Conference Readings: The Levellers and the Origins of Anglo-American Constitutionalism

“The Levellers and the Origins of Anglo-American Constitutionalism”

[Revised: 28 Oct., 2016]

Table of Contents

Key

T.78 [1646.10.12] (3.18) Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646).

Tract number; sorting ID number based on date of publication or acquisition by Thomason; volume number and location in 1st edition; author; abbreviated title; approximate date of publication according to Thomason.

Session I: Personal Sovereignty and Individualism

- T.78 (8.32) Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646).

- T.70 (3.11) [Richard Overton], A Remonstrance of Many Thousand Citizens, and other Free-born People of England, To their owne House of Commons (17 July 1646).

-

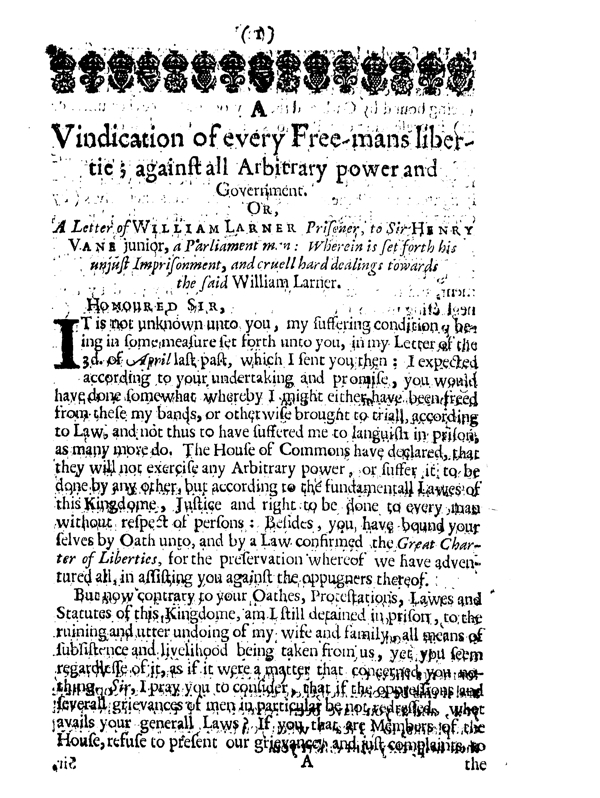

T.69 (3.10) William Larner, A Vindication of every Free-mans libertie against all Arbitrary power and Government (June 1646).

Session II: Toleration and Liberty

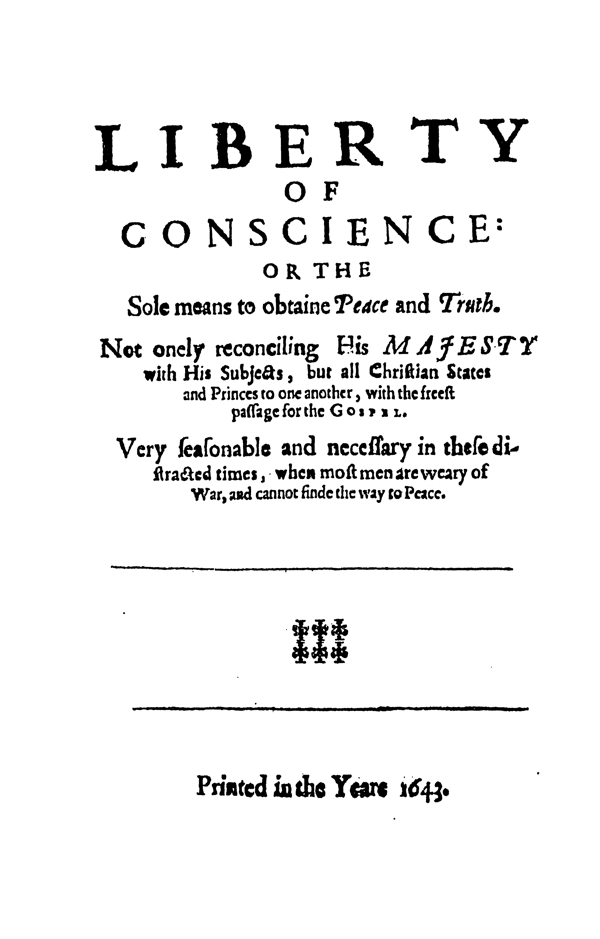

- T.35 (2.3) Henry Robinson, Liberty of Conscience: Or the Sole means to obtaine Peace and Truth (24 March 1644).

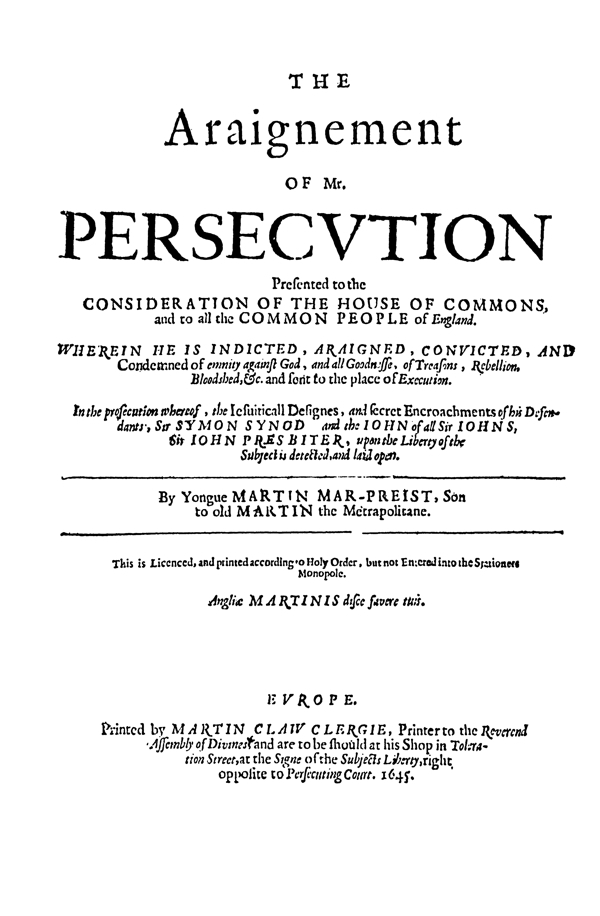

- T.44 (2.9) [Richard Overton], The Araignment of Mr. Persecution (8 April 1645)..

-

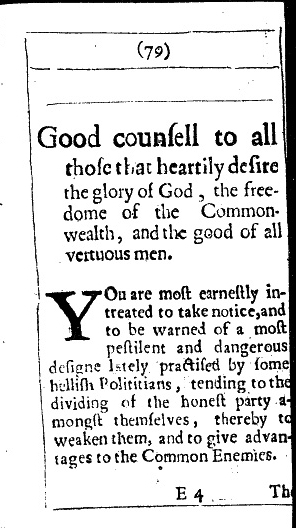

T.38 (2.5) [William Walwyn], Good Counsell to All those that heartily desire the glory of God, the freedome of the Commonwealth, and the good of all vertuous men (29 July 1644).

Session III: Legitimacy and Resistance

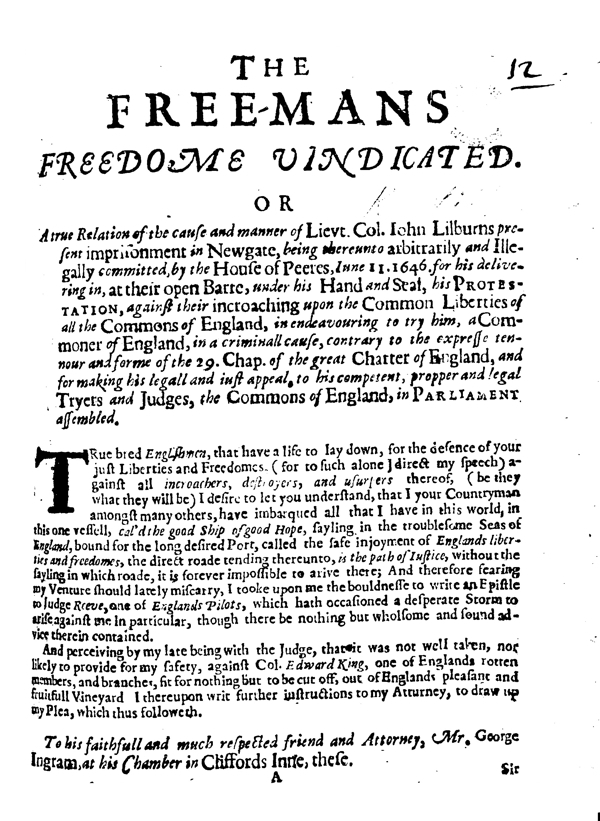

- T.66 (3.7) John Lilburne, The Free-mans Freedom Vindicated (16 June 1646).

-

T.111 (4.16) [Several Hands], [The Putney Debates], The General Council of Officers at Putney (October/November 1647).

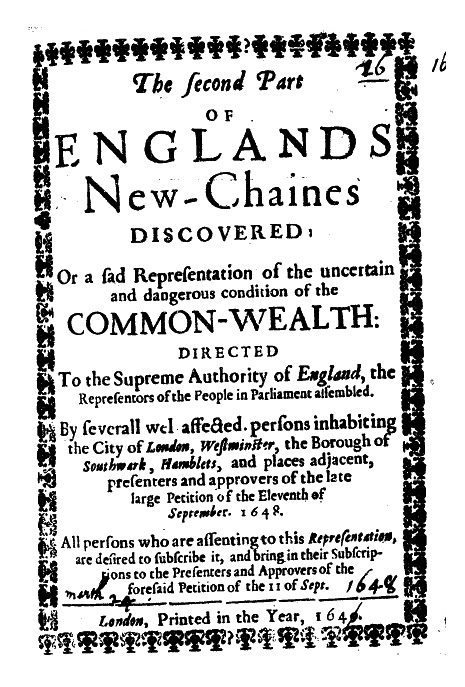

Session IV: Constitutional Programs

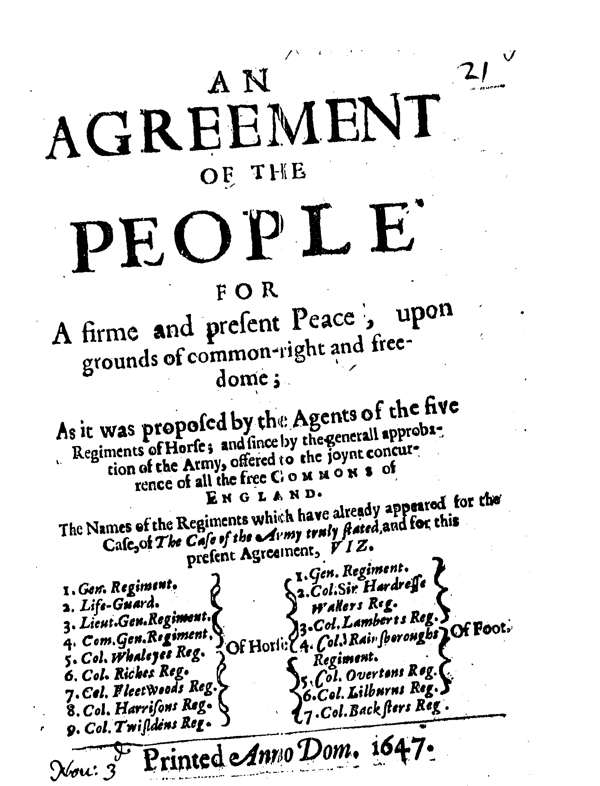

- T.115 (4.14) [Several Hands], An Agreement of the People for a firme and present Peace, upon grounds of common-right and freedome (3 November 1647)

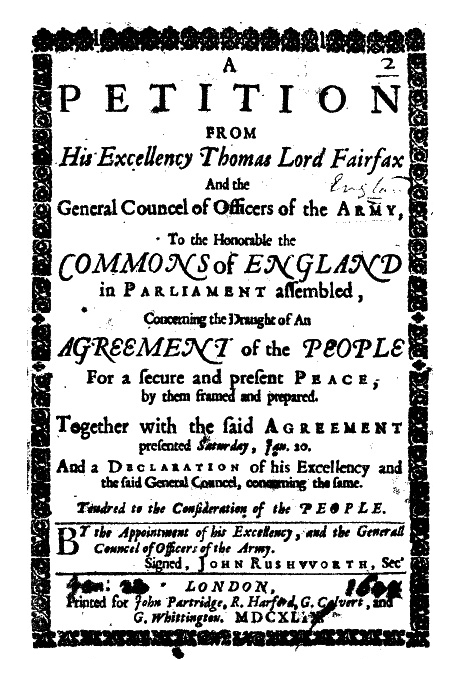

- T.179 (6.2) John Rushworth, A Petition concerning the Draught of an Agreement of the People (20 January 1649).

-

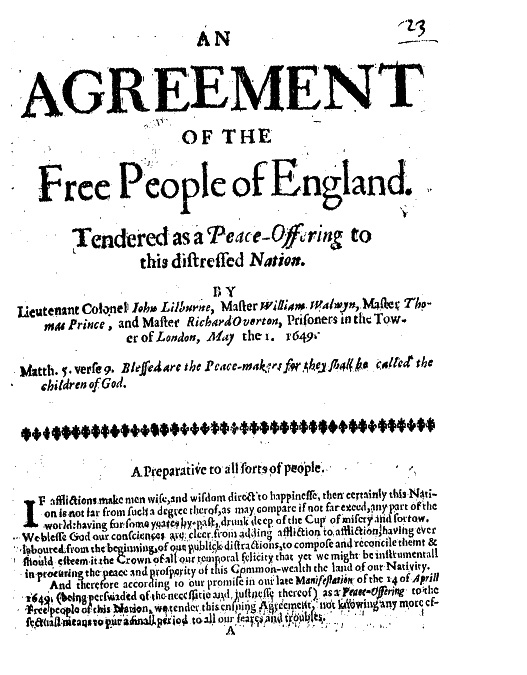

T.191 (6.11) John Lilburne, William Walwyn, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton, An Agreement of the Free People of England (1 May 1649).

Session V: Social Relations and Economic Thinking

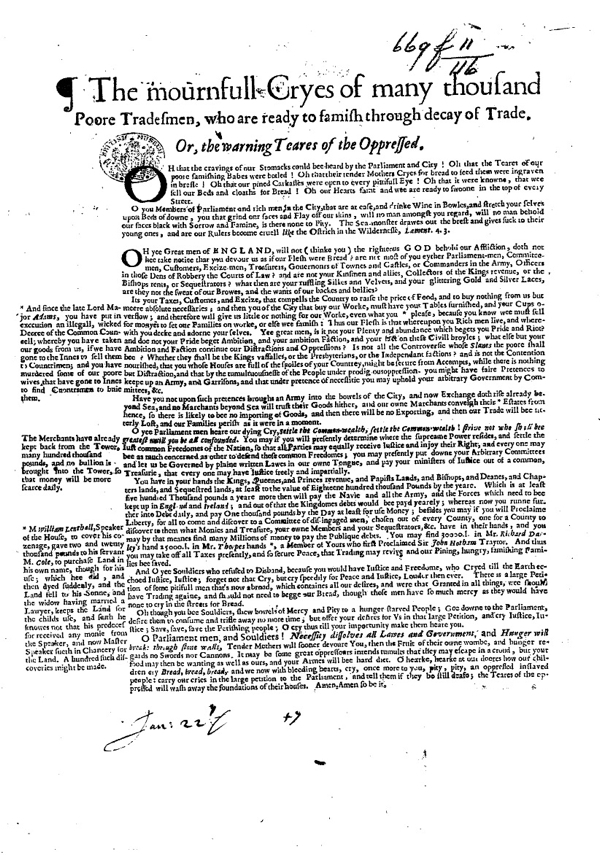

- T.130 (9.21) Anon., The Mournfull Cryes of many thousand Poore Tradesmen (22 January, 1848).

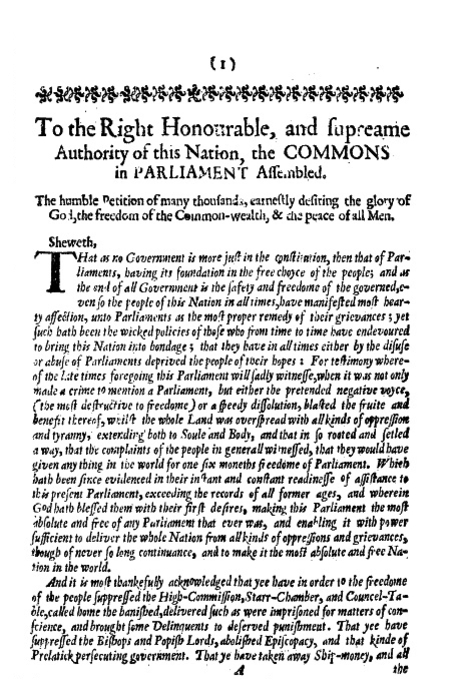

- T.150 (5.15) Anon., The Petition of 11 September, 1648 (11 Septyember, 1648)

- T.233 (7.15) William Walwyn, Walwyns Conceptions; for a Free Trade (May 1652).

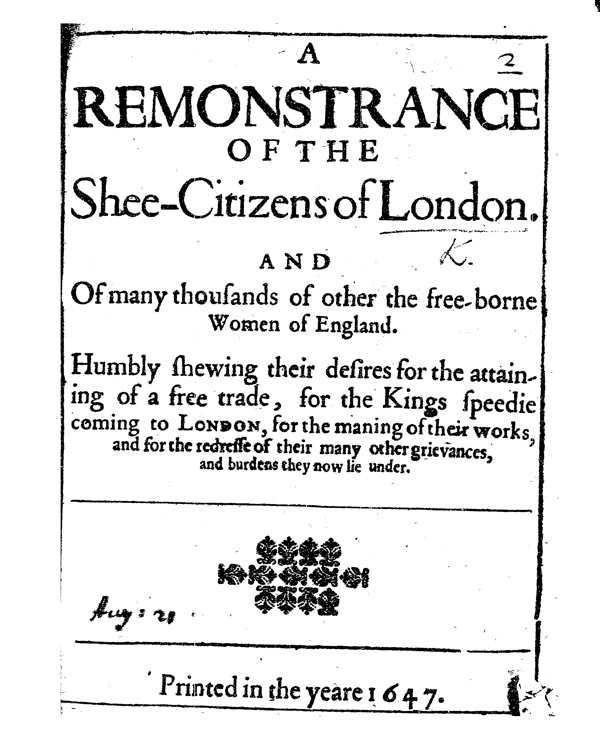

- T.108 (9.11) Anon., A Remonstrance of the Shee-Citizens of London (21 August, 1647).

Session VI: The Nature of Citizenship and Resistance

The Readings

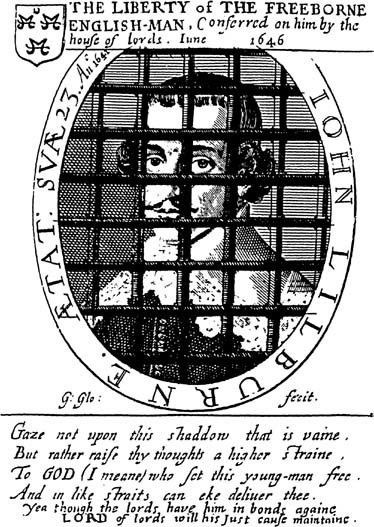

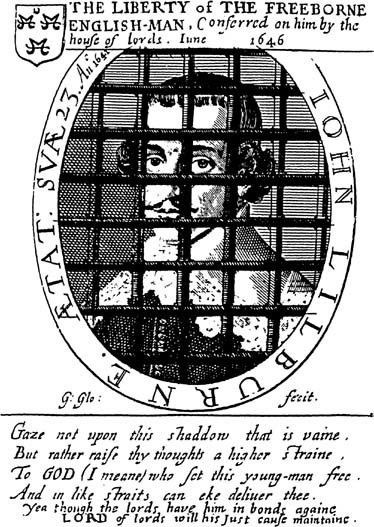

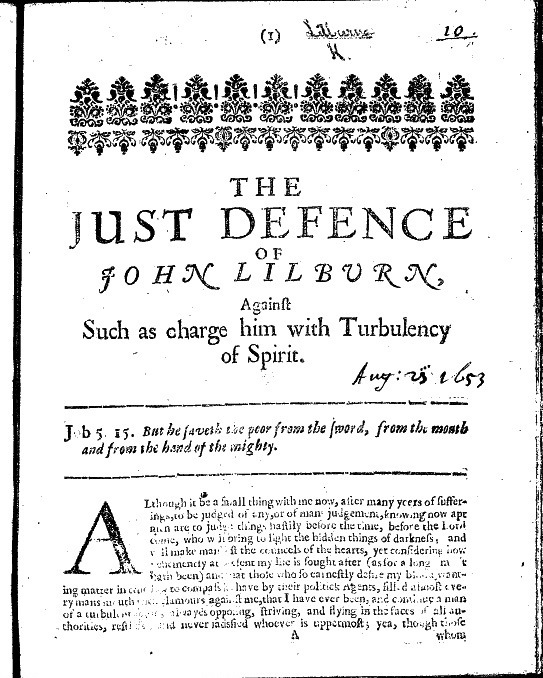

“The Liberty of the Freeborne English-Man, Conferred on him by the house of lords. June 1646."

The medallion is surrounded by the words "John lilburne. At the age of 23. The Year 1641." Made by G. Glo.

Beneath is a poem which states:

Gaze not upon this shaddow that is vaine, But rather raise thy thoughts a higher straine, To GOD (I meane) who set this young man free, And in like straits, can eke (also) deliver thee. Yea though the lords have him in bonds againe LORD of lords will his just cause maintaine.

T.78 (8.32) Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October, 1646)↩

Bibliographical Information

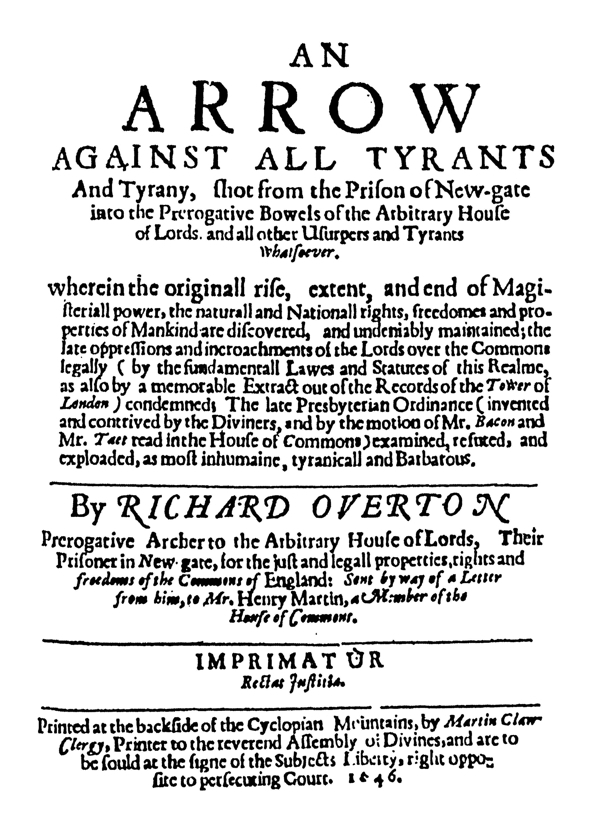

ID NumberT.78 [1646.10.12] (3.18 and 8.32) Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646).

Full titleRichard Overton, AN ARROW AGAINST ALL TYRANTS And Tyrany, shot from the

Prison of New-gate into the Prerogative Bowels of the Arbitrary House of

Lords and all other Usurpers and Tyrants Whatsoever. Wherein the originall

rise, extent, and end of Magisteriall power, the naturall and Nationall rights,

freedomes and properties of Mankind are discovered, and undeniably maintained;

the late oppressions and incroachments of the Lords over the Commons legally

(by the fundamentall Lawes and Statutes of this Realme, as also by a memorable

Extract out of the Records of the Tower of London) condemned; The late Presbyterian

Ordinance (invented and contrived by the Diviners, and by the motion of Mr.

Bacon and Mr. Taet read in the House of Commons) examined, refuted, and exploaded,

as most inhumaine, tyranicall and Barbarous. By RICHARD OVERTON Prerogative

Archer to the Arbitrary House of Lords, Their Prisoner in New gate, for the

just and legall properties, rights and freedoms of the Commons of England:

Sent by way of a Letter from him, to Mr. Henry Martin, a Member of the House

of Commons. IMPRIMATUR Rectat Justitia.

Printed at the backside of the Cyclopian Mountains, by Martin Claw-Clergy,

Printer to the reverend Assembly of Divines, and are to be sould at the signe

of the Subjects Liberty, right opposite to persecuting Court. 1646.

The pamphlet contains the following parts:

- An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny

- To the high and mighty states, the knights, citizens and burgesses in parliament assembled (England’s legal sovereign power). The humble appeal and supplication of Richard Overton

- Postscript

12 October, 1646.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 469; Thomason E. 356. (14.)

Leveller Tract: T.78 (8.32) Richard Overton, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (12 October 1646)

AN ARROVV AGAINST ALL TYRANTS And Tyrany, shot from the prison of New-gate into the Prerogative bowels of the Arbitrary House of Lords, and all other Usurpers and Tyrants whatsoever.

Sir,

TO every Individuall in nature, is given an individuall property by nature, not to be invaded or usurped by any: for every one as he is himselfe, so he hath a selfe propriety, else could he not be himselfe, and on this no second may presume to deprive any of, without manifest violation and affront to the very principles of nature, and of the Rules of equity and justice between man and man; mine and thine cannot be, except this be: No man hath power over my rights and liberties, and I over no mans; I may be but an Individuall, enjoy my selfe and my selfe propriety, and may write my selfe no more then my selfe, or presume any further; if I doe, I am an encroacher & an invader upon an other mans Right, to which I have no Right. For by naturall birth, all men are equally and alike borne to like propriety, liberty and freedome, and as we are delivered of God by the hand of nature into this world, every one with a naturall, innate freedome and propriety (as it were writ in the table of every mans heart, never to be obliterated) even so are we to live, every one equally and alike to enjoy his Birth-right and priviledge; even all whereof God by nature hath made him free.

And this by nature every one desires aimes at, and requires, for no man naturally would be befooled of his liberty by his neighbours craft, or inslaved by his neighbours might, for it is natures instinct to preserve it selfe, from all things hurtfull and obnoctious, and this in nature is granted of all to be most reasonable, equall and just; not to be rooted out of the kind, even of equall duration with the creature: And from this fountain or root, all just humain powers take their original; not immediately from God (as Kings usually plead their prerogative) but mediatly by the hand of nature, as from the represented to the representors; for originally; God hath implanted them in the creature, and from the creature those powers immediately proceed; and no further: and no more may be communicated then stands for the better being, weale, or safety thereof: and this is mans prerogative and no further, so much and no more may be given or received thereof: even so much as is conducent to a better being, more safety and freedome, and no more; he that gives more, sins against his owne flesh; and he that takes more, is a Theife and Robber to his kind: Every man by nature being a King, Priest and Prophet in his owne naturall circuite and compasse, whereof no second may partake, but by deputation, commission, and free consent from him, whose naturall right and freedome it is.

And thus Sir, and no otherwise are you instated into your soveraign capacity, for the free people of this Nation, for their better being, discipline, government, propriety and safety, have each of them communicated so much unto you (their Chosen Ones) of their naturall rights and powers, that you might thereby become their absolute Commissioners, and lawfull Deputies, but no more; and that by contraction of those their severall Individuall Communications conser’d upon, and united in you, you alone might become their own naturall proper, soveraign power, therewith singly and only impowred for their severall weales, safeties and freedomes, and no otherwise: for as by nature, no man may abuse, beat, torment, or afflict himselfe, so by nature, no man may give that power to an other, seeing he may not doe it himselfe, for no more can be communicated from the generall then is included in the particulars, whereof the generall is compounded.

So that such so deputed, are to the Generall no otherwise, then as a Schoole-master to a particular, to this or that mans familie, for as such an ones Mastership, ordering and regulating power, is but by deputation, and that ad bene placitum, and may be removed at the parents or Head masters pleasure, upon neglect or abuse thereof, and be confer’d upon another (no parents ever giving such an absolute unlimited power to such over their children, as to doe to them as they list, and not to be retracted, controuled, or restrained in their exorbitances) Even so and no otherwise is it, with you our Deputies in respect of the Generall, it is in vaine for you to thinke you have power over us, to save us or destroy us at your pleasure, to doe with us as you list, be it for our weale, or be it for our wo, and not to be enjoyned in mercy to the one, or questioned in justice for the other, for the edge of your own arguments against the King in this kind, may be turned upon your selves, for if for the salety of the people, he might in equity be opposed by you in his tyranies oppressions & cruelties, even so may you by the same rule of right reason, be opposed by the people in generall, in the like cases of distruction and ruine by you upon them, for the safety of the people is the Soveraigne Law, to which all must become subject, and for the which all powers humaine are ordained by them, for tyrany, oppression and cruelty whatsoever, and in whomsoever, is in it selfe unnaturall, illegall, yea absolutly anti magisteriall, for it is even destructive to all humaine civill society, and therefore resistable.

Now Sir the Commons of this Nation, having impowred their Body Representative, wherof you are one, with their own absolute Soveraignty, thereby Authoritively and legally to remove from amongst them all oppressions and tyranies, oppressors and tyrants, how great soever in name, place or dignity, and to protect, safegard, and defend them from all such unnaturall monsters, vipers and pests, bred of corruption or which are intrusted amongst them & as much as in them lies, to prevent all such for the future. And to that end, you have been assisted with our lives and fortunes, most liberally and freely, with most victorious and happy successe, whereby your Armes are strengthned with our might, that now you may make us all happy within the confines of this Nation, if you please; and therfore Sir, in reason, equity and justice, we deserve no lesse at your hands, and (Sir) let it not seem strange unto you, that we are thus bold with you for our own.

For by nature we are the sons of Adam, and from him have legitimatly derived a naturall propriety, right and freedome, which only we require, and how in equity you can deny us, we cannot see; It is but the just rights and prerogative of mankind (whereunto the people of England, are heires apparent as well as other Nations) which we desire: and sure you will not deny it us, that we may be men, and live like men; if you doe it will be as little safe for your selfes and posterity, as for us and our posterity, for Sir, look what bondage, thraldome, or tyrany soever you settle upon us, you certainly, or your posterity will tast of the dregs: if by your present policy and (abused) might, you chance toward it from your selves in particular, yet your posterity doe what you can, will be liable to the hazard thereof.

And therefore Sir, we desire you help for your own sakes, as well as for our selves, chiefly for the removall of two most insufferable evils, daylie encroaching and encreasing upon us, portending and threatning inevitable destruction, and confusion of your selves, of us, and of all our posterities, namely, the encroachments and usurpations of the House of LORDS, over the Commons liberties, and freedomes, together with the barberons, inhumaine, blood-thirsty desires and endevours of the Presbyterian Clergy.

For the first, namely, the exhorbitances of the LORDS, they are to such an hight aspired that contrary to all presidents the free Comoners of England are imprisoned, fined & condemned by them (their incomputent illegall, unequall, improper judges) against the expresse letter of Magna char. chap. 29. (so often urged and used) that no free man of England shall be passed upon, tryed, or condemned, but by the lawfull judgement of his equals, or by the Law of the Land, wth as saith Sir Edw. Cooke in his exposition of Mag. chap. 28. last li. is Per pares, by his peeres, that is, by his equals. And page 46. branch 1. 2. 5. in these words;

1. That no man be taken or imprisoned, but per legem terræ, that is, by the common Law, Statute Law or custome of England: For these words, per legem terræ being towards the end of this chapter, doe referre to all the pretended matters in this chapter, and this hath the first place, because the liberty of a mans person is more precious to him then all the rest that follow, and therefore it is great reason, that he should by law be relieved therein, if he be wronged, as hereafter shall be shewed.

2. No man shall be disseised, that is, put out of seison, or dispossessed of his free-hold, that is, lands or livelyhood, or if his liberties or free customes, that is, of such franchises and freedomes, and free customes, as belong to him by his free birthright; unlesse it be by the lawfull judgement, that is verdict of his equals (that is of men of his own condition) or by the Law of the Land (that is to speak it once for all) by the due course and processes of Law.

3. No man shall be in any sorts destroyed (destruere, 1. quod prius structum & sactum suit; ponitus evertere & dimere) unlesse it be by the verdict of his equals, or according to the Law of the land.

And chapter 19. of Magna Charta, it is said secundum legem & consuetudinem Anglia, after the Law and custome of England, non Regis Anglia, not of the King of England, lest it might be thought to bind the King only, nec populi Anglia, nor of the People of England, but that the Law might tend to all, it is said, per legem terræ, by the Law of the Land. Magna chapta, 29.

Against this ancient and fundamentall Law, and in the very face thereof (saith Sir Edward Cooke) he found an Act of the Parliament made in the 11. of Hen. the 7. chap. 3. that as well justices of Peace without any finding or presentment by the verdict of 12. men, upon the bare information for the King before them, should have full power and authority, by their discretions to hear and determine all offences and contempts committed or done by any person or persons against the forme, ordinance, and effect of any Statute made and not repealed: by colour of which Act, shaking this fundamentall Law, (it is not credible) saith he what horrible oppressions and exactions (to the undoing of infinite numbers of people) were committed by Sir Richard Empson Knight, and Edmund Dudly, being Justices of the Peace through England, and upon this unjust and injurious act, (as commonly in the like cases it falleth out) a new Office was errected, and they made masters of the Kings Forfitures.

But at the Parliament holden in the 1. of Hen. 8. chap. 6. this Act of Hen. 7. is receited, made void and Repealed, and the reason thereof is yeelded, for that by force of the said Act, it was manifestly known that many sinister, crafty, and forged informations had been pursued against divers of the Kings Subjects, to their great damage and unspeakable vexation: (a thing most frequent and usuall at this day and in these times) the ill successe whereof, together with the most fearfull end of these great Oppressors should deterre others from committing the like, and should admonish Parliaments in the future, that in stead of this ordinary and precious tryall Per legem Terræ they bring not in an absolute and parciall tryall by discretion, Cooke 2. institute folio. 51.

And to this and the Judgement upon Symon de Bereford, a Commoner, in the 4. yeare of Edw. 3. is an excellent precident for these times (as is to be seen upon record in the Tower, in the second Roll of Parliament held the same yeare of the said King, and delivered into the Chancery by Henry de Edenston Clerk of the Parliament) for that the said Simon de Bereford having counselled, aided and assisted Roger de Mortimer to the murther of the Father of the said King; the King commanded the Earles and Barons in the said Parliament Assembled, to give right and lawfull judgement unto the said Symon de Bereford; But the Earles, Barons and Peers came before the Lord the King in the same Parliament, and said with one voice; that the aforesaid Simon, was not their Peer or equall, wherefore, they were not bound to judge him as a Peer of the Land: Yet notwithstanding all this, the Earles, Barons and Peers (being over swaid by the King) did award and adjudge (as judges of Parliament, by the assent of the King in the said Parliament) that the said Simon as a traitor & enemy of the Realm, should be hanged & drawn, and execution accordingly was done: But as by the said Roll appeareth, it was by full Parliament condemned and adjudged as illegall, and as a precident not to be drawn into example; the words of the said Roll are these, viz.

And it is assented and agreed by our Lord the King, and all the Grandees in full Parliament, that albeit the said Peers as judges in full Parliament took upon them in presence of our Lord the King, to make and give the said Judgement by the assent of the King, upon some of them that were not their Peers, (to wit Commoners) & by reason of the murther of the Leige Lord, and destruction of him, which was so neer of the blood royall and the Kings Father, that therefore the said Peers which now are, or the Peers which shall be for the time to come, be not bound or charged to give judgement upon others then upon their Peers, nor shall doe it; but of that for ever be discharged, and acquit, and that the aforesaid Judgement now given be not drawn into example or consequent for the time to come, by which the said Peers may be charged hereafter to Judge others then their Peers, being against the Law of the Land, if any such case happen, which God defend.

Agreeth with the Record.

William Collet.

But notwithstanding all this, our Lords in Parliament take upon them as Judges in Parliament to passe judgement and sentence (even of themselves) upon the Commoners which are not their Peeres, and that to fining, imprisonment, &c. And this doth not only content them, but they even send forth their armed men, and beset, invade, assault their houses and persons in a warlike manner, and take what plunder they please, before so much as any of their pretended, illegall warrants be shewed, as was lately upon the eleventh of August 1646. perpetrated against mee and mine, which was more then the King himselfe by his legall Prerogative ever could doe, for neither by verball commands or commissions under the Great Seale of England, he could ever give any lawfull authority to any Generall, Captaine, or person whatsoever without legall triall and conviction, forceibly to assault, rob, spoile or imprison any of the free Commoners of England: and in case any free Commoner by such his illegall Commissions, Orders or warrants before they be lawfully convicted, should be assaulted, spoiled, plundered, imprisoned, &c. in such cases his agents and ministers ought to be proceeded against, resisted, apprehended, indicted and condemned (notwithstanding such commissions) as Trespassers, Theeves, Burglarers, Felons, Murderers both by Statute and common Law, as is enacted and resolvd by Magna Charta, cap. 29. 15. Eliz. 3. stat. 1. cap. 1, 2, 3, 42. Eliz. 5. cap. 13. 28. Eliz. 1. Artic. sup. chartas, cap. 2. 4. Eliz. 3. cap. 4. 5. Eliz. 3. cap. 2. 24. Eliz. 3. cap. 1. 2. Rich. 2. cap. 7. 5. Rich. 2. cap. 5. 1. Hen. 5. cap. 6. 11. Hen. 2. cap. 1. 106. 24. Hen. 8. cap. 5. 21. Jacob. cap. 3.

And if the King himselfe have not this Arbitrary power, much lesse may his Peeres or Companions, the Lords over the free Commons of England. And therefore notwithstanding such illegall censures and warrants either of King or of Lords (no legall conviction being made) the persons invaded and assaulted by such open force of Armes may lawfully arme themselves, fortifie their Houses (which are their Castles in the judgement of the Law) against them, yea, disarme, beat, wound, represse and kill them in their just necessary defence of their own persons, houses, goods wives and families, and not be guilty of the least offence, as is expresly resolved by the Statute of 21. Edw. de male factoribus in parcis, by 24. Hen. 8. cap. 5. 12. Hen. 6. 16. 14. Hen. 6. 24. 35. Hen. 6. 12. E. 4. 6.

And therefore (Sir) as even by nature and by the Law of the Land I was bound, I denyed subjection to these Lords and their arbitrary creatures; thus by open force invading and assaulting my house person, &c. no legall conviction preceding, or warrant then showen; but and if they had brought and shewen a thousand such warrants, they had all been illegall antimagisteriall & void in this case, for they have no legal power in that kind, no more then the King, but such their actions are utterly condemned, and expresly forbidden by the Law: Why therefore should you of the Representative Body sit still, and suffer these Lords thus to devour both us and our Lawes?

Be awakned, arise and consider their oppressions and encroachments, and stop their Lord-ships in their ambitious carere, for they do not cease only here, but they soar higher & higher, & now they are become arrogators to themselves, of the natural Soveraignity the Represented have conveyed and issued to their proper Representors, even challenge to themselves the tittle of the Supreamest Court of Judecature in the Land, as was claimed by the Lord Hounsden, when I was before them, which you may see more at large in a printed letter published under my name, intitled, A Defiance &c. which challenge of his (I think I may be bold to assert) was a most illegall, Anti-parliamentary, audacious presumpsion, and might better be pleaded and challenged by the King singly, then by all those Lords in a distinction from the Commons: but it is more then may be granted to the King himselfe, for the Parliament & whole Kingdom whom it represents is truly and properly the highest Supream power of all others, yea above the King himselfe:

And therefore much more above the Lords, for they can question, Cancell, disanull and utterly revoake the Kings own Royall Charters, Writs, Commissions, Pattents, &c. Though ratified with the Great Scale, even against his personal wil, as is evident by their late abrogation of sundry, Patents, Cõmissions, writs, Charters, Lone, Shipmony &c. yea the body Representative have power to enlarge or retract the very prerogative of the King, as the Statute de prærog. Reg. and the Parliament Roll of 1. Hen. 4. num. 18, doth evidence, and therefore their power is larger and higher then the Kings, and if above the Kings, much more above the Lords, who are subordinate to the King, and if the Kings Writs, Charters &c. which intrench upon the weale of the People, may be abrogated, nul’d and made voide by the Parliament, the Representateve body of the Land, and his very prerogatives bounded, restrained & limited by them, much more may the Orders, Warrants, Commitments &c. of the Lords, with their usurped prerogatives over the commons and People of England be restrained, nul’d and made void by them, and therefore these Lord must needs be inferiour to them.

Further the Legislative power is not in the King himselfe, but only in the Kingdome and body Representative, who hath power to make or to abrogate Lawes, Statutes &c. even without the Kings consent, for by law he hath not a negative voyce either in making or reversing, but by his own Coronation Oath, he is sworne, to grant fulfill and defend all rightfull Lawes, which the COMMONS of the Realme shall chuse, and to strengthen and maintain them after his power; by wch clause of the oath, is evident, that the Cõmons not the King or Lords) have power to chuse what Lawes themselves shall judge meetest, and thereto of necessity the King must assent, and this is evident by most of our former Kings and Parliaments, and especially by the Raignes Edw. 1. 2. 3. 4. Rich 2 Hen. 4. 5. & 6. So that it cannot be denied, but that the King is subordinate and inferiour to the whole Kingdome and body Representative: Therefore if the King, much more must the Lords vaile their Bonets to the Commons and may not be esteemed the upper House, or Supreame Court of Judicature of the Land.

So that seeing the Soveraigne power is not originally in the King, or personally terminated in him, then the King at most can be but chief Officer, or supream executioner of the Lawes, under whom all other legall executioners, their severall executions, functions and offices are subordinate; for indeed the Representers (in whom that power is inherent, and from whence it takes its originall) can only make conveyance thereof to their Representors, vicegerents or Deputies, and cannot possibly further extend it, for so they should go beyond themselves, wich is impossible, for ultra posse non est esse, there is no being beyond the power of being: That which goes beyond the substance and shaddow of a thing, cannot possibly be the thing it selfe, either substantially or vertually, for that which is beyond the Representors, is not representative, and so not the Kingdomes or peoples, either so much as in shaddow or substance,

Therefore the Soveraigne power (extending no further then from the Represented to the Representors) all this kind of Soveraynity challenged by any (whither of King Lords or others) is usurpation, illegitimate and illegall, and none of the Kingdomes or Peoples, neither are the People thereto obliged: Thus (Sir) seing the Soveraigne or legislative power is only from the Represented, to the Representors and cannot possibly legally further extend: the power of the King cannot be Legislative, but only executive, and he can communicate no more then he hath himselfe; and the Soveraigne power not being inherent in him, it cannot be conveyed by, or derived from him to any, for could he, he would have carried it away with him, when he left the Parliament: So that his meere prerogative creatures, cannot have that which their Lord and creator never had, hath, or can have; namely, the Legislative power: For it is a standing rule in nature, omne simile generat simile every like begetteth its like; and indeed they are as like him, as if they were spit out of his mouth.

For their proper station will not content them, but they must make incursions & inroads upon the Peoples rights and freedomes, and extend their prerogative pattent beyond their Masters compasse; Indeed all other Courts might as well challenge that prerogative of Soveraignity, yea better then this Court of Lords. But and if any Court or Courts in this Kingdome, should arrogate to themselves that dignity, to be the supreame Court of Judicatory of the Land, it would be judged no les then high Treason, to wit, for an inferiour subordinate power to advance and exalt it selfe above the power of the Parliament.

And (Sir) the oppressions, usurpations, and miseries, from this prerogative Head, are not the sole cause of our grievance and complaint, but in especiall, the most unnaturall, tyranicall, blood-thirsty desires and continuall endeavours of the Clergy, against the contrary minded in matters of conscience, wch have been so vailed, guilded and covered over, with such various, faire and specious pretences, that by the common discernings, such woolfeish, canniball, inhumaine intents against their neighbours, kindred, friends and countrymen, as is now clearely discovered, was little suspected (and lesse deserved) at their hands; but now I suppose they will scarce hereafter be so hard of beliefe, for now in plain termes, and with open face the Clergy here discover themselves in their kind, and shew plainly that inwardly they are no other but ravening wolves, even as roaring Lyons wanting their pray, going up and down, seeking whom they may devour.

For (Sir) it seems these cruell minded men to their brethren, have by the powerfull agitation of M. taet and M. Bacon, two members of the House, procured a most Romish inquisition Ordinance, to obtain an admission into the House, there to be twice read, and to be referred to a Committee, which is of such a nature, if it should be but confirmed, enacted, and established, as would draw all the innocent blood of the Saints, from righteous Abel, unto this present upon this Nation, and fill the land with more Martyrdomes, tyranies, cruelties and oppressions, then ever was in the bloody dayes of Queen Mary, yea or ever before, or since: For I may boldly say that the people of this Nation never heard of such a diabollicall, murthering, devouring Ordinance, Order, Edict or Law in their Land as is that;

So that it may be truly said unto England, we to the inhabitants thereof, for the Divell is come down unto you, (in the shape of the letter B.) having great wrath, because be knoweth he hath but a short time, for never before was the like hear’d of in England; the cruel villanous, barbarous Martyrdomes, murthers and butcherys of Gods People, under the papall and Episcopall Clergy, were not perpetated or acted by any Law, so divelish, cruell and inhumain as this, therefore what may the free People of England expect at the hands of their Presbyterian Clergy, who thus discover themselves more firce and cruell then their fellowes? Nothing but hanging, burning, branding, imprisoning, &c. is like to be the reward of the most faithfull friends to the Kingdome and Parliament, if the Clergy may be the disposers, notwithstanding their constant magnanimity, fidelity and good service both in the field and at home, for them and the State:

But sure this Ordinance was never intended to pay the Souldiers; their arears if it be, the independents are like to have the best share, let them take that for their comfort: but I believe there was more Tyth providence, then State thrift in the matter, for if the Independents, Anabaptists, and Brownists, were but sinceerly addicted to the DVE PAYMENT of TYTHES, it would be better to them in this case then, two-subsidy men, to acquit them of Fellony.

For were it not for the losse of their Trade, and spoyling their custome, an Anabaptitst, Brownist, Independent and Presbyter were all one to them, then might they without doubt have the Mercy of the Clergy, then would they not have been entered into their Spanish Inquisition Calender for absolute Fellons or need they have feared the popish soule muthering Antichristian Oath of Abjuration or branding in the left cheeke with the letter B. the new Presbyterian Mark of the Beast for you see the Devill is now againe entered amongst us in a new shape, not like an Angell of light, (as both he and his servants can transforme themselves when they please) but even in the shape of the letter B; from the power of which Presbyterian Belzebub good Lord deliver us all and let al the People say Amen; Then needed they not to have feared their Prisons, their fire and faggot, their gallowes and halters, &c. The strongest Texts in all the Presbyterian new moddle of Clergy divinity, for the maintenance & reverence of their cloth, and confutation of errours; for he that doth but so much as question that priest fatning-Ordinance for Tythes, Oblations, Obventions, &c. doth flatly deny the fundamentals of Presbytrie, for it was the first stone they laid in their building, and the second stone, the prohibition of all to teach Gods word but themselves, and so are ipso facto all Fellons. &c.

By this (Sir) you may see what bloody minded men those of the black Presbytrie be, what little love, patience, meeknes, long suffering and forbearance they have to their Brethren; neither doe they as they would be done to; or doe to others as is done to them; for they would not be so served themselves, of the Independents, neither have the Independents ever sought or desired any such thing upon them, but would beare with them in all brotherly love; if they would be but contented to live peaceably and neighbourly by them, and not thus to brand, hang, judge and condemne all for Fellons, that are not like themselves. Sure (Sir) you cannot take this murthering, bloody disposition of theirs for the Spirit of Christianity, for Christian chairety suffers long, is kind, envieth not, exalteth not it selfe, secketh not its own is not easily provoked, thinketh no evill, beareth all things, beleeveth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things; but these their desires and endevours are directly contrary.

Therefore (Sir) if you should suffer this bloody inroad of Martyrdome, cruelties and tyranies, upon the free Commoners of England, with whose weale you are betrusted, if you should be so inhumaine, undutifull, yea and unnaturall unto us, our innocent blood will be upon you, and all the blood of the righteous that shall be shed by this Ordinance, and you will be branded to future generations, for Englands bloody Parliament.

If you will not think upon us, think upon your posterities, for I cannot suppose that any one of you would have your children hang’d in case they should prove Independents, Anabaptists, Brownists; I cannot judge you so unnaturall and inhumain to your own children, therefore (Sir) if for our own sakes we shall not be protected, save us for your children sakes, (though you think your selves secure,) for ye may be assured their and our interest is interwowne in one, if wee perish, they must not think to scape. And (Sir) consider, that the cruelties, tyranics and Martyrdomes of the papall and episcopall Clergy, was one of the greatest instigations to this most unnaturall warre; and think you, if you settle a worse foundation of cruelty, that future generations will not tast of the dreags of that bitter cup?

Therefore now step in or never, and discharge your duties to God and to us, and tell us no longer, that such motions are not yet seasonable, and wee must still waite; for have we not waited on your pleasures, many faire seasons and precious occasions and opportunities these six yeares. even till the Halters are ready to be tyed to the Gallowes, and now must wee hold our peace, and waite till wee be all imprisoned, hang’d, burnt and confounded? Blame us not (Sir) if we complain against you, speak, write and plead thus with might and maine, for our lives, lawes and liberties, for they are our earthly summum bonum wherewith you are chiefly betrusted; & whereof we desire a faithful discharge at your hands in especiall, therefore be not you the men that shall betray the blood of us and our posterities, into the hands of those bloody black executioners: for God is just, and wil avenge our blood at your hands; and let Heaven and earth bear witnesse against you, that for this end, that we might be preserved and restored, wee have discharged our duties to you, both of love, fidelity and assistance, and in what else yee could demand or devise in all your severall needs, necessities and extremities, not thinking our lives, estates, nor any thing too precious to sacrifice for you and the Kingdomes safety, and shall wee now be thus unfaithfully, undutifully and ungratfully rewarded? For shame, let never such things be spoken far lesse recorded to future generations.

Thus Sir, I have so farre enboldened my selfe with you (hoping you will let greivances be uttered, that if God see it good they may be redressed, and give loosers leave to speake without offence) as I am forced to at this time, not only in the discharge of my duty to my selfe in particular, but to your selves and to our whole Country in generall for the present, and for our severall posterities for the future, and the Lord give you grace to take this timely advice, from so meane and unworthy an instrument.

One thing more (Sir) I shall be bold to crave at your hands, that you would be pleased to present my Appeale here inclosed, to your Honourable House; perchance the manner of it may beget a disaffection in you, or at least a suspition, of disfavour from the House: but howsoever, I beseech you, that you would make presentation thereof, and if any hazard and danger ensue, let it fall upon mee, for I have cast up mine accounts, I know the most that it can cost me, is but the dissolution of this fading mortality, which once must be dissolved; but after (blessed be God) commeth righteous judgement.

Thus (Sir) hoping my earnest and fervent desires after the universall freedomes and properties of this Nation in generall, and especially of the most godly and faithfull, in their consciences, persons and estates, will be a sufficient excuse with you, for this my tedious presumption upon your patience: I shal commit the premisses to your deliberate thoughts, and the issue thereof unto God; expecting and praying for his blessing upon all your faithfull and honest endevours in the prosecution thereof. And rest;

From the most contempteous

Gaole of New-gate (the

Lords benediction)

Septem. 25. 1646.

In Bonds for the just rights and

freedoms of the Commons of

England, theirs and your faithfull

friend and servant,

Richard Overton.

To the high and mighty States, the Knights Citizens and Burgesses in Parliament Assembled; (Englands legall Soveraigne power) The humble Appeale and supplication of Richard Overton, Prisoner in the most contemptible Goale of New gate.

Humbly sheweth;

THAT whereas your Petitioner under the pretence of a Criminall fact, being in a warlike manner brought before the House of Lords to be tried, and by them put to answer to Interogatories concerning himselfe, both which your Petitioner humbly conceiveth to be illegall, and contrary to the naturall rights, freedome and properties of the free Commoners of England (confirmed to thereby Magna Charta, the Petition of Right, and the Act for the abolishment of the Star-chamber) he therefore was enboldened to refuse subjection to the said House, both in the one and the other; expressing his resolution before them, that he would not infringe the private Rights and properties of himselfe, or of any one Commoner in particular, or the common Rights and properties of this Nation in generall: For which your Petitioner was by them adjudged contemptuous, & by an Order from the said House was therefore committed to the Goale of New-gate, where, from the 11. of August 1646, to this present he hath lyen, and there commanded to be kept till their Pleasures shall be further signified (as a copy of the said Order hereunto annexed doth declare) which may be perpetuall if they please, and may have their wils; for your Petitioner humbly conceiveth that thereby he is made a Prisoner to their Wils, not to the Law, except their Wils may be a Law.

Wherefore, your leige Petitioner doth make his humble appeale unto this most Soveraigne House (as to the highest Court of Judicatory in the Land, wherein all the appeales thereof are to centure, & beyond which none can legally be made) humbly craving (both in testimony of his acknowledgment of its legall regality, & of his due submission thereunto) that your Honours therein assembled, would take his cause (and in his, the cause of all the free Commoners of England, whom you represent, & for whom you sit) into your serious consideration and legall determination, that he may either by the mercy of the Law be repossessed of his just liberty and freedome, and thereby the whole Commons of England of theirs, their unjustly (as he humbly conceiveth) usurped & invaded by the House of LORDS, with due repairations of all such damages so sustained, or else that he may undergoe what penalty shall in equity by the impartiall severity of the Law he adjudged against him by this Honourable House, in case by them he shall be legally found a transgressour herein.

And Your Petitioner (as in duty

bound) shall ever pray, &c.

Die Martis 11. Augusti. 1646.

It is this day Ordered by the Lords in Parliament assembled, that [ ] Overton brought before a Committee of this House, for printing scandalous things against this House, is hereby committed to the Prison of New-gate, for his high contempt offered to this House, and to the said Committee by his contempteous words and gesture, and refusing to answer unto the Speaker: And that the said Overton shall be kept in safe custody by the Keeper of New-gate or his deputy, untill the Pleasure of the House be further signified.

To the Gentleman Usher

attending this House, or his

Deputy, to be delivered to

the Keeper of New-gate

or his Deputy.

John Brown Cleric. Parl.

Examinat. per Ra. Brisco Clrich.

de New-gate.

Postscript.

SIR,

YOur unseasonable absence from the House, chiefly while Mistres Lilborns Petition should have been read (you having a REPORT to make in her husbands behalfe, whereby the hearing thereof was defer’d and retarded) did possesse my mind with strong jealousies and feares of you, that you either preferred your own pleasure or private interest before the execution of justice and judgement, or else withdrew your selfe, on set purpose (through the strong instigation of the Lords) to evade the discharge of your trust to God and to your Country; but at your returne understanding, that you honestly & faithfully did redeem your absent time, I was dispossessed of those feares and jealousies: So that for my over-hasty censorious esteem of you, I humbly crave your excuse, hoping you will rather impute it to the fervency of my faithfull zeale to the common good, then to any malignant disposition or disaffection in me towards you: Yet (Sir) in this my suspition I was not single, for it was even become a generall surmise.

Wherefore (Sir) for the awarding your innocency for the future, from the tincture of such unjust and calumnious suspitions, be you diligent and faithfull, instant in season and out of season, omit no opportunity, (though with never so much hazard to your person, estate or family) to discharge the great trust (in you reposed with the rest of your fellow members) for the redemption of your native Country from the Arbitrary Domination and usurpations, either of the House of LORDS, or any other.

And since by the divine providence of God, it hath pleased that Honourable Assembly whereof you are a Member, to select and sever you out from amongst themselves, to be of that Committee which they have Ordained to receive the Commoners complaints against the House of LORDS, granted upon the foresaid most honourable Petition: Be you therefore impartiall, and just, active and resolute care neither for favours nor smiles, and be no respector of persons, let not the greatest Peers in the Land, be more respected with you, then somany old Bellowes-menders, Broom men, Coblers, Tinkers or Chimney-sweepers, who are all equally Free borne; with the hudgest men, and loftiest Anachuims in the Land.

Doe nothing for favour of the one, or feare of the other; and have a care of the temporary Sagacity of the new Sect of OPPORTUNITY TO POLITITIANS, whereof we have got at least two or three too many; for delayes & demurres of Justice are of more deceitfull & dangerous consequence, then the flat & open deniall of its execution, for the one keeps in suspence, makes negligent & remisse, the other provokes to speedy defence, makes active and resolute: Therefore be wise, quick, stout and impartiall: neither spare, favour, or connive at friend or foe, high or low, rich or poore, Lord or Commoner.

And let even the saying of the Lord, with which I will close this present discourse, close with your heart, and be with you to the death. Leviticus, 19. 15.

Yee shall doe no unrighteousnesse in judgement; thou shalt not respect the person of the poore, nor honour the person of the mighty, but in righteousnesse shalt thou judge thy neighbour.

October 12. 1646.

FINIS.

T.70 (3.11) [Richard Overton], A Remonstrance of Many Thousand Citizens (7 July 1646).↩

Bibliographical Information

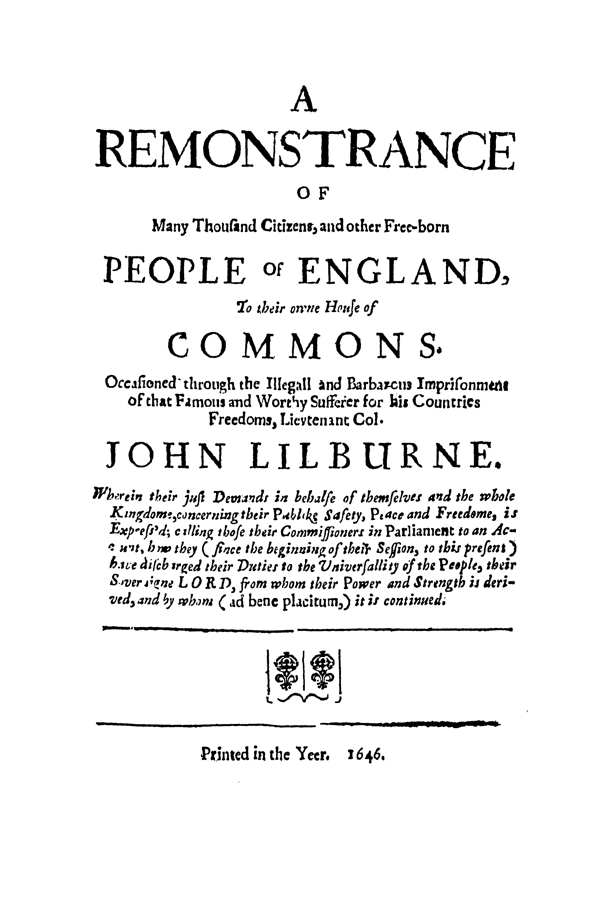

ID NumberT.70 [1646.07.17] (3.11) [Richard Overton], A Remonstrance of Many Thousand Citizens, and other Free-born People of England, To their owne House of Commons (17 July 1646).

Full title[Richard Overton], A Remonstrance of Many Thousand Citizens, and other

Free-born People of England, To their owne House of Commons. Occasioned through

the Illegall and barbarous Imprisonment of that Famous and Worthy Sufferer

for his Countries Freedoms, Lieutenant Col. John Lilburne. Wherein their

just Demands in behalfe of themselves and the whole Kingdome, concerning

their Publick Safety, Peace and Freedome, is Express’d; calling thoise their

Commissioners in Parliament to an Account, how they (since the beginning

of their Session, to this present) have discharged their Duties to the Universallity

of the People, their Sovereign Lord, from whom their Power and Strength is

derived, and by whom (ad bene placitum) it is continued.

Printed in the Yeer. 1646.

7 July 1646.

Thomason Tracts Catalog informationTT1, p. 450; E. 343. (11.)

Note: This pamphlet has an engraving of John Lilburne behind prison-bars which we have used as the title image of this collection.

Text of Pamphlet

WEE are well assured, yet cannot forget, that the cause of our choosing you to be Parliament-men, was to deliver us from all kind of Bondage, and to preserve the Common-wealth in Peace and Happinesse: For effecting whereof, we possessed you with the same Power that was in our selves, to have done the same; For wee might justly have done it our selves without you, if we had thought it convenient; choosing you [as Persons whom wee thought fitly quallified, and Faithfull, for avoiding some inconveniences.

But ye are to remember, this was only of us but a Power of trust, [which is ever revokable, and cannot be otherwise,] and to be imployed to no other end, then our owne well-being: Nor did wee choose you to continue our Trust’s longer, then the knowne established constitution of this Commonly-wealth will justly permit, and that could be but for one yeere at the most: for by our Law, a Parliament is to be called once every yeere, and oftner (if need be,) as ye well know. Wee are your Principalls, and you our Agents; it is a Truth which you cannot but acknowledge: For if you or any other shall assume, or exercise any Power, that is not derived from our Trust and choice thereunto, that Power is no lesse then usurpation and an Oppression, from which wee expect to be freed, in whomsoever we finde it; it being altogether inconsistent with the nature of just Freedome, which yee also very well understand.

The History of our Fore-fathers since they were Conquered by the Normans, doth manifest that this Nation hath been held in bondage all along ever since by the policies and force of the Officers of Trust in the Common-wealth, amongst whom, wee always esteemed Kings the chiefest: and what (in much of the formertime) was done by warre, and by impoverishing of the People, to make them slaves, and to hold them in bondage, our latter Princes have endeavoured to effect, by giving ease and wealth unto the People, but withall, corrupting their understanding, by infusing false Principles concerning Kings, and Government, and Parliaments, and Freedoms; and also using all meanes to corrupt and vitiate the manners of the youth, and strongest prop and support of the People, the Gentry.

It is wonderfull, that the failings of former Kings, to bring our Fore-fathers into bondage, together with the trouble and danger that some of them drew upon themselves and their Posterity, by those their unjust endevours, had not wrought in our latter Kings a resolution to rely on, and trust only to justice and square dealing with the People, especially considering the unaptnesse of the Nation to beare much, especially from those that pretend to love them, and unto whom they expressed so much hearty affection, (as any People in the world ever did,) as in the quiet admission of King James from Scotland, sufficient, (if any Obligation would worke Kings to Reason,) to have endeared both him and his sonne King Charles, to an inviolable love, and hearty affection to the English Nation; but it would not doe.

They choose rather to trust unto their Policies and Court Arts, to King-waste, and delusion, then to justice and plaine dealing; and did effect many things tending to our enslaving (as in your First Remonstrance; you shew skill enough to manifest the same to all the World:) and this Nation having been by their delusive Arts, and a long continued Peace, much softened and debased in judgement and Spirit, did beare far beyond its usuall temper, or any example of our Fore-Fathers, which (to our shame,) wee acknowledge.

But in conclusion, longer they would not beare, and then yee were chosen to worke our deliverance, and to Estate us in naturall and just libertie agreeable to Reason and common equitie; for whatever our Fore-fathers were; or whatever they did or suffered, or were enforced to yeeld unto; we are the men of the present age, and ought to be absolutely free from all kindes of exorbitancies, molestations or Arbitrary Power, and you wee choose to free us from all without exception or limitation, either in respect of Persons, Officers, Degrees, or things; and we were full of confidence, that ye also would have dealt impartially on our behalf, and made us the most absolute free People in the world.

But how ye have dealt with us; wee shall now let you know, and let the Righteous GOD judge between you and us; the continuall Oppressours of the Nation, have been Kings, which is so evident, that you cannot denie it; and ye yourselves have told the King, (whom yet you owne,) That his whole 16. Yeeres reigne was one continued act of the breach of the Law.

You shewed him, That you understood his under-working with Ireland, his endeavour to enforce the Parliament by the Army raised against Scotland, yee were eye-witnesses of his violent attempt about the Five Members; Yee saw evidently his purpose of raising Warre; yee have seen him engaged, and with obstinate violence, persisting in the most bloody Warre that ever this Nation knew, to the wasting and destruction of multitudes of honest and Religious People.

Yee have experience, that none but a King could doe so great intollerable mischiefes, the very name of King, proving a sufficient charme to delude many of our Brethren in Wales, Ireland, England, and Scotland too, so farre, as to fight against their own Liberties, which you know, no man under heaven could ever have done.

And yet, as if you were of Counsell with him, and were resolved to hold up his reputation, thereby to enable him to goe on in mischief, you maintaine, The King can doe no wrong, and apply all his Oppressions to Evill Counsellors, begging and intreating him in such submissive language, to returne to his Kingly Office and Parliament, as if you were resolved to make us beleeve, hee were a God, without whose presence, all must fall to ruine, or as if it were impossible for any Nation to be happy without a King.

You cannot fight for our Liberties, but it must be in the Name of King and Parliament; he that speakes of his cruelties, must be thrust out of your House and society; your Preachers must pray for him, as if he had not deserved to be excommunicated all Christian Society, or as if yee or they thought God were a respecter of the Persons of Kings in judgement.

By this and other your like dealings, your frequent treating, and tampering to maintaine his honour, Wee that have trusted you to deliver us from his Opressions, and to preserve us from his cruelties, are wasted and consumed (in multitudes) to manifold miseries, whilst you lie ready with open armes to receive him, and to make him a great and glorious King.

Have you shoke this Nation like an Earth-quake, to produce no more than this for us; Is it for this, that ye have made so free use, & been so bold both with our Persons & Estates? And doe you (because of our readings to comply with your desires in all things) conceive us so sottish, as to be contented with such unworthy returnes of our trust and Love? No; it is high time wee be plaine with you; WEE are not, nor SHALL not be so contented; Wee doe expect according to reason, that yee should in the first place, declare and set forth King Charles his wickednesse openly before the world, and withall, to shew the intollerable inconyeniences of having a Kingly Government, from the constant evill practices of those of this Nation; and so to declare King Charles an enemy, and to publish your resolution, never to have any more, but to acquite us of so great a charge and trouble forever, and to convert the great revenue of the Crowne to the publike treasure, to make good the injuries and injustices done heretofore, and of late by those that have possessed the same; and this we expected long since at your hand, and untill this be done, wee shall not thinke our selves well dealt withall in this originall of all Oppressions, to wit Kings.

Yee must also deal better with us concerning the Lords, then you have done? Yee only are chosen by Us the People; and therefore in you onely is the Power of binding the whole Nation, by making, altering, or abolishing of Lawes; Yee have therefore prejudiced Us, in acting so, as if ye could not make a Law without both the Royall assent of the King (so ye are pleased to expresse your selves,) and the assent of the Lords; yet when either King or Lords assent not to what you approve, yee have so much sense of your owne Power, as to assent what yee thinke good by an Order of your owne House.

What is this but to blinde our eyes, that Wee should not know where our Power is lodged, nor to whom to aply our selves for the use thereof; but if We want a Law, Wee must awaite till the King and Lords assent; if an Ordinance, then Wee must waite till the Lords assent; yet ye knowing their assent to be meerly formall, (as having no root in the choice of the People, from whom the Power that is just must be derived,) doe frequently importune their assent, which implies a most grosse absurditie.

For where their assent is necessary and essentiall, they must be as Free as you, to assent, or dissent as their understandings and Consciences should guide them: and might as justly importune you, as yee them. Yee ought in Conscience to reduce this case also to a certaintie, and not to waste time, and open your Counsells, and be lyable to so many Obstructions as yee have been.

But to prevaile with them (enjoying their Honours and Possessions,) to be lyable, and stand to be chosen for Knights and Burgesses by the People, as other the Gentry and Free-men of this Nation doe, which will be an Obligation upon them, as having one and the same interest: then also they would be distinguished by their vertues, and love to the Common-wealth, whereas now they Act and Vote in our affaires but as intruders, or as thrust upon us by Kings, to make good their Interests, which to this day have been to bring us into a slavish subjection to their wills.

Nor is there any reason, that they should in any measure, be lesse lyable to any Law then the Gentry are; Why should any of them assault, strike, or beate any, and not be lyable to the Law, as other men are? Why should not they be as lyable to their debts as other men? there is no reason: yet have yee stood still, and seen many of us, and some of your selves violently abused without repairation.

Wee desire you to free us from these abuses, and their negative Voices, or else tell us, that it is reasonable wee should be slaves, this being a perpetuall prejudice in our Government, neither consulting with Freedome nor Safety: with Freedome it cannot; for in this way of Voting in all Affaires of the Common-wealth, being not Chosen thereunto by the People, they are therein Masters & Lords of the People, which necessarily implyes the People to be their servants and vassalls, and they have used many of us accordingly, by committing divers to Prison upon their owne Authority, namely William Larner, Liev. Col. John Lilburne, and other worthy Sufferers, who upon Appeale unto you, have not beene relieved.

Wee must therefore pray you to make a Law against all kinds of Arbitrary Government, as the highest capitall offence against the Common-wealth, and to reduce all conditions of men to a certainty, that none hence-forward may presume or plead any thing in way of excuse, and that ye will leave no favour or scruple of Tyranicall Power over us in any whatsoever.

Time hath revealed hidden things unto us, things covered over thick and threefold with pretences of the true Reformed Religion, when as wee see apparently, that this Nation, and that of Scotland, are joyned together in a most bloody and consuming Warre, by the waste and policie of a sort of Lords in each Nation, that were male-contents, and vexed that the King had advanced others, and not themselves to the manageing of State-affaires.

Which they suffered till the King increasing his Oppressions in both Nations, gave them opportunity to reveale themselves, and then they resolve to bring the King to their bow and regulation, and to exclude all those from managing State-affaires that hee had advanced thereunto, and who were growne so insolent and presumptuous, as these discontented ones were lyable to continuall molestations from them, either by practices at Counsel-table, High-Commission, or Starre-chamber.

So as their work was to subvert the Monarchiall Lords and Clergy, and therewithall, to abate the Power of the King, and to Order him: but this was a mighty worke, and they were nowise able to effect it of themselves: therefore (say they,) the generallity of the People must be engaged; and how must this be done? Why say they, wee must associate with that part of the Clergy that are now made underlings, and others of them that have been oppressed, and with the most zealous religious Non-conformists, and by the helpe of these, wee will lay before the Generalitie of the People, all the Popish Innovations in Religion, all the Oppressions of the Bishops and High-Commission, all the exorbitances of the Counsell-board, and Star-chamber, all the injustice of the Chancery, and Courts of Justice, all the illegall Taxations, as Ship-mony, Pattents, and Projects, whereby we shall be sure to get into our Party, the generalitie of the Citie of London, and all the considerable substantiall People of both Nations.

By whose cry and importunity we shall have a Parliament, which wee shall by our manifold wayes, alliant, dependant, and relations soone worke to our purposes.

But (say some) this will never be effected without a Warre, for the King will have a strong party, and he will never submit to us; ’tis not expected otherwise (say they) and great and vaste sums of money must be raised, and Souldiers and Ammunition must be had, whereof wee shall not need to feare any want: for what will not an opprest, rich, and Religious People doe, to be delivered from all kinds of Oppression, both Spirituall and Temporall, and to be restored to purity and freedome in Religion, and to the just liberty of their Persons and Estates?

All our care must be to hold all at our Command and disposing; for if this People thus stirred up by us, should make an end too soon with the King and his party, it is much to be doubted, they would place the Supreme Power in their House of Commons, unto whom only of right it belongeth, they only being chosen by the People, which is so presently discerned, that as wee have a care the King and his Lords must not prevaile; so more especially, wee must be carefull the Supreme Power fall not into the Peoples hands, or House of Commons.

Therefore wee must so act, as not to make an end with the King and his Party, till by expence of time and treasure, a long, bloody and consuming War, decay of trade, and multitudes of the highest Impositions, the People by degrees are tyred and wearied, so as they shall not be able to contest or dispute with us, either about Supreame or inferiour Power; but wee will be able, afore they are aware, to give them both Law and Religion.

In Scotland it will be easie to establish the Presbyteriall Government in the Church, and that being once effected, it will not be much difficult in England, upon a pretence of uniformity in both Nations, and the like, unto which there will be found a Clergy as willing as wee, it giving them as absolute a Ministery over the Consciences of the People, over the Persons and Purses, as wee our selves aime at, or desire.

And if any shall presume to oppose either us or them, wee shall be easily able by the helpe of the Clergy, by our Party in the House of Commons, and by their and our influence in all parts of both Nations, easily to crush and suppress them.

Well (saies some) all this may be done, but wee, without abundance of travell to our selves, and wounding our owne Consciences, for wee must grosly dissemble before God, and all the world will see it in time; for wee can never doe all this that yee aime at, but by the very same oppressions as wee practised by the King, the Bishops, and all those his tyranicall Instruments, both in Religion, and Civill Government.

And it will never last or continue long, the People will see it, and hate you for it, more then ever they hated the former Tyrants and Oppressours: were it not better and safer for us to be just, and really to doe that for the People, which wee pretend, and for which wee shall so freely spend their lives and Estates, and so have their Love, and enjoy the Peace of quiet Consciences?

For (say they) are not Wee a LORD, a Peere of the Kingdom? Have you your Lordship or Peerage, or those Honours and Priviledges that belong thereunto from the love and Election of the People? Your interest is as different from theirs, and as inconsistent with their freedoms, as those Lords and Clergy are, whom wee strive to supplant.

And therefore, rather then satisfie the Peoples expectations in what concernes their Freedoms, it were much better to continue as wee are, and never disturbe the King in his Prerogatives, nor his Lords and Prelates in their Priviledges: and therefore let us be as one, and when wee talke of Conscience, let us make conscience, to make good unto our selves and our Posterities those Dignities, Honours and Preheminencies conveyed unto us by our Noble Progenitours, by all the meanes wee can; not making questions for Conscience sake, or any other things; and if wee be united in our endeavours, and worke wisely, observing when to advance, and when to give ground, wee cannot faile of successe, which will be an honour to our Names for ever.

These are the strong delusions that have been amongst us, and the mystery of iniquity hath wrought most vehemently in all our affaires: Hence it was that Strafford was so long in tryall, and that he had no greater heads to beare his company. Hence it was that the King was not called to an account for his oppressive Government, and that the treachery of those that would have enforced you, was not severely punished.

That the King gained time to raise an Army, and the Queene to furnish Ammunition; that our first and second Army was so ill formed, and as ill managed; Sherburn, Brainford, Exeter, the slender use of the Associate Counties, the slight garding of the sea, Oxford, Dermington, the West Defeate, did all proceed from (and upon) the Mystery of Iniquity.

The King and his Party had been nothing in your hands, had not some of you been engaged, and some of you ensnared, and the rest of you over-borne with this Mystery, which you may now easily perceive, if you have a minde thereunto, that yee were put upon the continuation of this Parliament, during the pleasure of both Houses, was from this Mystery, because in time these Politicians had hopes to worke, and pervert you to forsake the common Interest of those that choose and trusted you to promote their unjust Designe to enslave us; wherein they have prevailed too too much.

For Wee must deale plainly with you, yee have long time acted more like the House of Peers then the House of Commons: Wee can scarcely approach your Door with a Request or motion, though by way of Petition, but yee hold long debates, whether Wee break not your Priviledges; the Kings, or the Lords pretended Prerogatives never made a greater noise, nor was made more dreadfull then the Name of Priviledge of the House of Commons.

Your Members in all Impositions must not be taxed in the places where they live, like other men: Your servants have their Priviledges too. To accuse or prosecute any of you, is become dangerous to the Prosecutors. Yee have imprisonments as frequent for either Witnesses or Prosecutors, as ever the Star-chamber had, and yee are furnished with new devised Arguments, to prove, that yee onely may justly doe these grosse injustices, which the Starre-Chamber, High-Commission, and Counsell-board might not doe.

And for doing whereof (whil’st yee were untainted,) yee abolished them, for yee now frequently commit mens Persons to Prison without shewing Cause; Yee examine men upon Interogatories and Questions against themselves, and Imprison them for refusing to answere: And ye have Officious servile men, that write and publish Sophisticall Arguments to justifie your so doing, for which they are rewarded and countenanced, as the Starre-Chamber and High-Commission-beagles lately were.

Whilst those that ventured their lives for your establishment, are many of them vexed and molested, and impoverished by them; Yee have entertained to be your Committees servants, those very prowling Varlets that were imployed by those unjust Courts, who took pleasure to torment honest conscionable People; yet vex and molest honest men for matters of Religion, and difference with you and your Synod in judgement, and take upon you to determine of Doctrine and Discipline, approving this, and reproaching that, just like unto former ignorant pollitick. and superstitious Parliaments and Convocations: And thereby have divided honest People amongst themselves, by countenancing only those of the Presbitry, and discountenancing all the Separation, Anabaptists and Independents.

And though it resteth in you to acquiet all differences in affection, though not in judgement, by permitting every one to be fully perswaded in their owne mindes, commanding all Reproach to cease; yet as yee also had admitted Machiavells Maxime, Divide & impera, divide and prevaile; yee countenance onely one, open the Printing-presse onely unto one, and that to the Presbytry, and suffer them to raile and abuse, and domineere over all the rest, as if also ye had discovered and digested, That without a powerfull compulsive Presbytry in the Church, a compulsive mastership, or Arristocraticall Government over the People in the State, could never long be maintained.

Whereas truely wee are well assured, neither you, nor none else, can have any into Power at all to conclude the People in matters that concerne the Worship of God, for therein every one of us ought to be fully assured in our owne mindes, and to be sure to Worship him according to our Consciences.

Yee may propose what Forme yee conceive best, and most available for Information and well-being of the Nation, and may perswade and invite thereunto, but compell, yee cannot justly; for ye have no Power from Us so to doe, nor could you have; for we could not conferre a Power that was not in our selves, there being none of us, that can without wilfull sinne binde our selves to worship God after any other way, then what (to a tittle,) in our owne particular understandings, wee approve to be just.

And therefore We could not referre our selves to you in things of this Nature; and surely, if We could not conferre this Power upon you, yee cannot have it, and so not exercise it justly; Nay, as we ought not to revile or reproach any man for his differing with us in judgement, more then wee would be reviled or reproached for ours; even so yee ought not to countenance any Reproachers or revilers, or molesters for matters of Conscience.

But to protect and defend all that live peaceably in the Commonwealth, of what judgement or way of Worship whatsoever; and if ye would bend your mindes thereunto, and leave your selves open to give care, and to consider such things as would be presented unto you, a just way would be discovered for the Peace & quiet of the land in generall, and of every well-minded Person in particular.

But if you lock up your selves from hearing all voices; how is it possible you should try all things. It is not for you to assume a Power to controule and force Religion, or a way of Church Government, upon the People, because former Parliaments have so done; yee are first to prove that yee could have such a Power justly entrusted unto you by the People that trusted you, (which you see you have not,) we may happily be answered, that the Kings Writt that summons a Parliament, and directs the People to choose Knights and Burgesses, implyes the Establishment of Religion.

To which wee answere, that if Kings would prove themselves Lawfull Magistrates, they must prove themselves to be so, by a lawfull derivation of their Authority, which must be from the voluntary trust of the People, and then the case is the same with them, as between the People & you, they as you, being possessed of no more Power then what is in the People justly to intrust, and then all implications in the Writts, of the Establishment of Religion, sheweth that in that particular, as many other, we remain under the Norman yoke of an unlawfull Power, from which wee ought to free our selves; and which yee ought not to maintaine upon us, but to abrogate.

But ye have listned to any Counsells, rather then to the voice of us that trusted you: Why is it that you have stopt the Presse; but that you would have nothing but pleasing flattering Discourses, and go on to make your selves partakers of the Lordship over us, without hearing any thing to the contrary: yea, your Lords and Clergy long to have us in the same condition with our deluded brethren, the Commons of Scotland, where their understandings are so captivated with a Reverend opinion of their Presbytry, that they really beleeve them to be by Divine Authority, and are as zealous therein, as ever the poore deceived Papists were.

As much they live in feare of their thunder-bolts of Excommunication, and good cause they have, poor soules, for those Excommunications are so followed with the civill Sanction, or secular Power, that they are able to crush any opposer or dissenter to dust, to undoe or ruine any man: so absolute a Power hath their new Clergy already gained over the Poore People there, and earnestly labour to bring us into the same condition, because if wee should live in greater Freedome in this Nation, it would (they know,) in time be observed by their People, whose understandings would be thereby informed, and then they would grow impatient of their thraldome, and shake off their yoake.

They are also in no lesse bondage in things Civill, the Lords and great Men over-rule all, as they please; the People are scarce free in any thing.

Friends, these are known Truths.

And hence it is, that in their Counsells here, they adhere to those that maintaine their owne greatnesse, and usurped rule over us, lest if wee should here possesse greater liberty, then their vassalls the People in Scotland, they might in short time observe the same, and discharge themselves of their Oppressions.

It is from the mystery of iniquity, that yee have never made that use of the People of this Nation, in your warre, as you might have done, but have chosen rather to hazard their coming in, then to Arme your owne native undoubted friends; by which meanes they are possessed of too many considerable strengths of this Nation and speak such language in their late published papers, as if they were not payed for their slow assistance.

Whereas yee might have ended the Warre long ere this, if by Sea or Land you had shewed your selves resolved to make us a Free-People; but it is evident, a change of our bondage is the uttermost is intended us, and that too for a worse, and longer; if wee shall be so contended, but it is strange you should imagine.

But the truth is, wee finde none are so much hated by you, as those you thinke doe discerne those your purposes, or that apply themselves unto you, with motions tending to divert you from proceeding therein: for some yeers now, no condition of men can prevaile with you, to ammend any thing that is amisse in the Common-wealth.

The exorbitances in the Cities Government, and the strivings about Prerogatives in the Major and Aldermen, against the Freedoms of the Commons, (and to their extreme prejudice,) are returned to the same point they were at in Garrawayes time, which you observe, and move not, nor assist the Commons; Nay, worse then in his time, they are justified by the Major, in a book published, and sent by him to every Common-Counsell-man.

The oppression of the Turky Company, and the Adventerers Company, and all other infringements of our Native Liberties of the same nature, and which in the beginnings of the Parliament, yee seemed to abhominate, are now by you complyed withall, and licensed to goe on in their Oppressions.

Yee know, the Lawes of this Nation are unworthy a Free People, and deserve from first to last, to be considered, and seriously debated, and reduced to an agreement with common equity, and right reason, which ought to be the Forme and Life of every Government. Magna Charta it self being but a beggerly thing, containing many markes of intollerable bondage, & the Lawes that have been made since by Parliaments, have in very many particulars made our Government much more oppressive and intollerable.

The Norman way for ending of Controversies, was much more abusive then the English way, yet the Conquerour, contrary to his Oath introduced the Norman Lawes, and his litigious and vexatious way amongst us; the like he did also for punishment of malefactours, Controversies of all natures, having before a quick and finall dispatch in every hundred.

He erected a trade of judges and Lawyers, to sell justice and injustice at his owne unconscionable rate, and in what time bee pleased; the corruption whereof is yet remaining upon us, to our continuall impoverishing and molestation; from which we thought you should have delivered us.

Yee know also, Imprisonment for Debt, is not from the beginning; Yet ye thinke not of these many Thousand Persons and Families that are destroyed thereby, yee are Rich, and abound in goods, and have need of nothing; but the afflictions of the poore; your hunger-starved brethren, ye have no compassion of; Your zeal makes a noise as farre as Argiere, to deliver those captived Christians at the charge of others, but those whom your owne unjust Lawes hold captive in your owne Prisons; these are too neere you to thinke of; Nay, yee suffer poor Christians, for whom Christ died to kneel before you in the streets, aged, sick and cripled, begging your halfe-penny Charities, and yee rustle by them in your Coaches and silkes daily, without regard, or taking any course for their constant reliefe, their sight would melt the heart of any Christian, and yet it moves not you nor your Clergy.

Wee intreat you to consider what difference there is, between binding a man to an Oare, as a Gally-slave in Turkie or Argiere, and Pressing of men to serve in your Warre; to surprize a man on the sudden, force him from his Calling, where he lived comfortably, from a good trade; from his dear Parents, Wife or Children, against inclination, disposition to fight for a Cause hee understands not, and in Company of such, as he hath no comfort to be withall; for Pay, that will scarce give him sustenance; and if he live, to returne to a lost trade, or beggery, or not much better: If any Tyranny or cruelty exceed this; it must be worse then that of a Turkish Gally-slave.

But yee are apt to say, What remedy, men wee must have? To which we answer, in behalfe of ourselves, and our too much injured Brethren, that are Pressed; That the Hollanders our provident Neighbours have no such cruelties, esteeming nothing more unjust, or unreasonable, yet they want no men; and if ye would take care, that all sorts of men might find comfort and contentment in your Government, yee would not need to enforce men to serve your Warres.

And if yee would in many things follow their good example, and make this Nation a State, free from the Oppression of Kings, and the corruptions of the Court, and shew love to the People in the Constitutions of your Government, the affection of the People, would satisfie all common and publike Occasions: and in many particulars wee can shew you a remedy for this and all other inconveniences, if wee could find you inclinable to heare us.

Yee are extreamely altered in demeanour towards us, in the beginning yee seemed to know what Freedome was; made a distinction of honest men, whether rich or poor, all were welcome to you, and yee would mix your selves with us in a loving familiar way, void of Courtly observance or behaviour.

Yee kept your Committee doores open, all might heare & judge of your dealings, hardly ye would permit men to stand bareheaded before you, some of you telling them, ye more regarded their health, and that they should not deem of you, as of other domineering Courts, yee and they were one, all Commons of England; and the like ingenious carriage, by which ye wanne our affections to that height, that ye no sooner demanded any thing but it was effected; yee did well then, who did hinder you? the mystery of iniquity, that was it that perverted your course.