1791: US Bill of Rights (1st 10 Amendments) - with commentary

- Collections: Law

- Collections: The American Revolution and Constitution

Source: James McClellan's Liberty, Order, and Justice: An Introduction to the Constitutional Principles of American Government (3rd ed.) (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000).

C. The Bill Of Rights

The first ten amendments were proposed by Congress in 1789, at their first session; and, having received the ratification of the legislatures of three-fourths of the several States, they became a part of the Constitution December 15, 1791, and are known as the Bill of Rights.

[Amendment I.]

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

[Amendment II.]

A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

[Amendment III.]

No Soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

[Amendment IV.]

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

[Amendment V.]

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject, for the same offense, to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled, in any criminal case, to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

[Amendment VI.]

In all criminal prosecutions the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

[Amendment VII.]

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

[Amendment VIII.]

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

[Amendment IX.]

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

[Amendment X.]

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively or to the people.

* * * * *

Some of the State constitutions drawn up during the Revolution included bills of rights. The most famous and influential of these was Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason in 1776. (Mason also had a large hand in writing the Virginian Constitution at about the same time. Strictly speaking, the Declaration of Rights was not part of that constitution.) It is upon Mason’s Declaration of Rights that much of the Bill of Rights of the Constitution is founded. The principal author of the Bill of Rights, however, was James Madison.

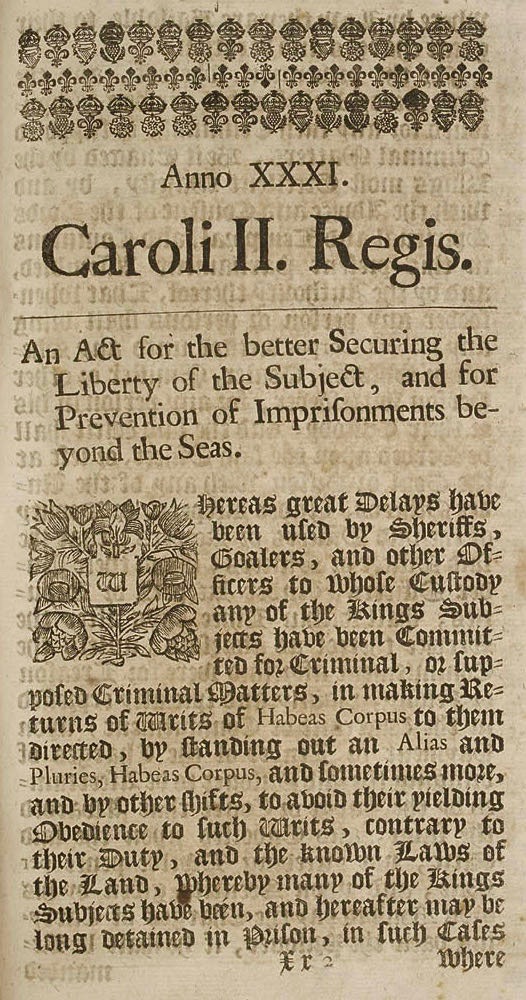

All early Americans with any serious interest in politics knew something about the English Bill (or Declaration) of Rights of 1688. But, as in many other matters, American leaders tended to be influenced more by recent or colonial American precedents and example than by those from British history. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both earnestly supported the idea of a national bill of rights, and so did many other leading men.

We shall now examine those ten amendments, one by one, with a view to grasping their original purpose or meaning. For people of our time, the phrases of those amendments, like the phrases of the original Seven Articles of the Constitution, sometimes require interpretation. What did those words mean, as people used them near the end of the eighteenth century? One way to find out is to consult the first great dictionary of the English language, Samuel Johnson’s, published at London in 1775; or, later, Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language (1828). It is important to understand precisely, so far as possible, the meanings intended by the men (chiefly James Madison and George Mason) whose phrases are found in the Bill of Rights, because many important cases of constitutional law that affect millions of Americans are today decided on the presumed significance of certain phrases in the Bill of Rights. As the English jurist Sir James Fitzjames Stephen wrote in Victorian times, “Words are tools that break in the hand.” We therefore need to define the concepts which lie behind the words of the Bill of Rights.

| Amendment | Bill of Rights Guarantees | First Document Protecting | First American Guarantee | First Constitutional Guarantee |

| Source: Bernard Schwartz, The Roots of the Bill of Rights. Vol. 5 (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1980), 1204. | ||||

| I | Establishment of religion | Rights of the Colonists (Boston) | Same | N.J. Constitution, Art. XIX |

| Free exercise of religion | Md. Act Concerning Religion | Same | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 16 | |

| Free speech | Mass. Body of Liberties, S. 12 | Same | Pa. Declaration of Rights, Art. XII | |

| Free press | Address to Inhabitants of Quebec | Same | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 12 | |

| Assembly | Declaration and Resolves, Continental Congress | Same | Pa. Declaration of Rights, Art. XVI | |

| Petition | Bill of Rights (1689) | Declaration of Rights and Grievances, (1765), S. XIII | Pa. Declaration of Rights, Art. XVI | |

| II | Right to bear arms | Bill of Rights (1689) | Pa. Declaration of Rights, Art. XIII | Same |

| III | Quartering soldiers | N.Y. Charter of Liberties | Same | Del. Declaration of Rights, S. 21 |

| IV | Searches | Rights of the Colonists (Boston) | Same | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 10 |

| Seizures | Magna Carta, c. 39 | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 10 | Same | |

| V | Grand jury indictment | N.Y. Charter of Liberties | Same | N.C. Declaration of Rights, Art. VIII |

| Double jeopardy | Mass. Body of Liberties, S. 42 | Same | N.H. Bill of Rights, Art. XVI | |

| Self-incrimination | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 8 | Same | Same | |

| Due process | Magna Carta, c. 39 | Md. Act for Liberties of the People | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 8 | |

| Just compensation | Mass. Body of Liberties, S. 8 | Same | Vt. Declaration of Rights, Art. II | |

| VI | Speedy trial | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 8 | Same | Same |

| Public trial | West N.J. Concessions, c. XXIII | Same | Pa. Declaration of Rights, Art. IX | |

| Jury trial | Magna Carta, c. 39 | Mass. Body of Liberties, S. 29 | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 8 | |

| Cause and nature of accusation | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 8 | Same | Same | |

| Witnesses | Pa. Charter of Privileges, Art. V | Same | N.J. Constitution, Art. XVI | |

| Counsel | Mass. Body of Liberties, S. 29 | Same | N.J. Constitution, Art. XVI | |

| VII | Jury trial (civil) | Mass. Body of Liberties, S. 29 | Same | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 11 |

| VIII | Bail | Mass. Body of Liberties, S. 18 | Same | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 9 |

| Fines | Pa. Frame of Government, S. XVIII | Same | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 9 | |

| Punishment | Mass. Body of Liberties, S. 43, 46 | Same | Va. Declaration of Rights, S. 9 | |

| IX | Rights retained by people | Va. Convention, proposed amendment 17 | Same | Ninth Amendment |

| X | Reserved Powers | Mass. Declaration of Rights, Art. IV | Same | Same |

Another way to ascertain what the framers of the Bill of Rights intended by their amendments, and what the first Congress and the ratifying State legislatures understood by the amendments’ language, is to consult Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765), and the early Commentaries on the Constitution (1833) and Commentaries on American Law (1826), written, respectively, by Joseph Story and James Kent. As eminent judges during the early decades of the Republic, both Story and Kent were more familiar with the constitutional controversies of the first five presidential administrations than any judge or professor of law near the close of the twentieth century can hope to be.

The comments on the Bill of Rights that follow are based on such sources of information, and also on the books, letters, and journals of political leaders and judges from 1776 to 1840.

It should be noted, moreover, that the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 also sheds light on the ideas and ideals of the generation that drafted the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Passed by the Continental Congress on July 13, 1787, while the Federal Convention was meeting in Philadelphia, the Northwest Ordinance was later affirmed by the first Congress under the new Constitution. Its purpose was to provide a frame of government for the western territories that later became the States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

The Ordinance has been called our first national bill of rights, or “the Magna Charta of American Freedom.” The great American statesman Daniel Webster said he doubted “whether one single law of any lawgiver, ancient or modern, has produced effects of more distinct, marked and lasting character than the Ordinance of 1787.” In addition to protecting many civil liberties that later appeared in the Bill of Rights, the Northwest Ordinance also banned slavery in the Northwest Territory. The wording of the Thirteenth Amendment (1865) providing for the abolition of slavery in the United States was taken directly from the Northwest Ordinance. On the subject of religion, the ordinance provided that “No person, demeaning himself in a peaceable and orderly manner, shall ever be molested on account of his mode of worship or religious sentiments, in said Territory.” The Ordinance also declared as a matter of public policy that because “Religion, morality, and knowledge, [are] necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.”

The First Amendment: Religious Freedom, and Freedom to Speak, Print, Assemble, and Petition

We hear a good deal nowadays about “a wall of separation” between church and state in America. To some people’s surprise, this phrase cannot be found in either the Constitution or the Declaration of Independence. Actually, the phrase occurs in a letter from Thomas Jefferson, as a candidate for office, to an assembly of Baptists in Connecticut.

The first clause of the First Amendment reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” This clause is followed by guarantees of freedom of speech, of publication, of assembly, and of petitioning. These various aspects of liberty were lumped together in the First Amendment for the sake of convenience; Congress had originally intended to assign “establishment of religion” to a separate amendment because the relationships between state and church are considerably different from the civil liberties of speech, publication, assembly, and petitioning.

The purpose of the “Establishment Clause” was two-fold: (1) to prohibit Congress from imposing a national religion upon the people; and (2) to prohibit Congress (and the Federal government generally) from interfering with existing church-state relations in the several States. Thus the “Establishment Clause” is linked directly to the “Free Exercise Clause.” It was designed to promote religious freedom by forbidding Congress to prefer one religious sect over other religious sects. It was also intended, however, to assure each State that its reserved powers included the power to decide for itself, under its own constitution or bill of rights, what kind of relationship it wanted with religious denominations in the State. Hence the importance of the word “respecting”: Congress shall make no law “respecting,” that is, touching or dealing with, the subject of religious establishment.

In effect, this “Establishment Clause” was a compromise between two eminent members of the first Congress—James Madison and Fisher Ames. Representative Ames, from Massachusetts, was a Federalist. In his own State, and also in Connecticut, there still was an established church—the Congregational Church. By 1787–1791, an “established church” was one which was formally recognized by a State government as the publicly preferred form of religion. Such a church was entitled to certain taxes, called tithes, that were collected from the public by the State. Earlier, several other of Britain’s colonies had recognized established churches, but those other establishments had vanished during the Revolution.

Now, if Congress had established a national church—and many countries, in the eighteenth century, had official national churches—probably it would have chosen to establish the Episcopal Church, related to the Church of England. For Episcopalians constituted the most numerous and influential Christian denomination in the United States. Had the Episcopal Church been so established nationally, the Congregational Church would have been disestablished in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Therefore, Fisher Ames and his Massachusetts constituents in 1789 were eager for a constitutional amendment that would not permit Congress to establish any national church or disestablish any State church.

The motive of James Madison for advocating the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment was somewhat different. Madison believed that for the Federal government to establish one church—the Episcopal Church, say—would vex the numerous Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist, Quaker, and other religious denominations. After all, it seemed hard enough to hold the United States together in those first months of the Constitution without stirring up religious controversies. So Madison, who was generally in favor of religious toleration, strongly advocated an Establishment Clause on the ground that it would avert disunity in the Republic.

In short, the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment was not intended as a declaration of governmental hostility toward religion, or even of governmental neutrality in the debate between believers and non-believers. It was simply a device for keeping religious passions out of American politics. The phrase “or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” was meant to keep the Congress from ever meddling in the disputes among religious bodies or interfering with the mode of worship.

During the nineteenth century, at least, State governments would have been free to establish State churches, had they desired to do so. The Establishment Clause restrained only Congress—not State legislatures. But the States were no more interested in establishing a particular church than was Congress, and the two New England States where Congregationalism was established eventually gave up their establishments—Connecticut in 1818, Massachusetts in 1833.

The remainder of the First Amendment is a guarantee of reasonable freedom of speech, publication, assembly, and petition. A key word in this declaration that the Congress must not abridge these freedoms is the article “the”—abridging the freedom of speech and press. For what the Congress had in mind, in 1789, was the civil freedom to which Americans already were accustomed, and which they had inherited from Britain. In effect, the clause means “that freedom of speech and press which prevails today.” In 1789, this meant that Congress was prohibited from engaging in the practice of “prior censorship”—prohibiting a speech or publication without advance approval of an executive official. The courts today give a much broader interpretation to the clause. This does not mean, however, that the First Amendment guarantees any absolute or perfect freedom to shout whatever one wishes, print whatever one likes, assemble in a crowd wherever or whenever it suits a crowd’s fancy, or present a petition to Congress or some other public body in a context of violence. Civil liberty as understood in the Constitution is ordered liberty, not license to indulge every impulse and certainly not license to overthrow the Constitution itself.

As one of the more famous of Supreme Court Justices, Oliver Wendell Holmes, put this matter, “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.” Similarly, statutes that prohibit the publication of obscenities, libels, and calls to violence are generally held by the courts to conform to the First Amendment. For example, public assemblies can be forbidden or dispersed by local authorities when crowds threaten to turn into violent mobs. And even public petitions to the legislative or the executive branch of government must be presented in accordance with certain rules, or else they may be lawfully rejected.

The Constitution recognizes no “absolute” rights. A Justice of the Supreme Court observed years ago that “The Bill of Rights is not a suicide pact.” Instead, the First Amendment is a reaffirmation of certain long-observed civil freedoms, and it is not a guarantee that citizens will go unpunished however outrageous their words, publications, street conduct, or mode of addressing public officials. The original, and in many ways the most important, purpose of freedom of speech and press is that it affords citizens an opportunity to criticize government—favorably and unfavorably—and to hold public officials accountable for their actions. It thus serves to keep the public informed and encourages the free exchange of ideas.

The Second Amendment: The Right to Bear Arms

This amendment consists of a single sentence: “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.”

Although today we tend to think of the “militia” as the armed forces or national guard, the original meaning of the word was “the armed citizenry.” One of the purposes of the Second Amendment was to prevent Congress from disarming the State militias. The phrasing of the Amendment was directly influenced by the American Revolutionary experience. During the initial phases of that conflict, Americans relied on the militia to confront the British regular army. The right of each State to maintain its own militia was thought by the founding generation to be a critical safeguard against “standing armies” and tyrants, both foreign and domestic.

The Second Amendment also affirms an individual’s right to keep and bear arms. Since the Amendment limits only Congress, the States are free to regulate the possession and carrying of weapons in accordance with their own constitutions and bills of rights. “The right of the citizens to keep and bear arms,” observed Justice Joseph Story of the Supreme Court in his Commentaries on the Constitution (1833), “has justly been considered as the palladium of the liberties of the republic, since it offers a strong moral check against the usurpation and arbitrary power of rulers, and will generally, even if these are successful in the first instance, enable the people to resist and triumph over them.” Thus a disarmed population cannot easily resist or overthrow tyrannical government. The right is not absolute, of course, and the Federal courts have upheld Federal laws that limit the sale, possession, and transportation of certain kinds of weapons, such as machine guns and sawed-off shotguns. To what extent Congress can restrict the right is a matter of considerable uncertainty because the Federal courts have not attempted to define its limits.

The Third Amendment: Quartering Troops

Forbidding Congress to station soldiers in private houses without the householders’ permission in time of peace, or without proper authorization in time of war, was bound up with memories of British soldiers who were quartered in American houses during the War of Independence. It is an indication of a desire, in 1789, to protect civilians from military bullying. This is the least-invoked provision of the Bill of Rights, and the Supreme Court has never had occasion to interpret or apply it.

The Fourth Amendment: Search and Seizure

This is a requirement for search warrants when the public authority decides to search individuals or their houses, or to seize their property in connection with some legal action or investigation. In general, any search without a warrant is unreasonable. Under certain conditions, however, no warrant is necessary—as when the search is incidental to a lawful arrest.

Before engaging in a search, the police must appear before a magistrate and, under oath, prove that they have good cause to believe that a search should be made. The warrant must specify the place to be searched and the property to be seized. This requirement is an American version of the old English principle that “Every man’s house is his castle.” In recent decades, courts have extended the protections of this amendment to require warrants for the search and seizure of intangible property, such as conversations recorded through electronic eavesdropping.

The Fifth Amendment: Rights of Persons

Here we have a complex of old rights at law that were intended to protect people from arbitrary treatment by the possessors of power, especially in actions at law. The common law assumes that a person is innocent until he is proven guilty. This amendment reasserts the ancient requirement that if a person is to be tried for a major crime, he must first be indicted by a grand jury. In addition, no person may be tried twice for the same offense. Also, an individual cannot be compelled in criminal cases to testify against himself, “nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”; and the public authorities may not take private property without just compensation to the owner.

The immunity against being compelled to be a witness against one’s self is often invoked in ordinary criminal trials and in trials for subversion or espionage. This right, like others in the Bill of Rights, is not absolute. A person who “takes the Fifth”—that is, refuses to answer questions in a court because his answers might incriminate him—thereby raises “a legitimate presumption” in the court that he has done something for which he might be punished by the law. If offered immunity from prosecution in return for giving testimony, either he must comply or else expect to be jailed, and kept in jail, for contempt of court. And, under certain circumstances, a judge or investigatory body such as a committee of Congress may refuse to accept a witness’s contention that he would place himself in danger of criminal prosecution were he to answer any questions.

The Fifth Amendment’s due process requirement was originally a procedural right that referred to methods of law enforcement. If a person was to be deprived of his life, liberty or property, such a deprivation had to conform to the common law standards of “due process.” The Amendment required a procedure, as Daniel Webster once put it, that “hears before it condemns, proceeds upon inquiries, and renders judgment only after a trial” in which the basic principles of justice have been observed.

The prohibition against taking private property for public use without just compensation is a restriction on the Federal government’s power of eminent domain. Federal courts have adopted a rule of interpretation that the “taking” must be “direct” and that private property owners are not entitled to compensation for indirect loss incidental to the exercise of governmental powers. Thus the courts have frequently held that rent-control measures, limiting the amount of rent which may be charged, are not a “taking,” even though such measures may decrease the value of the property or deprive the owners of rental income. As a general rule, Federal courts have not since 1937 extended the same degree of protection to property rights as they have to other civil rights.

The Sixth Amendment: Rights of the Accused

Here again the Bill of Rights reaffirms venerable protections for persons accused of crimes. The Amendment guarantees jury trial in criminal cases; the right of the accused “to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation”; also the rights to confront witnesses, to obtain witnesses through the arm of the law, and to have lawyers’ help.

These are customs and privileges at law derived from long usage in Britain and America. The recent enlargement of these rights by Federal courts has caused much controversy. The right of assistance of counsel, for example, has been extended backward from the time of trial to the time the defendant is first questioned as a suspect, and forward to the appeals stage of the process. Under the so-called “Miranda” rule, police must read to a suspect his “Miranda” rights before interrogation. Only if a suspect waives his rights may any statement or confession obtained be used against him in a trial. Otherwise the suspect is said to have been denied “assistance of counsel.”

The Sixth Amendment also specifies that criminal trials must be “speedy.” Because of the great backload of cases in our courts, this requirement is sometimes loosely applied today. Yet, as one jurist has put the matter, “Justice delayed is justice denied.”

The Seventh Amendment: Trial by Jury in Civil Cases

This guarantee of jury trial in civil suits at common law “where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars” (a much bigger sum of money in 1789 than now) was included in the Bill of Rights chiefly because several of the States’ ratifying conventions had recommended it. It applies only to Federal cases, of course, and it may be waived. The primary purpose of the Amendment was to preserve the historic line separating the jury, which decides the facts, from the judge, who applies the law. It applies only to suits at common law, meaning “rights and remedies peculiarly legal in their nature.” It does not apply to cases in equity or admiralty law, where juries are not used. In recent years, increasingly large monetary awards to plaintiffs by juries in civil cases have brought the jury system somewhat into disrepute.

The Eighth Amendment: Bail and Cruel and Unusual Punishments

How much bail, fixed by a court as a requirement to assure that a defendant will appear in court at the assigned time, is “excessive”? What punishments are “cruel and unusual”? The monetary sums for bail have changed greatly over two centuries, and criminal punishments have grown less severe. Courts have applied the terms of this amendment differently over the years.

Courts are not required to release an accused person merely because he can supply bail bonds. The court may keep him imprisoned, for example, if the court fears that the accused person would become a danger to the community if released, or would flee the jurisdiction of the court. In such matters, much depends on the nature of the offense, the reputation of the alleged offender, and his ability to pay. Bail of a larger amount than is usually set for a particular crime must be justified by evidence.

As for cruel and unusual punishments, public whipping was not regarded as cruel and unusual in 1789, but it is probably so regarded today. In recent years, the Supreme Court has found that capital punishment is not forbidden by the Eighth Amendment, although the enforcement of capital punishment must be carried out so as not to permit jury discretion or to discriminate against any class of persons. Punishment may be declared cruel and unusual if it is out of all proportion to the offense.

The Ninth Amendment: Rights Retained by the People

Are all the rights to be enjoyed by citizens of the United States enumerated in the first eight amendments and in the Articles of the original Constitution? If so, might not the Federal government, at some future time, ignore a multitude of customs, privileges, and old usages cherished by American men and women, on the ground that these venerable ways were not rights at all? Does a civil right have to be written expressly into the Constitution in order to exist? The Seven Articles and the first eight amendments say nothing, for example, about a right to inherit property, or a right of marriage. Are, then, rights to inheritance and marriage wholly dependent on the will of Congress or the President at any one time?

The Federalists had made such objections to the very idea of a Bill of Rights being added to the Constitution. Indeed, it seemed quite possible to the first Congress under the Constitution that, by singling out and enumerating certain civil liberties, the Seven Articles and the Bill of Rights might seem to disparage or deny certain other prescriptive rights that are important but had not been written into the document.

The Ninth Amendment was designed to quiet the fears of the Anti-Federalists who contended that, under the new Constitution, the Federal government would have the power to trample on the liberties of the people because it would have jurisdiction over any right that was not explicitly protected against Federal abridgment and reserved to the States. They argued in particular that there was an implied exclusion of trial by jury in civil cases because the Constitution made reference to it only in criminal cases.

Written to serve as a general principle of construction, the Ninth Amendment declares that “The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” The reasoning behind the amendment springs from Hamilton’s 83rd and 84th essays in The Federalist. Madison introduced it simply to prevent a perverse application of the ancient legal maxim that a denial of power over a specified right does not imply an affirmative grant of power over an unnamed right.

This amendment is much misunderstood today, and it is sometimes thought to be a source of new rights, such as the “right of privacy,” over which Federal courts may establish jurisdiction. It should be kept in mind, however, that the original purpose of this amendment was to limit the powers of the Federal government, not to expand them.

The Tenth Amendment: Rights Retained by the States

This last amendment in the Bill of Rights was probably the one most eagerly desired by the various State conventions and State legislatures that had demanded the addition of a bill of rights to the Constitution. Throughout the country, the basic uneasiness with the new Constitution was the dread that the Federal government would gradually enlarge its powers and suppress the States’ governments. The Tenth Amendment was designed to lay such fears to rest.

This amendment was simply a declaration that “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” The Federalists maintained that the Framers at Philadelphia had meant from the first that all powers not specifically assigned to the Federal government were reserved to the States or the people of the States.

The amendment declares that powers are reserved “to the States respectively, or to the people,” meaning they are to be left in their original state.

It should be noted that the Tenth Amendment does not say that powers not expressly delegated to the United States are reserved to the States. The authors of the Bill of Rights considered and specifically rejected such a statement. They believed that an amendment limiting the national government to its expressed powers would have seriously weakened it.

During much of our history, the Tenth Amendment was interpreted as a limitation of the delegated powers of Congress. Since 1937, however, the Supreme Court has largely rejected this view, and the Amendment no longer has the same operative meaning or effect that it once had.

Rights Versus Duties

Some Americans seem to fancy that the whole Constitution is a catalog of people’s rights. But actually the major part of the Constitution—the Seven Articles—establishes a framework of national government and only incidentally deals with individuals’ rights.

In any society, duties are often even more important than rights. For example, the duty of obeying good laws is more essential than the right to be exempted from the ordinary operation of the laws. As has been said, every right is married to some duty. Freedom involves individual responsibility.

With that statement in mind, let us look at some of the provisions of the Bill of Rights to see how those rights are joined to certain duties.

If one has a right to freedom of speech, one has a duty to speak decently and honestly, not inciting people to riot or to commit crimes.

If one has a right to freedom of the press (or, in our time, freedom of the “media”), one has the duty to publish the truth, temperately—not abusing this freedom for personal advantage or vengeance.

If one has a right to join other people in a public assembly, one has the duty to tolerate other people’s similar gatherings and not to take the opportunity of converting a crowd into a mob.

If one enjoys an immunity from arbitrary search and seizure, one has the duty of not abusing these rights by unlawfully concealing things forbidden by law.

If one has a right not to be a witness against oneself in a criminal case, one has the duty not to pretend that he would be incriminated if he should testify: that is, to be an honest and candid witness, not taking advantage of the self-incrimination exemption unless otherwise one would really be in danger of successful prosecution.

If one has a right to trial by jury, one ought to be willing to serve on juries when so summoned by a court.

If one is entitled to rights, one has the duty to support the public authority that protects those rights.

For, unless a strong and just government exists, it is vain to talk about one’s rights. Without liberty, order, and justice, sustained by good government, there is no place to which anyone can turn for enforcement of his claims to rights. This is because a “right,” in law, is a claim upon somebody for something. If a man has a right to be paid for a day’s work, for example, he asserts a claim upon his employer; but, if that employer refuses to pay him, the man must turn to a court of law for enforcement of his right. If no court of law exists, the “right” to payment becomes little better than an empty word. The unpaid man might try to take his pay by force, true; but when force rules instead of law, a society falls into anarchy and the world is dominated by the violent and the criminal.

Knowing these hard truths about duties, rights, and social order, the Framers endeavored to give us a Constitution that is more than mere words and slogans. Did they succeed? At the end of two centuries, the Constitution of the United States still functions adequately. Had Americans followed the French example of placing all their trust in a naked declaration of rights, without any supporting constitutional edifice to limit power and the claims of absolute liberty, it may be doubted whether liberty, order, or justice would have prevailed in the succeeding years. There cannot be better proof of the wisdom of the Framers than the endurance of the Constitution.

SUGGESTED READING

- Walter Hartwell Bennett, ed., Letters from the Federal Farmer to the Republican (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1978).

- M. E. Bradford, Original Intentions: On the Making and Ratification of the United States Constitution (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993).

- Neil H. Cogan, ed., The Complete Bill of Rights: The Drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- Patrick T. Conley and John P. Kaminski, The Constitution and the States: The Role of the Original Thirteen in the Framing and Adoption of the Federal Constitution (Madison, Wis.: Madison House, 1988).

- Saul Cornell, Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999).

- Jonathan Elliot, ed., The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution. 5 vols. (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1836–1840). See also James McClellan and M. E. Bradford, eds., Elliot’s Debates in the Several State Conventions … A New, Revised and Enlarged Edition. 7 vols. (Richmond: James River Press, 1989– ). In progress.

- Paul Leicester Ford, ed., Essays on the Constitution of the United States (New York: Burt Franklin, 1970).

- Paul Leicester Ford, Pamphlets on the Constitution of the United States (New York: Da Capo Press, 1968).

- Michael Allen Gillespie and Michael Lienesch, eds., Ratifying the Constitution (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1989).

- Robert A. Goldwin, From Parchment to Power: How James Madison Used the Bill of Rights to Save the Constitution (Washington, D.C.: The AEI Press, 1997).

- Eugene Hickok, ed., The Bill of Rights: Original Meaning and Current Understanding (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991).

- John Kaminski and Gaspare J. Saladino, eds., The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution. 22 vols. (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1976– ). In progress.

- Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner, eds., The Founders’ Constitution. 5 vols. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

- Leonard W. Levy and Dennis J. Mahoney, eds., The Framing and Ratification of the Constitution (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1987).

- Robert Rutland, The Birth of the Bill of Rights (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955).

- Robert Rutland, The Ordeal of the Constitution: The Antifederalists and the Ratification Struggle of 1787–1788 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966).

- Jeffrey St. John, A Child of Fortune: A Correspondent’s Report on the Ratification of the U.S. Constitution and the Battle for a Bill of Rights (Ottawa, Ill.: Jameson Books, 1990).

- Jeffrey St. John, Forge of Union, Anvil of Liberty: A Correspondent’s Report on the First Federal Elections, the First Federal Congress, and the Creation of the Bill of Rights (Ottawa, Ill.: Jameson Books, 1992).

- Bernard Schwartz, ed., The Roots of the Bill of Rights: An Illustrated Sourcebook of American Freedom. 5 vols. (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1980).

- Herbert Storing, ed., The Complete Anti-Federalist. 7 vols. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981).

- John Taylor of Caroline, New Views of the Constitution, ed. by James McClellan (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing Inc., 2000).

- Helen Veit, Kenneth Bowling, and Charlene Bickford, eds., Creating the Bill of Rights: The Documentary Record from the First Federal Congress (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991).