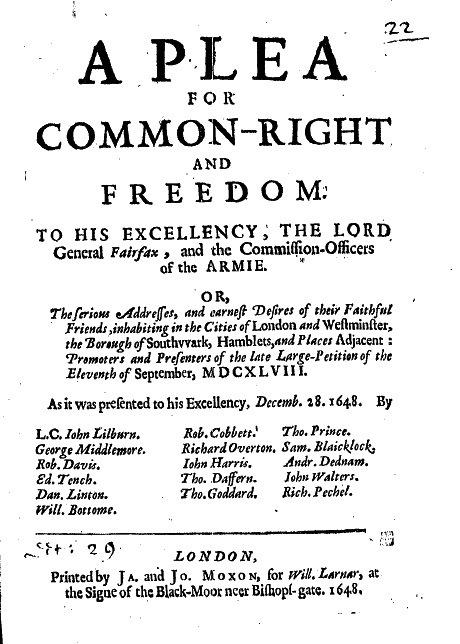

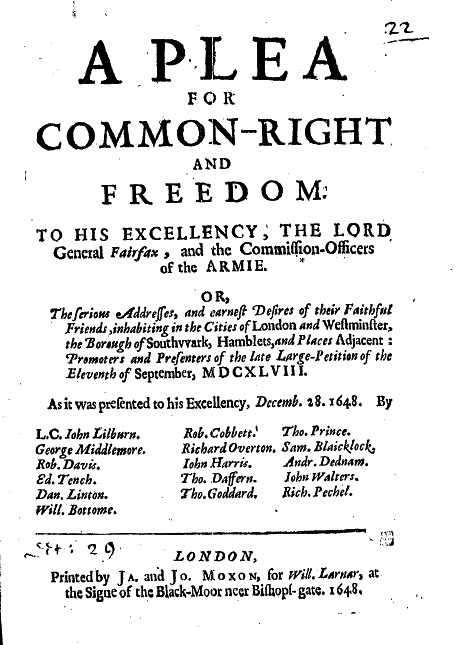

- [CORRECTED - 21.08.17 -] T.171 (5.29) John Lilburne, A Plea for Common-right and Freedom (28 December, 1648).

- [PREVIOUSLY CORRECTED - RECHECK] T.172 (5.30) [Several Hands], The Whitehall Debates (December, 1648 - January, 1649).

- Generall Councell, Dec. 14, 1648.

- Orders for the discussing of this Question.

- General Councill. att Whitehall. 14 December. 1648.

- Councell of War held at Whitehall the 15th of December 1648.

- [Letter to Lt. Col. Cobbett and others.]

- Generall Councell. Westminster Dec. 16 1648.

- Whitehall Dec. 18 1648. Generall Councell.

- Whitehall December the 19th 1648.

- [Sir George Booth to the inhabitants of Cheshire.]

- [Captain Richard Haddock to Mr John Rushworth.]

- Whitehall Dec. 21 1648. Generall Councell.

- [Letter to Col. Harrison.]

- [Cromwell and Ireton to Col. Whitchcott.]

- General Council. (Dec. 23)

- [Ld. Fairfax to Col. Thomlinson.]

- Whitehall Dec. 26 1648. Generall Councell.

- General Council att Whitehall 29 December 1648.

- Whitehall Dec. 29 1648. Generall Councell.

- Some Remarkable Passages out of the Countie of Hereford and Southwales concerning Sir Robert Harley and other

- Members of the Howse of Comons c.a

- Charge against Mr. Thomas Smith. (Jan. 4, 1648)

- General Councill 5 Jan. 1648 att Whitehall.

- Generall Councill. (6 Jan. 1648)

- Generall Council. 8 Jan. 1648.

- Generall Councill. (10 Jan. 1648)

- Generall Councill. (11 Jan. 1648)

- Generall Councill. (13 Jan. 1648)

Introductory Matter↩

[Insert here]:

- intro image and quote

- Publishing History

- Introduction to the Series

- Publishing and Biographical Infromation

- Key to the Naming and Numbering of the Tracts

- Copyright and Fair Use Statement

- Further Reading and info

Key (revised 21 April 2016)↩

T.78 [1646.10.12] (3.18) Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646).

Tract number; sorting ID number based on date of publication or acquisition by Thomason; volume number and location in 1st edition; author; abbreviated title; approximate date of publication according to Thomason.

- T = The unique "Tract number" in our collection.

- When the month of publication is not known it is indicated thus, 1638.??, and the item is placed at the top of the list for that year.

- If the author is not known but authorship is commonly attributed by scholars, it is indicated thus, [Lilburne].

- Some tracts are well known and are sometimes referred to by another name, such as [“The Petition of March”].

- For jointly written documents the authoriship is attributed to "Several Hands".

- Anon. means anonymous

- some tracts are made up of several separate parts which are indicated as sub-headings in the ToC

- The dating of some Tracts is uncertain because the Old Calendar (O.S.) was still in use.

- (1.6) - this indicates that the tract was the sixth tract in the original vol. 1 of the collection.

- Tracts which have not yet been corrected are indicated [UNCORRECTED] and the illegible words are marked as &illegible;. Some tracts have hundreds of illegible words and characters.

- As they are corrected against the facsimile version we indicate it with the date [CORRECTED - 03.03.16]. Where the text cannot be deciphered it is marked [Editor: illegible word].

- After the corrections have been made to the XML we wil put the corrected version online in the main OLL collection (the "Titles" section).

- [elsewhere in OLL] the document can be found in another book elsewhere on the OLL website.

Copyright and Fair Use Statement↩

The texts are in the public domain.

This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Editorial Matter↩

[Insert here]:

- Editor's Introduction to this volume

- Chronology of Key Events

Tracts from 1648 (Volume 5)

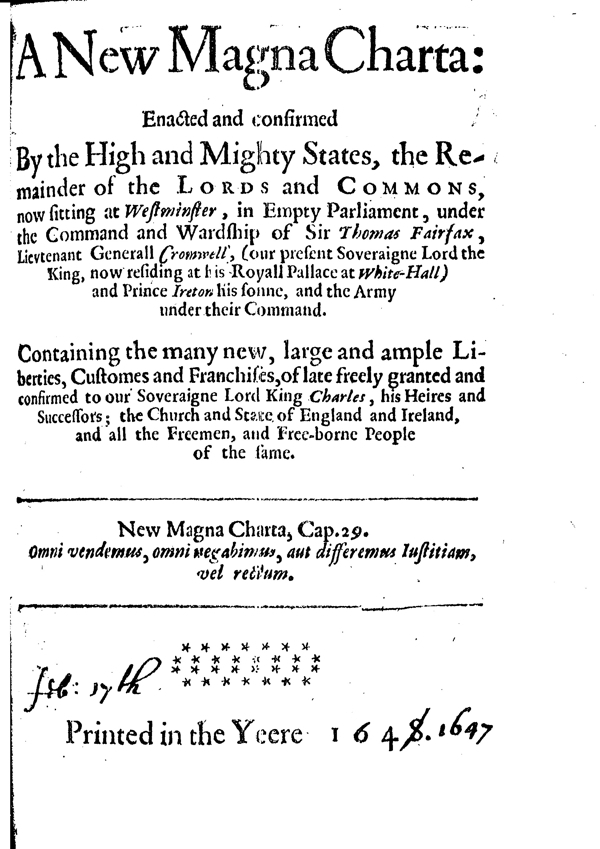

T.126 (5.1) William Prynne, A New Magna Charta (1 January, 1648).↩

Corrections completed:- Corrections to HTML: 24 Aug. 2016

- Corrections to XML: date

Bibliographical Information

ID NumberT.126 [1648.01.01] (5.1) William Prynne, A New Magna Charta (1 January, 1648).

Full titleWilliam Prynne, A New Magna Charta: Enacted and confirmed By the High and Mighty States, the Remainder of the Lords and Commons, now sitting at Westminster, in Empty Parliament, under the Command and Wardship of Sir Thomas Fairfax, Lievtenant Generall Cromwell, (our present Soveraigne Lord the King, now residing at his Royall Pallace at White-Hall) and Prince Ireton his sonne, and the Army under their Command. Containing the many new, large and ample Liberties, Customes and Franchises, of late freely granted and confirmed to our Soveraigne lord King Charles, his Heires and Successors; the Church and State of England and Ireland, and all the Freemen, and Free-borne People of the same.

New Magna Charta, Cap. 29. Omni vendemus, omni regabimus, aut differemus Iustitiam, vel rectum.

Printed in the yeere 1648.

Estimated date of publication1 January, 1648.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 593; Thomason E. 427. (15.).

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

A new Magna Charta.

FIrst for the honour of Almighty God, and in pursuance of the solemne League and Covenant which we made in the presence of Almighty God for the Reformation and defence of Religion, the honour and happinesse of the King, and the peace and safety of the three Kingdomes of England, Scotland, and Ireland, we have granted, and by this our present Charter have confirmed, That the Church of England shall be free to deny the perpetuall Ordinances of Jesus Christ, to countenance spreading heresies, cursed blasphemies, and generall loosenesse and prophanenesse, and that all Lawes and Statutes formerly made against the aforesaid offences for the punishment and restraining thereof shall be utterly repealed, that so all men may freely enjoy and professe what Religion soever they please without restraint: And we will that all Archbishops, Bishops, and their dependents shall be eternally suppressed, and all their Mannours, Lands and possessions sold to defray and advance the Publique Faith. That all Ministers shall be plundered and thrust out of their livings and freeholds by our Committee of plundering Ministers without Oath or legall tryall, upon bare informations of such of their Parishioners who are indebted to them for Tythes, or have any Kinsman to preferre to their livings. And to supply the want of Ministers, That all Officers, Souldiers, Coblers, Tinkers, and gifted Brethren and Sisters, shall freely preach, and propagate the Gospell to the people, and new dip and rebaptize them without punishment.

Item. We will that the Kings Majesties person be maintained, and his Authority preserved, by seizing his Person at Holdenby with a party of horse, and imprisoning him in the Army, indangering his life at Hampton Court, and by colour thereof conveighing him secretly into the Isle of Wight, removing from him all his Attendants, disposing of his Revenue, Children, Forts, Ships, Castles, and Kingdomes, and by this putting in execution these our Votes, That no more addresses be made from the Parliament to the King, nor any Letters or Message received from him: That it shall be Treason for any persons whatsoever to deliver any Message to the King, or receive any Messages or Letters from him, without leave from both Houses of Parliament: That a Committee draw up a Declaration to be published, to satisfie the Kingdome of the reason of passing these Votes, That so the world may beare witnesse with our consciences of our Loyalty, and that we have no thoughts or intentions to diminish His Majesties just power and greatnesse, according to the words of the solemne League and Covenant.

Item, We give and grant to the Freemen of the Realm these Liberties underwritten.

First, that no Sheriffes shall make due returnes of the Citizens and Burgesses elected to serve in Parliament, nor make due Elections of Knights, nor in convenient time, nor the ablest wisest, nor discreetest shall be returned, but all fraud and deceit shall be used in Elections, and persons not duly elected, nor elegible by Law shall be Members of the House of Commons, and those to be our sonnes, kindred, servants, officers and such as will comply with us.

Item, No Member shall sit in the House of Commons with freedome and safety that endeavours to settle Religion in the purity thereof, according to the Covenant, to mantaine the ancient and fundamentall Government of the Kingdome, or to preserve the Rights and Liberties of the Subject, or that layes hold on the first oportunity of procuring a safe and well-grounded peace in the three Kingdoms, or that keeps a good understanding between the two Kingdomes of England and Scotland, according to the grounds expressed in the solemne League and Covenant.

And whoever offends against this Article, we will that such Members be impeached of High Treason by the Army, suspended the House before any particular impeachment, forced to accuse themselves by stating their cases for want of an accuser, and witnesses to prove them criminall, and at the last cast out of the House without answer, hearing the evidence, or privity of those that elected them whose persons they represent.

Item, We grant, that neither we nor any by colour of Authority derived from us shall interrupt the ordinary course of Justice in the severall Courts and Judicatures of the Kingdome, nor intermeddle in causes of private interest otherwhere determinable, save onely our Committees of Indempnities, plundered Ministers, Complaints, Sequestrations, Excize and the Army, who shall judge and contradict the Lawes and Statutes of the Realme, vacate and repeale all Indictments, Verdicts, and Judgements given in Courts of Justice, imprison all manner of persons, and turne them out of their Freeholds, Estates, Goods, and Chattels without the lawfull judgement of their Peers, and against the fundamentall Lawes of the Land.

Item, we will and ordaine that the great and unusuall payments imposed upon the people, and the extraordinary wayes that were taken for procuring moneyes, shall (contrary to the trust reposed in us) be still burthensome, and daily increased more and more upon the people by our bare Votes and Ordinances, without the common consent by Act of Parliament; and in case of refusall, forcibly levyed by Troops of horse and souldiers, according to the law of decolled Strafford, of all which moneyes our selves and Members will be sole treasurers and disposers: Free-Quarter shall be still tolerated, and countenance given by us to the exactions and extortions of the souldiers, to whom we have granted an Ordinance of Indempnity for all murders, fellonies, rapes, robberies, injuries and trespasses committed by them, and all such offences as they shall commit, to the end they may protect us against the clamours and complaints of the oppressed people either by Sea or Land: and we ordaine, that all Free-men shall henceforth be tryed onely by Martiall and Committee Law, and impeached of new high Treason at our pleasure, to consiscate their estates to our Exchequer.

Item, We will that such persons as have done valiantly, and dealt faithfully in the Parliaments cause according to the Declaration of England and Scotland, shall be publikely disgraced and dishonoured, and without cause thrust from their commands and imployments both Civill and Martiall without pay, hearing conviction or reparation for their losses, and that the severall and respective Lievtenants, Governours, and old Garrison Souldiers of the Tower of London, Newcastle, Yorke, Bristoll, Plymouth, Glocester, Exeter, Chester, Pendennis Castle and the Isle of Wight be removed with disgrace by our new Generalissimoes meere arbitrary power, notwithstanding our former Votes and Ordinances for their particular settlement, and new mean seditious Sectaries of our confederacy put into their places.

Item, We will that a just difference be made between such persons as never departed from their Covenant and duty, and such as were detestable Newtralists and oppressours of the people, and to that end we will, that the Commission of the Peace be renewed at the pleasure of our flying Speakers, who are to provide, that such be omitted as agree not with the frame and temper of the Army and us their Lords and Commons sitting at Westminster, and others be added in their places who have complied with the enemy, and oppressed the people, and to that end we agree, that the Earle of Suffolke, Earle of Middlesex, William Lord Maynard, William Hicks, Knight and Baronet, John Parsons Knight, Richard Pigott Knight, Edward King Esquire, Thomas Welcome Esquire, and divers others be omitted, and that John Lockey, Thomas Welby, VVilliam Godfrey, Richard Brian, Sir Richard Earle Baronet, and others of that stamp be added, of whose integrity and faithfulnesse Quere.

Item, We will that for the perpetuall honour of the Lords and Barons of this Realme, whose Ancestors purchased for us with the expence of their lives and bloods from King John and Henry the third, the great Charter, that they shall from henceforth he impeached of High Treason, committed, imprisoned, and put out of the House of Peers, and forfeit their lives and estates to our disposing, if they defend that great Charter, the lives and Liberties of the Subjects and Parliament against a perfidious and rebellious Army, and us the fugitive Lords and Commons, who fled from our Houses to the Army without cause, and there entred into a trayterous Covenant and Ingagement, to live and die with the Army, and to destroy the faithfull Members that stayed behind at Westminster, and all the freedome of this and future Parliaments. And we will that henceforth there shall be no House of Peers, distinct from Commons, but that all Peers and Peerage be for ever abolished, and all great and rich mens estates levelled and made equall to their poorest neighbours, for the better reliefe and encouragement of the poor Saints.

Item, We will that the City of London shall have all her ancient Liberties and Customes in as full and ample manner as her Predecessors ever had, and for that end we will that the Army shall march in a Warlike manner towards that City, and passe like Conquerours in tryumph through the same. That all the Fortifications and Line about it shall be slighted and thrown downe, the Tower taken out of their hands, and put into our Generalls, and fortified to over-awe them; the Militia of the City changed and divided from that of Westminster, and Southwarke, the Lord Mayor, Recorder, Aldermen and some leading men of the Common Counsell, by crafty, sinister, and feigned informations, impeached of high Treason, and other great Misdemeanours imprisoned and disabled, and others by our appointment and nomination put into their places, and the Citizens and Common Counsell-men shall henceforth make no free Elections of Governours and Officers: That White-Hall, the Muse, Minories, Ely-house and other places shall be made Citadells, that the Posts and Chaines in the City and Suburbs be taken away, their Gates and Purcullices pulled downe, their Armes delivered into a common Magazine by our appointment, to disable them from all future possibility of selfe-defence, or disobedience to our imperiall commands, that so they may willingly deliver us up the remainder of their exhausted treasures and estates, when we see cause to require the same, and made as absolute Freemen for all their expence of treasure and blood in our defence, as our English Gally-slaves now are in Algier.

Item, We will that the command of the Navy and all ships at Sea, for the honour of this Nation and our owne, be committed into the hands and government of a Vice-Admirall, (without and against the consent of the Lords) of late but a Skippers Boy, a common Souldier in Hull, a Leveller in the Army, impeached by the Generall for endeavouring to raise a mutiny at the late Rendevouz, and since that taken with a Whore in a Bawdy house, who rode downe in triumph to the Downes to take possession of his place in a Coach and foure horses, with a Trumpeter and some Troopers riding before and after it, sounding the Trumpet in every Towne and Village as they passed, to give notice of his new Excellencies arrivall, and make the common people vaile Bonnet, and strike sale to his Coach, and at his late returne from the Isle of Wight to the Downes was rowed from the ship to the Towne of Deale with the Ensigne in the sterne, the Boatswaine and all the Rowers bare headed, like so many Gally-slaves, (a new kind of state which never any Lord-Admirall in England, though the greatest Peer, yet tooke upon him, but the King onely:) and to maintaine this new pompe and state of his we will and ordain, that all Merchants, as well Natives as Forraigners, shall pay such new Customes, Impositions, and Excize for all manner of goods and Merchandize whatsoever imported, or exported, as we in our arbitrary wisdomes shall judge meet, under paine of forfeiture of all their said goods and Merchandize, and such other penalties as we shall impose.

Item, We will and ordaine for the ease and reliefe of the almost famished poore in these times of dearth and decay of Trade, that Excize shall still be paid by them, and every of them for every drop of small beer they drinke, and for all oyles, dying stuffes, and Mercers wares they shall have occasion to use about their Trades and Manufactures, and that the lusty young souldiers, who are able to worke and get their livings by the sweat of their browes, shall ramble abroad through all the Kingdome, and like so many sturdy rogues, take Free-quarter for themselves, horses and companions from place to place, refusing to work, shall eat up all the provisions in Gentlemens, Yeomens, Clothyers, and other rich mens houses, who formerly relieved the impotent poore with their Almes, and the able with work.

Item, We will that William Lenthall our Speaker for the time being, shall have a Monopoly and plurality of all kind of Officers, for the maintenance of his state and dignity, and recompence of his infidelity, in the deserting the true House of Commons, notwithstanding the selfe-denying Ordinance to the contrary, and to this end we ordaine, that he shall be our perpetuall Speaker, and eternally take five pounds for every Ordinance that passeth the Commons House, with all other incident (new exacted) fees and gratuities; that he shall with this his office enjoy the custody and profits of the great Seale of England, the Dutchy of Lancaster, together with the Mastership of the Rolls, and as many other places as we shall be able to conferre upon him or his sonne; and that his honoured brother Sir John Lenthall for his great affection to and care of the Subjects Liberties committed to his custody, shall have free licence to suffer what prisoners he pleaseth to escape out of prison, and Sir Lewis Dives though Voted by us to be arraigned and tryed for high Treason this Terme, and all persons lying in execution for debts to goe and lie abroad at their owne houses, and make escapes at pleasure to the defrauding of Creditors, without being prosecuted, or put out of his office for the same, provided they alwayes give him a good gratuity for this their liberty of escape.

Item, We will that our distressed Brethren in Ireland may enjoy the benefit of this our new great Charter, and all the liberties therein comprized, and that by vertue thereof the supplies, reliefs, men, moneyes, and the monethly Tax of sixty thousand pounds designed for them, shall be totally interrupted, misimployed, and diverted by King Crumwell and Prince Jreton his son-in-law, to maintaine, pay and recruit their Supernumeraries and the Army here: That the noble and valiant Lord Inchequin who hath done such gallant service against the Rebells, shall be accused and blasted in both our Houses and Pamphlets, and mercenary Diurnall men for a Traytor, and Confederate with the Rebells, by the Lord Liste and his confederates, who wears much of Irelands imbezelled treasure on his back, and hath much more of it in his purse, taking no lesse then 10.l. or 15.l. a day, as Lord Deputy of that Realme, onely for riding about London streets in his Coach in state, and victorious honest Col. Jones discountenanced, discouraged, and both of them removed this Spring from their commands, to advance the Independent cause, and godly party in that Realme.

Lastly, all these new Customes and Liberties aforesaid, which we have granted to be holden in our Realmes of England and Ireland, as much as appertaineth to us we shall observe: and all men of these Realmes, as well Nobles as Commons, shall enjoy and observe the same against all persons in likewise. And for this our Gift and Grant of these Liberties, the Nobles and Commons are become our men from this day forward, of life and limb, and of earthly worship, and unto us shall be slaves and vassalls for ever; and we have granted further, that neither we nor any of us shall procure or do any thing, whereby all or any the Liberties in this Charter contained, shall be ever hereafter infringed or broken: and further we ordaine, that our Postmaster Edmund Prideaux, one of our fugitive & Army-ingaged Members, who by fraud got into that office, and keeps it by force against common right, do send Posts with Copies of this our Charter into all Counties, Cities and Places of our Dominions, for recompence of which service he shall still conciously enjoy that office, and that our Sheriffs, Committees, and new-made Justices cause the same to be speedily published accordingly in all our Countrey-Courts, these being our witnesses to this Charter.

William Lawd L. Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Earl of Strafford,

Sir John Hotham Knight, Governour of Hull, Lievtenant-Generall John Hotham,

All foure beheaded by our command at the Tower Hill for the breach of old Magna Charta and trecherie.

Nathanael Fines, condemned to lose his head by a Councell of War for delivering up Bristoll to our enemies, by us to be one of the Grand Committee forthe safety of this and yet spared Kingdome and Ireland, instead of the exploded Scotch Commissioners.

FINIS.

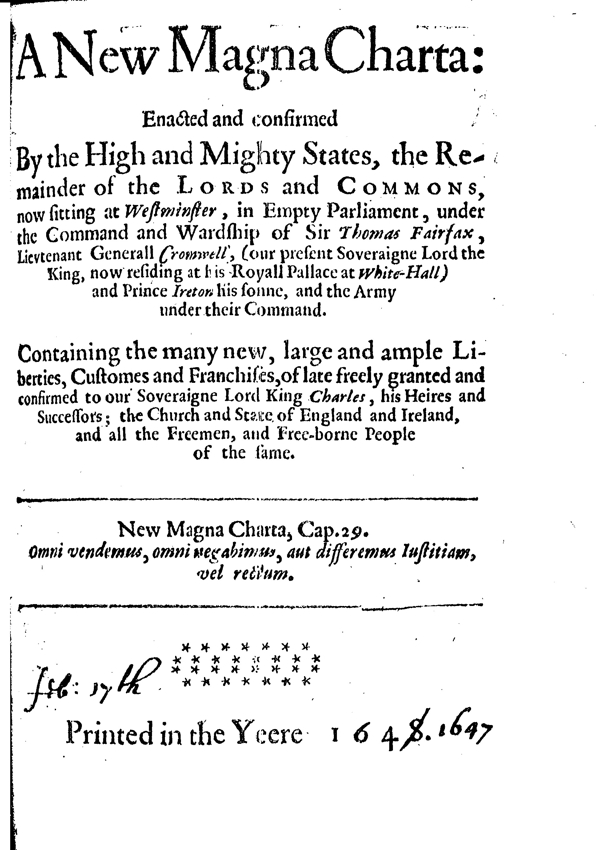

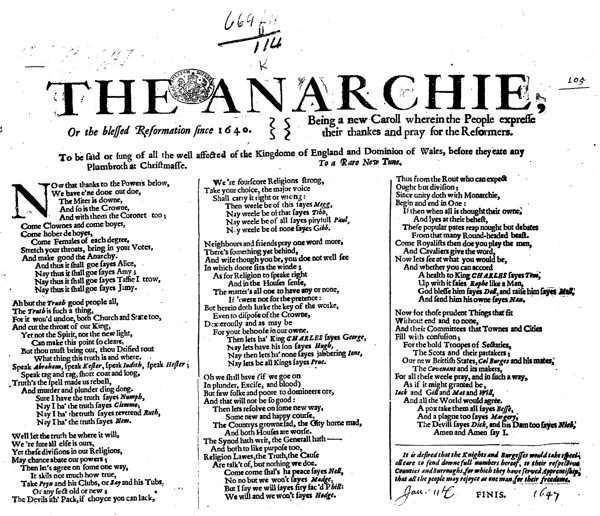

T.127 (9.20) Thomas Jordan, The Anarchie or the blessed Reformation since 1640 (11 January, 1648).↩

Corrections completed:- Corrections to HTML: 24 Aug. 2016

- Corrections to XML: date

Local JPEG TP Image

Bibliographical Information

ID NumberT.127 [1648.01.01] (9.20) Thomas Jordan, The Anarchie or the blessed Reformation since 1640 (11 January, 1648).

Full titleThomas Jordan, The Anarchie or the blessed Reformation since 1640. Being a new Caroll wherein the People expresse their thankes and pray for the Reformers. To be said or sung of all the well affected of the Kingdome of England and Dominion of Wales, before they eate any Plumbroth at Christmasse. To a Rare New Tune.

Estimated date of publication11 January, 1648.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 584; Thomason 669. f. 11. (114.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

NOw that thanks to the Powers below,

We have e’ne done our doe,

The Miter is downe,

And so is the Crowne,

And with them the Coronet too;

Come Clownes and come boyes,

Come hober de hoyes,

Come Females of each degree,

Stretch your throats, bring in your Votes,

And make good the Anarchy.

And thus it shall goe sayes Alice,

Nay thus it shall goe sayes Amy;

Nay thus it shall goe sayes Taffie I trow,

Nay thus it shall goe sayes Jamy.

Ah but the Truth good people all,

The Truth is such a thing,

For it wou’d undoe, both Church and State too,

And cut the throat of our King,

Yet not the Spirit, nor the new light,

Can make this point so cleare,

But thou must bring out, thou Deified rout

What thing this truth is and where.

Speak Abraham, speak Kester, speak Iudith, speak Hester;

Speak tag and rag, shore coat and long,

Truth’s the spell made us rebell,

And murder and plunder ding dong.

Sure I have the truth sayes Numph,

Nay I ha’ the truth sayes Clemme;

Nay I ha’ the truth sayes reverend Ruth,

Nay I ha’ the truth sayes Nem.

Well let the truth be where it will,

We’re sure all else is ours,

Yet these divisions in our Religions,

May chance abate our powers;

Then let’s agree on some one way,

It skils not much how true,

Take Pryn and his Clubs, or Say and his Tubs,

Or any sect old or new;

The Devils ith’ Pack, if choyce you can lack,

We’re fourscore Religions strong,

Take your choice, the major voice

Shall carry it right or wrong:

Then weele be of this sayes Megg,

Nay weele be of that sayes Tibb,

Nay weele be of all sayes pityfull Paul,

Nay weele be of none sayes Gibb.

Neighbours and friends pray one word more,

There’s something yet behind,

And wise though you be, you doe not well see

In which doore sits the winde;

As for Religion to speake right

And in the Houses sense,

The matter’s all one to have any or none,

If ’twere not for the pretence:

But herein doth lurke the key of the worke,

Even to dispose of the Crowne,

Dexterously and as may be

For your behoofe in our owne.

Then lets ha’ King CHARLES sayes George,

Nay lets have his son sayes Hugh,

Nay then lets ha’ none sayes jabbering Ione,

Nay lets be all Kings sayes Prue.

Oh we shall have (if we goe on

In plunder, Excise, and blood)

But few folke and poore to domineere ore,

And that will not be so good:

Then lets resolve on some new way,

Some new and happy course,

The Countrys growne sad, the City horne mad,

And both Houses are worse.

The Synod hath writ, the Generall hath—

And both to like purpose too,

Religion Lawes, the Truth, the Cause

Are talk’t of, but nothing we doe.

Come come shal’s ha peace sayes Nell,

No no but we won’t sayes Madge,

But I say we will sayes firy fac’d Phill:

We will and we won’t sayes Hedge.

Thus from the Rout who can expect

Ought but division;

Since unity doth with Monarchie,

Begin and end in One:

If then when all is thought their owne,

And lyes at their behest,

These popular pates reap nought but debates

From that many Round-headed beast.

Come Royalists then doe you play the men,

And Cavaliers give the word,

Now lets see at what you would be,

And whether you can accord

A health to King CHARLES sayes Tom,

Up with it saies Raphe like a Man,

God blesse him sayes Doll, and raise him sayes Mall,

And send him his owne sayes Nan.

Now for those prudent Things that sit

Without end and to none,

And their Committees that Townes and Cities

Fill with confusion;

For the bold Troopes of Sectaries,

The Scots and their partakers;

Our new Brittish States, Col Burges and his mates,

The Covenant and its makers,

For all these weele pray, and in such a way,

As if it might granted be,

Iack and Gill and Mat and Will,

And all the World would agree.

A pox take them all sayes Besse,

And a plague too sayes Margery,

The Devill sayes Dick, and his Dam too sayes Nick,

Amen and Amen say I.

It is desired that the Knights and Burgesses would take especiall care to send downe full numbers hereof, to their respective Counties and Burroughs, for which they have served Apprentiship, that all the people may rejoyce as one man, for their freedome.

FINIS.

T.128 (5.2) William Prynne, The Petition of Right of the Free-holders and Free-men (8 January, 1648)↩

Corrections completed:- Corrections to HTML: 24 Aug. 2016

- Corrections to XML: date

OLL Thumbs TP Image

Local JPEG TP Image

Bibliographical Information

ID NumberT.128 [1648.01.08] (5.2) William Prynne, The Petition of Right of the Free-holders and Free-men (8 January, 1648).

Full titleWilliam Prynne, The Petition of Right of the Free-holders and Free-men of the Kingdom of England: Humbly presented to the Lords and Commons (their Representatives and Substitutes) from whom they expect a speedy and satisfactory answer, as their undoubted Liberty and Birth-right.

Printed in the year, 1648.

8 January, 1648.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 583; Thomason E. 422. (9.).

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

THE PETITION OF RIGHT OF THE Free-holders and Free-men OF THE Kingdom of England

In all humbleness shew unto the Lords and Commons now in Parliament assembled;

THat where as the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons in Parliament assembled, in the third year of his Majesties reign, that now is, did, in their most famous Petition of Right, among other things, claim these ensuing, as their and our undubitable Rights and Liberties, according to the Laws and Statutes of this Realm, viz.

That no Free-man in England should be compelled to contribute to make or yeeld any Gift, Loan or Benevolence, Tax, Tallage, or other such like charge, without common consent by Act of Parliament. That no Free-man may be taken or imprisoned, or disseised of his Free-hold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be out-lawed or exiled, or in any manner destroyed, or be adjudged to death, but by the Lawful Judgment of his Peers by the Law of the Land, and due process of Law.

That the quartering of Soldiers and Mariners in any Freemens houses against their wils, and compelling them to receive them, is against the Laws and Customs of this Realm, and a great grievance and vexation of the people; [Notwithstanding the Commons in this present Parliament, in their Remonstrance of the State of the Kingdom, 15 Decemb. 1641. published to all the Kingdom: That the charging of the Kingdom with billeted Soldiers (complained of in the Petition of Right, as aforesaid) and the Concommitant Design of German Horse, that the Land might either submit with fear, or be inforced with rigor to such ARBITRARY CONTRIBUTIONS, as should be required of them; was a product and effect of the Jesuited Councels, of Iesuites, Papists, Prelates, Courtiers and Counsellors, for private ends. And therefore not to be approved or endured in themselves, or in any Officers or Soldiers under their command, raised purposely to defend, and not invade our just Rights and Properties, especially since the Wars determination in this Realm, since they desire in that Remonstrance, That all Sheriffs, Iustices, and other Officers be sworn to the due execution of the Petition of Right, and those Laws which concern the Subject in his Liberty.] And that all Commissioners for the executing and putting of men to death by Martial Law, (except only in Armies in time of War) are wholy and directly contrary to the Laws and Statutes of this Realm. And did in their said Petition grievously complain, That by means of divers Commissions directed to sundry Commissioners in several Counties, his Majesties people have been, in divers places, assembled and required to lend certain sums of Money to his Majesty (pretended for the publick safety) and many of them, upon their refusal so to do, have had an Oath tendred to them, not warrantable by the Laws and Statutes of this Realm, and been constrained to become bound to make appearance and give attendance before the Privy Councel and in other places, and other of them have been therefore imprisoned, censured and sundry other ways molested and disquieted, and divers other Charges have been layd and levyed on the people in several Counties by Lord Lieutenants, Deputy Lieutenants, Commissioners for Ministers, Justices of Peace, and others against the Laws and free Customs of this Realm. And that divers Subjects have of late been imprisoned without any cause, or any just or lawful cause shewn; and when for their deliverance they were brought before his Majesties Justices by Writs of Habeas Corpora, there to undergo and receive as the Court should order, and their Keepers commanded to certifie the causes of their detainer, no cause was certified, but that they were detained by his Majesties special command, signified by the Lords of his Privy Councel, and yet were returned back to several prisons without being charged with any thing, to which they might make answer according to the Law. And that of late great companies of Soldiers and Mariners have been dispersed into divers Counties of the Realm, and the inhabitants, against their wils, have been compelled to receive them into their houses, and there to suffer them to sojourn against the Laws and Customs of this Realm to the great grievance and vexation of the people. And that divers Commissions under the great Seal had been granted to proceed according to Martial Law against Soldiers, Mariners and others, by colour and pretext whereof some of his Maiesties Subiects had been illegally put to death and executed. And also sundry grievous offendors, by colour thereof, claiming an exemption have escaped the punishments due to them by the Laws and Statutes of this Realm, by reason that divers Officers and Ministers of Justice have uniustly refused or forborn to proceed against such Offendors according to the said Laws and Statutes, upon pretence that the said Offenders were punishable by Martial Law, and by Authority of such Commissions, as aforesaid.

And therefore they did then in their said Petition most humbly pray his most Excellent Maiesty, that no man hereafter be compelled to make or yeeld any Gift, Loan, Benevolence, Tax or such like charge, without common consent by Act of Parliament. And that none be called to make answer, or take such Oath, or to give attendance, or be censured, or otherwise molested or disquieted concerning the same, or the refusal thereof. And that no Free-man, in any such manner, as is before mentioned, be imprisoned or detained. And that his Maiesty would be pleased to remove the said Soldiers and Mariners, and that his people may not be so burthened in time to come. And that the foresaid Commissions for proceeding by Martial Law may be revoked, recalled and annulled. And that hereafter, no Commissions of the like nature may issue forth to any person or persons whatsoever, to be executed as aforesaid; lest by colour of them any of his Maiesties Subiects be destroyed or put to death, contrary to the Laws and Franchises of the Land. All which they then most humbly prayed of his Maiesty, as their Rights and Liberties, according to the Laws and Statutes of this Realm. And that his Majesty also would vouchsafe to declare, that all the awards, doings and proceedings to the preiudice of his people, in any of the premises, shal not be drawn hereafter into consequence or example. To all which the King then fully condescended, and gave this royal Answer in Parliament; Let Right be done as is desired.

These undoubted Rights, Franchises and Liberties, and that our Knights and Burgesses ought to enioy their ancient Priviledges and Freedom, and to be present at all binding Votes and Ordinances, we do here claim and challenge as our Birth-right and Inheritance, not only from his Maiesty, but from both the Houses of Parliament now sitting, who have in sundry printed Remonstrances, Declarations and Protestations, and in the Solemn League and Covenant, oft times promised and seriously vowed and covenanted, in the presence of Almighty God, inviolably to maintain and preserve the same, and to bring the Infringers of them to condign and exemplary punishment, and have engaged all the wel-affected Free-born people of England, by like solemn Protestations, Leagues and Covenants, to maintain and defend the same with their lives and estates: And therefore we at this present not only humbly desire but also require both the said Houses and every Member of them, even in point of Justice, Right, Duty and Conscience, not of favor or indulgence, inviolably, without the least diminution, to maintain, defend and preserve these our Hereditary Rights and Liberties, intailed on us and our posterities by so many Statutes, confirmed and ratified by such a multitude of late Declarations, Protestations, Remonstrances, Vows and Solemn Covenants, wherein they have mutually engaged us together with themselves, and for the preservation wherof against the Kings Malignant Counsellors, and Forces, and Party, (now totally subdued) have of late years put us and the whole Kingdom to such a vast expence of Treasure and Gallant English blood: and likewise pray their publick Declaration against, and exemplary Justice upon the present open professed Invaders and Infringers of them, in a more superlative degree then ever heretofore.

For not to enumerate the manifold Encroachments on, and Violations of these our undoubted Priviledges, Rights and Franchises, by Members, Committees, and all servants, of persons military and civil imployed by both Houses, during the late uncivil Wars, occasioned the inevitable Law of pure necessity, all which we desire may be buried in perpetual oblivion, we cannot but with weeping eys & bleeding hearts, complain & remonstrat to your honors: that contrary to these undoubted rights; Priviledges and Franchises; many of us who have always stood wel-affected to the Parliament, and done and suffered much for it, have partly through the power, malice and false suggestions, either of some Members of both Houses who have born a particular speen against us, but principally through the malice and oppression of divers City and Country-Committees, Governors, Officers, Souldiers and Agents imployed by Parliamentary Authority, been most injuriously and illegally imprisoned, sequestered, plundered, put out of our Offices, Benefices, Livings, Lands, Free-holds enforced to send divers sums of money without any Act or Ordinance, to take unlawful Oaths, enter into bonds to make appearance, and give attendance upon severall persons and Committees, both in the Country, London, Westminster, and other places, for divers moneths together, and have been confined, restrained, and sundry other ways oppressed, molested and disquieted, and utterly ruined; of which when we have complayned to the Houses, we can find either no Redress at all, or such slender and slow relief, as is as bad or worse then none at all. And when we have sought our Enlargement from our unjust imprisonments in a Legal way, by writs of Habeas Corpora, in the Kings Courts; our Keepers have either refused to obey them, or to certifie the causes of our detainer, or else have certified generally, that we were detained by order or command of one or both Houses, or of some Committees or Members of Parliament, whereupon we have been remanded to our respective prisons, without being charged with any particular offence, to which we might make answer according to Law; And if we seek to right ourselves against those who have thus unjustly and maliciously imprisoned, oppressed, plundered and disseised us of our Free-holds, Lands and Goods, by actions of false imprisonment, Trespass, Trover, Assise, or the like at the Common Law, which is our Birthright; These Members and their Servants, who have injured and ruined us, plead exemption from our suits, by reason of their Priviledges, so as we neither can nor dare to sue them; and Committee-men and others, when we sue them for any injuries, Trespasses or oppressions by Land or Sea, plead the Ordinances of Indempnity, to justifie their most unjust and exorbitant actions, warranted by no Law nor Ordinance whatsoever, and by colour thereof stay both our Judgments and Executions at Law, after verdicts given against them for our relief; and force us to travail from all parts of the Kingdom unto Westminster, and there to dance attendance upon Committees of Indempnity, and the like, or many weeks and moneths, til they enforce us to spend more then the dammages we justly recovered, and to release our just Actions and Executions, at the last, contrary to our just Rights and Priviledges, the express Letter of Magna Charta; We will deny, we wil deferr right and justice to no man; And to the very purport of the Ordinances of Indempnity, which never intended to exempt any Committees or other Officers, Agents, Souldiers or Sea-men imployed by the Houses from any unjust or injurious actions done out of private malice, or for private ends, or lucre, without, besides, or against all Ordinances, or from any gross abuses of their power and trust to the peoples prejudices and oppression (all which are now patronized and maintained by pretext thereof) but only to secure them from unjust vexations and suits, for what they sincerely acted for the publike good, according to their trust and duties. And which is yet more sad and dolefull, the very greatest Malignants, who have been most active against the Parliament, and for our good affections and service to it, have burnt down much of our Houses, seized upon our goods and estates, imprisoned, beaten, wounded and mained our persons, imposed heavy taxes on us, indicted us of high Treason for bearing Armes in the Parliaments defence, and enriched themselves with our spoyles and estates; by colour of the Articles of Oxford, Exeter, Winchester, and the like; exempt themselves from our Actions and Arrests, stay our Judgments and Executions after our expence, in suits and Recoveries at the Law, when we have received not one quarter of the damages we sustained by them, by verdict and tryall; and summon us from all parts of the Kingdom, to appear and wait for divers weeks before the Committe of Complaints at Westminster, to our intolerable vexation and expence, where they find more friends and favour commonly then we, and force us to release both our damages and costs of suit to our utter undoing: The very extremity both of Injustice and ungratitude, which makes Malignants to insult and triumph over us, out of whose estates we wer by divers Remonstrances and Declarations of both Houses, promised full satisfaction for all our losses and sufferings in the Parliaments cause; who are now on the contrary thus strangely protected against our just suits against them, for our sufferings by them, and are promised a general act of Indempnity and oblivion (as we hear) to secure themselves for ever against us, whom they have quite undone; which it obtained, wil break all honest mens hearts, and discourage them ever hereafter, to act or suffer any thing for the Parliament, who instead of recompencing them for their losses and sufferings, according to promise and justice in a Parliamentary way, do even against Magna Charta it self, and all Justice and Conscience, thus cut them off from all means and hopes of recompence or relief in a Legall way, and put Cavaleers into a far better and safe condition, then the faithfulest and most suffering Parliamenteers, a very ingrate and unkind requital.

Besides we cannot but with deepest grief of soul and spirit complain, that contrary to these our undoubted Rights and Priviledges, many of our faithfullest Knights and Burgesses, whom we duly chose to consult and vote for us in Parliament, have through the malice, practise and violence of divers mutinous and Rebellious Souldiers in the Army; and some of their Confederates in the House, without our privity or consents, or without any just or legal cause, for their very fidelity to their Country, for things spoken, done and voted in the Houses, maintaining the Priviledges of Parliaments and opposing the Armies late mutinous, Rebellious, Treasonable and Seditious Practises been most falsly aspersed slandered, impeached, and forced to desert the House and Kingdom too; others of them arrested and stayed by the Army, and their Officers, without any warrant or Authority: others of them suspended the House before any Charge and Proofs against them; others expelled the House, and imprisoned in an Arbitrary and Illegal manner, when most of the Members were forced thence by the Armies violence, without any just cause at all, or any witnesses legally examined face to face, and without admitting them to make their just defence as they desired: And that divers Lords and Members of the House of Peers have likewise been impeached of High Treason, sequestred that House, and committed to custody, only for residing constantly in the House, and acting in, and as an House of Parliament, (for which to impeach them of Treason, is no lesse then Treason, and so resolved in the Parliaments of 11. R. 2. & 1. H. 1. in the case of Tresilian and his Companions) when others who dis-honorably deserted the House, and retired to the mutinous Army, then in professed disobedience to, and opposition against both Houses, are not so much as questioned; and all this by meer design and confederacy, to weaken the Presbyterians and honest party in both Houses, which were far the greatest number, and enable the Independent Faction, to vote and carry what they pleased in both Houses; who by this Machivilian Policy and power of the Army (under whose Guard and power, the King, both Houses, City, Tower, Country have been in bondage for some moneths last pass) have extraordinarily advanced their designs, and done what they pleased without any publike opposition, to the endangering of all our Liberties and Estates. Nay more then this, we must of necessity Remonstrate, that the Representative body of the Kingdom, and both Houses of Parliament, by their late Seditious and Rebellious Army, have not only been divers ways menaced, affronted, disobeyed, but likewise over-awed, and enforced to retract and null divers of their just Votes, Declarations and Ordinances against their Judgments and Wills, to passe new Votes, Orders and Ordinances sent and presented to them by the Army, to grant what demands, and release what dangerous Prisoners they desired of them; to declare themselves no Parliament, and the Acts, Orders and Ordinances passed in one or both Houses, from the 26 of July, to the 6 of August meer Nullities, during the Speakers absence in the Army, by a publike Ordinance then layd aside by the major votes, and at last enforced to passe by a party of one thousand horse (a far greater force then that of the Apprentices) drawn up into Hide-Park to over-awe the Houses, because the Generall and Army had voted them no Parliament, and their proceedings null. Since which they have to their printed Treasonable Remonstrance of the 18th of August, not only protested and declared against the Members Votes and Proceedings of both Houses, both during the Speakers absence and since, but likewise thus Traiterously and Rebelliously closeup their Remonstrance with this protest and declaration to all the world, p. 23. 24. That if any of those Members Votes and proceedings during the absence of the Speakers, and the rest of the Members of both Houses, did sit or vote in thea pretended Houses then continuing at Westminster, that hereafter intrude themselves to sit in Parliament, before they have given satisfaction to theb respective Houses whereof they are concerning the ground of their said [Editor: illegible word] at Westminster, during the absence of the said Speakers, and all evidence, acquitted themselves by sufficient evidence; That they did not procure nor give their consent as unto any of those pretended Votes, Orders or Ordinances, tending to thec raising and levying of a war (as is before (falsly) declared) or for the Kings coming forthwith to London; WE CANNOT ANY LONGER SUFFER THE SAME; but shall do that right to the Speakers and Members of both Houses who were* driven away to us, & to our selves with them,d all whom the said Members have endeavoured in as hostile manner to destroy) and also to the Kingdom (which they endeavoured [Editor: illegible word] [Editor: illegible word] a new war) to take some speedy and effective course* WHEREBY TO RESTRAIN THEM FROM BEING THEIR OWN AND OURS AND THE KINGDOMS IVDGES, in these things wherein they have made themselvese parties, and by this means to make War; that both they and others who are guilty of and parties to the aforesaid treasonable and destructive practises and proceedings against THE FREEDOM of PARLIAMENT and Peace of the Kingdom, may be brought to condign punishment, (and that) at the judgment of A FREE PARLIAMENT, consisting (duly and properly) of suchf Members of both Houses respectively, who stand clear from, such apparant and treasonable breach as is before expressed: Since which, they have in their General Councel at Putney and in their printed Papers, Voted down the House of Peers and their negative Votes, prescribed the period of this present Parliament, and a new model for the beginning, ending, Members and Priviledges of all succeeding Parliaments received and answered many publick Petitions presented to them, and voted and resolved upon the question the greatest affairs of State, as if they only were the Parliament and Superior Councel both of State and War; voted the Sale of bishops. Deans and Chapters, and Forrest Lands for the payment of their (supposed) Arrears, notwithstanding the Commons Votes to the contrary after sundry large debates; voted against the Houses sending Propositions to the King; to prevent which, as they first traiterously seised up on his person and rescued him out of the custody of the Commissioners of both Houses at Holdenby, and ever since detained him in their power per force from the Parliament, so they have lately conveyed him into the Isle of Wight, and there shut him up Prisoner without the privity and contrary to the desires of both Houses. All which unparaleld insolencies and treasonable practises, we declare to be against our Rights, Freedom and Liberties, and the Rights and Priviledges of Parliament, and of our Members there who represent us, and to his Majesties honor, and safety, in whom we have all a common interest.

And we do likewise further complain and Remonstrate that the Officers and Agitators in the Army, and their confederates in the Houses, have contrary to our foresaid Rights and Liberties many ways invaded and infringed the Rights and Priviledges of the City of London the Parliaments chiefest Strength and Magazine, and Metropolis of the whole Kingdom, which extreamly suffers in and by its sufferings; and that by altering and repealing their New Militia established by Ordinances of both Houses when ful and free, without any cause assigned, against the whole Cities desire; in marching up twice against the City in an hostile manner, not only without, but against the Votes and Commands of both Houses; in dividing and exempting the Militia of Westminster and Southwark from their Jurisdiction and Command; in seising upon and throwing down their Line and Works (raised for the Cities and both Houses securities at a vast expence) in a disgraceful and despiteful manner; in marching through the City with their whole Army and Train of Artillery in triumph in wresting the Tower of London out of their power, and putting it into the Armies and Generals Custody; in removing the Cities Lieutenant of it without any reason alledged, and placing in a New one of the Armies choyce; in committing the Lord Mayor, Recorder, Aldermen, and divers Colonel, Captains and Common Councel men and other Citizens of London (who have shewed themselves most active and cordial for the Parliament and impeaching them of such grand Misdemeanors and Treasons, which all the City and Kingdom, and their accusers own consequences inform them they were more guilty of, without ever bringing them to a legal Tryal; only for doing their duties in obeying the Parliament in their just Commands, and standing up for their just defence according to their duty and Covenant, of purpose to bring in others of their own Faction into their places to inslave the City; and commanding two Regiments of Foot to come and quarter in the City, and levy some pretended arrears to [Editor: illegible word] by open force, which many by reason of poverty for want of trade and former loans and taxes to the Parliament, are utterly unable to satisfie. And when such affronts and violence is offered to London it self by the Army, by whose contributions and loans they were first granted and have been since maintained, and that under the Parliaments Noses, who are most engaged to them for their supplies and prefer action and constant affections since their first sitting to this present; the Free-holders and Free-subiects in the Country and more remote Counties, must necessarily expect Free-quarter, affronts, pressures and violations of our just Rights and Liberties from them: The rather, because the Garrison Soldiers of the City of Bristol, who not long since refused to receive the Governor appointed them by both Houses of Parliament, have lately seised upon one of the wel affected Aldermen of that City as he was sitting on the Bench with his companions, and carried him away per force, refusing to enlarge, or admit any person to see or speak with him, or bring any provisions to him, til they receive some, moneths Arrears in ready money and good security for al their remaining pay, and an act of Indempnity for this their insolency and injurious action in particular, and all other offences in general, from both Houses. Of which unparaleld oppression and injustice from Soldiers, who pretend themselves the only Saints and Profectors of our Rights and Liberties, we cannot but be deeply sensible, and crave your speedy redress in our Liberties, Rights and Properties.

But that which most neerly concerns us, and which we can no longer endure, is this wherin we expect your present redress; That this degenerated, disobedient and mutinous Army, contrary to the Votes and Ordinances for their disbanding and securing their Arrears in March and May last past, have traiterously and rebelliously refused to disband, and kept themselves together in a body ever since, offering such affronts and violence to the Kings own royal person, both Houses of Parliament and their Members and the City of London, as no age can paralel; and yet have forced the Houses when they had impeached and driven away most of their Members, and marched up in a body against them and the City in a menacing, manner, not only to own them for their Army, but to pass a new Establishment of sixty thousand pounds a moneth for their future pay, to be levyed on the Kingdom (who now expect ease from all such Taxes) besides the Excise and all other publick payments; which now they importune the Houses may be augmented to one hundred thousand pounds each moneth, and that they themselves may have the levying thereof: which insupportable Tax being procured by force and menaces, when the Houses were neither full nor free, against former Votes and Ordinances for the Kingdoms ease, and not consented to by most of our Knights and Burgesses then driven away by the Army, and dissenting thereto when present, and being only to maintain a mutinous and seditious Army of Sectaries, Antitrinitarians, Antiscripturists, Seekers, Expectants, Anabaptists, recruited Cavaliers, and seditious, mutinous Agitators, who have offered such insufferable violence and Indignities both to the King, (whose person and life was indangered among them, as he and they confess) the Parliament, City, Country; and so earnestly endeavored to subvert all Magistracy, Monarchy, Ministry, all civil, Ecclesiastical and Military Government, Parliaments, Religion, and our ancient Laws and Liberties (as their late printed Papers evidence) that they cannot without apparant danger to the Parliament, King and Kingdom, be any longer continued together, being now so head-strong that their own Officers cannot rule, but complain publickly against them: And therefore we can neither in point of duty, conscience, law or prudence, subject to pay the said monethly Tax so unduly procured by their violence, were we able to do it, being contrary to our Solemn League and Covenant, for the maintenance of such a mutinous and rebellious Army, who endeavor to enslave and destroy both King, Parliament, City, Kingdom, and monopolize all their power, wealth and treasure into their own Trayterous hands, which they have wel-nigh effected, having gotten the Kings person, the Tower of London, all Garisons and Forces in the Kingdom by Land, and the command of the Navy by Sea; into their power, and put the City and both Houses under the Wardship of their armed guards, attending at their doors and quartering round about them, and forced the run-a-way Speakers and Members not only to enter into and subscribe the solemn Engagement to live and dye with them in this cause, but likewise to give them a ful moneths pay, by way of gratuity, for guarding them back to the Houses, where they might and ought to have continued without any danger, as the other faithful Members did, and to which they might safely have returned without the strength of the whole Army to guard them. And to add to our pressures and afflictions, this godly religious Army of disobedient Saints, who pretend only our Liberty and Freedom from Tyranny, Taxes and Oppression, demand not only this new heavy monethly Tax, and the remainder of Bishops, and all Deans and Chapters and Forrest Lands in the Kingdom, and Corporation stocks for their Arrears (which if cast up only during the time of their actual service til the time they were voted and ordered to disband, wil prove very smal or little, their free-quarter, exactions and receipts for the Parliament and Country being discompted) but (which is our sorest pressure) do violently enter into our Houses against our wils, and there lie in great multitudes many weeks and moneths together, til they quite ruine and eat out both us, our families, stocks and cattel, with their intolerable Free quarter, and that in these times of extraordinary dearth and scarcity; for which they raise and receive of us of late twice or thrice as much as their whole pay amounts unto, devouring, like so many Locusts and Caterpillars, all our grass, hay, corn, bread, beer, fewel and provisions of all sorts, without giving us one farthing recompence, and leaving us, our wives, children, families, cattel, to starve and famish; the very charge of their free-quarter (besides their insufferable insolencies and abuses of all sorts) amounting in many places to above six times, or in most places to double or treble our annual Revenues. Besides the abuses in their quartering are insufferable; Many of them take and receive money for their quarters double or treble, their pay from two or three persons at once, and yet take Oats and other provisions from them besides, or free-quarter upon others: Some of them demand and receive free-quarter in money and provisions the double or treble the number of their Troops and Companies: Others take free-quarter for their wives, truls, boys, and those who were never listed: Others of them wil be contented with none but extraordinary diet wine, strong beer, above their abilities with whom they quarter, thereby to extort money from them; and if any complain of these abuses, he is sure to be relieved with an addition of more, and more unruly quarterers then he had before. If they march from their quarters to any randezvouz, or to guard the Houses, they must have victuals and money too, til their return. Divers of the Troopers and Dragooners must have quarter for two or three horses a peece, which must have at least a peck of corn or more every day (though they lye still) both Winter and Summer; their 7200 Horse, and 1000 Dragoons devouring above two thousand bushels of corn (besides grass, hay and straw) every day of the week, and this time of dearth, when the poorer sort are ready to starve for want of bread. In brief, the abuses of free quarter are innumerable, and the burthen of it intollerable, amounting to three times more then the whole Armies pay, who are doubly payd all their pretended Arrears, in the money & provisions they have received only for free quarter upon a just account; and therfore have litle cause to be so clamorous for their pretended Arrears from the State, who have received double their Arrears of us, and yet pay us not one farthing for all our Arrears for quarters when they receive their pay. Which free quartering we do now unanimously protest against, as an high Infringement of our Hereditary Rights, Liberties, Properties and Freedom, and contrary to Magna Charta, the Petition of Right, and warranted by no express Ordinance of Parliament, now the Wars are ended, and the Army long since voted to disband, and such an excessive oppression and undoing heart-breaking vexation to us, that we neither can, nor are any longer able to undergo it.

And therefore we humbly pray and desire this of both Houses of Parliament, as our unquestionable Liberty and Birthright, of which they cannot in justice deprive us, without the highest treachery, tyranny, perjury and injustice; that all these forementioned Grievances and unsupportable Pressures, under which we now groan and languish, may be speedily and effectually redressed without the least delay, to prevent a generall Insurrection of oppressed and discontented people, whose patience, if any longer abused, we fear, will break out into unappeasable fury; and by their publike votes and Remonstrances, to declare and order for our general satisfaction and ease.

That no Habeas Corpus shall be denyed to any free Subject, imprisoned by any Committe whatsoever, or by any Officers or Agents of Parliament: and that any such person shal be bayled and discharged by the Keepers of the Great Seal in vocation time, of the Judges in the Term, upon an Habeas Corpus if no legal cause of commitment or continuance under restraint shal be returned.

That every person who hath been wel-affected to the Parliament, may have free liberty to prosecute his just remedy at Law against every Member of Parliament, Committee-man, Officer or Agent imployed by the Parliament, who hath maliciously or injuriously imprisoned, beaten, sequestred, plundred or taken away his money or goods, or entered into his bounds and possessions contrary to Law, and the Ordinances of Parliament, and the power and trust committed to him, notwithstanding any priviledg, or the Ordinances, or any Orders made for their Indempnity; which we humbly conceive, were only made to free those who acted for the Parliament from unjust suits and vexations, for acting according to their duties, and not exempt any from legal prosecutions for apparent unjust, malicious and oppressive actions and abuses of their trust and power.

That no wel affected person may be debarred from his just and legal actions against Malignants in Commission, or Arms against the Parliament, who have imprisoned, plundered and abused them for their adhering to the Parliament, by colour or pretext of any Articles Surrender, made by the General or any other, or by any future Act of Oblivion, so as they prosecute their Actions within the space of 3 years next ensuing; and that the Committee of Complaint may be inhibited to stay any such proceedings, such Judgments or Executions, as prejudicial to the Parliament, and injurious to their suffering friends.

That all Members of either House of Parliament lately suspended, imprisoned, impeached or ejected by the Armys menaces and violence, without legall tryall may be forthwith enlarged, restored and vindicated, and both Houses and their Members righted and repayred against all such who have violated their Priviledges and Freedom, and freed from the guards and power of the Army.